Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

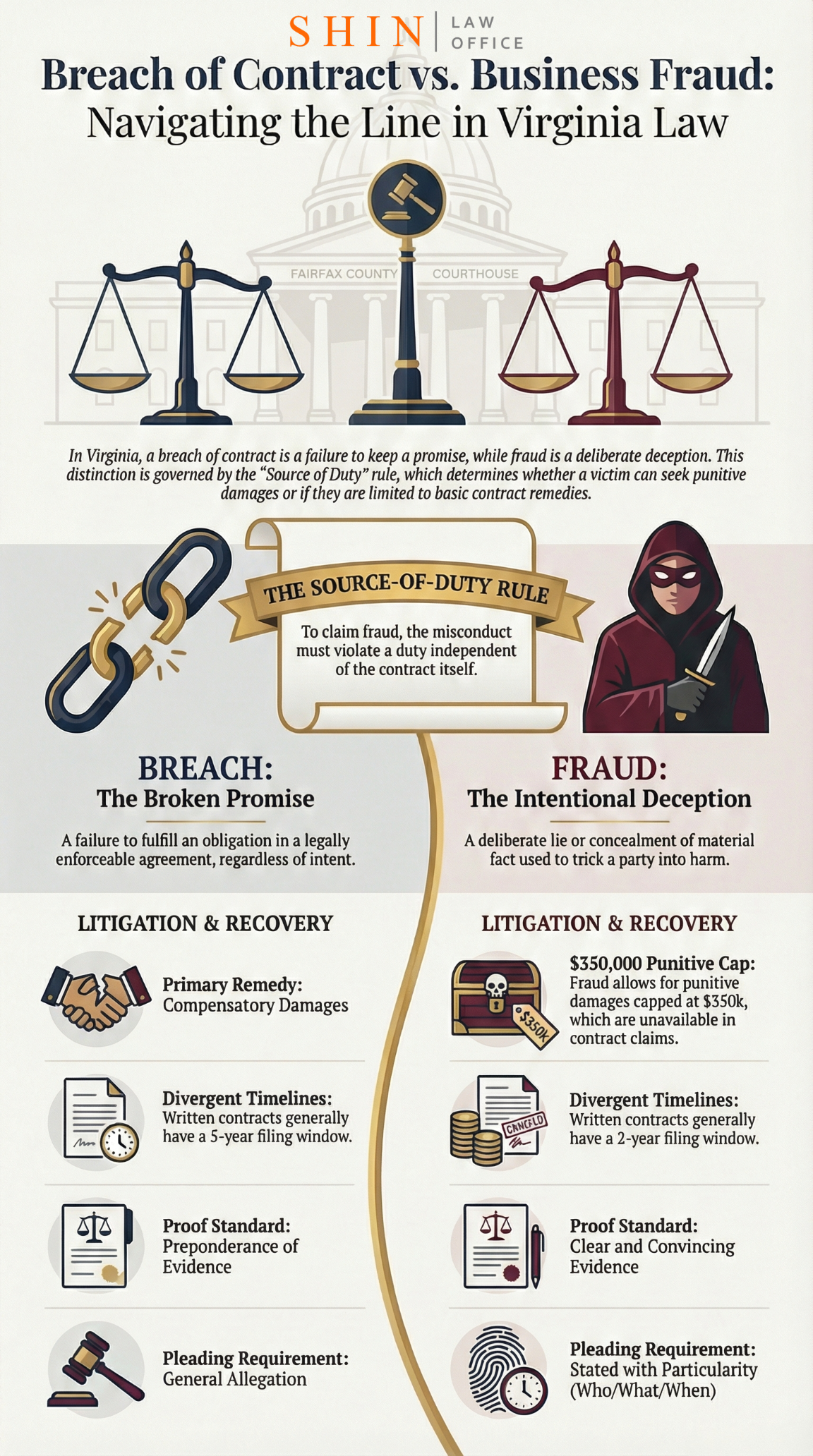

As a business attorney in Fairfax County, I’ll tell you the key difference plainly: a breach of contract is when someone fails to fulfill a promise in an agreement, whereas business fraud involves a deliberate lie or concealment of a fact that causes harm, separate from the contract itself. This distinction matters because Virginia law (and our Fairfax courts) treat these cases very differently – fraud is harder to prove but can lead to punitive damages and other remedies that a simple contract claim cannot. In short, not every broken promise constitutes fraud, and labeling a contract dispute as “fraud” when it’s not can lead to early dismissal of the claim. Knowing the difference helps business owners pursue the right legal strategy in Fairfax County’s courts.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Understanding the Legal Basics of Contracts

Chapter 2: What Constitutes Business Fraud in Virginia

Chapter 3: How Misrepresentation and Concealment Turn a Contract Breach into a Tort

Chapter 4: Why This Distinction Matters in Fairfax County Courts

Chapter 5: Practical Examples from Real-World Disputes

Chapter 6: What Business Owners Should Do if They Suspect Fraud

References

Chapter 1: Understanding the Legal Basics of Contracts

I’m a Fairfax County attorney, and I’ve seen firsthand how a breach of contract can throw a business into turmoil. Let’s start with the basics: a contract is a legally enforceable agreement – essentially, a set of promises the law will uphold. When two businesses (or individuals) make a deal – whether it’s a signed vendor agreement or a handshake on a service – each side takes on obligations. Breach of contract means one party failed to fulfill their end of the bargain or interfered with the other’s performance. This sounds straightforward, but breaches come in many forms and degrees. Virginia law (which Fairfax County courts follow) expects parties to honor the exact terms of their agreement.

