Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

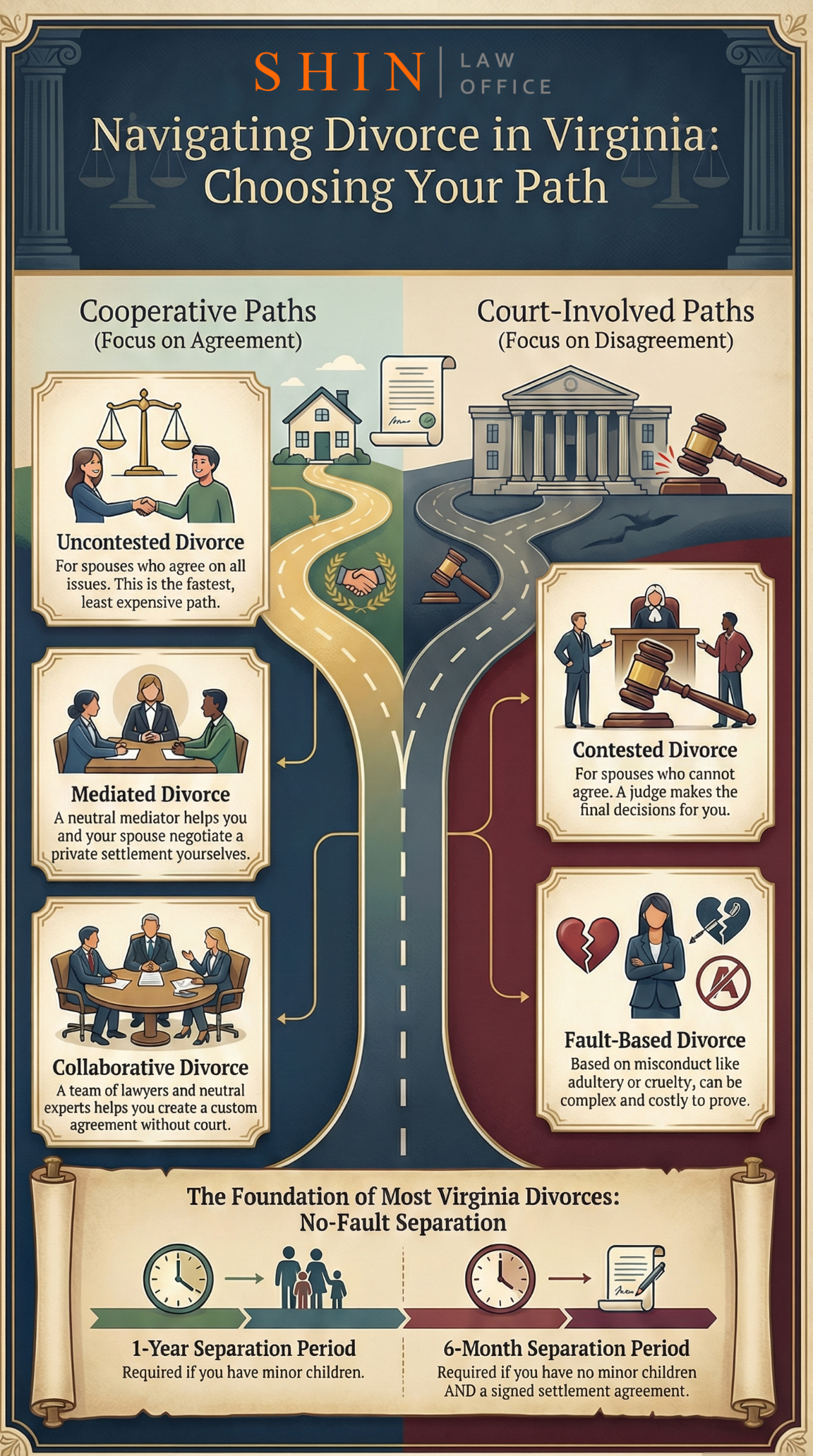

Divorce in Virginia isn’t one-size-fits-all. You have multiple paths from amicable, uncontested divorces to courtroom battles, and the right one depends on your situation. The quickest, least costly route is usually a no-fault, uncontested divorce (no court fight, just paperwork after a separation period). If you and your spouse can’t agree, a How to Protect Your Custody Rights in a Northern Virginia Divorcecontested divorce may be necessary, though alternatives like mediation or collaborative divorce can help you settle out of court. Virginia law offers both fault-based and no-fault grounds for divorce, each with specific requirements (e.g. proof of wrongdoing vs. a mandatory separation period (Va. Code Ann. § 20-91(A)(9), 2026)). As a Northern Virginia attorney, I’ll walk you through each type – what they mean, how they work, and special considerations for residents of Loudoun, Fairfax, Prince William, Arlington, Clarke, and Frederick Counties. By the end of this guide, you’ll have a clearer picture of which divorce path fits your needs and what to expect at each step.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Choosing the Right Divorce Path – Matching your situation with the appropriate divorce approach.

- Chapter 2: Uncontested Divorce – When both spouses agree on everything (the simplest path).

- Chapter 3: Contested Divorce – When you can’t agree: how court involvement works in Northern VA.

- Chapter 4: Fault Divorce – Divorces based on a spouse’s misconduct (adultery, cruelty, etc.) and their implications.

- Chapter 5: No-Fault Divorce – Divorces based on separation with no blame, the most common route in Virginia.

- Chapter 6: Collaborative Divorce – A team-based, no-court approach to negotiate a settlement with dignity.

- Chapter 7: Mediated Divorce – Using a neutral mediator to reach an agreement and avoid a trial.

- Chapter 8: Summary (Simplified) Divorce – Fast-tracking your divorce when qualifications are met for a simple case.

- Chapter 9: Virginia Divorce Process Step-by-Step – The legal roadmap from filing to final decree in Virginia.

- Chapter 10: Life After Divorce – What to expect post-divorce and tips for moving forward in Northern Virginia.

- References

Chapter 1: Choosing the Right Divorce Path

“How do I even start?” As a divorce attorney, I hear this question often. Divorce can feel overwhelming, but the first big decision is choosing how you’ll divorce. In Virginia, there are multiple divorce paths, and picking the right one can save you time, stress, and money. Let me share how I help clients in Northern Virginia, from Loudoun to Arlington, choose the approach that best fits their circumstances.

Assess Your Situation: I start by learning about your relationship with your spouse right now. Are you both able to communicate and cooperate? Have you already agreed on key issues, such as kids, property, or support? Or are you barely on speaking terms? The answers point us in different directions:

- If you agree on most issues, an uncontested divorce is often the smoothest path. That means you and your spouse work out a settlement and simply ask the court to approve it. This route is typically faster and cheaper because there’s no need to fight for a judge’s time.

- If you disagree on important issues (for example, who gets custody of the children, how to split assets, or whether someone was at fault for the marriage ending), you’re looking at a contested divorce. This involves court intervention – but keep in mind, “contested” doesn’t always mean a dramatic trial. Many contested cases settle before reaching the courtroom, especially through mediation or negotiation.

- Consider whether specific grounds (reasons) for divorce apply. Virginia has fault grounds (like adultery or cruelty) and a no-fault ground (separation for a period of time). If your spouse seriously wronged you (e.g. cheated or was abusive), you might lean toward a fault divorce to hold them accountable or to avoid a long wait. But proving fault can be difficult and isn’t necessary if a no-fault approach meets your needs. We’ll delve into details in later chapters.

- Think about your priorities: Is speed your main concern? Keeping things amicable for the children? Getting what you’re legally entitled to even if it means a fight? For instance, an uncontested no-fault divorce is the quickest once the requirements are met, while a contested or fault-based divorce may provide a sense of justice or financial protection at the cost of time and stress.

Explore Alternatives: Just because you have disagreements doesn’t mean you must battle in court. In Northern Virginia, we have robust mediation and collaborative divorce options (Chapters 6 and 7 cover these). If both spouses are willing to negotiate with some help, these alternatives can turn a potentially contested case into a cooperative one. For example, I’ve seen high-conflict couples in Fairfax avoid a trial by engaging a professional mediator who helped them find middle ground on tough issues. Likewise, I’ve guided spouses through collaborative divorce, where we signed an agreement to work out a settlement without involving a judge, and it kept the process civil and private.

Safety and Power Imbalances: I approach each case with empathy. If there’s been domestic violence or you feel unsafe with your spouse, that steers us away from direct collaboration or mediation. Your well-being comes first. In such cases, a court-managed process might be necessary to ensure fairness and protection (Virginia courts can issue protective orders and other measures as needed). For example, in one Prince William County case, my client had suffered abuse; we knew a traditional negotiation wasn’t appropriate, so we proceeded with a fault-based, contested divorce to have the court’s oversight and protection throughout.

