BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)

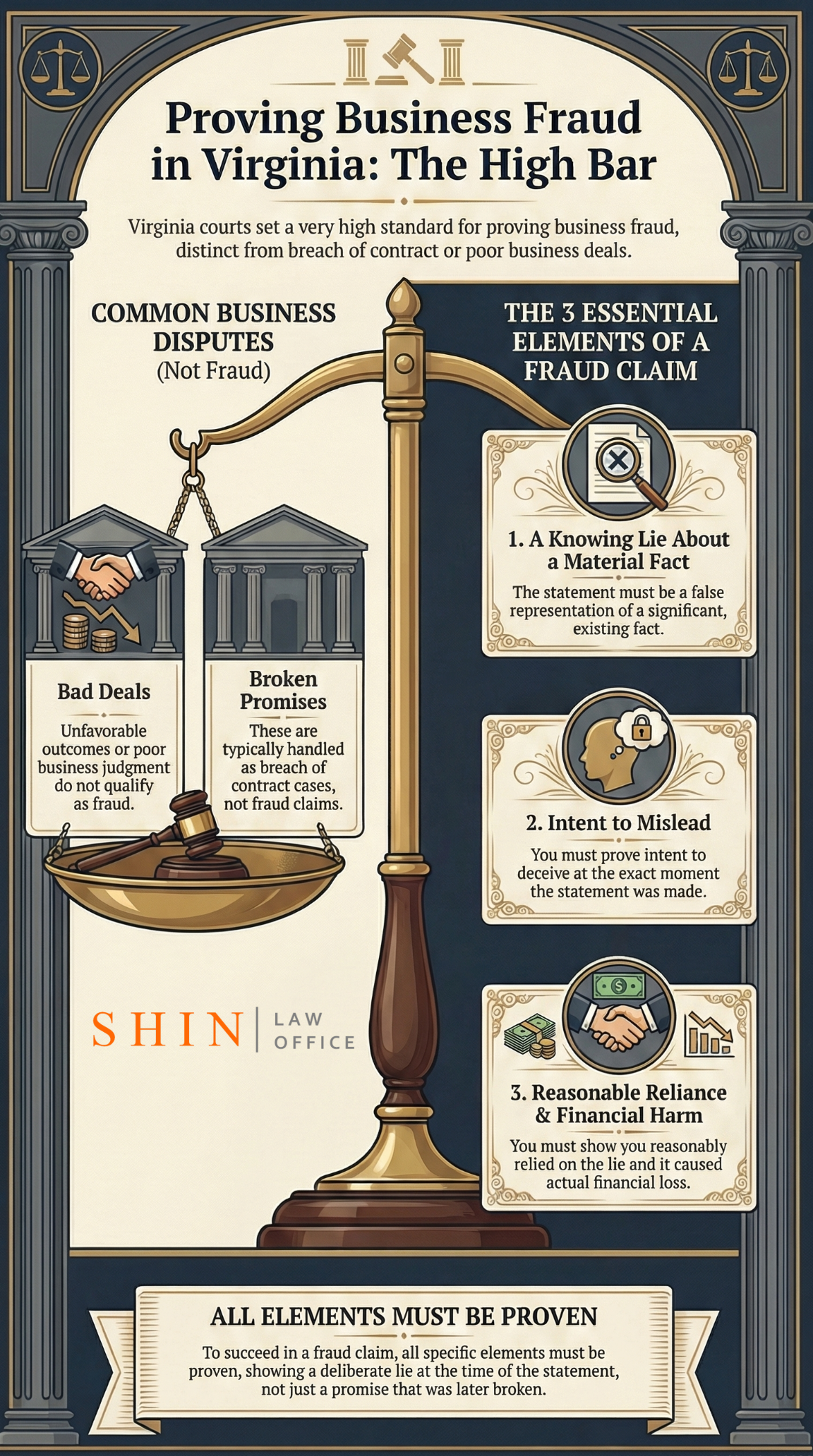

Business fraud in Virginia is not a catch-all for bad deals, broken promises, or business disappointment. In Loudoun County and across the Commonwealth, courts apply some of the strictest fraud standards in the country, and only intentional deception — not hindsight or frustration — qualifies as fraud. To prevail on a business fraud claim under Virginia law, you generally must show that someone knowingly misrepresented a material fact at the exact moment the statement was made, that you reasonably relied on that misrepresentation, and that it directly caused measurable financial harm. Claims that blur fraud with breach of contract, rely on later conduct, or ignore Virginia’s rigorous requirements often fail at the earliest stages of litigation. Understanding these legal boundaries early empowers business owners and litigants to pursue only claims the courts will enforce and to avoid wasted time, expense, and credibility-damaging missteps. Shin Law Office

If you are asking questions like these, this article is written for you:

• What legally qualifies as business fraud in Virginia and Loudoun County?

• How is business fraud different from a breach of contract under Virginia law?

• What proof do I need to show someone intentionally deceived me?

• Can I bring fraud and breach of contract claims at the same time?

• What happens to a fraud claim if it’s dismissed early by the court?

This guide explains how Virginia courts evaluate fraud claims, why many fraud theories collapse before discovery, and what evidence matters most when serious deception is alleged.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Why Business Fraud in Virginia Is So Often Misunderstood

- Chapter 2: How Virginia Courts Actually Define Civil Business Fraud

- Chapter 3: What Makes Fraud Different From a Breach of Contract

- Chapter 4: How Intent and Timing Control the Outcome of Fraud Claims

- Chapter 5: What Reasonable Reliance Really Means for Business Owners

- Chapter 6: Understanding Constructive Fraud and Negligent Misrepresentation

- Chapter 7: Why Most Virginia Fraud Claims Are Dismissed Early

- Chapter 8: Criminal Business Fraud Charges Prosecuted in Loudoun County

- Chapter 9: How Civil and Criminal Fraud Cases Intersect

- Chapter 10: What Loudoun County Business Owners Should Do When Fraud Is Suspected

Chapter 1

Why Business Fraud in Virginia Is So Often Misunderstood

I regularly meet business owners who believe they have been defrauded, only to learn that Virginia law sees the situation very differently. This disconnect is not accidental. Virginia intentionally applies one of the strictest fraud standards in the country, and that reality surprises even sophisticated executives.