To sue for breach of contract in Virginia, you generally must prove three things: (1) a valid contract existed (with a clear offer, acceptance, and something of value exchanged), (2) the other party broke a promise or obligation under that contract, and (3) you suffered harm or damages because of that breach. For example, if a tech supplier in Tysons agrees in writing to deliver software by July 1 and fails to do so, that’s a breach – you didn’t get what was promised. Virginia courts will enforce contracts as written, and Fairfax judges are known to read the fine print and hold parties to their agreed terms. Importantly, a breach does not require proving ill intent – even an honest mistake or unforeseen issue can constitute a breach if it violates the contract.

Not all breaches are equal. Some are minor slip-ups, others are material failures. A minor breach might be a slight delay or a trivial deviation that doesn’t defeat the contract’s main purpose, meaning you might still have to uphold your end though you can claim any small damages. A material breach is a serious failure that goes to the heart of the deal, freeing the non-breaching party from further obligations and entitling them to seek full damages. For instance, if you hired a contractor to build an office space in Fairfax and they never show up, that’s material – you can terminate the contract and seek compensation for the loss. Virginia follows the “first material breach” rule: a party that commits a material breach can’t enforce the contract against the other side.

Remedies for breach aim to make the injured party whole as if the contract had been fulfilled. Typically, you can recover compensatory damages for direct losses (e.g. payments you made for nothing, or the cost difference to get a replacement deal) and sometimes consequential damages for downstream losses that were foreseeable (say you lost clients because the product wasn’t delivered). What you generally cannot get for a pure breach of contract in Virginia is punitive damages – the law doesn’t punish breaching a contract, because a breach isn’t a crime or an independent tort by itself. So even if you feel wronged or suspect the breach was done in bad faith, you won’t get “punishment” money or your attorney’s fees for a simple breach (unless the contract explicitly allows fee-shifting). This is why we need to examine whether a case is just breach or something more malicious like fraud – the classification affects your strategy and potential recovery.

Contracts are the backbone of everyday business in Northern Virginia. From a Vienna shop owner who paid a contractor for renovations that never finished to a startup in Reston dealing with a client who won’t pay invoices, I empathize with clients facing broken deals. The good news is the legal system provides remedies to the wronged party. But pursuing those remedies can be daunting – especially if you’re not sure whether the wrong is just a breach of contract or crosses into fraud. In the next chapters, I’ll clarify how Virginia law (and Fairfax courts) define business fraud and how deceitful conduct can turn what appears to be a breach of contract into a tort claim.

Chapter 2: What Constitutes Business Fraud in Virginia

Business fraud is a game-changer in a legal dispute. Unlike breach of contract, which simply violates a promise between the parties, fraud is a tort – a civil wrong based on a violation of common law duty not to deceive. In plain English, fraud means one party lied or concealed a material fact, with the intent to trick the other party, and that lie caused damage. Virginia courts have well-established elements that you must prove to succeed on a fraud claim:

- False Representation: The defendant made a false statement of present or past fact. It can also include hiding or concealing a fact when there was a duty to speak.

- Material Fact: The false statement was about something material – an important fact that a reasonable person would rely on in making a decision. Trivial misstatements won’t meet this bar.

- Knowledge of Falsity: The person making the statement knew it was false, or at least made it with reckless disregard for the truth (in the case of actual fraud). In other words, it wasn’t an innocent mistake.

- Intent to Mislead: They made the misrepresentation intentionally, specifically to induce the other party to rely on it. This is the fraudulent intent – essentially, a scheme to trick you.

- Reliance: The victim (plaintiff) actually relied on the false statement, and their reliance was reasonable under the circumstances. You have to show you were influenced by the lie – e.g. you entered the contract or transaction because of what was misrepresented.

- Resulting Damage: The falsehood caused you measurable harm. This could be financial loss or other detriment. No harm, no fraud claim – even if a lie was told.

Virginia’s Supreme Court has reiterated this six-part test many times, such as in Evaluation Research Corp. v. Alequin (1994). All six elements must be proven; miss one and the fraud claim fails. Additionally, fraud must be proven by “clear and convincing” evidence, a higher standard than the preponderance of the evidence in civil cases. The idea is that accusing someone of fraud is serious, so the proof must be strong and specific.