Legal Advice Matters: Choosing a path isn’t a permanent commitment – you can start cooperatively and later involve the court if needed, or vice versa. But making an informed choice early on sets the tone. I always advise speaking with a Virginia family law attorney (it doesn’t have to be me!) about your options. Laws and local court procedures can affect your strategy. For instance, if you have minor children in Loudoun County, you’ll be required to complete a co-parenting class as part of the process (we’ll discuss this further). An experienced lawyer can explain these nuances. Even if you ultimately handle your divorce yourself, an initial consultation can help clarify which route aligns with your goals.

In summary, choosing the right divorce path is about balancing your emotional needs, legal rights, and practical constraints. This chapter was a bird’s-eye view; now, let’s dive deeper into each specific type of divorce, so you understand exactly what each entails.

Chapter 2: Uncontested Divorce

An uncontested divorce is the most straightforward path to ending a marriage in Virginia. “Uncontested” means you and your spouse have resolved all the major issues – from how to divide your property to who gets the kids on weekends – before asking the court to finalize the divorce. Essentially, there’s nothing left for a judge to decide, so the court’s role is just to review and approve your agreement and grant the divorce. In my Northern Virginia practice, I often see a sense of relief in clients who realize they can handle things amicably. Here’s what an uncontested divorce looks like:

Key Features:

- Agreement on All Issues: Both spouses must agree on the terms of the divorce. This typically involves a written Property Settlement Agreement (also called a separation agreement) that outlines arrangements for property division, child custody and visitation, child support, spousal support, and related matters. For example, a couple in Fairfax County might agree that one keeps the house and the other keeps an equivalent value in investments, or that they’ll share custody of the children on a week-on/week-off schedule. If there’s even one issue you haven’t agreed on, the case isn’t truly uncontested and could become contested on that point.

- No Court Fight: Because all matters are settled, you generally do not need multiple court hearings. In fact, in Virginia, you often don’t need any in-person hearing for an uncontested divorce. Many Northern Virginia courts allow what’s known as a “divorce by affidavit” or deposition – you submit sworn written testimony to prove your case instead of appearing in court in front of a judge (Va. Code Ann. § 20-106, 2026). I regularly help clients prepare affidavits that state the required facts (such as residency and separation details). Once we file that and the settlement agreement, a judge can review the file and sign the final divorce decree without a formal hearing. This is a huge time-saver and eliminates the anxiety of a courtroom.

- Faster Resolution: Uncontested cases typically move faster than contested cases. There’s no drawn-out litigation process – no discovery, subpoenas, or trial scheduling. Once you meet the legal requirements (more on that next), the timeline largely depends on administrative factors like how quickly the court can process paperwork. In many Northern Virginia jurisdictions, an uncontested no-fault divorce can be finalized within a few weeks to a couple of months after all paperwork is filed. For example, in one Arlington County case I handled, we filed the divorce complaint right after the required separation period ended, and the judge entered the final decree about a month later. (In some counties, the wait can be as short as 1–6 weeks after filing, depending on the judge’s docket and whether all paperwork is in order (Virginia Family Law Center, 2025).) This is lightning-fast compared to contested divorces that might drag on for a year or more.

- Lower Cost & Stress: Generally, uncontested divorces are far less expensive, with fewer court appearances and fewer legal tasks. Many of my clients handle an uncontested divorce with minimal attorney involvement – sometimes just a consultation and document review. The emotional toll is also lower: you’re not in a battle; you’re cooperating to end the marriage respectfully. This can be especially beneficial if you have children, as it sets a cooperative tone for co-parenting after divorce.

Legal Requirements: Even if you and your spouse agree on everything, you must satisfy Virginia’s basic legal requirements for divorce. Virginia is a “no-fault” state for uncontested divorces, meaning the usual ground is that you’ve lived separate and apart for the required time (see Chapter 5 on No-Fault divorce). Specifically, Virginia law requires that the spouses be separated without cohabitation for at least one year, or six months if you have no minor children and have a signed separation agreement in place. This is crucial: you cannot file and finalize an uncontested no-fault divorce until that period has passed (Va. Code Ann. § 20-91(A)(9), 2026). For example, if you and your husband in Loudoun County decide in January to divorce and you have two kids, you’ll need to live apart (or at least live in the same house but truly separate – more on that later) until at least the next January before the court will grant a divorce. If you have no kids and you sign a separation agreement, you could be done in six months. I always verify that the separation requirement is met before we proceed with filing – the last thing you want is the court rejecting your paperwork because you filed too soon.

Example: I worked with a couple from Prince William County who wanted a simple, drama-free divorce. They had no children and had already divided their belongings (furniture, bank accounts, etc.) informally. They wrote up a property settlement agreement with my guidance and signed it. Then they lived apart for six months – one moved in with a relative – to meet the legal requirement. We filed for divorce on no-fault grounds, citing a six-month separation with no minor kids. We submitted affidavits instead of having a live witness testify, per Virginia law. The judge reviewed our submission and signed the divorce decree without requiring us to come to court. The entire process, once the six-month separation was over, took about two months, and neither spouse ever had to set foot in a courtroom. This was a textbook uncontested divorce.

Northern Virginia Considerations: Courts in our area are quite accustomed to uncontested divorces – they probably process thousands every year. Fairfax Circuit Court, for instance, has a specific procedure and forms for uncontested divorces (often handled by a commissioner or a judge in chambers). During COVID-19, some courts even allowed divorces to be finalized completely remotely via affidavits and email filings; many of those convenient procedures have remained in place. One thing to note: if you file an uncontested divorce without a lawyer (pro se), each county’s Circuit Court might have slightly different paperwork requirements. Always check the local court’s website or clerk’s office. For example, Fairfax County provides a pro se divorce brochure with detailed instructions, and Loudoun County, at one point, required divorces to be filed by mail or via drop box (a pandemic-era rule). These local quirks don’t change the law, but you need to follow them to avoid delays. In any case, uncontested divorces are the least adversarial way to end a marriage – they demonstrate that you and your spouse can work together, at least on the exit plan, which often bodes well for how you’ll handle things after divorce.

In sum, if you and your spouse are on the same page about ending the marriage and can collaborate on the terms, an uncontested divorce is usually the way to go. It’s private, quick, and efficient. In the next chapter, we’ll look at the opposite scenario: what happens when you don’t agree – the world of contested divorce.

Chapter 3: Contested Divorce

Sometimes, despite best efforts, spouses just can’t agree on the terms of their divorce. Maybe you differ on who should have primary custody of the kids, how much support is fair, or how to split a beloved home. Maybe one of you isn’t ready to divorce at all. When any major issue is in dispute, you have a contested divorce on your hands. In a contested divorce, you essentially ask the court to step in and decide the unresolved issues. As an attorney practicing in Northern Virginia’s busy courts (Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, etc.), I can tell you that contested divorces are common – but each one is unique in its conflicts and can range from moderately challenging to extremely bitter. Here’s what to expect:

Definition: At its core, “contested” means there’s something to fight over. It could be the grounds for divorce (for instance, one spouse alleges adultery and the other denies it – see Chapter 4), or, more often, it’s about the outcomes: money, children, property. For example, I had a case in Fairfax County where the spouses agreed on getting divorced and even agreed on dividing their assets, but they fought intensely over custody of their two children. That one contested issue meant the divorce was classified as contested and required court intervention to resolve it.

The Court’s Role: In a contested divorce, the Circuit Court (that’s the level of court in Virginia that handles divorces) becomes actively involved. The process typically goes like this: one spouse (the plaintiff) files a Complaint for Divorce stating what they want and on what grounds (fault or no-fault). The other spouse (the defendant) files an Answer – often with their own demands or even a Counterclaim for divorce. If the other side does not file, it could result in a “default” divorce; if both parties participate and disagree, the case proceeds as a civil lawsuit. This means discovery (the exchange of financial documents, answering questions under oath, depositions, etc.), motions (requests to the court for temporary relief or to compel information), and, eventually, a trial if you never settle. Essentially, the judge (or sometimes a jury, though jury trials in divorce are rare in Virginia) will decide the issues you can’t resolve yourselves.

Temporary Orders: Contested divorces can take many months or even years to conclude, so you often can’t wait until the end to sort out things like custody or support. Virginia law allows you to seek pendente lite (temporary) orders while the case is pending (Va. Code Ann. § 20-103, 2026). For instance, if you file for divorce in Arlington and you need financial support immediately, or you need a schedule set for the kids while the case is ongoing, you can request a pendente lite hearing. The court might order one spouse to pay a certain amount of spousal or child support each month, or set temporary custody/visitation arrangements, to maintain stability until the final decree. In one of my Loudoun County cases, we got a temporary order granting my client exclusive use of the marital home (meaning the spouse had to move out) and temporary child support, because living together during the proceedings was unsafe in that situation. These orders expire when the divorce is finalized, but they’re crucial in contested cases to get you through the litigation period.

