Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

In Fairfax County and across Virginia, a simple breach of contract does not automatically become a tort – even if the breach feels deceptive or harmful. But when a party commits intentional misrepresentation, concealment of material facts, or other false statements that violate duties independent of the contract, the dispute can shift from a contract claim into a tort claim. In practical terms, courts draw a hard line: if the wrongful conduct exists outside the contract’s promises, like fraud in inducing the agreement or professional negligence causing injury, the wronged party may pursue tort remedies (e.g., fraud, negligence) beyond what the contract alone provides. This guide, written from my perspective as a Virginia business litigation attorney, explains how misrepresentations and failures by consultants, contractors, and service providers can extend beyond the scope of contract law. Business owners will find real-world guidance on spotting when a bad deal involves actual deception or professional malpractice – and how to respond strategically. Understanding where contract disputes end and tort liability begins is critical to protecting your company’s rights and maximizing your remedies under Virginia law.

Consultants, Contractors, and Service Providers Whose Failures Go Beyond Contract Obligations. Let’s dive in.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: The Line Between Contract Breach and Tort in Virginia

Chapter 2: Fraudulent Misrepresentation – Turning a Deal into a Deception

Chapter 3: Fraudulent Concealment – Hiding Material Facts as a Form of Fraud

Chapter 4: False Statements and Negligent Misrepresentation – The Gray Areas

Chapter 5: Professional Negligence – When Does a Service Failure Become a Tort?

Chapter 6: Practical Guidance for Business Owners – Navigating Contract vs. Tort Claims