A few important nuances for business owners to grasp: (a) The misrepresentation generally must be about a present or pre-existing fact, not just a promise of future action. If someone makes a promise and simply doesn’t keep it, that alone is not fraud – it’s a breach of contract. For example, if your vendor promises to deliver goods by December and fails to do so, that constitutes a breach. It becomes fraud only if you can show that, at the time the promise was made, the vendor never intended to deliver on time (meaning the promise was a lie at the time it was made). Virginia courts are clear: a broken promise or prediction isn’t fraud unless there was present deceptive intent. This is often called promissory fraud, and it’s difficult to prove without a “smoking gun” (such as an email in which the vendor admitted they never intended to perform). (b) Silence or nondisclosure constitutes fraud only if there is a duty to disclose. In arm’s-length business deals, neither party is required to disclose all information, but if one party actively conceals a material fact or speaks half-truths to mislead, that can constitute fraud. For instance, if a seller knows a building has a serious hidden defect and conceals it to sell at a higher price, that concealment could constitute fraud, because a reasonable buyer would expect such a material problem to be disclosed.

Because fraud allegations are so potent (they open the door to punitive damages and tarnish the defendant’s character), Virginia courts apply strict pleading standards. Our courts require that fraud be pleaded “with particularity”. This means if you file a lawsuit claiming fraud, your complaint must spell out the details: who said what, when and where they said it, what exactly was false about the statement, and how you relied on it. General accusations like “the defendant lied about the contract” will get kicked out – Fairfax judges routinely sustain demurrers (motions to dismiss) if a fraud count is vague or just mirrors a breach of contract claim. In my practice, I take great care to investigate and plead fraud claims with precision, or else risk losing them early. It’s a double-edged sword: a well-founded fraud claim can dramatically increase your leverage in a dispute, but a flimsy one can undermine your credibility.

In sum, business fraud in Virginia means intentional deception that’s independent of the contract itself. It carries the potential for additional remedies – like punitive damages (which are capped at $350,000 by statute) and even rescission of the contract – but it also comes with higher stakes in proof and pleading. Next, we’ll explore how certain misrepresentations or concealment can transform an ordinary contract breach case into a fraud case (and when they can’t).

Chapter 3: How Misrepresentation and Concealment Turn a Contract Breach into a Tort

One of the most common questions I get is: “Can I sue for fraud and breach of contract together?” The answer is yes, but only under specific circumstances. Virginia law draws a line to prevent every breach of contract from being dressed up as a fraud claim. The legal test turns on the “source of duty” rule: to have a tort (fraud) claim alongside a contract claim, the falsehood or misconduct must violate a duty that exists independently of the contract. If the only duty breached is the promise made in the contract itself, then your remedy lies in contract law, not tort.

Misrepresentations made during contract negotiations – before the contract is signed – are the classic example of an independent duty. Every party has a general duty not to commit fraud to induce someone into an agreement. So if someone lies about a material fact to get you to enter the deal, that duty to be truthful exists outside the contract. In that scenario, you can sue for breach of contract and for fraud (fraud in the inducement). For instance, imagine a Fairfax business is selling a commercial property and tells the buyer “our building’s occupancy rate is 95%” when in reality half the building is vacant. If the buyer relies on that lie and signs the contract, the seller has breached the contract if the representations are written into the agreement, but more importantly, the seller also violated a common-law duty not to deceive – which is a fraud tort. The Virginia Supreme Court has upheld fraud claims in such cases: fraudulent inducement is actionable because the fraud occurred independently of the performance of the contract obligations. In Station #2, LLC v. Lynch (2010), for example, the court permitted a fraudulent inducement claim to proceed alongside a breach-of-contract claim when a party was alleged to have misrepresented facts before the contract was formed. Similarly, in Abi-Najm v. Concord Condo. (Va. 2010), condo buyers were allowed to sue the developer for fraud where the developer had misrepresented an existing fact (the quality of materials) to get them to sign – even though those matters were later covered in the contract. The courts made clear that a lie aimed to induce the agreement, about something real in the present, can give rise to a tort claim because it’s not simply a broken contractual promise, it’s a scheme to defraud.

Concealment can play a similar role. If one party actively conceals a vital fact during negotiations – say, a franchise seller hides that their financial statements were inflated or fails to disclose a pending lawsuit that would affect the business – that concealment, if done to trick the other side into the deal, may be treated as fraud. Virginia law recognizes fraud by omission when the concealing party has a duty to speak (for instance, if they made a partial disclosure that was misleading, or if the parties had a relationship that gives rise to a duty). The key is that the concealment must be intentional and material to be actionable. I always tell clients: if the other side lied or concealed information to get you to sign, that’s more than just a breach later – it’s fraud at the formation stage.