Mediation and Court-Mandated Steps: Just because a case is contested at first doesn’t mean it will end in a trial. In fact, most contested divorces eventually settle through negotiation – sometimes on the courthouse steps on the eve of trial. Virginia courts encourage this. If you have children, the court will require at least an initial orientation session about mediation (Va. Code Ann. § 20-124.4, 2026) and also require both parents to attend a parenting education seminar within a certain time (at least in contested cases – see Va. Code Ann. § 20-103, 2026). In Northern Virginia, each county has approved seminars (often called “Families in Transition” or similar – Loudoun’s FITS program, for example) that educate parents on how to co-parent and reduce the impact of conflict on kids. As for mediation, courts in Fairfax, Prince William, and other counties often refer the parties to a mediator early on, especially for custody and visitation disputes. The initial orientation is free, and if both parties are willing, you can proceed with mediation. I’ve had contested cases where, after months of fighting, both sides finally sat down with a mediator and reached a full settlement – thereby converting the case to “uncontested” for final paperwork. Important: You’re not forced to settle; if mediation doesn’t produce an agreement, you still have the right to go to trial and have the judge decide. But it’s wise to seriously consider any chance to settle – trials are costly and unpredictable.

Timeline and Stress: There’s no sugarcoating it: contested divorces can be long and stressful. Northern Virginia courts (particularly Fairfax, being a high-population jurisdiction) often have crowded dockets. From filing to trial, a year or more is not unusual if you must litigate everything. Every stage – preparing discovery, attending depositions, waiting for hearings – adds time. And because you’re in conflict, the process can take an emotional toll. You’ll likely need to discuss in court personal aspects of your marriage and finances. For example, in a contested fault divorce in Fairfax I handled, we had to hire a private investigator and subpoena phone records to prove adultery, then present that evidence in a public courtroom. It was draining for my client. I always remind clients to take care of themselves during this process – lean on friends, counseling, etc. – and keep focused on the light at the end of the tunnel.

Costs: Naturally, a contested divorce is more expensive than an uncontested one, especially if it goes all the way to trial. Attorney’s fees mount with every motion and hearing. In some cases, one spouse can be made to contribute to the other’s fees (for instance, if there’s a big disparity in income or if one party behaved obstructively in the litigation), but you should plan for high costs if you can’t reach a settlement. I’ve seen contested cases spend tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees – sometimes more than the amount at stake in a property dispute. That’s another reason why, if a fair settlement is on the table, it can be smarter to compromise than to spend $20,000 fighting over something worth $10,000.

Example: A couple in Frederick County (the Winchester area) reached a breaking point over finances. The wife suspected the husband was hiding assets and the husband vehemently disagreed on spousal support. We filed in Circuit Court; the case was contested. Over a year, we engaged in discovery – including subpoenas of bank records and hiring a forensic accountant. We also navigated court appearances: a pendente lite hearing set temporary support so my client (the wife) could pay bills, and a pre-trial conference to schedule the trial date. Both spouses had to attend the mandatory parenting class since they had a 10-year-old (even though they didn’t agree on custody, they sat in the same seminar learning about co-parenting – awkward but useful). We attempted mediation on the judge’s recommendation. It partially worked: they settled the property and debt issues in mediation, but not spousal support. Ultimately, we went to trial on spousal support and the judge decided an amount halfway between what each had proposed. It was a classic contested divorce scenario – a mix of settlement and court decision. By the end, both were just relieved it was over.

Bottom Line: In a contested divorce, be prepared for a marathon, not a sprint. The court will be actively involved in your life – making decisions that you and your spouse couldn’t make yourselves. My role as your attorney in such cases is not only to fight hard for your interests but also to guide you through the procedural maze and explore opportunities to resolve issues without further combat when possible. It’s a tough process, but with preparation and good legal support, you can get through it and come out the other side. Next, we’ll discuss fault and no-fault grounds – concepts that apply to both contested and uncontested divorces and often confuse people.

Chapter 4: Fault Divorce

Virginia is somewhat unique among states in retaining fault-based divorce options. A fault divorce is one in which one spouse blames the other for the marriage ending, under specific grounds defined by law, and uses that misconduct as the basis for seeking a divorce (instead of relying solely on separation). While no-fault divorces are more common today (we’ll cover those next), it’s important to understand fault grounds, because they can impact strategy, timing, and even financial outcomes like spousal support.

Fault Grounds in Virginia: The Virginia Code lists several fault grounds on which you can file for divorce (Va. Code Ann. § 20-91(A), 2026). The main ones are:

- Adultery (and related acts): Voluntary sexual intercourse by a spouse with someone not their spouse. The statute also includes sodomy or buggery outside the marriage as equivalent grounds. Adultery is considered a very serious marital wrong in Virginia – so much so that, if proven, it immediately entitles the innocent spouse to file for divorce without any waiting period. For example, if you discover your spouse cheated on you in July, you theoretically could file for divorce in August citing adultery (no need to be separated for a year). However, proving adultery is challenging: courts require “clear and convincing” evidence, often a combination of circumstances like emails, texts, or a private investigator’s report. Direct evidence (like catching in the act) is not always available, but you need more than suspicion. I often explain to clients that adultery as a fault ground can be an uphill battle – it’s emotionally charged and can be expensive to substantiate.

- Cruelty: This means conduct that endangers life, limb, or health, or causes reasonable apprehension of bodily harm. In plain language, physical abuse or extreme emotional abuse. A single instance of serious violence can qualify (e.g. a severe beating), or a pattern of abusive behavior. If one spouse is abusive, the other can claim cruelty. Desertion is often mentioned alongside cruelty – that’s when a spouse willfully and unjustifiably leaves the marriage (abandons) with the intent to desert. Constructive desertion can be claimed if one spouse’s behavior forces the other to leave for self-protection (for instance, fleeing an abusive situation). Under Virginia law, you must wait one year from the date of the cruelty or desertion before you can be granted a final divorce on these grounds. (You could file earlier and just have the case pending until the year passes.) This essentially functions as a waiting period, possibly to allow for reconciliation or to ensure the problem is ongoing. For example, if your husband violently attacked you on January 1, 2025 and you leave the home, you could file right away citing cruelty, but the divorce wouldn’t be finalized until at least January 1, 2026.

- Felony Conviction: If your spouse is convicted of a felony and sentenced to more than one year of imprisonment, and you have not cohabited since learning of the conviction, that is also a fault ground. The classic scenario is a spouse goes to prison for a serious crime; the other spouse can divorce them due to the conviction. This ground also doesn’t require a separation period – once the conviction and sentence meet the criteria, you can file.

- (There are a couple of archaic grounds technically in the code, like natural impotency or unknowingly marrying your cousin, but those are rarely relevant. Also, note “desertion” encompasses what people think of as abandonment.)

Why Pursue a Fault Divorce? Given that no-fault divorce is available (and often simpler), why would someone choose a fault-based approach? A few reasons:

- Timing: As mentioned, adultery or felony conviction allows you to bypass the usual separation period. Some clients feel strongly about not waiting a year to divorce a cheating spouse. However, beware – just because you file for adultery immediately doesn’t mean the divorce will be resolved faster. If the accused spouse contests the adultery claim, the case can still take a long time to litigate, gathering evidence and possibly going to trial. So you might gain an initial time advantage, but then spend it in court battles.

- Moral or Emotional Validation: Sometimes a spouse wants the public record to reflect the other’s wrongdoing. It can be a form of validation or even leverage in negotiations (“I’ll file on adultery grounds if you don’t agree to XYZ”). Keep in mind, judges in Virginia do not write scathing condemnations in divorce decrees; they’ll just note that the divorce was granted on a particular ground.

- Financial Reasons: Fault can affect spousal support. Virginia law states that a spouse who has committed adultery is generally barred from receiving alimony (permanent spousal support) unless denying support would be a “manifest injustice”. In practice, if Husband cheats and Wife files for divorce, Wife can use adultery as a basis to potentially avoid paying Husband any spousal support. I had a case in Arlington where this was pivotal: my client was the primary earner, her husband had cheated, and by establishing adultery, we ensured he couldn’t claim alimony from her (Va. Code Ann. § 20-107.1(B), 2026). Other fault grounds (like cruelty or desertion) can be considered by the judge when dividing property or deciding support, but adultery has that specific statutory bar on support.

- Leverage: Because fault grounds can be embarrassing or costly to prove, sometimes merely alleging them can put pressure to settle. I’ve seen a spouse agree to more favorable divorce terms to avoid having details of an affair exposed in court. (It’s not exactly blackmail – more like a strategic consideration during settlement talks.)

