Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

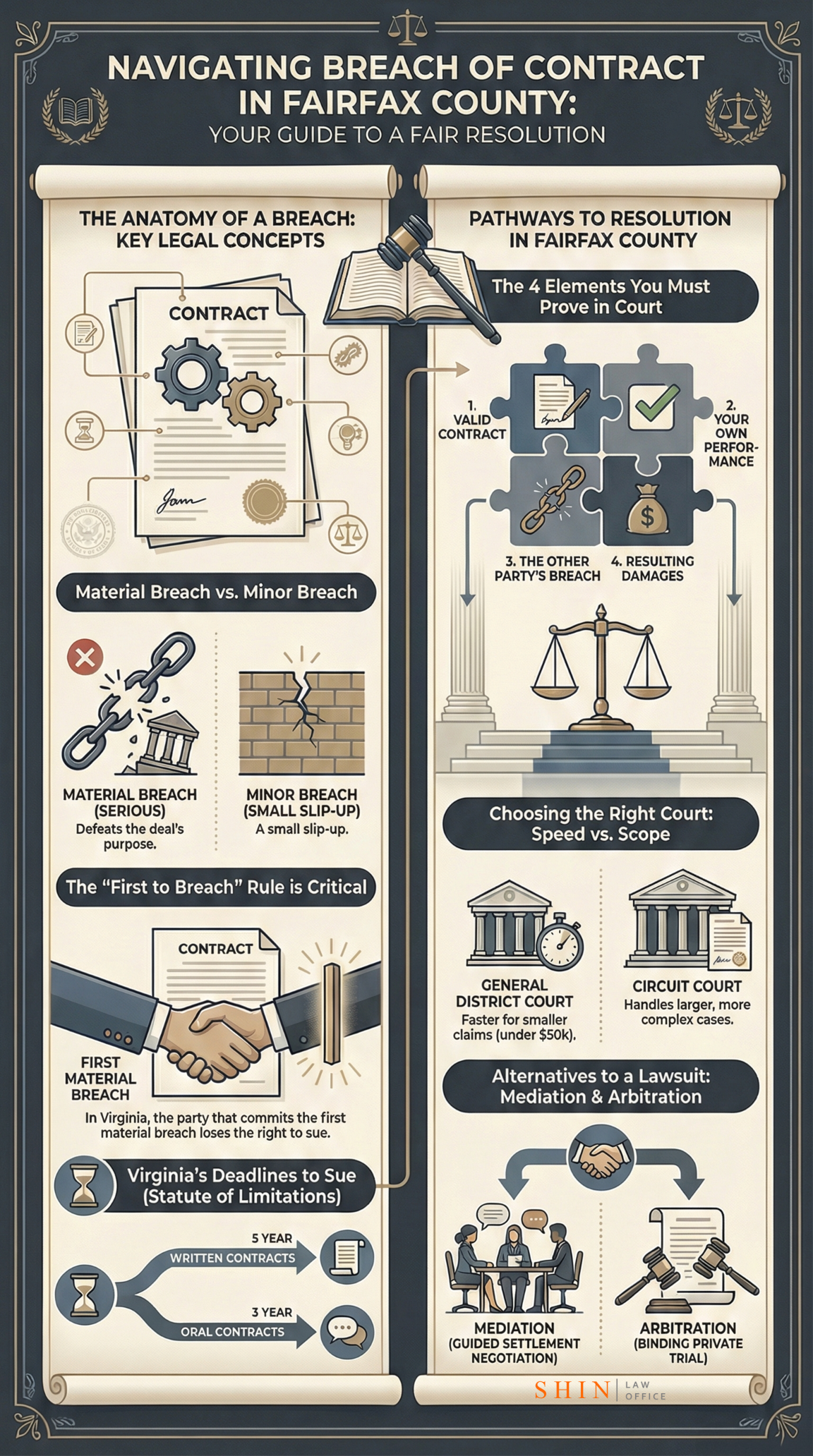

Whether you’re in Vienna, Tysons Corner, Fairfax City, Alexandria, or any bustling Northern Virginia community, broken contracts can disrupt life and business. Virginia courts strictly enforce contracts as written, meaning that if a deal goes sour, the written terms will rule – judges won’t “save” anyone from a bad bargain. Breach of contract disputes here often involve everyday scenarios such as nonpayment for services or a business deal falling apart, and they can affect individuals, small businesses, and Fortune 500 companies alike. Importantly, the first party to materially breach a contract loses the right to enforce it – so if you haven’t held up your end, you usually can’t successfully sue the other side. Resolving these disputes requires a clear understanding of Virginia’s contract law, a strategic approach (whether through the courts or alternative resolution, such as mediation), and an empathetic yet firm approach. In short, successfully navigating a contract dispute in Fairfax County means knowing your rights and remedies, acting promptly within legal deadlines, and choosing the right path (court or settlement) to protect your interests.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Understanding Breach of Contract in Fairfax County

- Chapter 2: Types of Contracts and Breaches (Written, Oral, Minor, Material, etc.)