In Virginia, business fraud is not a single statute, and it is not a catch-all remedy for unfair conduct. Instead, it is a tightly controlled legal doctrine designed to punish intentional deception, not failed business deals, broken promises, or bad outcomes. That distinction is critical for anyone operating in Loudoun County or anywhere else in the Commonwealth.

One of the most common misconceptions I encounter is the belief that fraud simply means someone did not do what they promised. Virginia courts reject that idea outright. A party can breach a contract, act irresponsibly, or even behave unfairly without committing fraud. Fraud requires proof that the defendant lied about an existing fact with the intent to mislead at the moment the statement was made.

This is where many claims fail before they ever reach trial.

Virginia courts are deeply concerned about preventing ordinary business disputes from being inflated into fraud cases. That concern shows up in two ways. First, fraud must be proven by clear and convincing evidence, a higher burden than most civil claims. Second, courts closely scrutinize fraud pleadings at the earliest stages of litigation.

If a complaint does not allege exactly who said what, when it was said, why it was false, and how the plaintiff relied on it, the case is vulnerable to immediate dismissal.

Another reason business fraud is misunderstood is that Virginia law draws a sharp line between statements of fact and statements of opinion or future intent. Promises about future performance are not fraud unless the plaintiff can prove that the promise was made with a present intent not to perform. That is a very high evidentiary bar.

From a practical standpoint, this means that fraud cases often turn on documents, internal communications, and circumstantial evidence showing what the defendant knew at the time. Hindsight is not enough. Courts do not allow parties to infer fraud simply because a deal went sideways.

In Loudoun County, where commercial activity continues to expand across technology, government contracting, real estate, and professional services, these distinctions matter even more. Businesses routinely engage in complex negotiations that involve projections, assumptions, and risk. Virginia law expects business actors to exercise diligence, ask questions, and protect themselves contractually.

That expectation also affects the concept of reliance. Virginia does not protect blind reliance. If a party had the ability to verify information or investigate a claim and failed to do so, courts may find their reliance unreasonable. This is especially true in transactions between experienced commercial parties.

The result is a legal environment where fraud claims are powerful but rare. When proven, they can support rescission, compensatory damages, and in some cases punitive damages. But when improperly pled, they often collapse quickly.

Understanding these realities at the outset allows business owners to make informed decisions. It also prevents wasted resources pursuing claims that Virginia law simply will not support.

Chapter 2

How Virginia Courts Actually Define Civil Business Fraud

Virginia courts do not approach fraud casually. They treat it as an extraordinary claim that must be proven element by element, without shortcuts or assumptions. When I evaluate a potential fraud case, the first question I ask is not whether the conduct feels deceptive, but whether it satisfies Virginia’s legal framework for civil fraud.

To establish actual fraud in a Virginia civil court, a plaintiff must prove six specific elements by clear and convincing evidence. Missing even one is fatal to the claim. Courts do not balance equities or fill in gaps with speculation.

The first requirement is a false representation. There must be an objectively false statement, not silence, not exaggeration, and not a broken promise standing alone. The misrepresentation must be concrete and identifiable.

Second, the statement must concern a present and material fact. Materiality matters because courts will not entertain fraud claims based on trivial inaccuracies. The fact must be significant enough that a reasonable person would consider it important when deciding whether to proceed.

Third, the defendant must have known the statement was false or made it recklessly. Negligence is not enough for actual fraud. This is where internal emails, financial records, and prior representations often become decisive evidence.

Fourth, the statement must have been made with intent to mislead. Virginia courts require proof that the misrepresentation was designed to induce action. Accidental misinformation does not qualify.

Fifth, the plaintiff must have reasonably relied on the statement. This is often where sophisticated businesses run into trouble. Courts expect parties to exercise ordinary care and use available means to verify claims.

Finally, the plaintiff must show resulting damages. There must be a direct causal link between the reliance and actual financial harm.

These elements are applied rigorously by courts, including those serving Loudoun County. Fraud claims that blur these requirements are routinely dismissed before discovery ever begins.

In the next chapter, I explain why Virginia law is especially hostile to attempts to convert breach of contract claims into fraud actions, and how courts enforce that boundary with precision.

Chapter 3

What Makes Fraud Different From a Breach of Contract Under Virginia Law

One of the most important distinctions I explain to business owners in Loudoun County is this: not every broken promise is fraud. In fact, Virginia courts are explicit that fraud and breach of contract serve very different legal purposes, and attempts to blur that line are routinely rejected.

This principle is so central to Virginia jurisprudence that entire fraud cases rise or fall on it.

Under Virginia law, a breach of contract occurs when a party fails to perform a contractual obligation. Fraud, by contrast, focuses on conduct that occurs before or at the time the contract is formed. The difference is not semantic. It is structural, and courts enforce it aggressively.

Why Virginia Law Separates Fraud From Contract Claims

Virginia follows what courts often refer to as the “source of duty” rule. If the duty allegedly violated arises solely from the contract itself, the claim sounds in contract, not tort. Fraud requires the violation of a duty independent of the contract.

This doctrine prevents parties from recharacterizing ordinary contract disputes as fraud simply to obtain leverage, punitive damages, or attorney’s fees.

The Supreme Court of Virginia made this clear in Richmond Metropolitan Authority v. McDevitt Street Bovis, Inc., where the Court held that a plaintiff cannot convert a breach of contract into a fraud claim unless the misrepresentation concerns a present fact and not a contractual promise. The Court emphasized that allowing otherwise would “obliterate the distinction between contract and tort.”

That reasoning remains controlling today.

What Virginia Courts Say About Fraud Based on Promises

A recurring issue in business litigation is whether a promise about future performance can constitute fraud. The answer in Virginia is almost always no, unless one very specific condition is met.

Virginia courts recognize an exception when a promise is made with a present intent not to perform. This is sometimes called promissory fraud, but it is notoriously difficult to prove.