The Realities of Fault Cases: If you pursue a fault divorce, be prepared for a higher-conflict process. You are effectively accusing your spouse of misconduct, which often makes them defensive and angry. The case may air dirty laundry. For example, proving adultery might involve subpoenas of phone records, text messages, hiring a private investigator to testify about observing the spouse with another person, etc. It can feel invasive. Additionally, there’s a concept called “corroboration” in Virginia divorce law – even if both spouses admit to a fault ground, you typically need a third-party witness or evidence to corroborate it (this is an old rule to prevent collusion). So you can’t simply both agree “yes, I cheated” and get an adultery divorce without some independent proof.

Defense and Recrimination: If you file on fault grounds, your spouse might countersue you for fault as well. It’s not uncommon to see dueling claims – e.g. Wife files accusing Husband of cruelty, Husband responds accusing Wife of desertion – especially if each feels wronged. Virginia law allows the court to grant a divorce on either party’s fault if proven. There’s also a doctrine of recrimination, which is basically “both of you were at fault, so nobody gets the divorce on fault grounds.” In practice, courts often just end up granting a no-fault divorce if both were misbehaving, rather than deny a divorce entirely. So fault can get legally complex.

Northern Virginia Angle: Judges in Northern Virginia (and, frankly, everywhere) are aware that fault cases can consume a lot of court time. There’s a bit of an adage: “Courts prefer no-fault divorces if possible.” I’ve observed in Fairfax Circuit Court that if a case starts as an adultery divorce but the evidence is shaky or it’s mostly being used as leverage, judges subtly encourage parties to consider switching to no-fault grounds later or to reach a settlement. The courts will certainly hear your fault case if you persist – I’ve tried fault cases to conclusion – but they will hold you to the evidentiary standards strictly. And if you haven’t met the burden of proof, the fault claim will be denied. (You could still get a divorce on no-fault grounds after the requisite separation period, as a fallback.)

Example: In a Loudoun County case, my client was a husband whose wife had left him and moved in with another man. We filed for divorce on grounds of adultery and desertion. We had photos from a private investigator of the wife and her new partner, as well as explicit admissions in text messages. This gave us a strong case. The wife, through her attorney, initially fought back, denying the affair and accusing my client of cruelty (which we believed was a fabricated claim). As the evidence mounted, we reached a settlement: the wife agreed to a no-fault divorce with no spousal support for her (likely because she knew the adultery could be proven and she’d be barred from alimony anyway) and an agreeable custody arrangement for their child. In the end, the divorce decree was entered on “one year separation” grounds – technically no-fault – but our preparation of a fault case clearly influenced the outcome. The client was satisfied because the financial outcome was fair and we avoided the spectacle of a trial, although we were ready for one.

Takeaway: Fault divorces are available in Virginia for serious situations and can be a necessary tool, especially in cases of abuse or infidelity that has significant consequences. But they are more complex and combative by nature. I always explore with clients whether the benefits of a fault approach outweigh the downsides. Sometimes, pursuing fault is absolutely the right call (say, for safety reasons in an abuse case, or to prevent an adulterous spouse from getting support). Other times, even if fault occurred, it might be wiser to proceed without playing the blame game in court, focusing instead on a quicker no-fault resolution. Remember, you can still feel morally vindicated and heal without having a judge formally declare your spouse “at fault” – and you can still get a fair division of assets and support in a no-fault divorce. Speaking of which, let’s talk about no-fault divorce next, which is how the majority of Virginia divorces are handled.

Chapter 5: No-Fault Divorce

Most divorces in Virginia – especially in Northern Virginia – are ultimately no-fault divorces. A no-fault divorce is one where neither spouse has to prove the other did anything wrong to cause the breakup. Instead, the marriage is dissolved because the couple has lived apart for the required period of time with the intent that the separation be permanent. This approach can reduce conflict and often simplifies the process, since you’re not delving into the messy details of why the marriage ended – the law doesn’t require you to. Let’s unpack how no-fault divorce works in Virginia and why it’s the go-to option for many.

The Basics: Under Virginia law, the ground for a no-fault divorce is that you have lived “separate and apart” continuously for a certain period (Va. Code Ann. § 20-91(A)(9), 2026). There’s no requirement of proving any misbehavior or wrongdoing by either spouse. The required separation period is:

- One Year – if you have minor children in common, or if you haven’t signed a written separation agreement.

- Six Months – if you have no minor children and have signed a written separation agreement resolving all issues (property, support, etc.).

In either case, during the separation, you must have the intent for the separation to be permanent (in other words, you’re not just on a temporary break or expecting to reconcile). At the end of that period, you can file for divorce, and the court can grant it on the basis of having been separated for the statutory time.

“Separate and Apart” Defined: People often ask, what does it mean to live separate and apart? The ideal scenario is you and your spouse physically live in different residences for the whole period. But in places like Northern Virginia, where the cost of living is high, I’ve seen many couples who separate but continue living under one roof (for financial or children’s stability reasons). Is that allowed? Yes – if you truly live as though you are separated roommates, not as a married couple. Virginia courts have recognized in several cases that spouses can be “separated” while in the same house, but you must intentionally cease acting as a married unit. Practically, this means you should sleep in different bedrooms, stop sexual relations, minimize shared meals or activities, don’t present yourselves as a couple to the outside world, and ideally even split household chores and finances to an extent. You might have a witness (like a friend or family member) who can later testify that, despite the shared address, you were essentially living independent lives. I’ve advised clients in Fairfax who cannot afford separate homes on how to structure an in-home separation – it’s doable, but you need evidence to back it up. For instance, one couple drafted a simple agreement and daily log that they would live separately under the same roof starting a certain date, and a close friend who visited often later served as a corroborating witness that they indeed were not acting married during that time.

Procedure: With a no-fault divorce, once you’ve met the separation duration, the process is relatively straightforward (especially if it’s uncontested). You file a Complaint citing separation as the ground for the required period. You’ll need to prove to the court that the separation time was met and that at least one of you was a Virginia resident for 6+ months before filing (residency is required for the court to have jurisdiction, per Va. Code Ann. § 20-97, 2026). Proof of these can be given via affidavit or testimony. Typically, one spouse (or a witness) testifies to the date of separation and that it’s been continuous, etc., and also attests to the residency. For example, I often prepare an affidavit for the plaintiff in an uncontested no-fault case stating: “We separated on May 1, 2024, and have lived separate and apart without cohabitation since then, which as of today exceeds one year. During this time, we intended to end the marriage. Additionally, I have been a resident of Virginia for many years (or since X date, which is more than 6 months before filing).” A similar statement can come from a corroborating witness affidavit, though a recent change in Virginia law (as of July 2021) simplified uncontested divorces by no longer requiring a witness affidavit in addition to the party’s affidavit in many cases. The point is, evidence of separation and residency must be provided, but it’s usually a routine step.

Advantages of No-Fault:

- Less acrimony: Since you’re not accusing each other of misconduct in the legal paperwork, it often keeps the temperature lower. Even if one spouse cheats or misbehaves, choosing a no-fault approach can sometimes help keep negotiations civil. You’re essentially saying, “We’re divorcing because it’s not working out, period,” rather than, “I’m divorcing you because you’re a bad person.” Emotionally, that can save some pain (though it’s not always that simple).

- Privacy: No-fault cases don’t require airing personal dirty laundry in court. The reasons behind the separation can remain private. In contrast, a fault divorce for, say, cruelty could require detailed testimony about fights or abuse, which becomes part of the public record. Many of my clients prefer to keep things as discreet as possible, and no-fault is conducive to that.

- Judicial Efficiency: Courts appreciate not having to adjudicate fault if it’s not necessary. A no-fault case typically only needs a brief hearing (or just a review of documents) to be finalized, rather than a multi-day trial over who did what. This can translate to getting a hearing date sooner and finishing the case more quickly.

- Flexibility in Settlement: Even if some bad behavior occurred, using no-fault grounds doesn’t prevent you from negotiating terms that take that behavior into account. For example, if one spouse’s affair blew up the marriage, the other spouse might feel entitled to a bit more of the marital assets or a more favorable custody schedule. You can negotiate those things in a property settlement agreement without asking the court to rule on fault. In practice, I’ve brokered settlements where, although we filed no-fault, the knowledge of one spouse’s misconduct informally influenced the compromises (say, the guilty party agreed to pay a bit more spousal support as a gesture). The final divorce paperwork, however, simply cites separation as the reason, keeping the official record clean.