On the other hand, misrepresentations made after the contract is in place, about how the contract is being performed, usually do not give rise to a fraud claim if they are closely tied to the contract duties. The Supreme Court of Virginia drove this point home in Dunn Construction Co. v. Cloney (2009). In that case, a homeowner contracted for construction work and the contractor did shoddy work on a foundation wall. After an inspection failed, the contractor lied in writing by “guaranteeing” the repairs were properly done (even claiming they put in steel rebar as required) to induce the owner to make final payment. The owner paid, later discovered the lie (the wall was not actually fixed), and sued for breach of contract and fraud, even winning punitive damages from a jury. But on appeal, the Virginia Supreme Court took away the fraud verdict, saying essentially: We don’t condone the contractor’s misrepresentation, but this is still not actionable fraud in addition to breach. Why? Because the contractor’s false statement was about the performance of the contract itself – the duty to build the wall properly was a contractual duty, not a separate common-law duty. The lie was told to get payment that was due under the contract; it was “entwined with the breach” and not an independent tort. In other words, the only thing the contractor did wrong was fail to do the work correctly (breach of contract) and then falsely claim he did (essentially covering up the breach) – that does not create a new duty outside the contract. The court was cautious: allowing fraud in every case where a breaching party misrepresents something would “turn every breach of contract into an actionable fraud”, which Virginia law forbids.

This illustrates the fine line: a misrepresentation “entwined with a breach” of the contract won’t support a fraud claim. Only when the misrepresentation concerns an extra-contractual matter – or breaches a duty that exists outside the contract – will it be treated as fraud. Virginia’s economic loss rule encapsulates this idea by barring recovery in tort for purely economic losses arising from contract duties. For example, if a software developer fails to deliver a functional product (breach of contract) and falsely assures you “it’s working great” just to delay you, that misrepresentation is about the contract performance and usually won’t give you a separate fraud claim. However, if that same developer lied before signing the contract by saying “our software meets all Department of Defense security specs” when it doesn’t, that lie induced the contract and could be fraud in the inducement.

In Virginia courts (including Fairfax), judges ask: “What duty did the defendant breach?” If the duty comes solely from the contract, the claim must be contract. If there’s a breach of a broader duty (like the duty not to defraud or to refrain from intentional misrepresentation), then a tort claim can go forward. The Supreme Court cemented this in Richmond Metropolitan Authority v. McDevitt Street Bovis, Inc. (1998), stating that to recover in tort, “the duty tortiously… breached must be a common law duty, not one existing between the parties solely by virtue of the contract”. That principle – sometimes called the source-of-duty rule – is cited often in Fairfax courtrooms. Judges here will scrutinize a complaint to determine whether a fraud count alleges an independent deception or merely restates a breach of contract. If it’s the latter, they will dismiss the fraud count on demurrer.

To sum up this chapter: misrepresentation or concealment can elevate a case from contract to tort only if it goes beyond the four corners of the contract. Lying to induce a contract (or actively hiding a key fact) violates a duty to negotiate in good faith and can be fraud. Simply failing to do what you promised, even with a flimsy excuse or a cover-up, usually remains a contract matter. This distinction can be subtle, but it’s absolutely crucial in deciding how to plead your case and what remedies you might recover.

Chapter 4: Why This Distinction Matters in Fairfax County Courts

You might be thinking, “Alright, I get the difference in theory – but what does it mean for me as a business owner litigating in Fairfax County?” It matters a great deal, both for legal strategy and outcomes. Fairfax County, being one of Virginia’s busiest commercial jurisdictions, sees its fair share of contract disputes and fraud allegations. Our local courts are well-versed in these nuances and are known for holding plaintiffs to the strict standards Virginia law requires.

Here are some concrete reasons why the breach vs. fraud distinction is so important in Fairfax:

- **Available Remedies and Damages: As mentioned, a breach of contract limits you to compensatory damages (and maybe interest or specific performance) but no punitive damages. If you can establish fraud, you open the door to punitive damages (capped at $350,000 in Virginia), which can dramatically increase the stakes for the defendant. Fraud can also support rescission of the contract – essentially unwinding the deal – or other equitable relief that a simple contract claim might not afford. In Fairfax courts, I’ve seen cases where adding a fraud count significantly increased settlement value because defendants worried about the unpredictability of jury awards of punitive damages. Additionally, Virginia’s statute of limitations differs: for written contracts, you generally have 5 years to sue (3 years for oral contracts), whereas fraud has a 2-year limit from when the fraud was or should have been discovered. This can be crucial. Suppose a breach of a long-term contract isn’t discovered until year 4 – the contract claim on a written contract might still be timely, but a fraud claim could be too late if more than 2 years have passed since you reasonably should have found the fraud. Conversely, in some cases the discovery rule for fraud might extend the time if the fraud was hidden. The timing can affect which claims you’re able to bring in Fairfax courts.

- Burden of Proof and Litigation Hurdles: If you plead fraud, be prepared for a tougher fight at the outset. Fairfax judges often see defendants file demurrers or motions to strike targeting fraud counts. They will closely examine whether your complaint details the fraud with the required particularity (the who, what, when, where, how). If you haven’t, that fraud count will likely be dismissed early. Also, because fraud must be proven by clear and convincing evidence, by the time you get to trial, a judge may remind the jury (or themselves, in a bench trial) of that higher bar. In practical terms, this means as a plaintiff you need to invest more in the fact-finding process (documents, forensic evidence, maybe expert witnesses) to build a convincing case of intentional deceit. It can mean higher litigation costs. I always discuss with clients whether the potential upside of a fraud claim (punitive damages, leverage) is worth the added complexity and scrutiny it brings.