In Station #2, LLC v. Lynch, the Supreme Court of Virginia reaffirmed that mere failure to perform does not establish fraud. The plaintiff must prove that, at the time the promise was made, the defendant already intended not to perform. Evidence of later nonperformance, standing alone, is insufficient.

This rule exists because business transactions inherently involve risk. Deals fail. Markets change. Virginia law does not punish bad outcomes. It punishes intentional deception.

How Courts Apply This Rule in Real Business Disputes

In practice, this distinction is most often enforced at the pleading stage. Courts require fraud claims to be pled with particularity under Virginia law, identifying the precise misrepresentation, who made it, when it was made, and why it was false when made.

If a complaint alleges that a party promised to do something and later failed to do it, courts will usually dismiss the fraud count and allow only the breach of contract claim to proceed.

The Supreme Court of Virginia underscored this approach in Abi-Najm v. Concord Condominium, LLC. While the Court allowed certain fraud claims to proceed, it did so only because the plaintiffs alleged misrepresentations of existing fact that were independent of the contractual obligations. The Court reaffirmed that promises tied directly to contract performance cannot support fraud without proof of contemporaneous intent to deceive.

This framework is applied consistently in circuit courts across the Commonwealth, including those serving Loudoun County.

Why This Matters So Much in Loudoun County Business Litigation

Loudoun County sees a high volume of disputes involving technology companies, government contractors, real estate developers, and professional services firms. These cases often involve sophisticated contracts with detailed representations, warranties, and integration clauses.

Virginia courts expect those contracts to govern the parties’ rights and remedies.

When businesses attempt to bypass those negotiated terms by alleging fraud without independent misrepresentations of present fact, courts intervene quickly. Judges understand that allowing routine contract disputes to proceed as fraud would destabilize commercial relationships and discourage efficient contracting.

The Practical Risk of Over Pleading Fraud

Over pleading fraud can backfire. Alleging fraud without sufficient factual support can undermine credibility, trigger early dismissal, and even expose a party to sanctions in extreme cases.

Strategically, it is often more effective to pursue a well supported breach of contract claim than to dilute the case with an unsustainable fraud theory.

Understanding this boundary allows businesses to litigate smarter, not louder.

In the next chapter, I explain why intent and timing control fraud outcomes in Virginia and how courts analyze what a defendant knew and when they knew it.

Chapter 4

How Intent and Timing Control the Outcome of Fraud Claims in Virginia

If there is one concept that determines whether a business fraud claim in Virginia survives or collapses, it is intent at the moment the statement was made. I cannot overstate how decisive this requirement is. In my experience, most fraud cases do not fail because the plaintiff cannot show harm. They fail because they cannot prove what the defendant knew and intended at a specific point in time.

Virginia courts are unwavering on this issue. Fraud is judged at the moment of representation, not in hindsight. The law asks a narrow question: Did the defendant knowingly misrepresent a present fact with the intent to mislead when the statement was made.

Everything else flows from that inquiry.

Why Timing Matters More Than Outcome

Business disputes often arise after deals fall apart. Revenues miss projections. Deliverables come late. Relationships deteriorate. From the injured party’s perspective, the failure feels deceptive. But Virginia law does not infer fraud from failure.

The Supreme Court of Virginia has repeatedly emphasized that subsequent nonperformance does not prove fraudulent intent. In Patrick v. Summers, the Court explained that intent must exist at the time of the alleged misrepresentation. Evidence that a party later changed course or failed to perform is legally insufficient by itself.

This is why fraud claims that rely heavily on “what happened later” are vulnerable from the start.

How Virginia Courts Evaluate Intent

Because intent is rarely admitted outright, courts allow it to be proven through circumstantial evidence. But that evidence must still point backward to the moment the statement was made.

Courts look for indicators such as internal documents that contradict public representations, contemporaneous financial records showing impossibility of performance, or proof that the defendant lacked authority to do what they claimed they could do.

In Boykin v. Hermitage Realty, the Supreme Court of Virginia allowed a fraud claim to proceed where evidence showed the defendant made representations about zoning approvals that were already known to be false at the time. The key was not that the project failed, but that the falsity existed when the statement was made.

This is a recurring pattern in viable fraud cases. The deception is baked in from the start.

Why Promises Are Treated With Extreme Skepticism

Virginia courts are especially cautious with fraud claims based on promises of future action. The law recognizes that business negotiations involve estimates, expectations, and risk allocation. Treating unmet expectations as fraud would paralyze commerce.

That is why the Supreme Court of Virginia in Colonial Ford Truck Sales, Inc. v. Schneider reaffirmed that promises about future conduct are not actionable unless the plaintiff can prove the promisor had a present intention not to perform.

This is a demanding standard. Courts require specific factual allegations showing that the promise was false when made, not merely that it went unfulfilled.

How Intent Is Tested at the Pleading Stage

Virginia courts do not wait for trial to test intent. Fraud claims are scrutinized at the demurrer stage, where judges examine whether the complaint plausibly alleges fraudulent intent with sufficient detail.

Conclusory statements that a defendant “never intended to perform” are not enough. Courts require facts showing how that intent existed at the outset.

In circuit courts serving Loudoun County, judges routinely dismiss fraud claims that lack this temporal precision. This is especially true in cases involving sophisticated commercial parties who negotiated detailed contracts.

The Strategic Importance of Early Evidence Preservation

Because intent turns on what existed at the time of representation, early evidence preservation is critical. Emails, drafts, internal memoranda, financial projections, and approval records often determine whether intent can be proven at all.

Delay can destroy a fraud case before it begins.

From a defense perspective, this same reality makes early motion practice effective. If the complaint cannot plausibly allege contemporaneous intent to deceive, dismissal is not just possible, it is likely.

Why Intent Protects Legitimate Business Risk Taking

Virginia’s strict intent requirement serves an important policy function. It protects businesses from being punished for taking calculated risks that do not pan out. Innovation requires uncertainty. Contracts exist to allocate that risk.

Fraud law steps in only when one party crosses the line from risk taking into deception.