- Chapter 3: Virginia Contract Law Basics – Elements and Enforcement

- Chapter 4: Litigation Strategies in Fairfax County Courts

- Chapter 5: Alternatives to Litigation – Mediation & Arbitration

- Chapter 6: Real-World Examples, Practical Tips, and Conclusion

- References

Chapter 1: Understanding Breach of Contract in Fairfax County

I’m a Fairfax County attorney, and I’ve seen firsthand how a breach of contract can throw someone’s world into turmoil. Let’s start with the basics: a contract is just a legally enforceable agreement – a set of promises the law will uphold. A breach of contract happens when one party fails to fulfill their end of the bargain or interferes with the other party’s performance. This sounds simple, but breaches take many forms and vary in severity, which we’ll break down in the next chapter. It’s crucial to understand that Virginia courts in our area (including Fairfax County’s) take contracts seriously and expect parties to honor the exact terms of their agreement.

From the individual who paid a contractor in Vienna for home renovations that never got finished, to the tech startup in Tysons facing a vendor who delivered faulty software, breaches of contract span all industries and personal dealings. In Fairfax County’s growing communities, everyday business runs on trust and agreements – and when that trust is broken, the legal system provides remedies to the wronged party. But pursuing those remedies can be daunting. As an attorney, I empathize with clients’ frustration: you entered a deal in good faith, and now you’re left holding the short end of the stick. In this guide, I’ll walk you through what counts as a breach, how the law applies to your situation, and the strategies we can use to address or challenge it. By understanding the lay of the land in Northern Virginia contract law, you’ll be better equipped to protect your rights and make informed decisions about your next steps.

Chapter 2: Types of Contracts and Breaches (Written, Oral, Minor, Material, etc.)

Not all contracts – or breaches – are created equal. Here in Virginia (and thus in Fairfax County), contracts can be written or oral, and breaches can range from minor slip-ups to fundamental failures. Let’s break down the key types of contracts and breaches you should know:

- Written vs. Oral Contracts: A written contract is one that’s in writing (or a digital document) and signed. An oral contract is a spoken agreement – yes, those can be legally binding! Virginia law recognizes oral contracts in many situations, though certain agreements must be in writing under the Statute of Frauds (for example, contracts for the sale of land, promises that can’t be performed within a year, or guarantees to pay someone else’s debt). The main difference in practice is proof: a written contract provides clear evidence of terms, whereas an oral contract might lead to “he said, she said” disputes over what was promised. Also, note the statute of limitations differs: you generally have five years to sue on a written contract, but only three years on an oral contract in Virginia. (For sale of goods transactions under the UCC, the limit is four years.) Waiting too long can bar your claim, so timing is critical.

- Minor vs. Material Breach: Virginia law (like most states) distinguishes between a minor breach and a material breach. A minor breach (sometimes called “non-material”) is a small deviation from the contract – something that doesn’t defeat the overall purpose of the deal. For example, if a contractor slightly delays completion of a project by a few days but it doesn’t really harm you, that might be minor. You usually cannot terminate the entire contract for a minor breach, though you may still recover any resulting damages. A material breach, on the other hand, is serious – it strikes at the heart of the agreement and substantially deprives the non-breaching party of what they signed up for. If a breach is material, the non-breaching party is typically justified in terminating the contract and suing for full damages. For instance, if you hired someone to develop a software application for your Fairfax business by a strict deadline and they never deliver anything functional, that’s a material breach – you’re freed from paying and can seek compensation for losses because the core purpose of the contract was defeated. (In Virginia, materiality often depends on factors like: Did the contract label that obligation as essential? Does the breach go to an essential part of the agreement? Does it cause significant harm such that you lose the main benefit of the deal?.) If there’s any doubt, remember the “first breach” rule: a party who commits a material breach first can’t enforce the contract against the other side, whereas a trivial breach might not destroy their rights entirely.

- Fundamental Breach: You might hear this term; it’s essentially another way to describe a breach so severe that it undermines the contract’s very foundation (i.e., a material breach). Some lawyers use “fundamental breach” to emphasize that the breach is at the core of the contract. Functionally, it allows the non-breaching party to terminate the contract and seek remedies, as if it were a material breach. In everyday usage, we usually classify this as a material breach in Virginia, but the key idea is the same: the breach gutted the deal.