References

Chapter 1: The Line Between Contract Breach and Tort in Virginia

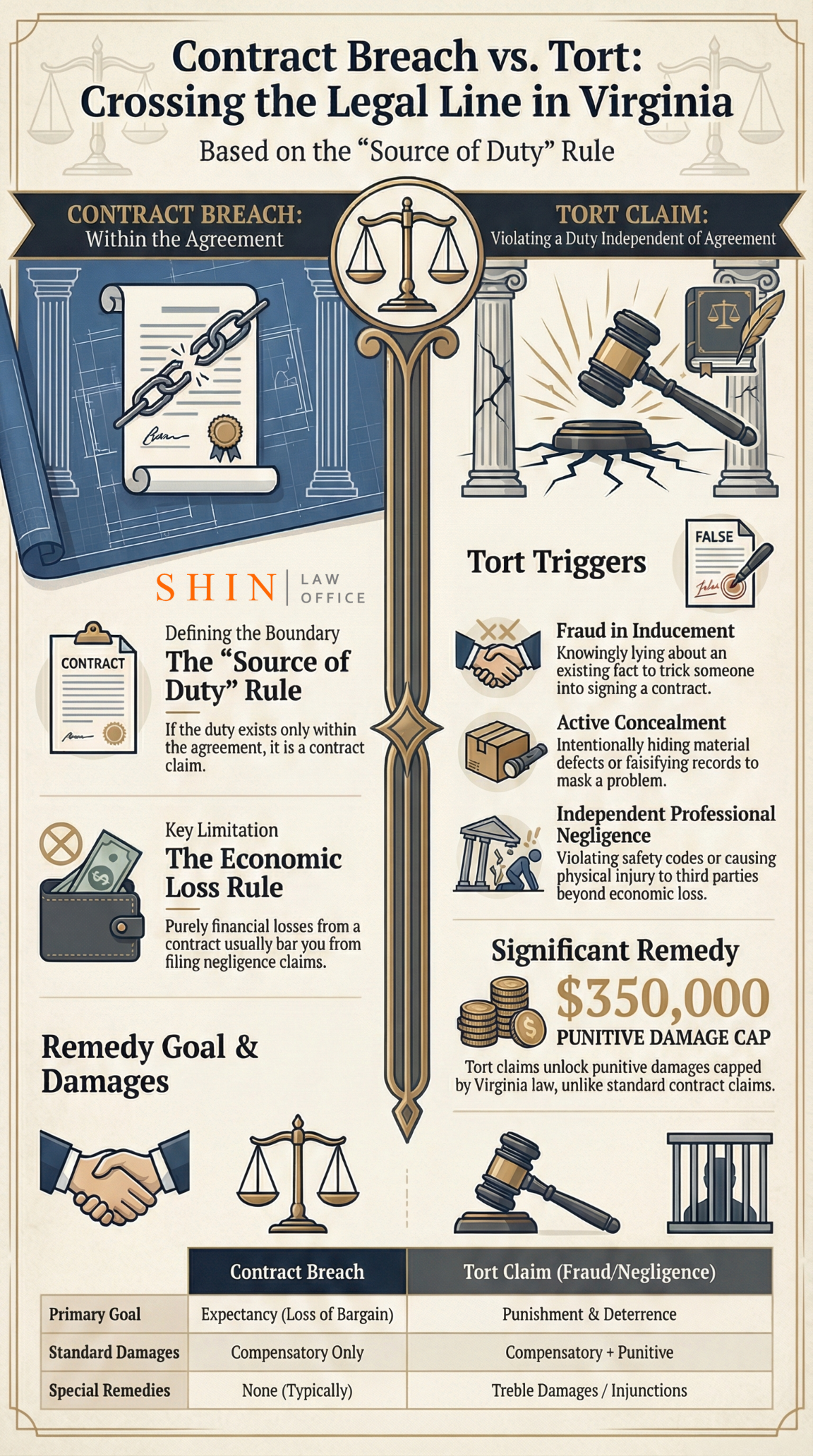

I often explain to clients that not every broken promise is fraud, and not every poor job is a tort. Virginia courts enforce a strict “source of duty” rule, which asks a simple question: Where does the duty come from? If the only duty breached was one created by the contract itself, then the claim “sounds in contract” and must be handled as a breach of contract, with contract remedies. However, if the duty breached exists independently of the contract – such as the common-law duty not to commit fraud or to refrain from causing harm through negligence – then a tort claim may be viable. In other words, deception, fraud, or a violation of public safety duties can elevate a case beyond mere breach of contract.

This distinction matters because tort claims carry powerful remedies that contract claims do not. For example, a fraud or other tort claim may result in punitive damages, statutory treble damages, or injunctive relief, whereas a contract claim typically permits only compensatory damages for expectancy or loss of the bargain. Virginia judges are very careful to prevent litigants from getting tort remedies in what is truly a contract dispute. A common mistake I see is when a plaintiff, frustrated by a breach, tries to “dress up” the claim as a tort by alleging the breach was done in bad faith or with malicious intent. Fairfax County courts (like those in Richmond and elsewhere in Virginia) see through that quickly – “bad faith breach of contract” is not a tort recognized in Virginia. Acting selfishly or unfairly, by itself, does not transform a breach into a fraud or tort.

Virginia’s courts enforce this contract/tort boundary with a couple of key doctrines. One is the source-of-duty rule mentioned above. Another is the economic loss rule, which generally bars tort recovery for purely economic losses arising from a contract. For instance, if a contractor simply fails to deliver on time or does subpar work, and the only loss is the cost to fix it or lost profits, you are typically limited to contract remedies – you can’t turn that into a negligence lawsuit for “economic loss”. However, fraud during contract formation is a classic exception: lying to induce a deal violates the duty not to deceive, even if no contract is ultimately formed. Similarly, a third party’s interference or a professional’s duty of care can be independent of the contract. The big picture is that Virginia draws a hard line: ordinary breaches = contract claims; deception or violations of law = potential tort claims. As we’ll explore, misrepresentations and concealments are prime examples of duties beyond the contract, as is professional negligence that causes injury.