Understanding how intent and timing operate allows businesses to assess claims realistically. It also prevents costly litigation driven by frustration rather than law.

In the next chapter, I explain how reasonable reliance operates as a separate gatekeeper in Virginia fraud cases, and why courts often find that sophisticated businesses relied at their own peril.

Chapter 5

What Reasonable Reliance Really Means for Business Owners Under Virginia Law

Even when a business owner can identify a false statement and even when that statement appears intentional, many fraud claims in Virginia still fail for one simple reason: reliance was not reasonable. This element is not a technicality. It is a central gatekeeper in Virginia fraud law, and courts apply it rigorously.

I often tell clients that Virginia does not protect blind trust in business transactions. The law expects parties, especially sophisticated ones, to protect themselves.

Why Reasonable Reliance Is a Separate and Powerful Barrier

To prove fraud in Virginia, a plaintiff must show not only that a misrepresentation occurred, but that they reasonably relied on it. That word reasonably does heavy lifting.

Virginia courts ask whether the plaintiff exercised ordinary care under the circumstances. If the truth was available through minimal diligence, courts may find reliance unreasonable as a matter of law.

This principle is not new. In Metrocall of Delaware, Inc. v. Continental Cellular Corp., the Supreme Court of Virginia held that reliance is unreasonable when a party has access to information that would have revealed the truth and fails to investigate. The Court emphasized that fraud law does not exist to rescue parties from their own lack of diligence.

How Sophistication Changes the Reliance Analysis

Virginia courts explicitly consider the sophistication of the parties involved. A consumer transaction is treated very differently from a commercial deal between experienced business entities.

When businesses negotiate contracts, courts assume they understand the risks, have access to advisors, and can request documentation or conduct due diligence. As a result, courts hold them to a higher standard.

In Horner v. Ahern, the Supreme Court of Virginia rejected a fraud claim where the plaintiff relied on representations that could have been verified through readily available records. The Court made clear that a party cannot ignore obvious warning signs and later claim fraud.

This reasoning is applied consistently in business litigation across the Commonwealth, including cases arising in Loudoun County, where commercial parties are often well represented and contract terms are heavily negotiated.

What Kinds of Reliance Courts Commonly Reject

Virginia courts routinely find reliance unreasonable in several recurring scenarios.

If a contract includes clear disclaimers, integration clauses, or representations limiting reliance to written terms, courts are skeptical of claims based on prior oral statements. While such clauses do not automatically bar fraud claims, they significantly weaken reliance arguments.

Courts also reject reliance where the plaintiff could inspect records, request financials, or verify authority but chose not to do so. Fraud law does not reward willful ignorance.

In Foremost Guaranty Corp. v. Meritor Savings Bank, the Court emphasized that when a party fails to investigate despite having the means to do so, reliance may be deemed unreasonable as a matter of law.

When Reliance Can Still Be Reasonable

This does not mean reliance is never reasonable in commercial settings. Courts recognize fraud where a defendant actively conceals information, falsifies records, or prevents verification.

For example, reliance may be reasonable where a party provides forged documents, lies about existing approvals, or misrepresents facts uniquely within their control. In those cases, diligence would not uncover the truth.

The key distinction is whether the plaintiff could have discovered the truth through the exercise of ordinary care. If the answer is yes, reliance becomes difficult to defend.

Why Reliance Is Often Decided Early in Litigation

Because reliance is heavily fact-dependent but also tied to objective standards, Virginia courts frequently resolve this issue at the demurrer or summary judgment stage.

Judges are not hesitant to rule that reliance was unreasonable when pleadings or undisputed facts show that verification was possible. This makes reliance one of the most common failure points for fraud claims.

From a strategic perspective, plaintiffs must plead reliance with specificity and realism. Defendants, on the other hand, often focus early motions on showing that the plaintiff assumed a risk the law does not protect.

The Practical Lesson for Virginia Businesses

Fraud law in Virginia rewards diligence and punishes complacency. Businesses that document representations, verify key facts, and structure contracts carefully are better protected both offensively and defensively.

Understanding how reasonable reliance operates allows business owners to assess claims honestly before litigation begins.

In the next chapter, I explain how constructive fraud and negligent misrepresentation fit into Virginia law and why they are often misunderstood as easier alternatives to actual fraud.

Chapter 6

Understanding Constructive Fraud and Negligent Misrepresentation in Virginia

After learning how demanding actual fraud is under Virginia law, many business owners ask me whether there is an easier alternative. Constructive fraud and negligent misrepresentation are often raised as possibilities. While these doctrines do exist in Virginia, they are frequently misunderstood and just as frequently misapplied.

Constructive fraud is not a fallback claim for weak fraud cases. It is a distinct legal theory with its own limitations, and it does not eliminate the core requirements that make fraud difficult to prove in the first place.

What Constructive Fraud Actually Means in Virginia

Constructive fraud occurs when a false representation of a material fact is made innocently or negligently, rather than intentionally, and causes damage to the party who reasonably relied on it. The critical difference from actual fraud is the absence of intent to deceive.

Virginia courts recognize constructive fraud because harm can still occur even when a defendant did not set out to mislead. But the absence of intent does not relax the other elements of the claim.

A plaintiff must still prove a false representation of a present material fact, reasonable reliance, and resulting damages. The evidentiary burden is slightly lower than actual fraud, but it remains substantial.

Why Constructive Fraud Is Still Hard to Prove

Many plaintiffs assume constructive fraud is easier because intent is not required. In reality, most constructive fraud claims fail for the same reasons actual fraud claims fail.

The representation must still concern an existing fact, not a future promise. Courts will not allow constructive fraud claims based on predictions, estimates, or contractual expectations.

Reliance must still be reasonable. If the plaintiff could verify the information or investigate the truth, constructive fraud fails just as actual fraud does.

Virginia courts have been clear that constructive fraud does not excuse a lack of diligence.

How Virginia Courts Treat Negligent Misrepresentation

Unlike some states, Virginia does not broadly recognize negligent misrepresentation as an independent tort in commercial settings. Instead, negligent misrepresentation claims are often analyzed through the lens of constructive fraud or barred entirely by the economic loss rule.