- Anticipatory Breach (Repudiation): Not all breaches happen after the deadline or duty has passed – sometimes one party announces ahead of time that they aren’t going to perform their future obligations. This is called anticipatory breach or repudiation. Virginia courts will allow the other party to treat a clear and unequivocal repudiation as a present breach and sue immediately. For example, if a Fairfax supplier emails you saying, “I’m not going to deliver the equipment next month as promised,” you don’t have to wait until next month to take action – that outright refusal is an anticipatory breach. But caution: the repudiation must be clear, absolute, and unequivocal to count. If it’s ambiguous – say the supplier just expresses doubts or is rumoured to be insolvent but hasn’t flat-out refused – Virginia law will not yet consider it a breach. (In fact, the Virginia Supreme Court recently reaffirmed that, outside of sales of goods, there’s no legal right to demand “adequate assurance” of performance – meaning you can’t force a maybe-wobbly partner to confirm they’ll perform, unless they clearly repudiate. This is a bit technical, but it came up in a 2025 case involving a TV production company and the NRA – the court held that unless the General Assembly changes the law, you’re stuck waiting until a breach actually happens or is unequivocally announced.) The practical takeaway: if the other side unmistakably says “I’m out” or behaves in a way that undeniably shows they won’t perform, you can usually treat the contract as breached then and there.

Understanding these types of breaches and contracts helps set the stage. When a client in Fairfax County comes to me with a contract issue, one of my first tasks is to determine: What type of contract is it, and what kind of breach are we dealing with? This influences everything from what legal remedies are available to how we strategize the response. In the next chapter, we’ll look at the legal framework in Virginia for proving a breach and enforcing contracts – essentially, how the courts determine who is right or wrong when a breach occurs.

Chapter 3: Virginia Contract Law Basics – Elements and Enforcement

Now that we’ve defined what a breach is and its types, let’s dive into how Virginia law (and by extension Fairfax County courts) handles these disputes. In order for you (the wronged party) to win a breach of contract claim, certain elements must be proven in court. Virginia’s Supreme Court has spelled out the core elements clearly:

[Image of elements of a contract law diagram]

- Existence of a Valid Contract: First, you must show a legally enforceable agreement between the parties. This means all basic contract requirements were met – offer, acceptance, and consideration (something of value exchanged), and the contract wasn’t for an illegal purpose. For example, a written contract signed by both parties, or an oral agreement with clear terms and mutual promises, can qualify. (Remember, as discussed, some contracts need to be written to be enforceable.) I often start by asking clients for any emails, documents, or recollections that demonstrate a meeting of the minds on specific terms.

- Plaintiff’s Performance (or Excuse for Non-Performance): Although some Virginia cases bundle this into the existence of a contract or consider it implied, it’s critical to show that you did what you were supposed to do under the contract, or that you were ready, willing, and able to perform your obligations. If you haven’t performed your promises, the court won’t let you claim the other party breached. For instance, if you contracted to buy goods and you never paid the deposit that was required, you can’t sue the seller for failing to deliver. There is a big fairness principle here: a party in material breach cannot enforce the contract. Virginia’s “first material breach” rule says just that – if you committed the first material breach, you are barred from recovering for the other side’s later breach. (Minor breaches might not trigger this bar, but any significant failure on your part will.) A classic example from a Virginia case: in Horton v. Horton (1997), a wife’s refusal to sign certain documents was deemed a material first breach of a land-sale contract, which excused the husband from further performance and prevented the wife from enforcing the deal. In short, clean hands are needed – you must show you upheld your end or were excused from doing so (maybe because the other side prevented you or indicated it was pointless).

- Defendant’s Breach of an Obligation: Next, you have to prove that the other party failed to perform a contractual duty owed to you. This could be an action (they didn’t do something they promised) or sometimes a prohibited action (they did something they agreed not to do). Evidence is key: invoices, witnesses, emails, texts – anything showing the promise and the failure. For example, if a Fairfax contractor promised to build a deck but never did, we’d present the signed contract and photos or testimony showing no work was completed by the deadline. If the breach concerns poor performance rather than total non-performance, we might demonstrate that the work was defective (e.g., through expert testimony). It’s worth noting that Virginia courts interpret contracts by the “plain meaning” rule – they look at the actual words of the contract. If the language is unambiguous, the judge will enforce those words as written, without considering outside evidence of what you thought it meant. For instance, in Pocahontas Mining LLC v. CNX Gas Co. (2008), the Virginia Supreme Court reaffirmed that unambiguous contract terms are conclusive – neither party can later claim a different interpretation was intended. If your contract clearly states payments are due on the 1st of each month and the other party pays on the 20th, their good intentions won’t override the clear term; it’s a breach. On the flip side, if terms are vague or ambiguous, courts may then look at outside evidence or default rules, but they will not rewrite the contract to save someone from a bad bargain. The lesson: clear contracts upfront = clearer breach cases later.