- Credibility and Strategic Impact: In Fairfax, raising a fraud claim can send a strong signal – it essentially says “the other side didn’t just break a promise, they cheated.” This can put reputational pressure on a defendant, and as mentioned, increase their exposure. However, it can also backfire if done without basis. Judges here have little patience for embellishing a contract case with a flimsy fraud count. A weak fraud allegation might be thrown out, and that could undermine your credibility on the remaining contract claims. There’s also the psychological effect on juries: if both claims go to trial, jurors might wonder, “Was this a simple breach or were they actually dishonest?” It could influence how they view the evidence. But remember, if the fraud claim shouldn’t have been there in the first place, the judge won’t let it reach the jury. Fairfax Circuit Court judges are quick to demurrer out fraud or other tort claims that are improperly pled or lack an independent duty.

- Procedural and Court Considerations: Where you file and litigate can depend on the claims and amounts at issue. In Fairfax County General District Court (which handles claims up to $50,000), cases move quickly and there’s no jury and limited discovery. A straightforward breach of contract for $30k might go to GDC and get resolved in a bench trial within a few months. But if you layer on a fraud claim with a request for punitive damages, you’re likely pushing the case into Circuit Court (the higher court for unlimited claims and complex cases) for a jury trial and full discovery. Circuit Court in Fairfax is a more formal arena – pleadings are detailed, rules of evidence strictly applied, and the case can take a year or more to reach trial with depositions and motions along the way. Sometimes, keeping a dispute as a contract-only matter (if the amounts are modest) can be advantageous for speed and cost. Other times, the gravity of fraud and the larger damages involved demand a Circuit Court battle. Fairfax Circuit is known for its “rocket docket” in some cases but also for careful case management, especially with complex business disputes. The court will often issue scheduling orders and require a settlement conference or mediation for business cases. If fraud is in play, defendants might be more eager to settle early once the claim survives a demurrer, given the risks.

- Local Jury Perspectives: While every jury is different, Fairfax County jurors (drawn from a highly educated population in Northern Virginia) are generally well-suited to understand business disputes. In my experience, they take instructions seriously – including the notion that fraud needs clear and convincing proof. If a case truly involves deceitful conduct, jurors here don’t take kindly to liars and can award punitive damages (again, up to the cap). But if they sense a plaintiff is overreaching – painting a simple contract breach as fraud without solid evidence – that can lead to a loss of trust. It’s another reason to only assert fraud in good faith and with solid grounding.

Ultimately, the breach vs. fraud distinction in Fairfax County courts affects how I advise clients. If we have evidence of deceit (say, emails revealing the other side knew their statements were false), we’ll plead fraud confidently and use it to drive a harder bargain or seek punitive redress. If the dispute is more about a broken promise without indicia of a scheme, we’ll likely stick to contract claims to keep the case streamlined and credible. The local courts encourage this strategic clarity: they reward precise, well-founded claims and will weed out the rest.

Understanding this landscape means you, as a business owner, can appreciate why your attorney might recommend one path over another. It’s about maximizing your chances of recovery while avoiding pitfalls that could weaken your position in Fairfax’s legal forum.

Chapter 5: Practical Examples from Real-World Disputes

Sometimes the best way to grasp these concepts is through real-life (or realistic) examples. Let’s walk through a few scenarios that illustrate when a business dispute stays a breach of contract and when it escalates to fraud:

- Example 1 – Simple Breach of Contract: You run a marketing firm in Fairfax. You sign a contract with a local business to deliver a custom advertising campaign by a deadline, and they agree to pay a fixed fee. You do your part, but the client doesn’t pay on time (or at all). They give excuses like “we’re still reviewing the materials” but never point to any actual issue with your work. This is a classic breach of contract – the client failed to perform (payment) as promised. There’s no indication they lied to induce the contract; they just aren’t honoring the deal. Your remedy is to sue for breach, seek the fee owed plus any applicable interest. You wouldn’t claim fraud because the client didn’t make any false representation – their sin was non-performance, not deception. In Fairfax General District Court, a straightforward case like this might be resolved quickly with a judgment for the amount due.