Virginia courts are cautious about allowing negligence-based claims to intrude into contract law. If the alleged misrepresentation arises from contractual duties rather than an independent duty imposed by law, courts will usually dismiss the claim.

This limitation is especially important in business litigation, where most representations are tied directly to negotiated agreements.

The Economic Loss Rule and Its Impact

The economic loss rule plays a central role in restricting constructive fraud and negligent misrepresentation claims. The rule prevents recovery in tort for purely economic losses that arise from contractual relationships.

Virginia courts use this rule to preserve the boundary between contract and tort. If the only damages claimed are economic losses governed by the contract, and there is no independent duty, tort claims are often barred.

This principle applies consistently in circuit courts across the Commonwealth, including those serving Loudoun County.

When Constructive Fraud Can Still Apply

Constructive fraud may be viable when a party negligently misrepresents an existing fact that is outside the contract or uniquely within their knowledge. Examples include misstatements about regulatory approvals, ownership interests, or existing financial conditions that induce a transaction.

Even then, courts scrutinize these claims. The plaintiff must show that the misrepresentation was material, that reliance was justified, and that damages flowed directly from that reliance.

Strategic Risks of Overusing Constructive Fraud

From a litigation strategy standpoint, constructive fraud should not be treated as a safety net. Adding unsupported constructive fraud claims can weaken a case by distracting from stronger contract theories.

Judges are quick to dismiss constructive fraud claims that merely repackage breach-of-contract allegations. When that happens, credibility suffers.

The Practical Reality for Virginia Businesses

Constructive fraud is not a shortcut around Virginia’s strict fraud standards. It exists to address specific situations where negligence causes real harm, not to rescue disappointed expectations.

Business owners are better served by understanding where this doctrine applies and where it does not.

In the next chapter, I explain why most Virginia fraud claims are dismissed early, and how procedural rules and pleading standards often determine the outcome before discovery even begins.

Chapter 7

Why Most Virginia Business Fraud Claims Are Dismissed Early

By the time a business fraud case reaches my desk, the most critical question is often not whether fraud occurred, but whether the claim will survive the first procedural challenge. In Virginia, most fraud claims never reach discovery. They are dismissed early, sometimes within weeks, for failing to meet strict pleading and procedural standards.

This reality surprises many business owners. They assume courts want to hear the full story before ruling. Virginia courts take a different approach. Fraud is treated as an extraordinary allegation, and extraordinary allegations must be pled with exceptional precision.

Why Virginia Courts Scrutinize Fraud at the Outset

Virginia courts are deeply concerned about the misuse of fraud claims. Fraud allegations carry reputational harm, expanded discovery, and the potential for punitive damages. To prevent abuse, courts act as gatekeepers.

At the earliest stage of litigation, typically through a demurrer, judges test whether the complaint alleges legally sufficient fraud, not whether the plaintiff might eventually uncover evidence.

If the pleading does not satisfy Virginia’s exacting standards, the case ends before it begins.

The Requirement to Plead Fraud With Particularity

Unlike ordinary civil claims, fraud must be pled with particularity. This means a plaintiff must allege the specific who, what, when, where, and how of the alleged misrepresentation.

General accusations that a defendant misled or deceived are not enough. Courts require identification of the exact statement, who made it, when it was made, why it was false at the time, and how the plaintiff relied on it.

Virginia courts consistently hold that vague or conclusory allegations cannot support a fraud claim.

Why Conclusory Allegations Fail

One of the most common reasons fraud claims are dismissed is reliance on conclusory language. Phrases such as “the defendant knew,” “the defendant intended,” or “the defendant misrepresented” without factual support are insufficient.

Courts do not infer intent, knowledge, or falsity simply because a deal went badly. The complaint must allege facts showing that the representation was false when made and that the defendant knew it.

When pleadings rely on assumptions or hindsight, dismissal is likely.

How Contract Language Undermines Fraud Claims

Contractual provisions often play a decisive role at the pleading stage. Courts frequently cite integration clauses, reliance disclaimers, and representations limited to written terms in dismissing fraud claims.

While such clauses do not automatically bar fraud, they severely weaken allegations of reasonable reliance. Courts ask a straightforward question: why did the plaintiff rely on an alleged oral statement when the contract says otherwise?

In commercial disputes, this question is often fatal.

Why Courts Dismiss Fraud to Preserve Contract Law

Virginia courts are protective of contract law. They recognize that parties allocate risk through negotiation, warranties, and remedies. Allowing weak fraud claims to proceed would undermine that framework.

As a result, courts dismiss fraud claims that merely restate breach-of-contract allegations in different language. This happens regularly in cases involving complex commercial agreements, including those litigated in Loudoun County.

Judges understand that if fraud claims were allowed whenever a contract was breached, every business dispute would become a tort case.

Procedural Discipline as a Strategic Advantage

For defendants, early dismissal is often the primary objective. Challenging fraud claims through demurrer narrows the case, reduces discovery exposure, and forces plaintiffs to confront the weaknesses in their theory.

For plaintiffs, this reality means fraud must be evaluated ruthlessly before filing. Unsupported fraud claims waste time, increase costs, and erode credibility with the court.

The Practical Lesson for Business Owners

Virginia fraud litigation rewards precision and punishes overreach. Businesses that approach fraud claims emotionally rather than legally often find themselves dismissed early and decisively.

Understanding why courts act quickly helps business owners make better decisions about when fraud claims are appropriate and when they are not.

In the next chapter, I explain the criminal fraud statutes most commonly prosecuted in business cases, how they differ from civil fraud, and what Loudoun County businesses need to know when criminal exposure arises.

Chapter 8

What Criminal Business Fraud Charges Look Like in Virginia and Loudoun County

Up to this point, I have focused on civil fraud, where private parties seek financial recovery. Criminal business fraud is fundamentally different. When fraud crosses into criminal territory in Virginia, the objective is no longer compensation. It is punishment, deterrence, and public accountability.