- Damages (Injury to the Plaintiff caused by the breach): Finally, you must show that the breach caused you harm – typically a financial loss. In Virginia, the aim of contract law is to put the injured party in the position they would have been in if the contract had been performed as promised. That usually means monetary damages. Common forms of damages include: compensatory damages (direct losses and costs incurred), consequential damages (indirect but foreseeable losses caused by the breach), and, in some cases, liquidated damages (a fixed amount the contract specifies will be owed for a breach). You have to prove your damages with reasonable certainty – you can’t speculate or claim exorbitant amounts not grounded in evidence. If, for example, a Fairfax software supplier’s breach caused you to lose clients, you’d need to show documentation of those lost profits and that they were a foreseeable result of the breach. Virginia does not allow punitive damages for pure breach of contract (because a breach isn’t a crime or tort by itself), so you won’t get “punishment” money unless a separate fraud or malicious act was involved. Also, Virginia follows the American Rule on attorneys’ fees – you can’t claim your legal fees as damages for breach unless the contract explicitly provides for it or a specific law allows it. So part of my job is to evaluate the provable damages: how do we quantify what this breach cost you? Sometimes damages are nominal (a token $1) if there’s a breach but no significant loss, but usually, we’re adding up things like payments made for nothing in return, cost to find a replacement deal, lost profits, etc. We also check if the contract has a limitation of liability clause capping damages, or a clause granting attorney fees to the winner – those will shape the strategy.

If all these elements are in place, you have a solid claim. However, the other side might raise defenses. Common defenses in contract cases include arguing that no valid contract existed (e.g. claiming an agreement was never finalized, or lacked consideration or capacity), that the contract is void due to illegality or fraud, that you actually breached first (the “first breach” defense we discussed), or that the claim is barred by the statute of limitations (time ran out) or the Statute of Frauds (it was a type of agreement that needed to be written but wasn’t). They might also claim you waived the breach or accepted it (e.g. you continued to accept their performance after knowing of the issue). We have to be prepared to counter these. For instance, if they argue the contract wasn’t signed and thus isn’t enforceable, we might find part performance or other evidence that makes it binding despite the lack of a signature. If they say you took too long to sue, we’d show that you filed within 5 years or 3 years as applicable, or maybe the clock was tolled (paused) for some reason.

Enforcement in Fairfax County: Fairfax County’s courts apply these Virginia laws with fidelity. Judges here are known to be detail-oriented with contracts – they will read the fine print and expect the parties to have followed any procedures set in their agreement. For example, if your contract required a written notice of default and a 30-day cure period before termination, and you terminated immediately without notice, the court is likely to side against you because you didn’t follow the contract’s own terms. A notable Virginia case on this point is Countryside Orthopaedics, P.C. v. Peyton (2001), where a medical practice terminated a contract without giving the contractually required notice and chance to cure; the Supreme Court held that because the termination clause wasn’t followed, the termination was wrongful, even though the other party had performance issues. The lesson: honoring contractual procedures is part of enforcing contracts as written. Fairfax judges will similarly hold a party to every term – including those technical notice requirements or condition precedents – so we must be meticulous in either complying with them or explaining why they didn’t apply.

In summary, Virginia’s contract law provides a framework that is generally favorable to upholding contracts and making parties whole for breaches – but it demands that you come to court having done your homework (performed your part, documented the breach, and calculated real damages). With these legal basics in mind, we can turn to how, in practical terms, a breach of contract dispute is handled in the Fairfax County courts. What actually happens if you need to file a lawsuit, and what strategies make sense in this jurisdiction? That’s up next.

Chapter 4: Litigation Strategies in Fairfax County Courts

Outside view of the historic Fairfax County Courthouse in Fairfax, VA. If a contract dispute escalates to litigation, this is one of the venues where your case might be heard.

Litigating a breach of contract in Fairfax County means navigating the Virginia state court system, which has its own procedures and local nuances. As someone who litigates here, I’ll share what to expect and some strategic considerations. First, where do you file? In Virginia, the forum depends largely on the amount in controversy (the dollar value of the dispute) and the location of the parties or contract events:

- General District Court (GDC): The lower court in Virginia for civil claims up to a specified amount. As of now, GDC handles claims up to $50,000 in Virginia (and up to $5,000 in the Small Claims division of GDC, where you can even represent yourself). If your breach of contract case involves, say, a $20,000 dispute with a home contractor in Fairfax, you could file in Fairfax County GDC. The process there is faster and more streamlined – there’s no formal discovery (no depositions or interrogatories), and cases often get to trial within a few months. The trade-off is that you have a bench trial (no jury) and a simpler evidence presentation. GDC is often ideal for smaller matters because it’s cheaper and quicker; however, if your case is complex (lots of documents, expert testimony needed, etc.), GDC’s simplicity can be a drawback. Also, any party dissatisfied with the GDC outcome may appeal de novo to the Circuit Court (meaning a new trial as if the first trial didn’t occur) if they file within 10 days of judgment. So GDC can sometimes be a “preview” of the case. Strategically, I advise clients with strong, well-documented small cases to use GDC to save time and money – but we prepare thoroughly as if we might need to appeal to get final resolution.