Chapter 2: Fraudulent Misrepresentation – Turning a Deal into a Deception

Misrepresentation – in plain English, lying about a material fact – is the most common way a contract dispute can morph into a tort case for fraud. In Virginia, to prove actual fraud, a plaintiff must show: (1) a false representation of a material fact, (2) made intentionally and knowingly, (3) with intent to mislead, (4) reliance by the plaintiff, and (5) resulting damage. Crucially, that false representation must be about an existing fact (or an omission of fact, as we’ll cover in Chapter 3) – not just a promise of future action. Virginia law is especially strict on this point. If a vendor or service provider simply fails to do what they promised, that is generally a breach of contract, not fraud. I regularly have to tell business owners in Fairfax that “a broken promise isn’t automatically fraud” – otherwise every breach of contract could spawn a fraud claim, which Virginia courts won’t allow. The Supreme Court of Virginia underscored this in the Richmond Metropolitan Authority v. McDevitt Street Bovis case, warning that letting a breach become a fraud without an independent false fact would “obliterate the distinction between contract and tort”.

However, if someone knowingly lied about a fact to get you into the deal, that’s different. For example, suppose a software consulting firm falsely claims that its product meets certain security standards or that it has a certain certification, and you sign the contract relying on that. That pre-contract misrepresentation could be fraud, because the duty not to lie exists outside the contract itself. In Abi-Najm v. Concord Condominium, LLC, buyers alleged the developer misrepresented a material fact about the property’s quality before the contract. The developer argued, “You can’t sue me for fraud because we have a contract,” but the Virginia Supreme Court disagreed: a lie about an existing fact, made to induce the contract, can support an independent fraud claim even if a contract is later signed. The courts basically ask: “Would the conduct be wrongful even if no contract existed?”. Lying to someone to trick them into an agreement is wrongful in itself, contract or no contract.

It’s also worth noting Virginia’s stance on promises. Normally, a promise about future performance can’t be fraud – unless the person making the promise never intended to follow through at the time they made it. This is called promissory fraud and is notoriously hard to prove. The mere fact that a contractor later didn’t deliver is not proof of fraud. You’d have to show, say, internal emails or statements proving they knew from the start they wouldn’t or couldn’t do what they promised. For instance, in Station #2, LLC v. Lynch, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that you must prove the defendant had a present intent not to perform at the time of the promise – simply pointing out that they failed later isn’t enough. In practice, we look for evidence like “smoking gun” documents or admissions that a consultant entered the contract under false pretenses. Absent that, courts in Fairfax will treat it as just a breach (and likely toss any fraud count on demurrer). The bottom line: intentional misrepresentation of present fact is a tort (fraud), but unkept promises are contract breaches unless you can show the lie was there from the very beginning

Chapter 3: Fraudulent Concealment – Hiding Material Facts as a Form of Fraud

Not all deception is an outright lie; sometimes it’s a lie by omission. Concealment of a material fact can also give rise to tort liability in Virginia, but it generally requires more than mere silence – there must be a duty to speak or active hiding of the truth. Virginia courts recognize fraud when a party actively conceals information or prevents the other side from discovering it. For example, if a service provider covers up defects or falsifies records to mask a problem, the law may treat that the same as an affirmative misrepresentation. Fairfax County business disputes often involve scenarios such as a seller omitting known problems or a contractor quietly violating codes without notifying the client. The key is whether the plaintiff reasonably relied on the false impression created by the concealment and could not have easily discovered the truth with ordinary diligence. Courts will ask: Did the victim have a fair opportunity to uncover the issue, or did the defendant effectively prevent them from finding out? If you could have found the truth with minimal investigation, courts may say your reliance was not reasonable, and thus no fraud occurred. But if the other side went out of their way to hide the truth, your reliance on what wasn’t said can be deemed reasonable.