For business owners in Loudoun County, understanding this distinction is critical because conduct that begins as a civil dispute can evolve into a criminal investigation with serious consequences.

Why Virginia Does Not Have a Single Criminal Fraud Statute

Virginia does not define business fraud through a catch-all criminal law. Instead, the General Assembly has created a series of targeted statutes that criminalize specific deceptive conduct. Prosecutors charge cases based on the nature of the misrepresentation, the method used, and the type of property involved.

This structure gives prosecutors flexibility but also requires careful legal analysis to understand exposure.

Fraud by False Pretenses Under Virginia Code § 18.2 178

One of the most commonly charged business-related fraud offenses is obtaining property by pretense under Virginia Code § 18.2 178. This statute applies when a person intentionally misrepresents a material existing fact to obtain money, property, or a signature.

Virginia courts have consistently held that the misrepresentation must relate to a present fact, not a future promise. In Riegert v. Commonwealth, the Court of Appeals of Virginia emphasized that false pretenses require proof that the victim relied on a misrepresentation that existed at the time of the transaction.

The statute is frequently used in cases involving false financial statements, misrepresented ownership, or deceptive authority to act on behalf of a business.

Forgery Under Virginia Code § 18.2 172

Forgery is another common criminal fraud charge in business settings. Under Virginia Code § 18.2 172, it is a felony to forge, alter, or utter a document with intent to defraud.

Business forgery cases often involve checks, contracts, corporate resolutions, invoices, or electronic records. The key element is intent to defraud, not whether the document successfully caused loss.

In Fitzgerald v. Commonwealth, Virginia courts reaffirmed that even the attempted use of a forged document can satisfy the statute if intent to defraud is present.

Embezzlement Under Virginia Code § 18.2 111

Embezzlement criminalizes the fraudulent conversion of property that was lawfully entrusted to the defendant. This statute is frequently used in employment and fiduciary relationships.

Under Virginia Code § 18.2 111, the Commonwealth must prove that the defendant was entrusted with property and then wrongfully converted it for unauthorized use.

In Waymack v. Commonwealth, the Supreme Court of Virginia clarified that embezzlement hinges on breach of trust, not how the property was initially obtained. This makes embezzlement especially relevant in internal business disputes involving officers, managers, or employees.

Bad Checks and Financial Instruments Under Virginia Code § 18.2 181

Issuing a bad check with knowledge of insufficient funds is treated as a form of larceny under Virginia Code § 18.2 181. In business contexts, this statute is often charged when checks are used to obtain goods or services under false financial pretenses.

Intent is inferred from circumstances such as prior account activity, notice of insufficient funds, or repeated issuance of bad checks.

False Statements to Obtain Credit Under Virginia Code § 18.2 186

Virginia Code § 18.2 186 criminalizes knowingly false written statements regarding financial condition made to obtain credit or property. This statute frequently arises in loan applications, vendor credit arrangements, and financing transactions.

Courts require proof that the statement was materially false and that it was relied upon in extending credit.

The Virginia Governmental Frauds Act and Public Contracts

The Virginia Governmental Frauds Act, codified at Virginia Code § 18.2 498.3, is particularly important for businesses dealing with state or local governments. It criminalizes knowingly false statements, concealment of material facts, or use of false records in transactions involving public funds.

For companies operating in Loudoun County, this statute frequently applies to procurement contracts, certifications, compliance representations, and billing submissions.

Violations can result in felony charges, civil penalties, and debarment from future government work.

How Criminal Fraud Interacts With Civil Litigation

Criminal fraud investigations often proceed in parallel with civil disputes. Prosecutors can use statements made in civil litigation, discovery responses, and depositions. This overlap creates significant strategic risk.

Virginia courts do not automatically stay civil cases during criminal investigations. As a result, early legal coordination is essential.

The Practical Reality for Business Owners

Criminal fraud exposure changes everything. What might appear to be a business dispute can quickly escalate into a criminal matter if misrepresentations involve intent, false documents, or public funds.

Understanding these statutes allows business owners to recognize red flags early and seek counsel before civil problems become criminal ones.

In the next chapter, I explain how civil and criminal fraud cases intersect, why parallel proceedings are dangerous, and how Virginia courts manage these high-risk situations.

Chapter 9

How Civil and Criminal Fraud Cases Intersect in Virginia

When business fraud allegations move beyond private lawsuits and attract criminal attention, the legal landscape changes immediately. I have seen cases in Loudoun County where what began as a contract dispute quietly evolved into a criminal investigation because of how the parties handled the civil case. Understanding how civil and criminal fraud intersect in Virginia is essential for any business owner facing serious allegations.

Why Parallel Proceedings Are So Dangerous

Civil and criminal fraud cases often proceed at the same time. Virginia law does not automatically pause a civil lawsuit simply because a criminal investigation is underway. That means a business owner may be required to respond to civil discovery, sit for depositions, and produce documents while prosecutors are actively building a criminal case.

This overlap creates risk. Statements made in civil litigation are not protected from criminal use. Emails, sworn testimony, and document productions can be subpoenaed by the Commonwealth and used as evidence.

Virginia courts have repeatedly held that invoking the Fifth Amendment in civil proceedings does not stop the case. It merely allows an adverse inference to be drawn, which can severely damage a civil defense.

How Prosecutors Leverage Civil Litigation

Prosecutors often monitor civil litigation for leads. Civil pleadings can identify witnesses, theories, and documents that become roadmaps for criminal investigations.

In business fraud cases, civil discovery frequently uncovers internal communications, financial records, and approval processes that reveal intent. What was once a private dispute becomes a matter of public enforcement.

This is especially true in cases involving public contracts, financial institutions, or alleged misuse of entrusted funds.

The Strategic Trap of Inconsistent Positions

One of the most dangerous mistakes business owners make is taking inconsistent positions between civil and criminal matters. What may seem like a harmless explanation in a civil case can later be characterized as an admission in a criminal proceeding.

Virginia courts allow prosecutors to introduce prior sworn testimony as substantive evidence. There is no undoing that once it happens.