- Circuit Court: The trial court of general jurisdiction for larger cases (over $50,000 in value or any case seeking injunctions or specific performance). Fairfax County Circuit Court is a busy forum – one of the largest in Virginia – with experienced judges and a well-defined procedural system. Here you can have a jury trial (in contract cases, either party can request a jury, although many contract disputes end up with a judge trial if the issues are mostly legal). Circuit Court involves formal pleadings (a detailed Complaint, a possible Motion to Dismiss or Demurrer challenging legal sufficiency, and an Answer from the defendant). Fun fact: Virginia is a “fact-pleading” state, which means your Complaint must allege the fundamental facts of your case, not just broad conclusions. The initial complaint is crucial – it needs to set out the contract, breach, and damages clearly. Fairfax courts, like others in Virginia, will dismiss claims that are too vague or legally deficient early on (they don’t let weak claims hang around). We saw this with fraud or tort claims piggybacking on contract cases – courts will demurrer (dismiss) those if they’re not specifically pled. For a contract claim, as long as you plead the elements we discussed with supporting facts (e.g. “Defendant signed a contract on X date to do Y; Plaintiff performed by doing Z; Defendant failed to pay the $ amount on date as promised; this breach caused Plaintiff to lose $X”), you should survive the initial demurrer stage.

Once in Circuit Court, expect the process to include discovery – each side can request documents from the other, send written questions (interrogatories), and take depositions (interviews under oath). In Fairfax, cases are managed by a scheduling order – the court will set deadlines for discovery, motions, and a trial date, often within roughly a year of filing (it can vary; some cases go to trial in as quickly as 6-8 months for simpler matters, others 12-18 months if complex). Fairfax judges keep the docket moving, but it’s not as lightning-fast as, say, the “Rocket Docket” federal court in Alexandria. Still, compared to some jurisdictions, you’ll find Fairfax County pushes cases along efficiently.

Local quirks and tips: Fairfax Circuit Court has a Differentiated Case Tracking Program which tailors the schedule to the case complexity. Simple disputes might get a trial date in 6 months; complex ones maybe in 1 year+. The court also requires a settlement conference or judicial settlement conference in many civil cases – effectively encouraging parties to talk settlement as the trial nears. Motions Day in Fairfax is a specific day of the week where many preliminary motions (like discovery disputes or demurrers) are heard – attorneys line up and argue their motions in a somewhat quickfire fashion. Knowing these local practices helps with strategy: for example, if the other side isn’t providing the documents we need, we file a motion to compel and schedule it on a Motions Day to keep the case on track. If there’s a flaw in the other side’s case, we might file a demurrer early to potentially knock out their claim or narrow the issues.

Evidence considerations: In a contract case, the contract document is usually Exhibit #1. Fairfax courts will require the original or a proper copy and will listen to any evidence about its authenticity if questioned. It’s smart to have any relevant emails, change orders, text messages, invoices, etc., organized – these are often the puzzle pieces that show how the breach unfolded. I often work with clients to prepare a chronology of events with supporting documents, which becomes invaluable for both settlement talks and trial. Because Virginia state courts don’t have the same liberal summary judgment practice as federal courts (it’s hard to get a case thrown out before trial unless the facts are undisputed and purely a legal question), many contract cases in Fairfax will actually reach the trial phase unless settled. At trial, if it’s a bench trial, the judge will be the fact-finder; if a jury, we will select a jury from Fairfax residents. Jury trials in contract cases are less common (juries sometimes find contract disputes a bit dry or technical), but when the facts are in dispute, a jury’s perspective can be valuable – they might be more swayed by equitable arguments or sympathy. For example, a jury might react if they feel one party clearly acted in bad faith or dealt unfairly, whereas a judge might strictly say “well, the contract allowed that harsh result”. That said, judges here are very fair and will absolutely hold a breaching party accountable – I’ve seen judges enforce contracts to the letter, but also encourage parties to find reasonable resolutions.