Let’s illustrate with a real-world example from Northern Virginia. I handled a case where a commercial property seller in Loudoun County failed to disclose that the building’s fire alarm system was fundamentally non-compliant and had been flagged by inspectors. Commercial sellers here don’t have as many automatic disclosure duties as in residential sales, so on paper the seller might argue “no duty to volunteer that info.” However, we alleged fraudulent concealment because the seller actively hid the problems – they “conveniently” omitted the fire marshal’s violation notices and even provided some misleading paperwork. We obtained prior inspection reports and emails demonstrating that the seller was aware of the defects and chose not to disclose them. Faced with that evidence, the case quickly shifted from a simple contract dispute (failure to deliver a code-compliant building) into a fraud case. We settled with the seller paying most of the repair costs – a result that would not have been possible without the fraud angle compelling them to the table. The lesson is that in Fairfax and beyond, if you can show the other side intentionally concealed a material problem that you couldn’t have readily discovered, you may have a tort claim for fraud in addition to any contract claims.

On the flip side, courts also remind us that not every hidden problem is actionable fraud. In a notable Loudoun County case (Meng v. Drees Co.), homeowners sued a builder after discovering major structural defects and toxic mold. The jury found the builder negligent (more on that later), but the fraud and Virginia Consumer Protection Act claims were dismissed because the homeowners couldn’t show the builder intentionally misled or concealed facts during the sale. The court basically said: you proved the construction was poor, but you didn’t prove the builder lied or hid info to get you to buy. This underscores that failing to volunteer a problem isn’t fraud unless there was a duty to disclose or a scheme to hide it. For business owners, the practical point is to gather evidence of active concealment – e.g. deleted reports, altered documents, false assurances – if you suspect you were kept in the dark. And conversely, if you’re the one selling or contracting, it’s wise to be forthright about known issues or disclaim them clearly, because cover-ups can expose you to tort liability in a way ordinary contract breaches do not. Courts in Fairfax County will differentiate an honest contract dispute from one tainted by deceitful non-disclosure – only the latter opens the door to punitive damages and fraud remedies.

Chapter 4: False Statements and Negligent Misrepresentation – The Gray Areas

What about situations where false information was given, but not intentionally? Many clients ask if they can sue for negligent misrepresentation – for instance, a consultant provided incorrect data or a contractor misstated something important, but perhaps out of carelessness rather than intent to defraud. Virginia’s approach here is very strict and often misunderstood. Unlike some states, Virginia does not broadly recognize a tort of negligent misrepresentation in commercial contract settings. If the bad information arose from the contract (for example, an erroneous calculation in a report deliverable), courts will usually say that’s a breach of contract issue, not a tort, because the duty to be accurate was part of the contract’s duties. In fact, Virginia courts typically classify these cases as constructive fraud (where a false representation of a fact is made innocently or negligently) or bar them entirely under the economic loss rule. The economic loss doctrine comes up again: if the only loss is financial and stems from disappointed expectations under the contract, you cannot recover in tort for negligence. The idea is that you had the chance to specify duties and remedies in your contract; the court won’t create a tort claim just because you now wish you had more damages or a different cause of action.

Constructive fraud is a narrow avenue Virginia recognizes for false statements made without fraudulent intent. It means a false representation of a material fact was made innocently or negligently, and it harmed someone who reasonably relied on it. The only difference from actual fraud is that you don’t have to prove intent to deceive, but you still have to prove all the other elements (false present fact, reliance, damage) strictly. Many people think this is a “lite” version of fraud that’s easier to establish; in reality, constructive fraud claims usually fail for the same reasons as real fraud. The representation must still be about an existing fact (not a future promise or opinion), and reliance must be reasonable (you can’t ignore obvious red flags or fail to do minimal due diligence). Also, courts will not allow a constructive fraud claim that is basically “you didn’t do what the contract said” – that again falls back to contract law. Virginia judges are quick to dismiss so-called negligent misrepresentation or constructive fraud counts if they “repackage breach-of-contract allegations”. I’ve seen judges in Fairfax sustain demurrers on those claims, explaining that the plaintiff is merely attempting an end run around the economic loss rule or adding a duplicative claim. In short, false statements that are not intentional are tough to litigate as torts in Virginia business cases. Unless the false information violated a duty independent of the contract (for instance, a public safety statute or a fiduciary duty) or caused injury other than economic loss, it will likely be treated as part of the contract dispute.