When No-Fault Isn’t Truly No-Fault: It’s worth noting that even in no-fault divorces, the underlying issues can be contentious. You might have a contested divorce that’s still “no-fault” in grounds. For instance, a couple can disagree fiercely on child custody and go through a contested court process, but neither alleges fault grounds – they just proceed after a year’s separation and let the court decide custody. So “no-fault” doesn’t always equal “uncontested” or amicable, and vice versa. It refers solely to the legal grounds for divorce. I’ve had a case where both parties committed adultery during a long separation; rather than battle it out, they mutually decided to ignore the faults and just get divorced on the one-year separation ground, while still litigating how to divide their property. This saved them from a mini-trial on fault and kept the focus on the practical matters.

Example: A couple in Clarke County had grown apart over the years. There was no dramatic event – they just drifted. They agreed to separate and did so, with one renting an apartment in Winchester. They had a child, so they knew they’d have to wait a year to divorce. During that year, they worked out an agreement on their own for sharing custody and dividing their assets (which were modest). By the time they hit the one-year mark, they were essentially done negotiating. We filed a no-fault divorce for them, reciting that they’d been separated for over one year. The wife testified briefly at an ore tenus hearing (an informal testimony in front of a judge), confirming the separation date and that they hadn’t reconciled, etc. The husband had waived his right to be at the hearing (since everything was agreed). The judge reviewed their agreement, found it reasonable, especially regarding child support/custody, and approved it, granting the divorce then and there. This is a classic example of a no-fault divorce that was also uncontested – as smooth as it get,s given the circumstances.

Legal Tidbits: You might wonder, what if one spouse doesn’t want to divorce? In a pure no-fault scenario, can one prevent the divorce by not agreeing? In Virginia, as long as you fulfill the separation and residency requirements, either spouse can pursue a no-fault divorce even if the other doesn’t “agree”. The unwilling spouse cannot stop the divorce – they can drag it out a bit if they contest details, but they can’t ultimately prevent it. This is by design; Virginia moved away from requiring mutual consent for divorce (except that, if both agree, you can use the six-month shortcut if there are no kids). So, sometimes I handle cases where we’re doing a no-fault divorce and the other party is uncooperative or missing. We might have to serve them and do a default, but after the one-year separation, the court will grant the divorce with just one spouse’s testimony, if the other never responds.

No-Fault Doesn’t Mean No Consequences: One last point – just because the ground is “no-fault” doesn’t mean fault is irrelevant to everything. As mentioned in Chapter 4, serious fault like adultery can impact spousal support awards even in a no-fault divorce (e.g., if evidence of adultery comes out, the judge can deny alimony to the adulterous spouse). Also, if a spouse’s bad behavior had economic consequences (like they spent a bunch of money on their affair partner, or they were abusive and it affected the family), a judge can consider that under the factors for equitable distribution or support. So, “no-fault divorce” is a bit of a misnomer in that marital fault can still creep in through the back door when deciding money and children. The difference is that you’re not formally asking the court to grant the divorce because of the fault.

In conclusion, no-fault divorce is often the path of least resistance in Virginia’s legal system. It requires patience to get through the separation period, but it spares you from proving wrongdoing. For many, it’s a dignified way to end a marriage with minimal court drama. Now that we’ve covered both fault and no-fault grounds, let’s shift to processes that can help resolve divorces without full-blown litigation – collaborative divorce is up next.

Chapter 6: Collaborative Divorce

Imagine a divorce process where, instead of gearing up for battle, both spouses and their attorneys commit to working together as a team to find solutions. That’s the essence of collaborative divorce. It’s a relatively newer approach (now codified in Virginia law) that offers a structured, cooperative alternative to the courtroom. As an attorney trained in collaborative law, I’ve seen this process transform the way couples divorce – turning a potentially adversarial ordeal into a problem-solving exercise. Let’s explore how collaborative divorce works, especially here in Northern Virginia.

What Is Collaborative Divorce? Collaborative divorce is a voluntary dispute-resolution process. Both spouses hire their own collaborative attorneys, who are specially trained in this approach. Everyone signs a Collaborative Participation Agreement at the outset, which basically says: We agree to negotiate a mutually acceptable settlement without involving the court, to share information transparently, and to focus on the well-being of the entire family. Importantly, the agreement includes a unique clause: if either party later decides to abandon the collaborative process and go to court, both collaborative attorneys must withdraw, and the spouses have to hire new lawyers for litigation. This “disqualification provision” might sound scary, but it’s actually the glue of the process – it aligns everyone’s incentives toward reaching a settlement because nobody wants to start over from scratch.

The Collaborative Team: In addition to the attorneys, spouses can jointly enlist neutral professionals to address specific issues. Common team members include:

- A Financial Specialist (often a certified divorce financial analyst or accountant) to help gather and analyze financial data, create budgets, and propose options for dividing assets or handling support.

- A Divorce Coach (typically a licensed counselor or therapist) to help manage the emotional dynamics and improve communication between the spouses during negotiations. Sometimes each spouse has their own coach.

- A Child Specialist (if you have children) who can represent the kids’ needs in the process – they might talk to the children (if age-appropriate) or just help the parents develop a healthy co-parenting plan.

These professionals are neutral, which means they aren’t advocating for one side or the other; they’re there to facilitate a fair and informed resolution. In one collaborative case in Fairfax, for instance, we had a financial neutral who helped the couple develop several property division scenarios and a child specialist who provided input that shaped a very detailed parenting plan for their two young kids. Both parents trusted these experts’ input, which made it easier to agree on final terms.

The Process: Collaborative cases proceed through a series of face-to-face meetings (in person or via Zoom, etc.). At the first meeting, ground rules are set (like treating each other respectfully, not interrupting, etc.), and the main issues to be resolved are identified. Subsequent meetings tackle those issues one by one. The spouses speak for themselves (it’s not just lawyers talking) and everyone brainstorms solutions. The atmosphere is usually much less formal than a courtroom – I often have these meetings around a conference table, sometimes with coffee and snacks. The goal is to create a safe space for negotiation.

We might have joint sessions with all professionals or break-out sessions with just the financial neutral to handle asset questions. There’s an open exchange of information – no hiding documents or playing “gotcha.” In fact, the collaborative agreement typically obligates both parties to provide full and honest disclosure of relevant info (bank statements, income, etc.), without formal discovery. This openness saves time and money that would otherwise be spent on subpoenas and depositions in a litigated case.

Northern Virginia’s Collaborative Community: Our area has an active collaborative law community. Many family law attorneys in Fairfax, Arlington, Loudoun, etc., are part of practice groups that regularly handle collaborative cases. Virginia adopted a version of the Uniform Collaborative Law Act effective July 1, 2021 (Va. Code Ann. §§ 20-168 through 20-179, 2026), which gives legal framework to the process. The law sets standards (like what a valid participation agreement must include, the confidentiality of collaborative discussions, and the disqualification rule for attorneys). This means the collaborative process you get in Virginia has some legal teeth and consistency. For example, the code makes clear that anything said in a collaborative negotiation is confidential and generally can’t be used in court later if the collaboration fails – so people feel freer to negotiate without worrying that an offhand concession will be used against them in litigation.

Why Choose Collaborative? There are several potential benefits:

- You keep control: Instead of a judge (a stranger) making decisions, you and your spouse craft the agreement. This often leads to more customized solutions. I’ve seen collaborative couples agree to creative custody schedules or financial arrangements that a court might not have ordered but that work better for their family.

- Preserve relationships: Collaborative divorce strives to minimize hostility. The very act of sitting together to problem-solve can improve post-divorce co-parenting relationships, or at least keep them civil. Especially if you have kids, this is golden. By contrast, a nasty court fight can permanently damage any chance of amicable co-parenting. One client in Alexandria told me the collaborative process helped her see her husband not as an “enemy” but as a partner in transitioning their family – a perspective that would have been hard to find in a courtroom battle.

- Emotional support: The inclusion of coaches or therapists means you have support for the emotional side of divorce, not just the legal. Collaborative meetings can get tense (it’s still divorce), but coaches can intervene in the moment to calm things or to help one of you articulate feelings in a constructive way. This tends to make the process feel more humane.

- Privacy: Everything is handled in private meetings. Financial and personal details aren’t filed in public records (until the final agreement, and even then, sensitive info can sometimes be kept out of the court file). High-profile individuals and ordinary people alike appreciate that their dirty laundry won’t be aired in court filings.

- Potential cost and speed: Collaborative divorce can be faster and cheaper than litigation if it works. You’re avoiding multiple court hearings and the costly discovery process. That said, it’s not guaranteed to be cheaper – you are paying potentially for several professionals (lawyers + neutrals) by the hour, and if you have many meetings, it can add up. But in my experience, even when collaborative cases involve significant up-front cost, they often still beat the cost of protracted litigation which might involve motions, court waiting time, trial prep, etc. Plus, you’re “investing” in a resolution rather than throwing money into fighting.