Court remedies: If you prevail, the typical outcome is a money judgment for damages. The court will calculate what you’re owed (principal plus possibly pre-judgment interest from the date of breach). In some cases, you might seek an equitable remedy – like specific performance (asking the court to order the breaching party to actually do what they promised, usually used in real estate contracts or unique goods) – but courts grant that sparingly and only when money can’t adequately compensate. For example, Fairfax courts might order specific performance of a contract to sell a one-of-a-kind piece of property, because no amount of money is the same as that unique property. Another equitable remedy is an injunction to prevent a breach (say, stopping a party from selling a patented item in violation of a contract). However, those are situational. Most often, it’s about damages. If you win, collecting the judgment is another step – Virginia allows you to garnish wages, seize certain assets, etc., if the debtor doesn’t pay voluntarily. It’s outside the scope of this chapter, but worth keeping in mind: a victory on paper needs to be enforced.

One more thing: Settlement and attorney fees. The vast majority of contract lawsuits settle before trial. In Fairfax, mediation is often recommended (we’ll cover that in the next chapter), and parties may negotiate directly through their lawyers. As your attorney, I monitor the mounting costs of litigation against the potential gain. Litigation can be expensive and stressful – sometimes a reasonable settlement (even if not 100% of what you’re owed) is a wiser business decision. We also examine whether the contract includes an attorney’s fee clause for the prevailing party; if so, it can encourage a wronged party to pursue their claim, knowing their fees may be covered. Conversely, if you’re being sued, a fee-shifting clause can raise the stakes – losing could mean paying the other side’s fees – so that might encourage an earlier settlement from that side. Fairfax juries and judges enforce such clauses, awarding attorney fees when appropriate (and the amounts are scrutinized for reasonableness).

In summary, litigating in Fairfax County is about being prepared and strategic: choose the right court, follow all procedural rules (the courts here have little patience for sloppy lawyering), leverage the discovery process to build your evidence, and be ready to present a compelling story that fits the legal elements. Always weigh the costs and benefits of pressing on versus settling. And remember, even as we “fight” in litigation, it’s often just a step in the larger goal of resolving the dispute favorably, which brings us to alternative approaches that might avoid full-blown court battles.

Chapter 5: Alternatives to Litigation – Mediation & Arbitration

Going to court is not the only path for resolving a contract dispute. In fact, many individuals and businesses in Northern Virginia (including Fairfax County) opt for alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods like mediation and arbitration to save time, reduce costs, or maintain privacy. As an attorney, I always consider whether an alternative route might better serve my client’s goals. Let’s explore these options and how they fit into contract issues:

- Negotiation: This is as “alternative” as it gets – simply put, talking things out. Often, a strongly worded letter from an attorney outlining the breach and demanding a remedy can jump-start serious settlement talks. Many breaches are resolved when the parties agree on a solution (partial refund, extended timeline, contract modification, etc.) without formal proceedings. I include negotiation here because it’s the informal precursor to mediation. In Fairfax County, folks are generally commercially savvy and sometimes a face-to-face meeting (with or without lawyers present) can mend a deal gone bad. I approach negotiation with empathy and firmness: I convey that I understand the other side’s perspective, but also that my client’s rights must be respected. It’s amazing how often a simple conversation can clear up miscommunication that was on the verge of becoming a lawsuit.

- Mediation: A voluntary, confidential process in which a neutral third party (the mediator) helps the disputing parties reach a mutually agreeable settlement. In mediation, nobody imposes a decision – the goal is that the parties themselves, with the mediator’s guidance, find common ground. Fairfax County has embraced mediation, especially for civil disputes. In fact, the General District Court in Fairfax offers free mediation services (often through Northern Virginia Mediation Service) for small claims and other cases. I’ve participated in court-sponsored mediation sessions at the courthouse: if both parties agree, they’ll meet in a private room with a mediator before trial to see if they can resolve the matter. If mediation fails, you still have your day in court (nothing said in mediation can be used in court – it’s confidential by statute). Mediation can also be done privately (outside of court) with a hired mediator, often a retired judge or experienced attorney. Why mediate? It’s less adversarial – you might preserve a business relationship or at least end things more amicably. It’s also faster (you can schedule a mediation next week instead of waiting months for trial) and can be significantly cheaper (one day of mediation vs. protracted litigation). In a breach-of-contract context, say a small business in Vienna is owed money by a dissatisfied client, mediation allows them to negotiate, perhaps a reduced payment in exchange for a fix, or simply to avoid court costs. Often, both sides walk away somewhat dissatisfied but relieved. As a strategy, I recommend mediation when (a) both sides have some incentive to compromise, and (b) the legal issues aren’t black-and-white clear or the cost of litigation is disproportionate to the amount in dispute. It’s worth noting that mediation success in Fairfax is fairly high when both parties are serious – I’ve seen very stubborn stand-offs finally yield once people are in the same building, confronted with the reality of trial. Even if mediation doesn’t fully resolve a case, it may narrow the issues or improve understanding, which can lead to a later settlement.