A practical example: imagine a financial consultant provides a business plan with projections that turn out wildly inaccurate because they negligently used the wrong formula. If your only loss is the money you paid them and the lost expected profits, that’s purely economic loss related to the contract – no tort claim (and indeed Virginia courts have barred accounting malpractice claims in contract scenarios on this basis). If, however, the consultant’s negligence caused a third-party to sue you or led to regulatory fines (a harm beyond the contract’s scope), you might then argue a separate duty was breached (like a professional duty of care to avoid injuring third parties). These situations are highly fact-specific, but the conservative stance of Virginia law means negligence in contract performance is rarely actionable as a tort unless something extra – like public harm or statutory violation – is at play. Business owners should be aware that simply saying “they gave me bad info” isn’t enough – you must fit within one of the narrow exceptions (e.g. constructive fraud with all elements met, or a specific independent duty like a professional license obligation or safety regulation that was breached). Otherwise, your remedy lies in a breach-of-contract claim and any damages you negotiated (which is why robust contracts with representations and warranties are so important).

Chapter 5: Professional Negligence – When Does a Service Failure Become a Tort?

Not every dispute with a consultant, contractor, or service provider will stay in the contract lane. Professional negligence refers to a professional failing to meet the standard of care in their field, potentially causing harm. In Fairfax County, I’ve seen that when a professional’s failure causes only economic loss to the client (and is essentially just poor performance), courts treat it as a contract matter – but if that failure causes injury to persons or damage to other property, it can indeed give rise to tort liability. This is basically Virginia’s economic loss rule applied to professional services. For example, if an engineering firm miscalculates load-bearing and a structure starts cracking, requiring expensive repairs, the owner’s losses are economic (cost of repair, diminished value) – typically a breach of contract or warranty is the remedy. However, if that same miscalculation leads to a catastrophic collapse injuring people or destroying adjacent property, now we’re beyond the contract’s scope: the engineer (and contractor) could be liable in negligence for those injuries or third-party damages. The difference is that safety-related duties and duties to the public kick in – a builder or architect is expected, independent of the contract, not to create a dangerous condition that harms others.

Virginia case law (e.g. the Sensenbrenner decision) has repeatedly held that when a defect or mistake “only undermines a consumer’s economic expectations”, the remedy lies in contract law, not tort. In Sensenbrenner, homeowners sued an architect in tort for a design defect that damaged parts of their own house; the court dismissed the tort claim, calling the loss “disappointed economic expectations” that contract law addresses. By contrast, Virginia courts allow tort claims when the negligence causes personal injury or damage to other property – those are harms that society deems you owe a duty to avoid, contract or no contract. A clear illustration: if a contractor in Arlington builds a retaining wall improperly and it collapses onto a neighbor’s land, wrecking the neighbor’s facility, the neighbor can sue the contractor for negligence even though they had no contract – the contractor breached a general duty not to recklessly damage others’ property. Similarly, if a consultant’s malpractice gives rise to a third-party lawsuit or regulatory violation, that may be beyond what the contract contemplated, exposing the professional to tort liability.

Even within a contract, certain independent legal duties can exist for professionals. For instance, licensed professionals (architects, engineers, doctors, etc.) have duties defined by law or professional standards. In a construction case I handled, we asked: Did the owner rely on the contractor’s specialized expertise (e.g. to design a safe structure)? If yes, that hints the contractor had a professional duty of care beyond just following the contract specs. If the contractor was merely following the client’s plans to the letter, then it’s harder to claim they owed any duty except what was in the contract. Courts also consider statutes and regulations: Virginia’s building code, for example, imposes certain safety obligations on builders for the public’s benefit. A flagrant code violation by a contractor can be seen as negligence per se – effectively a breach of a duty of care owed to others, independent of the contract. In Fairfax County, local building authorities and the Uniform Statewide Building Code create expectations that construction will be done safely and legally. If a contractor or tradesperson violates those codes (e.g., uses unlicensed electricians or ignores fire safety standards) and that results in harm, a court could find they breached a duty to the public, sounding in tort. In one Fairfax case I know of, a negligently installed sprinkler system failed during a fire, causing a much larger blaze. The adjacent businesses sued in tort, and the focus became who had the duty to ensure the system was operational – those duties arose from fire safety regulations and common law, not just the renovation contract.