Coordinated legal strategy is essential from the outset.

When Courts Will Consider Staying Civil Cases

Virginia courts have discretion to stay civil proceedings in limited circumstances, but such stays are not automatic. Courts balance several factors, including prejudice to the civil plaintiff, the status of the criminal case, and the public interest.

In practice, courts are reluctant to halt civil litigation indefinitely. As a result, defendants must often choose between defending the civil case actively or protecting their criminal rights.

This decision must be made carefully and early.

Why Loudoun County Businesses Face Unique Exposure

Loudoun County sits at the intersection of private enterprise and government contracting. Many businesses operate in sectors that involve regulatory compliance, certifications, and public funds.

That proximity increases the likelihood that civil fraud allegations draw prosecutorial interest. The involvement of public money or trust elevates scrutiny.

Courts serving Loudoun County apply the same procedural rules as elsewhere in the Commonwealth, but the factual context often heightens stakes.

Evidence Preservation and Internal Investigations

Once criminal exposure is possible, evidence preservation becomes critical. Destroying or altering documents can create independent criminal liability.

At the same time, internal investigations must be conducted carefully to avoid creating discoverable materials that could later be used against the business.

Legal counsel should direct these efforts to preserve privilege and control risk.

The Practical Reality of Dual Exposure

Civil fraud threatens financial loss. Criminal fraud threatens liberty, reputation, and the future of the business itself. Treating one as separate from the other is a mistake.

Business owners must recognize that actions taken early in civil disputes often shape criminal outcomes.

Preparing for the Final Stage

Understanding how civil and criminal fraud intersect allows businesses to respond strategically rather than reactively.

In the final chapter, I explain what Loudoun County business owners should do the moment fraud is suspected, including immediate steps that protect legal rights and preserve options before damage becomes irreversible.

Chapter 10

What Loudoun County Business Owners Should Do the Moment Fraud Is Suspected

When fraud is suspected, timing matters more than certainty. One of the most damaging mistakes I see business owners make is waiting until they are absolutely sure something improper occurred before acting. By then, evidence may be gone, positions may be locked in, and legal exposure may already be expanding.

Virginia law rewards early, disciplined responses. It punishes delay.

This chapter is not about panic. It is about control.

Why the First 72 Hours Matter More Than You Think

The moment fraud enters the conversation, whether through internal discovery, a demand letter, or unusual financial activity, the legal risk profile changes. Emails, accounting records, contracts, and system logs immediately become potential evidence.

In Virginia, spoliation of evidence can lead to sanctions, adverse inferences, or independent liability. Even routine document destruction policies can become dangerous once fraud is suspected.

The first step is simple but critical. Preserve everything.

How to Secure Evidence Without Creating New Risk

Preserving evidence does not mean conducting an uncontrolled internal investigation. Poorly handled internal reviews often generate damaging documents that later become discoverable.

Communications should be limited. Instructions should come through counsel. Employees should not be interviewed casually or asked to provide written explanations without legal guidance.

The goal is preservation, not conclusions.

Why Businesses Should Avoid Confrontation Too Early

Confronting a suspected wrongdoer prematurely often backfires. It can lead to evidence destruction, coordinated stories, or retaliation claims.

In some cases, it can escalate a civil issue into a criminal one. Accusations made without full legal context can be misconstrued, documented, or weaponized later.

Strategic silence is often the smarter move.

How Early Legal Analysis Prevents Costly Missteps

Early legal involvement is not about filing suit immediately. It is about understanding whether the conduct at issue fits within Virginia’s narrow fraud framework or whether it belongs in contract, employment, or regulatory law.

This assessment shapes everything that follows. It determines whether litigation is viable, whether criminal exposure exists, and how communications should be handled.

In Loudoun County, where business disputes often intersect with technology, government contracting, and regulated industries, this analysis is especially important.

Courts serving Loudoun County expect precision. They do not reward improvisation.

When to Involve Law Enforcement and When Not To

Not every fraud issue should be reported immediately. Involving law enforcement too early can remove control from the business and limit strategic options.

In some cases, civil recovery is the priority. In others, criminal enforcement is necessary to stop ongoing harm. The decision depends on the facts, the evidence, and the risk profile.

Once authorities are involved, the timeline and strategy shift permanently.

How to Protect the Business While the Issue Is Evaluated

Businesses should consider temporary access controls, financial safeguards, and oversight adjustments that prevent further harm without signaling accusations.

These steps should be neutral, documented, and defensible. Overreaction can create liability just as easily as inaction.

Why Public Statements and Internal Emails Are So Dangerous

Anything written during this phase can surface later in litigation or investigation. Casual emails expressing suspicion or blame are frequently cited out of context.

This is not the time for informal commentary. Communications should be factual, limited, and purposeful.

The Final Strategic Reality

Fraud cases in Virginia are not won by outrage. They are won by preparation, evidence, and restraint.

Business owners who act early preserve options. Those who delay often find their choices narrowing rapidly.

Understanding Virginia’s fraud framework allows businesses to respond with clarity rather than fear. That clarity is often the difference between controlling a situation and being controlled by it.

Final Takeaway

Fraud in Virginia is rare, narrow, and unforgiving. Loudoun County businesses that understand the law, act early, and proceed deliberately are far better positioned to protect their interests, their reputation, and their future.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

Business Litigation Attorney for Loudoun County

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What counts as business fraud in Virginia

Business fraud in Virginia usually involves intentional deception to obtain money, property, a signature, or another advantage. The key is that the lie has to be about a present, material fact and it has to be made to cause the other side to act. If it is just a broken promise later, Virginia courts often treat it as a contract dispute rather than as fraud.

2. Is a broken promise automatically fraud in Virginia

No. A broken promise usually is a breach of contract, not fraud. Fraud requires proof the person intended to deceive at the exact moment they made the statement. If you cannot show that intent existed then, the case often gets dismissed early.

3. Can I sue for fraud and breach of contract at the same time in Virginia

Sometimes, yes. It depends on whether the fraud is genuinely independent of the contract. If the only wrong is that someone failed to perform what the contract required, Virginia courts tend to keep the case in contract law. If there was a pre-contract misrepresentation of an existing fact that induced you to sign, a fraud claim may be viable alongside a breach of contract claim.