- Arbitration: Arbitration is essentially a private trial – the parties present their case to a neutral arbitrator (or a panel of arbitrators) who then renders a binding decision. Many contracts include arbitration clauses stating that any disputes will be resolved through arbitration rather than in court. For example, many construction contracts and tech service agreements in our region include arbitration provisions, often under rules of organizations such as the American Arbitration Association (AAA). Virginia law (and federal law under the Federal Arbitration Act) strongly favors the enforcement of these arbitration agreements. So if you signed a contract with an arbitration clause, the Fairfax court will likely compel arbitration if one side requests it. Pros of arbitration: It’s private (no public record like a court case), can be faster than court (though complex arbitrations can also drag on), and arbitrators with subject-matter expertise can be chosen (say you want someone well-versed in software licensing to decide a software contract dispute). The setting is more informal – often a conference room rather than a courtroom – and rules of evidence are relaxed. Arbitration decisions are final and difficult to appeal; you generally can’t appeal just because you think the arbitrator got it wrong on facts or law (appeals are only if there was some gross misconduct or exceeding of authority, which is rare). Cons: It can be costly (you often have to pay the arbitrator(s) by the hour, which in large cases can rival court costs), and some feel arbitrators may “split the baby” (compromise) more than a court might. But arbitration is common in business-to-business contracts in Northern Virginia. I have arbitrated cases where the parties appreciated the confidentiality and the ability to schedule long hearing days without the stop-and-go of a busy court docket. Strategically, if my client has a solid case and an arbitration clause applies, we don’t hesitate to arbitrate – but I prepare just as rigorously as for a trial. One thing to remember: discovery in arbitration is often more limited than in court, so we may need to rely on fewer depositions or documents, which can be a blessing or a curse depending on how much evidence we need from the other side.

- Hybrid approaches: Sometimes contracts require mediation first, then arbitration if mediation fails. It’s good to check your contract for any step clauses. Also, even during litigation, parties can agree to submit certain issues to arbitration or to retain a private judge for an expedited decision (though this is less common). Fairfax Circuit Court also offers a program of Judicial Settlement Conferences where a sitting judge (not the trial judge) will facilitate a settlement discussion as a quasi-mediator – this can be very effective, because the judge can give a frank assessment of the case’s merits, which can be a reality check for both sides.

In Fairfax County, I’ve found courts and the legal culture encourage ADR where suitable. Judges will often ask, “Have you tried mediation?” and may even pause proceedings to allow it. The key for clients is: ADR is not a sign of weakness or “giving up” – it’s often a smart business decision. You remain in control (especially in mediation) and can tailor the outcome more creatively than a court could (for example, agreeing to a payment plan, or barter, or apologies – things a court judgment won’t provide). That said, ADR is voluntary unless a contract requires it, so both parties must be on board. If the other side is completely recalcitrant or acting in bad faith, litigation might be the only way to compel a fair outcome. As your attorney, I sometimes serve in dual roles as litigator and negotiator: advancing the case while keeping the door open to settlement. It’s a balance of pressure and openness. In the end, the goal is to resolve the breach of contract in the most advantageous way for you – and sometimes that’s achieved at the negotiating table, other times in the courtroom. Next, we’ll wrap up with a look at a real-world example or two and some practical tips to keep in mind, whether you’re currently in a contract dispute or trying to prevent one.

Chapter 6: Real-World Examples, Practical Tips, and Conclusion

To bring all these concepts to life, let’s walk through a hypothetical (but realistic) scenario and then summarize some key tips.

Example Scenario: Imagine you are a small business owner in Fairfax City who hired a marketing firm from Tysons Corner to run an ad campaign. You signed a written contract for a 6-month campaign, and you paid a 50% upfront deposit of $15,000. The firm ran ads for two months, then suddenly stopped delivering new content. Your emails and calls go unanswered for weeks. Finally, the firm’s director contacts you to say they’re terminating the contract because it’s “not yielding results” and will keep the money for the time spent. You suspect they just took on a bigger client and dropped you. This is a clear breach: they agreed to provide services for 6 months and unilaterally terminated at month 2 without cause. You’ve lost the expected advertising, and now you may need to hire someone else on short notice (likely at a higher cost) to salvage the campaign.