For business owners, the takeaway is: When a hired professional’s failure causes you pure financial loss related to the contract’s subject, you’re usually looking at a contract claim (perhaps breach of contract or warranty). But if their failure violates an extra-contractual duty – like public safety rules, professional ethics, fiduciary obligations, or causes collateral injury – then you may have a tort claim for negligence or even malpractice. Be prepared to show how the duty breached was “over and above” the contract. Fairfax judges often rely on cases like Ward’s Equipment, Inc. v. New Holland to test this: that case reaffirmed that tort remedies require an independent common-law duty and you cannot simply duplicate contract duties as tort claims. If you can point to a building code, a professional standard of care, or an obligation to the public that was breached, you’re in tort territory. If not, your dispute – no matter how badly you were harmed financially – will likely stay under contract law.

Chapter 6: Practical Guidance for Business Owners – Navigating Contract vs. Tort Claims

Litigation strategy in these situations can significantly impact your outcome, so it’s critical to approach a potential fraud/negligence claim with clear-eyed analysis. Here are some real-world tips I offer to business owners in Fairfax and Northern Virginia:

-

Don’t Cry “Fraud!” Without Facts: Virginia courts demand fraud be pleaded with particularity – the who, what, when, where, and how of the misrepresentation. Alleging fraud or other torts without solid evidence can backfire. Over-pleading (throwing in a fraud count for leverage) may lead to an early dismissal of that count and damage your credibility. I’ve even seen judges warn of sanctions when a fraud claim was obviously baseless. Strategically, you’re often better off with a strong contract case than a weak fraud claim. Only plead tort claims if you truly have the facts to back them up (e.g. documents showing intentional lies or emails revealing conscious wrongdoing).

-

Leverage Tort Claims When Independent Wrongdoing Exists: On the flip side, if you do have evidence of deception or a clear safety lapse, do not hesitate to pursue tort remedies. A well-founded fraud or negligence claim can dramatically increase your settlement leverage and potential recovery. Tort claims may entitle plaintiffs to punitive damages (capped at $350,000 in Virginia for most cases) and, in some cases, statutory attorneys’ fees or treble damages (for example, business conspiracy or certain consumer protection violations). These can pressure a defendant in ways a simple breach of contract cannot. In short, tort claims are powerful when valid – just be sure they are grounded in an independent duty and solid facts.

-

Document Everything and Be Diligent: One common theme across these cases is proof. If you’re the party accusing someone of misrepresentation or concealment, you need a paper trail or witness testimony that nails down the lie or the hidden fact. Save emails, take detailed notes of conversations, and preserve documents. Conversely, if you’re the service provider or seller, use contract clauses to protect yourself – integration clauses, disclaimers of extra representations, and requirements that changes be in writing. Such clauses won’t automatically defeat a fraud claim, but they can make a plaintiff’s reliance less reasonable. Virginia fraud law “rewards diligence and punishes complacency”. That means if you’re the buyer, do your due diligence (courts expect a reasonable investigation if things were accessible); if you’re the seller/contractor, don’t cut corners or hide issues that could later be seen as bad-faith concealment. Being upfront and documenting disclosures can save you from nightmare litigation down the road.