- Example 2 – Fraudulent Inducement: Now imagine you’re purchasing a small IT company in Northern Virginia. The seller provides you with financial statements showing $500,000 in annual revenue and claims verbally that “all our client contracts are locked in for next year.” You rely on this and pay a premium price. After the sale, you discover the truth: the revenue was actually $300,000 (they had falsified records) and several key client contracts weren’t renewed at all. Here, you have more than just a disappointing deal; you were duped. The seller’s false statements about revenue and contracts were material facts that induced you to buy – a textbook case of business fraud. You could sue for breach of the purchase agreement and for fraud. The breach of contract claim might cover representations and warranties that proved false, but the fraud claim covers intentional misrepresentation and may allow for punitive damages. In a case like this, Fairfax Circuit Court would likely hear it (given the amounts and complexity), and if you prove the intentional deception, a jury could award not just compensatory damages (to cover your losses in overpaying for the business) but punitive damages to punish the seller’s egregious fraud. Virginia case law (like Abi-Najm or Station #2) supports holding sellers accountable for pre-contract misrepresentations of present fact.

- Example 3 – Breach with Misrepresentation (No Independent Duty): Consider a construction scenario similar to the Dunn Construction case. You hire a contractor to build a retail space in Fairfax. The contract requires the use of steel beams of a certain grade. The contractor, trying to cut costs, uses cheaper, weaker beams but assures you (and even provides a certificate) that “Yes, we used Grade A steel as specified.” Later, an inspection or incident reveals they did not use Grade A steel. This is infuriating – the contractor lied about complying with the contract terms. You sue for breach of contract (for failing to build to specifications) and also allege fraud, as they knowingly misrepresented the construction. However, under Virginia’s source-of-duty rule, a court might treat this like Dunn: the duty to use Grade A steel was imposed by the contract, and the lie about it is essentially part of the contract breach, not a separate fraud. Unless you can frame the lie as part of a scheme that is independent (which is hard here, because the lie was specifically about a contract obligation), the fraud count may be dismissed. The contractor’s misrepresentation would be evidence of breach and perhaps grounds to claim breach was willful (potentially relevant to any claim for attorneys’ fees if the contract allows, or other contract remedies), but it likely won’t meet the independent fraud test. In Fairfax, I’d expect the contractor’s lawyer to file a demurrer to the fraud count, citing Dunn Constr. v. Cloney and Richmond Metro. v. McDevitt, and the judge would agree that you can’t get punitive damages for what is essentially a breach of contract with a cover-up. You’d proceed on the breach claim and recover the cost to fix the structure and any other losses from the delay.

- Example 4 – Concealment Leading to Fraud: You’re negotiating a partnership with another company to jointly develop a product. During talks, the partner company learns a critical fact – say, a new law was passed that will make your product much more expensive to produce – but they don’t tell you, fearing you’d back out or renegotiate. Instead, they rush you to sign the contract. Afterward, you discover this hidden landmine that severely impacts the project’s cost. If you can show the partner knew this information and had a duty to share it (perhaps because you specifically asked about regulatory issues and they kept silent or gave a half-truth), you might claim fraud by concealment. The argument is that they intentionally kept you in the dark to induce you to sign. Virginia courts have recognized that hiding a material fact can be as bad as lying, when there’s a duty to disclose. If the contract itself required full disclosure of certain matters (common in partnership agreements), failing to do so could be both a breach and evidence of fraud. In Fairfax, a case like this would hinge on proving the deliberate concealment and its materiality. If proven, you could rescind the contract (void it for fraud) and/or seek damages for the losses incurred, potentially with punitive damages given the willful deceit.

- Example 5 – Mixed Claims in Business Dispute: A scenario I handled recently (hypothetical details): A government contractor in McLean subcontracted IT work to a smaller firm. The subcontract required certain security certifications. The smaller firm provided a certificate claiming compliance, but it was forged. The work was also delivered late and defective. We sued for breach of contract (for the delays and defects) and for fraud (for the intentional misrepresentation of certification). The fraud wasn’t just failing to perform – it was a separate lie that got my client to hire them in the first place. In court, we made it clear the certification lie was an independent harm – it exposed my client to liability with the government and wasn’t simply a byproduct of the poor performance. The case settled after the judge denied the subcontractor’s demurrer on the fraud count, citing that pre-contract falsehood as actionable. This outcome shows that surviving a fraud claim can pressure a defendant to come to the table. But if we had not had solid proof of the forgery and intentional deceit, the fraud claim could have been tossed, leaving us with just the breach and far less leverage.

These examples show a spectrum: purely contractual breaches, clear-cut fraud, and the gray area in between. The Fairfax courts apply the law to sort these out – straightforward breaches are confined to contract remedies, while true fraudulent conduct is punished more severely. For business owners, the lesson is to identify early what kind of wrong you’re dealing with. Is it just that the other party didn’t live up to their word (common breach), or were you tricked from the outset or cheated in a way that violates basic business honesty? The answer will guide your legal approach.

Chapter 6: What Business Owners Should Do if They Suspect Fraud

If you’re a business owner in Fairfax County and you smell something fishy in a deal – maybe the other party’s story keeps changing, or you discover documents that contradict what you were told – you need to act promptly and prudently. Here’s my first-person advice on steps to take if you suspect fraud in a business contract situation:

1. Preserve All Evidence: Document everything. Save emails, texts, contracts, invoices – any communication or paperwork related to the deal. Fraud cases often live or die on the paper trail and digital communications. If there were false statements made, you want a record of them (for example, that flashy brochure with fake stats, or an email where the other side made assurances). Do not delete or alter anything on your side; secure it. If there are witnesses (employees, third parties) who heard representations or saw concealments, quietly take note of what they know. In Fairfax litigation, I’ve leveraged damning emails and message logs to prove a person’s intent to deceive – you’d be surprised how often people put things in writing that come back to haunt them.