The Big Risk: The elephant in the room is: What if it fails? If you don’t reach a full agreement, the collaborative process terminates and, as noted, both attorneys must withdraw. You then have to start over with litigation, new lawyers, etc., which can be costly. This is the biggest deterrent for some people considering collaborative divorce. It’s true that this is a risk – you could spend time and money in collaboration and end up with no agreement. However, in my practice, failure is the exception, not the norm, when both parties are genuinely committed to the process. The initial screening by collaborative lawyers is important; we typically assess whether both spouses seem able to negotiate in good faith. If one spouse is hiding assets or is hell-bent on revenge, collaborative may not be appropriate. There’s also an “out” in collaborative: either party can quit at any time if they feel it’s not working (it’s voluntary throughout). So you’re not trapped in it, but if you exit, it triggers the withdrawal rule.

Example: I facilitated a collaborative divorce for a couple from Falls Church. They had been married 15 years and had two middle-school kids. They both were professionals with busy careers, and they wanted to minimize disruption for the kids and themselves. In our collaborative meetings, we tackled parenting plans first – with help from a child specialist who provided insight into how the kids were coping. We came up with a creative arrangement where the parents alternated weekly custody but had a mid-week family dinner together every other week (this was something they came up with to maintain a sense of family unity post-divorce – not an idea that would easily come out of litigation). For finances, a neutral financial planner helped outline options for dividing their assets in a tax-efficient way and even projected future budgets so that both could maintain similar standards of living. There were moments of tension – like discussing one spouse’s spending habits – but the collaborative coaches helped them communicate these concerns without blowing up. After about four joint meetings over two months, we reached a comprehensive settlement. The final agreement was then drafted and, with both parties’ approval, submitted to the court along with the uncontested no-fault divorce paperwork. Neither had to appear in court; the divorce was finalized quietly. Both clients later told me that while divorce is never “fun,” the collaborative approach made them feel heard and respected, and most importantly, their kids saw that mom and dad could still work together, which set the stage for cooperative co-parenting.

Legal Note: When the agreement is done, it is typically incorporated into the final divorce decree. If a collaborative case partially settles and then goes to court for one issue, the same rule applies: the collaborative attorneys are out, but the agreements on other issues can often be preserved (for example, you agreed on property division but not on custody, you might only litigate custody). Virginia’s collaborative law statute also ensures that any admissions or communications made during collaboration are confidential and cannot be used in court, which encourages open dialogue.

Is Collaborative Right for You? If both you and your spouse are willing to actively participate in problem-solving and you trust each other enough to be honest (even if you’re angry or hurt), collaborative is worth considering. It works best when there’s a moderate level of trust and a genuine desire to avoid harming each other – even if you disagree on specifics. It’s not well-suited if one spouse is extremely adversarial, secretive, or unwilling to see the other’s point of view at all. Also, if there’s domestic violence or a significant power imbalance (one spouse always dominated the other), a court process might better protect the weaker party’s interests, because collaboration relies on voluntary fairness.

In Northern Virginia, we have many resources for collaborative divorce, including attorneys like me who are trained in the method. Always ensure any lawyer you consider for this has collaborative training. I find it a rewarding process – seeing a couple move from anger to a workable peace is a success that goes beyond just winning a legal case; it’s helping a family reorganize in a healthy way.

Next, we’ll talk about another alternative to court that’s somewhat less formal – mediation – which can be used in conjunction with any divorce path, contested or uncontested.

Chapter 7: Mediated Divorce

Mediation is another popular alternative to litigation, and it can be used in almost any divorce scenario – whether you’re amicable or barely able to speak, whether you have a simple case or complex assets. In mediation, a neutral third party (the mediator) facilitates discussions between you and your spouse to help you reach a settlement. Unlike collaborative divorce, in mediation, you may not both have lawyers present during the talks (though you can), and the mediator doesn’t represent either of you or make decisions – they guide you toward your own agreements. I often recommend mediation to clients in Northern Virginia, either as a primary approach or as a strategy to resolve specific sticking points in a contested case.

How Mediation Works: You and your spouse choose a mediator – usually a trained professional in dispute resolution, often a lawyer or therapist by background with mediation certification. Mediation sessions can be just you and the mediator, or you can have your lawyers present (this is called “attorney-assisted mediation”). You might all sit in the same room, or if things are tense, the mediator might shuttle between you in separate rooms (this is called caucus mediation, often used if there’s high conflict). The process is very flexible.

The mediator will start by establishing ground rules (e.g., be respectful, let each other speak, and maintain confidentiality) and by identifying the issues to be resolved – typically property division, support, and child-related matters. Then, you’ll work through each issue, with the mediator helping you communicate offers and understand each other’s interests. A good mediator doesn’t take sides but makes sure both voices are heard. They might offer creative suggestions or reframe what someone said to reduce tension. For example, in a mediation I was involved in for a Fairfax couple, the spouses kept clashing on how to split a retirement account. The mediator rephrased one’s position from “She just wants to take my money” to “I hear that financial security in retirement is very important to you, and you want to ensure you each have a fair share of the savings.” This reframing helped the other spouse avoid feeling attacked, and they eventually agreed to a roughly equal split with some adjustments.

The Lawyer’s Role: In mediation, your mediator is not your lawyer. They cannot give you individual legal advice (in fact, if the mediator is a lawyer, they must be careful not to give legal advice, only to facilitate). So, where do lawyers fit in? Many people consult with a lawyer outside the mediation sessions – maybe before mediation to understand their rights, or in between sessions to discuss proposals, and certainly at the end to review any draft agreement the mediation produces. Some folks have their attorney on standby by phone during a mediation session if needed. As mentioned, sometimes both parties bring lawyers to the mediation sessions, which can be helpful if you need real-time legal counsel during negotiations (though that increases costs).

In my practice, I often serve as a review attorney for a client who is mediating. They’ll go to mediation sessions on their own (or with minimal attorney involvement) and, once they reach a tentative deal, I’ll review the mediated agreement or memorandum of understanding. I might spot issues they didn’t consider or ensure the language properly protects my client. Usually, mediated agreements are reached in principle, and then lawyers formalize them into a property settlement agreement for filing in court.

Court-Connected Mediation: Virginia courts encourage mediation, particularly for child custody and visitation issues. We saw earlier that Virginia law actually requires judges to refer disputing parents to a dispute resolution orientation session (basically a mediation intro) in any appropriate case (and definitely if custody is contested, barring any abuse issues) (Va. Code Ann. § 20-124.4, 2026). In Northern Virginia, for example, the Fairfax County Circuit Court and the Juvenile & Domestic Relations (J&DR) Courts have lists of approved family mediators. Sometimes the first session or orientation is free (paid by the court). It’s an opportunity for couples to learn about mediation and maybe try a short session. Participation beyond the orientation is voluntary – both have to agree to continue mediating. In my experience, even high-conflict couples will often give mediation a shot when a judge strongly suggests it – and many are surprised when they manage to settle some or all issues.

Benefits of Mediation:

- You are in charge: Like collaborative law, mediation keeps decision-making in the hands of the spouses, not a judge. The mediator doesn’t impose a solution; you two craft it. This often leads to more tailored agreements that you’re both willing to follow.

- Cost-effective: Mediation can be cheaper than litigation because you might resolve issues in a few sessions instead of in court motions and trials. A mediator might charge a few hundred dollars an hour, but if you split that cost and only need, say, 5–6 hours to reach agreement on major points, that’s often far less than each of you paying attorneys to fight in court.

- Faster: You can schedule mediation as soon as both agree to it – you’re not waiting for court dates. Some of my clients have resolved everything in mediation in a matter of weeks (plus whatever separation waiting period the law requires for the final divorce). Courts, on the other hand, move slowly.

- Preserves relationships: Mediation, even more so than collaborative approaches, can sometimes mend communication issues. It forces you to sit in the room (literally or figuratively) and talk. For co-parents, this is a chance to begin the shift from married partners to co-parenting partners. Learning to discuss and compromise in mediation sets a tone for future interactions.

- Flexibility: Mediation can address any issue you want. Want to figure out how to handle who pays for the child’s college in 10 years (something courts generally can’t order in Virginia)? You can mediate that. Want to include how you’ll divide time with the family dog? Mediate it. The process is informal, so you can be creative and include personal priorities that a court might not consider.

- Confidentiality: Mediation discussions are confidential by law (they generally can’t be used as evidence if you later go to trial, and mediators can’t be forced to testify about what was said). This encourages open dialogue and risk-taking in offers. If you propose a compromise, it won’t haunt you later in court as an “admission.” The Virginia code has provisions that protect the confidentiality of mediation communications (except certain things like threats or ongoing abuse, of course).

Challenges of Mediation:

- It requires a certain degree of cooperation or at least a willingness to try. If one spouse simply refuses to negotiate or is stonewalling, mediation won’t magically fix that.