4. What does “present material fact” mean in a fraud case

It means the statement must be about something true or false right now, and it must matter to the deal. For example, lying about ownership of assets, current financial condition, existing approvals, or actual authority to sign can qualify. Opinions, hype, and future predictions usually do not.

5. Are exaggerated sales claims fraud or just sales talk

Most exaggeration is treated as puffery rather than fraud. Virginia courts generally do not treat broad marketing claims such as “best,” “fastest,” or “guaranteed results” as actionable. Fraud is more likely when the statement is specific, factual, and provably false at the time it was made.

6. What does “clear and convincing evidence” mean for civil fraud in Virginia

It is a higher burden than typical civil cases. You need strong, credible proof, not just a 51 percent likelihood. This is one reason fraud claims are hard to win in Virginia and why they often fail without documents, admissions, or strong circumstantial evidence.

7. What kind of evidence actually proves fraudulent intent

Intent is usually proven through timing and contradictions. Things like internal emails, financial records showing impossibility, fake documents, prior denials of authority, or contemporaneous knowledge that a statement was false can help. Courts do not accept intent based only on the fact the deal later failed.

8. How do I prove they lied at the time they made the statement

You look for evidence that existed before or during the formation of the contract. For example, earlier reports, prior communications, board minutes, account statements, or compliance notices that contradict what they told you. The goal is to show that the falsity was baked in from the start.

9. What is “reasonable reliance,” and why does it kill fraud cases

Reasonable reliance means you acted on the statement in a way the court considers sensible. Virginia does not protect blind reliance. If you could verify the claim or investigate and you chose not to, the court may say you relied at your own risk.

10. If I did not do due diligence, can I still sue for fraud

Possibly, but it is harder. The more you could have verified, the more the defense will argue your reliance was unreasonable. That is especially true for sophisticated businesses, large transactions, or deals where records were available and you had the means to review them.

11. Do integration clauses and non-reliance clauses block fraud claims

They do not always completely block fraud claims, but they can seriously weaken them. Courts may question why you relied on alleged oral statements when the signed agreement says the written contract contains the entire deal. It becomes much harder to argue reasonable reliance.

12. What is constructive fraud in Virginia, and is it easier to prove

Constructive fraud involves a negligent or reckless misrepresentation that causes harm, without requiring proof of intent to deceive. It can be easier in theory because you do not have to prove intent. But you still must prove a false statement of present material fact, reasonable reliance, and damages, so many constructive fraud claims still fail.

13. Does Virginia recognize negligent misrepresentation for business disputes

Virginia is cautious here. In many commercial contexts, negligence-based misrepresentation claims run into the economic loss rule and the source-of-duty rule. If your losses are purely economic and tied to a contract, courts often push the dispute back into contract law.

14. What is the economic loss rule and why does it matter for fraud claims

The economic loss rule generally prevents tort recovery for purely economic losses when the duty arises from a contract. Fraud can sometimes avoid this because it involves an independent duty not to lie. But negligent misrepresentation claims often get blocked when they are basically contract issues.

15. What criminal charges are most common for business fraud in Virginia

Common ones include false pretenses, forgery, embezzlement, bad checks, and false statements to obtain credit. These are separate from civil fraud and can lead to criminal penalties, restitution, and reputational harm.

16. What is pretenses and how is it different from civil fraud

False pretenses is a criminal offense involving the intentional misrepresentation of a material fact to obtain property or money. Civil fraud focuses on private recovery and damages. Criminal cases focus on punishment and require proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

17. What is embezzlement and how does it show up in businesses

Embezzlement is when someone entrusted with money or property wrongfully converts it. It often shows up with employees, managers, bookkeepers, or partners who have authorized access and then misuse funds.

18. Can a civil business dispute turn into a criminal case

Yes. If there are allegations of forged documents, intentional misrepresentations to obtain money, or misuse of entrusted funds, prosecutors can get involved. Also, statements and documents produced in civil litigation can be used in criminal investigations.

19. If there is a criminal investigation, should I pause the civil case

Not automatically. Virginia courts do not always stay civil matters. That means you may face depositions and document production while criminal exposure exists. This is why coordinated legal strategy matters early.

20. Can I plead the Fifth in a civil fraud case in Virginia

You can invoke the Fifth Amendment, but it does not stop the civil case. The court may allow an adverse inference in the civil matter, meaning the judge or jury may assume the testimony would have been unfavorable.

21. What is the Virginia Governmental Frauds Act and who should worry about it

It affects businesses dealing with the Commonwealth or local governments, including Loudoun County. If a company falsifies or conceals material facts in government commercial dealings, it can trigger serious penalties. Contractors and vendors should be especially cautious with certifications, invoices, and compliance statements.

22. What should I do immediately if I suspect fraud inside my company

Preserve documents and control communications. Do not confront people impulsively or send accusatory emails. Secure access, preserve logs, and involve counsel early so the investigation is structured and privileged where possible.

23. What should I do if I think another company defrauded my business

Preserve all communications, contracts, invoices, and meeting notes. Identify the exact statements you relied on and when they were made. Then evaluate whether the misrepresentation was a present fact and whether reliance was reasonable. A disciplined early case assessment often determines whether Virginia law supports a viable fraud claim.

24. How long do I have to file a business fraud claim in Virginia

Many fraud based civil claims are subject to statutes of limitation that can depend on the theory and when the fraud was discovered or should have been discovered. Timing can be complicated, especially when concealment is involved, so early evaluation matters.

25. What are the biggest mistakes businesses make when alleging fraud in Virginia

The biggest mistakes are treating breach of contract as fraud, relying on vague accusations, failing to plead specifics, ignoring the reliance requirement, and waiting too long to preserve evidence. Virginia fraud cases require precision, not frustration.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Every case is unique. If you believe you have a claim, contact a qualified attorney immediately to discuss the specifics of your situation and the applicable statutes of limitation.