**2. Don’t Take Their Word – Verify and Gather Facts: Once you suspect you’ve been lied to, start verifying claims independently. If, for example, a vendor told you they had a certain license or certification, check with the licensing authority. If a partner swore their product meets X standard, have it tested. Do this discreetly; you don’t necessarily want to tip off the other side while you’re in fact-gathering mode. Often, fraud becomes evident only after-the-fact, when things go wrong. So retrace the promises made and see what evidence you can compile that those promises were false when made. Create a timeline of events and statements. This will help any attorney evaluate the case efficiently.

3. Consult a Business Attorney Early: Time is of the essence with fraud. In Virginia, the clock for fraud claims starts ticking when the fraud “is discovered or reasonably should have been discovered” – and it’s a 2-year statute of limitations in most cases. You don’t want to miss that window because you were deliberating too long. I recommend contacting a qualified business litigation attorney as soon as fraud is on your radar. An attorney (like me) will assess whether the facts support an independent fraud claim or merely a breach. We will also help strategize on immediate steps: do we send a strong demand letter alleging fraud (which can spur settlement talks or at least freeze the other side from further misconduct)? Do we need to file a lawsuit quickly to stay within the limitation period or to seek an injunction? In Fairfax, if the matter is urgent (say the other party is dissipating assets or continuing the fraudulent behavior with others), an attorney might advise seeking a court order to prevent further harm. Early legal intervention can also help preserve evidence – for instance, we might send a litigation hold notice to the opponent instructing them not to destroy documents, knowing that Fairfax courts expect parties to safeguard relevant evidence once a dispute is apparent.

**4. Avoid Confrontational Self-Help: It’s natural to feel angry or betrayed if you suspect fraud. But be cautious in your initial response. Accusing the other party of fraud publicly or in writing without solid proof can lead to defamation claims or entrench them into denial mode. Likewise, if you’re mid-contract (e.g., they’re still supposed to deliver something), don’t immediately stop fulfilling your obligations or you risk being blamed for breaching the contract yourself. Consult your attorney on whether you should suspend performance or not. In some cases, we’ll advise continuing to act in good faith under the contract while we quietly investigate the fraud claim on the side. In others, if the fraud is blatant, we might declare the contract void due to fraud and halt performance – but you want legal guidance before taking that step.

**5. Leverage Legal Tools in Discovery: If a lawsuit is filed, Virginia law and Fairfax procedures will allow discovery – the process of obtaining evidence from the other side. This can uncover internal emails, financial records, or other data that prove the fraud. In one case, through discovery, we obtained internal memos showing the defendant company knew of a defect and had a plan to hide it from customers – a smoking gun for fraud. While you can’t start formal discovery until a lawsuit is underway, knowing it’s an option often influences whether to file suit sooner rather than later. If fraud is causing ongoing harm, sometimes filing and using subpoena power to obtain information (for example, bank records if funds were diverted) is crucial. Again, an attorney can map this out for you.

**6. Mitigate Your Damages: Courts (and juries) like to see that you acted reasonably after discovering a problem. If you realize you were defrauded, take steps to limit the harm. For example, if a supplier sold you counterfeit parts, stop using them once you know and source legit parts, even if it’s costly – those extra costs can be damages you claim. Don’t keep piling money into a venture you now suspect was based on fraud without at least a protest or notice. In fraud cases, Virginia allows recovery of losses directly caused by the fraud, but you have a duty to mitigate those losses when possible.

**7. Consider Reporting Serious Fraud: Some business fraud isn’t just civil – it can be criminal (think embezzlement, forgery, etc.). If the conduct is egregious (like an outright scam), discuss with counsel the possibility of reporting to law enforcement. Virginia has criminal statutes against obtaining money by false pretenses. While police or prosecutors might not get involved in a purely contractual setting, if someone defrauded you, criminal action could be on the table. Even short of that, if the other side is a licensed professional (say a contractor, stockbroker, etc.), you might report the fraud to their regulatory board. This can pressure a resolution, though one should tread carefully and usually only do so with legal advice – you don’t want to inadvertently defame someone by making accusations that aren’t substantiated.

**8. Protect Your Business Going Forward: Lastly, whether you pursue litigation or not, use the experience as a learning opportunity. Tighten up contract language to include representations and warranties (so that lies can also be breaches of contract explicitly). Include clauses that require disclosures of key facts and allow you to void the deal if misrepresentations are discovered. In Fairfax County’s vibrant business environment, trust but verify. Implement due diligence steps – like background checks or requiring backup documentation for claims – before sealing deals. As an attorney, I often help clients redesign their contracts and vetting processes after a fraud incident to prevent a recurrence.