- A mediator can’t compel disclosure. If you suspect your spouse is hiding assets, a mediator doesn’t have subpoena power. In such a case, you might need some litigation tools (or at least attorney help) alongside mediation to ensure financial transparency.

- There’s a risk of imbalance. If one spouse is much more dominant or knowledgeable about finances, the other could be at a disadvantage. A good mediator will recognize power imbalances and try to level the field (for example, by ensuring both have access to financial advice). As a lawyer, I sometimes empower a weaker party by coaching them before sessions or being present if needed. And remember, any agreement can be reviewed by your lawyer before you sign – so you have a safeguard.

Example: A couple in Prince William County had been arguing for months and had gotten nowhere in dividing their assets (they owned a house, some retirement accounts, and one spouse had a small business). They decided to try mediation with a retired judge as the mediator. In the first session, things were tense – they had a lot of resentment. The mediator patiently let each vent a bit and then refocused them on their common goal: getting through this and moving on with life. Over three sessions, they hammered out a deal: the wife would keep the marital home and refinance it in her name (giving the husband a $50,000 payout for his share of equity), and the husband would keep his business and a larger share of his 401(k) since the wife got the house equity. They also agreed on a spousal support amount for a few years to help the wife transition (she had stopped working during the marriage). When they hit a snag with the support number, the mediator proposed a formula based on Virginia’s spousal support guidelines as a starting point, which helped because it felt more objective. They gave themselves a range and settled in the middle. They wrote up a memorandum of understanding. I then helped the wife incorporate that into a formal settlement agreement and obtained an uncontested no-fault divorce through the court. Neither had to publicly air their grievances in the trial, and both felt the outcome was fair.

Mediation and Local Courts: Northern Virginia courts strongly encourage settlements. In Fairfax, for example, if you set a trial date, the court will often ask if you’ve tried mediation. They even have a day-of-trial settlement conference system with neutral attorneys or retired judges (like mediation) to give one last shot at settling before trial. I had a Loudoun case where on the morning of trial the judge sent us and the other side into a room with a neutral attorney for two hours – and we did settle, avoiding the need for the judge to decide. That’s how much courts prefer parties to reach their own agreements.

Voluntary, but…: Mediation is voluntary – you both have to agree to do it (except for attending that initial orientation if ordered). You can also quit mediation at any time if it’s not productive. There’s no binding result unless/until you sign a final agreement. Some people worry “what if we can’t agree?” Then you simply stop mediating and proceed with litigation or another method. Nothing lost except maybe some time and mediation fees, but usually you gain clarity on the issues, even if you don’t fully settle.

Combination with Other Paths: Mediation often intersects with other approaches. For example, you might have a contested, fault-based case, but still mediate property division. Or you might be doing collaborative divorce but use a mediator for a specific dispute within that. It’s not an either/or. Mediation is a tool that can be used to supplement many situations.

In conclusion, mediation is a flexible and effective way for many couples to resolve divorce issues on their own terms. It requires willingness to negotiate and compromise, but it can save significant heartache and expense. I always tell clients: At least give it a shot. You might be surprised at how far you can get with the right neutral guiding the conversation.

Next, we’ll cover “summary” or simplified divorces – essentially, the scenario where your case is so straightforward that the process can be even more streamlined.

Chapter 8: Summary (Simplified) Divorce

Clients sometimes ask, “Is there such a thing as a quick divorce in Virginia? I heard about ‘summary divorce’ in other states.” While Virginia doesn’t have an official “summary divorce,” we do have ways to simplify the process if certain conditions are met. Essentially, a summary or simplified divorce is an uncontested, no-fault divorce in a simple situation – often a shorter marriage with no kids and minimal assets – where the couple meets the criteria to use the fastest available procedures. If that describes your case, you’re in luck: your divorce can be relatively quick and painless (at least from a legal standpoint).

Qualifying for a Simplified Divorce: Common features of cases that proceed in a very streamlined way include:

- Short Marriage Duration: Generally, the shorter the marriage, the fewer entanglements (though not always). A couple married 2 years with no real estate and no children is a prime candidate for a quick divorce. There’s just less to sort out compared to, say, a 20-year marriage.

- No Minor Children: Kids add complexity (custody, support, visitation). If you don’t have children together, you eliminate those issues. Moreover, as we discussed, no kids + a settlement agreement allows the shorter 6-month separation period for no-fault divorce. That alone cuts the wait time in half.

- Limited Assets and Debts: If you’ve kept finances relatively separate, or you rent and have no real property, dividing things is easier. Maybe you each keep your own car and bank accounts, and there’s no jointly owned house or significant investments. Fewer assets to divide usually means fewer potential disputes.

- Agreement on Everything: Like an uncontested divorce. Even if you have some assets, if you already agreed who gets what, you won’t need court intervention. A simplified case is typically one in which a comprehensive settlement is reached very quickly, or even before filing for divorce.

- No Need for Ongoing Support: If neither spouse is seeking alimony (spousal support) and both are self-sufficient (or the support issue is minor and agreed upon), that removes another potential roadblock. Alimony fights can complicate divorces; their absence simplifies things.

When these factors are present, your divorce process essentially becomes an administrative exercise: file the right papers, wait out the clock (if not already done), and get your decree.

Procedural Shortcuts: Virginia law allows a few shortcuts in simple, uncontested cases:

- Affidavit/Deposition instead of Court Hearing: We touched on this earlier – Va. Code § 20-106 allows uncontested no-fault divorces to be proven by affidavit or deposition, without a court hearing, if certain conditions are met (e.g., a signed settlement agreement and no issues other than the divorce). In a simplified case, you’ll almost always use this option. It means once your paperwork is filed, you might only have to submit an affidavit from one of you (and possibly a witness, though as noted, just the party’s affidavit is often enough now) attesting to the facts of the separation and residency. The judge can then sign off on the divorce at their desk. You may never have to go to the courthouse at all. This is a huge simplifier – imagine you could literally mail in your divorce (through filings) and get back a final order in the mail weeks later. Many Northern Virginia courts routinely process affidavit divorces.

- Waiver of Service/Answer: In a truly uncontested case, the defendant spouse can sign a form called an “Acceptance/Waiver of Service” which means they officially acknowledge receipt of the divorce complaint and waive formal service by a sheriff or process server. They can also waive the notice of any hearing. This spares the need for formal service and speeds things up. Similarly, instead of an extensive Answer, sometimes the spouse will just sign the settlement and perhaps a form indicating they don’t contest anything. In Fairfax, for example, there’s a form for the defendant to waive further notice and consent to the case being heard immediately after the requisite time has passed.

- Scheduling: Some courts have a fast track for uncontested divorces. In a simple case, the moment you hit your six-month or one-year mark, you can immediately submit the final documents. As one Virginia attorney humorously puts it, a no-fault divorce is often more about waiting than doing. Once the wait is over, the doing part is quick. I recall a Frederick County case where the couple literally went to the courthouse on the first day after their one-year separation, filed the complaint with an attached signed agreement, and by the next week we arranged an ore tenus hearing (they chose to do it in person) and they were divorced that day. It helped that it was a small county with a light docket – in Fairfax, you might not get a hearing that fast – but by affidavit it could still be within a few weeks.

Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Divorce: Simplified cases are often handled without extensive involvement from a lawyer. Virginia even provides resources for DIY divorces. For example, VaLegalAid.org offers an online questionnaire that can help fill out forms for an uncontested divorce, and some localities offer pro se divorce packets (e.g., the Fairfax County pro se packet). In a really straightforward case (no kids, few assets), I’ve seen people successfully navigate the system on their own. They might consult an attorney just to check the settlement or forms, but they don’t necessarily need full representation. The court clerks also sometimes have guidance (they can’t give legal advice, but they can often point you to instructions). It’s important to follow details carefully – I’ve also seen DIY filers get tripped up by technicalities (like not properly wording the residency affidavit, or forgetting to include a form). But the point is, Virginia’s uncontested process is manageable for ordinary folks, especially if the case is simple.

Cost and Time: A summary-type divorce is the least expensive in terms of legal costs. Filing fees in Virginia are a few hundred dollars at most (usually around $86 to file a divorce, plus maybe $20 for service if you use a sheriff). If you don’t use lawyers much, your out-of-pocket might just be that. If you use a lawyer to draft or review an agreement, that could be a flat fee or a few hours of time. It’s not uncommon for a fully agreed, simple divorce to cost under $1,000 total in legal expenses – some even just a few hundred (aside from any filing fees). Time-wise, once the waiting period is done, the rest can happen quickly. Some Virginia family law firms advertise “fast divorce” services specifically aimed at these scenarios, boasting final orders in hand just weeks after filing (and it’s true, I’ve seen final decrees come back in as little as 2–3 weeks in some uncontested cases in Arlington and Alexandria).