-

Understand Your Remedies and Limitations: If you suspect you’ve been defrauded or harmed by professional negligence, talk to counsel early about the right theory of the case. Sometimes clients fixate on the moral wrongdoing (“They lied! It’s fraud!”) when the smarter legal path is a straightforward breach of contract with clear damages. Other times, clients assume they are limited to the contract, not realizing a tort claim is available for, say, a deliberate misstatement of fact. An experienced attorney can determine whether your case falls on the contract/tort side. Remember, tort claims in Virginia are subject to stricter pleading and often shorter statutes of limitations (for example, fraud is 2 years from discovery, whereas written contracts are 5 years). There may also be insurance implications – many liability insurance policies won’t cover breach of contract, but might cover negligence. All these factors should be weighed.

-

Proactive Measures: Lastly, from a preventive standpoint, consider how you structure your business deals to avoid these disputes. Contracts should explicitly address key representations – who is responsible for verifying what facts, and what happens if those facts prove untrue. For instance, include warranties regarding the condition of goods or the credentials of a consultant, and specify remedies (including liquidated damages) for misrepresentation. You can also include clauses requiring cooperation and disclosure of material information. By spelling out duties, you leave less gray area for “implied” duties that lead to tort fights. Internally, foster a culture of honesty and compliance. I tell business clients: if you have to hide something to close a deal, that’s a red flag. The cost of an uncovered lie – in legal fees, reputation damage, and potential punitive awards – far outweighs the benefit of “getting away with it” short-term.

In sum, Virginia law draws a bright line between contract and tort, but real-life business disputes often test that boundary. As a business owner in Fairfax County or elsewhere in Northern Virginia, you should approach any serious dispute by asking: Did the other party simply break a promise, or did they engage in deceit or dangerous conduct? If it’s the former, prepare for a contract case and focus on enforcing the agreement. If it’s the latter, you may have a tort on your hands – and with it, a chance for broader recovery, but also a heavier burden of proof. Understanding this distinction – and acting on it early – will help you protect your interests effectively when things go wrong. As I often remind clients, not every wrong constitutes a tort, but when a dispute involves lies, concealment, or a breach of professional duty, tort law can provide leverage that contract law cannot. Knowing the difference is half the battle in business litigation.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

Shin, A. I. (n.d.-a). Business Fraud and Tortious Interference Litigation in Fairfax County. Shin Law Office Blog. Retrieved from https://shinlawoffice.com/business-fraud-and-tortious-interference-litigation-in-fairfax-county/

Shin, A. I. (n.d.-b). Business Torts and Contract Litigation in Richmond, Virginia. Shin Law Office Blog. Retrieved from https://shinlawoffice.com/business-torts-and-contract-litigation-in-richmond-virginia/

Shin, A. I. (n.d.-c). What Counts as Business Fraud in Virginia and Loudoun County. Shin Law Office Blog. Retrieved from https://shinlawoffice.com/what-counts-as-business-fraud-in-virginia-and-loudoun-county/

Shin, A. I. (n.d.-d). Commercial Construction Lawsuits in Northern Virginia. Shin Law Office Blog. Retrieved from https://shinlawoffice.com/commercial-construction-lawsuits-in-northern-virginia/

Sensenbrenner v. Rust, Orling & Neale, P.E., 236 Va. 419, 374 S.E.2d 55 (1988). (Economic loss rule in construction defect context – no tort for “disappointed expectations” of contract).

Station #2, LLC v. Lynch, 280 Va. 166, 695 S.E.2d 537 (2010). (Promissory fraud requires present intent not to perform).

Abi-Najm v. Concord Condominium, LLC, 280 Va. 350, 699 S.E.2d 483 (2010). (Pre-contract misrepresentations of present fact can support fraud claim).

Richmond Metro. Auth. v. McDevitt Street Bovis, Inc., 256 Va. 553, 507 S.E.2d 344 (1998). (Cannot convert contract breach to fraud unless misrepresentation of present fact independent of contract).

Ward’s Equipment, Inc. v. New Holland N. Am., Inc., 254 Va. 379, 493 S.E.2d 516 (1997). (Tort claim only if breaching duty not imposed by the contract).

Virginia Code § 8.01-38.1 (2014). Punitive damages cap of $350,000 in most civil actions.