In summary, if you suspect fraud, act decisively but intelligently. The path to relief is often complex – mixing contract and tort law – so getting professional guidance is critical. Fairfax County offers a strong legal framework to address fraud (with courts that will punish proven fraudulent actors), but the burden is on you as the claimant to navigate that framework effectively. By preserving evidence, seeking timely counsel, and making smart tactical decisions, you put your business in the best position to either undo the damage or obtain justice from the offending party.

Remember: As a business owner, you don’t have to figure this out alone. Fraud vs. breach can be legally intricate, but that’s what folks like me are here for. I’ve guided clients in Northern Virginia through this maze many times. The key is to be informed, prepared, and proactive. Fairfax County’s courts are ready to protect businesses from fraud, provided we present a compelling, well-founded case. And if it’s “just” a breach of contract, that’s fine too; we’ll pursue it vigorously using the tools contract law provides. Either way, knowing the difference empowers you to make sound decisions and to seek the remedies you truly deserve under Virginia law.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

-

Virginia Statutes & Court Rules:

-

Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-246 (2024). Personal actions based on contracts (statute of limitations for contracts: generally 5 years for written contracts, 3 years for unwritten).

-

Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-243 (2024). Personal action for fraud (statute of limitations: 2 years from when the fraud is discovered or should have been discovered).

-

Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-38.1 (2024). Limitation on recovery of punitive damages (caps punitive damages at $350,000 in civil actions in Virginia).

-

Va. Sup. Ct. Rule 1:4(d) (2024). Pleading requirements – allegations of fraud must be stated with particularity (Virginia’s fact-pleading rule for fraud).

Virginia Case Law:

-

Richmond Metropolitan Authority v. McDevitt Street Bovis, Inc., 256 Va. 553, 507 S.E.2d 344 (1998). – Established the source-of-duty rule: a tort claim (fraud) cannot be based on duties that exist only by virtue of a contract; misrepresentations related to a contractual duty do not give rise to fraud.

-

Dunn Construction Co. v. Cloney, 278 Va. 260, 682 S.E.2d 943 (2009). – Reaffirmed that a misrepresentation made during performance of a contract (to obtain payment due under the contract) did not create an independent fraud claim. The contractor’s false guarantee of repair was deemed part of the contract breach, barring a separate fraud action.

-

Station #2, LLC v. Lynch, 280 Va. 166, 695 S.E.2d 537 (2010). – Held that fraudulent inducement is actionable alongside breach of contract when the defendant made misrepresentations of present fact before the contract, to induce the agreement. The economic loss rule did not bar the fraud claim because an independent duty (not to commit fraud) was violated.

-

Abi-Najm v. Concord Condominium, LLC, 280 Va. 350, 699 S.E.2d 483 (2010). – Clarified that even if a contract was later signed, pre-contract misrepresentations of existing facts can support a fraud claim. The fraud is not negated just because the contract addressed the same subject matter.

-

Filak v. George, 267 Va. 612, 594 S.E.2d 610 (2004). – Emphasized that the law of torts provides redress only for violation of common law duties imposed to protect broad societal interests (like safety or honesty), not for duties that are purely contractual. In this insurance dispute, the court barred a constructive fraud claim because any duty to provide proper coverage arose solely from the contract, illustrating the source-of-duty principle.

-

Evaluation Research Corp. v. Alequin, 247 Va. 143, 439 S.E.2d 387 (1994). – Listed the elements of actual fraud in Virginia (false representation, material fact, knowledge of falsity, intent to mislead, reliance, and resulting damage), reaffirming that all elements are required for a fraud claim.

-

Flippo v. CSC Associates III, LLC, 262 Va. 48, 547 S.E.2d 216 (2001). – Noted that fraud must be proven by clear and convincing evidence, a higher standard than a normal civil case preponderance. Also reiterated that fraud cannot be based on unfulfilled promises unless there was a present intent not to perform (promissory fraud principle).

-

SuperValu, Inc. v. Johnson, 276 Va. 356, 666 S.E.2d 335 (2008). – Held that a promise of future action cannot support a claim of constructive fraud. The court reasoned that if mere unfulfilled promises (made innocently or negligently) could be constructive fraud, “every breach of contract would potentially give rise to a claim of fraud” – underscoring the need to separate tort from contract claims.

Secondary Source:

-

Shin, Anthony I. “What Is Considered Business Fraud Under Virginia Law and How Do Courts Decide These Cases?” Shin Law Office Blog (2025). – Explains in plain language the differences between business fraud and breach of contract in Virginia, with practical insights and case examples from a Northern Virginia litigator’s perspective. This article (along with related Fairfax-specific legal guides) informed several of the concepts and examples discussed above, emphasizing Virginia’s strict pleading requirements and the importance of an independent duty for fraud claims. (Note: Secondary commentary is used for explanatory context; primary law from statutes and cases governs the legal standards.)

-