Example: Consider a young couple in Arlington who married in their early 20s, had no kids, rented an apartment, and after 3 years decided to part ways amicably. They separate, one moves out. They split their few joint belongings privately (no lawyers needed for that – they just agreed who keeps the couch, the one car they owned was in one’s name already, etc.). They have no real estate, no shared bank accounts beyond maybe a security deposit to split. Neither needs spousal support because both are working and self-sufficient. They document their separation in a simple one-page agreement that basically states, “We’ve agreed on how to handle our property and neither will claim support.” Six months later (since no kids), the husband files for divorce on no-fault grounds, attaching that agreement. The wife signs a waiver accepting service and agreeing the case can be heard without further notice. The husband prepares an affidavit swearing to the facts (the date of marriage, the date of separation, residency, that they have no kids, and that they’ve agreed on everything). He also has a co-worker friend sign a short affidavit confirming “Yes, I know them and know they’ve lived apart for over six months and intended to end the marriage.” These are filed with a proposed final decree that both spouses have signed off on. A judge reviews the file in chambers and signs the decree. They get copies mailed to them. Divorce complete – neither ever had to go to court or see a judge. From filing to finish, maybe 4 weeks passed. This is essentially a summary divorce in practice.

Caution: If something seems too easy, make sure you haven’t overlooked anything. Sometimes couples think they have nothing to sort out, but forget about retirement accounts or a small joint debt. Even in a friendly split, it’s wise to do a quick inventory of assets and liabilities and ensure your agreement or understanding covers them. A simplified divorce can hit a snag if, say, the judge notices the complaint didn’t mention a piece of real estate (maybe acquired before marriage but titled jointly, for example). Usually, in a simple case, there truly isn’t anything big, but double-checking avoids issues.

Also, even in a simple divorce, legal requirements still strictly apply. For instance, the 6-month/1-year rule is absolute – there’s no skipping that (unless you go the fault route like adultery, but then it’s not “simplified” anymore). And the 6-month separation w/ agreement only counts if you indeed have no minor children of the marriage. If either of you is pregnant or you have a child together under 18, you must do the full year. I’ve had someone ask, “Our baby is due next month, can we do the 6-month thing before it’s born?” Unfortunately, no – the presence of a minor child triggers the 1-year requirement, even if the child wasn’t born at the time of separation. So a couple expecting a child, or with a baby, cannot fast-track under the six-month rule.

Default Divorce as Simplified Divorce: Another scenario: a default divorce (where one spouse doesn’t participate at all) can be relatively simple. If you file and the other party never responds or shows up, after the required time and proper service, you can often get a divorce by default judgment. You still have to present evidence of the separation, etc., but that too can often be done by affidavit now. Default cases can be quick if you know where the spouse is to serve them (or they’ve disappeared and you proceed by order of publication, which takes longer). I mention this because I’ve had a case in Fairfax where the husband left the state and ghosted my client. She waited the one-year separation, we served him by publication (since he was nowhere to be found), and then she gave a brief testimony in court to get the divorce. He wasn’t there to contest anything, so it was granted – that was “simplified” in that only one side was involved. Default isn’t ideal (because it means one person might later say they didn’t know about the divorce), but it is an available route if a spouse is unresponsive.

Post-Divorce Simplicity: In a simplified divorce, because there were few entanglements, life after divorce is cleaner too. There might not be any ongoing obligations like child support or alimony, and no property transfers to enforce. It’s basically each goes their separate way with a clean break. This is the scenario where the divorce decree is often just a few pages long, dissolving the marriage and maybe incorporating a short agreement. I’ve seen final orders that just say “marriage dissolved, parties to comply with their agreement attached” and not much else – because nothing else was needed.

To sum up, a “summary” divorce in Virginia is essentially an uncontested, no-fault divorce with a streamlined process because the case is simple. If you and your spouse qualify for this kind of approach, consider yourselves fortunate in an otherwise unfortunate situation – you can move through the legal part of divorce relatively quickly and focus on the emotional healing and future plans. Always ensure all legal boxes are ticked, but know that the courts have mechanisms to expedite cases like yours.

Now that we’ve covered all these divorce types and processes, it’s time to put it all together. In the next chapter, I’ll walk you through the step-by-step Virginia divorce process, touching on how the above elements come into play from start to finish.

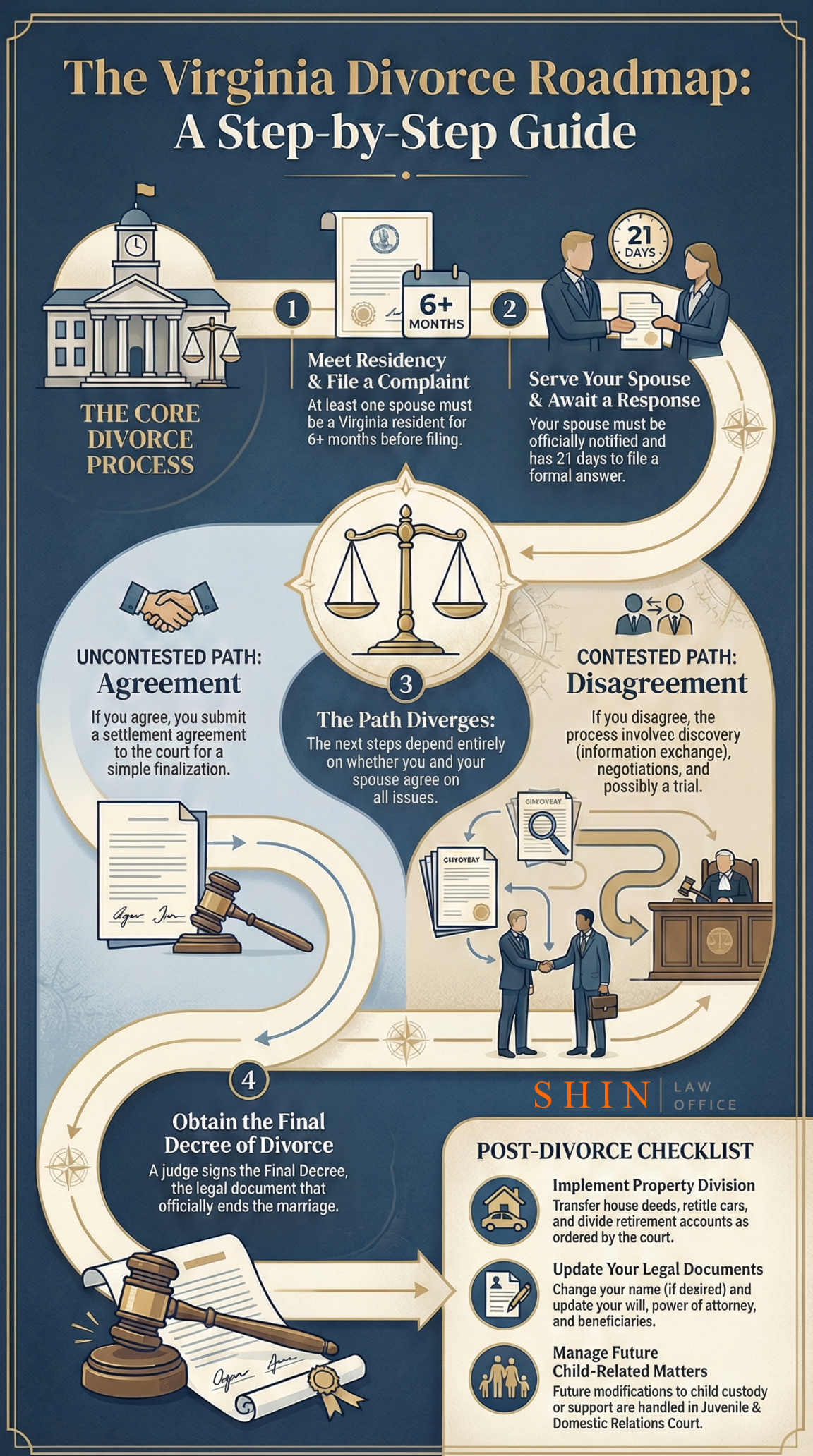

Chapter 9: Virginia Divorce Process Step-by-Step

No matter what type of divorce path you choose (uncontested, mediated, contested, etc.), every divorce in Virginia follows the same general legal roadmap. Think of this as the Divorce Journey – the specific scenery might differ (collaborative conference room vs. courthouse, amicable chats vs. heated debates), but the checkpoints along the way are consistent. In this chapter, I’ll outline the step-by-step process for a Virginia divorce from start to finish, with practical insights for residents of Northern Virginia counties.