What do we do? First, we verify the contract terms – yes, it says 6-month service period, and no early termination allowed except for cause (which, in this case, poor results isn’t listed as a cause). There’s also a clause that any termination requires 30 days’ notice and a refund of unearned fees. They gave 0 days notice and no refund – double breach. We also note an arbitration clause, for example, requiring that disputes be resolved under AAA rules. Before leaping to file a case, I’d likely send a demand letter to the firm: citing the contract, explaining their breaches, and demanding a specific remedy (e.g. “return the unused portion of the fee, say $10,000, and pay additional $5,000 for the extra cost you’ll incur hiring a new marketer, otherwise we will take legal action”). This letter shows you’re serious and often it goes up the chain to someone in the company who might overrule the hasty termination. Let’s say they either ignore the letter or deny any breach.

Under the arbitration clause, we’ll initiate arbitration rather than file a lawsuit. We file a claim with AAA, naming the contract, outlining the breach, and seeking $15,000 damages (the deposit plus other losses). Meanwhile, I’d also consider if mediation could work – perhaps propose a mediation session before the arbitration hearing. The firm might agree to mediate to avoid further costs. Suppose mediation occurs but fails because they offer only a token refund, which you find unacceptable. We proceed to arbitration. We gather evidence: the contract itself (proof of the obligation), proof of your payment, copies of emails showing you tried to get them to perform and they went silent (evidence of breach), and, if applicable, your testimony about how their sudden disappearance harmed your business (damages). The arbitration hearing day comes, and we present the case. The firm’s defense might be “results were poor, so we thought we could quit” – which holds no water legally because the contract didn’t guarantee results; it guaranteed effort for 6 months. The arbitrator, applying Virginia contract law, likely finds in your favor and awards, say, $10,000 refund plus maybe some additional costs. That award can be confirmed in Fairfax court and then enforced like a judgment if they don’t pay voluntarily.

This scenario illustrates how a breach unfolds: documentation and contract terms drive the outcome. If the marketing firm had even a half-plausible excuse (such as you materially breached by not providing the necessary information), we’d have had to fight that on the facts. But assuming your hands were clean, the law is on your side.

Practical Tips: From this example and others I’ve handled, here are some practical takeaways for anyone dealing with contracts in Fairfax County (and Virginia generally):

- Get It in Writing: Whenever possible, put your agreements in writing. It doesn’t have to be 50 pages of legalese – even a clear email chain can sometimes serve as a written contract. This avoids confusion and protects against the Statute of Frauds issues for significant deals. It’s also much easier to prove what was agreed. If you do only have an oral agreement, follow up with an email summarizing it (“Just to confirm our conversation, you’ll do X and I’ll pay Y…”). That written memo can be invaluable later.

- Read and Understand Your Contracts: This sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised how many disputes arise from one party not fully understanding the terms. Know if there’s an arbitration clause, know the termination provisions, notice requirements, etc. If something is unclear or important to you, clarify it before signing. Many litigation cases are essentially fights over ambiguous language. Clear wording upfront can save thousands in legal fees later.

- Perform Your Obligations (or Document Your Reasons Not To): If you’re the party feeling wronged but you haven’t fully lived up to your end, be careful. As we discussed, your claim might be barred by your own breach. If there’s a genuine reason you didn’t perform (like the other side prevented you, or waived the requirement), make sure that’s documented. For example, if a contractor tells you, “stop making payments, I’ll finish first,” and then later claims you breached by not paying, you need proof of that instruction. Keeping emails or written change orders is crucial.

- Act Promptly if a Breach Occurs: Don’t wait to exercise your rights. Virginia’s limitation periods (3 or 5 years) might seem long, but time flies when you’re trying to negotiate or hoping the other side fixes things. If you miss or miss deadlines, your case could be dismissed. Also, from a practical view, evidence gets stale: witnesses forget details, documents get lost. Courts (and mediators) also take into account if you acted promptly. If you complain about a breach two years after it happened, it looks less credible unless there’s a good reason. Prompt action could mean sending a legal notice or demand, or filing suit, or at least formally reserving your rights.

- Consider Business Relationships: In Fairfax’s close-knit business community, sometimes you’ll breach with someone you may encounter again. That’s why ADR can be attractive – a mediated resolution might salvage enough goodwill to work together in the future, or at least avoid publicly burning bridges. Even if not, try to separate personal emotion from business decisions. I always advise: “Think with your head, not just your heart (or gut) when deciding how far to pursue a case.” Revenge is not a strategy – recovery and resolution is.

- Mitigate Your Damages: Virginia law expects a non-breaching party to mitigate (minimize) their losses if reasonably possible. For instance, if your tenant breaches a lease and moves out, you should try to re-rent the place to mitigate rent loss (you can’t just let it sit empty for a year and charge the old tenant for all that rent without at least trying to find a replacement). In a contract case, if the other side breaches, do what you reasonably can to reduce the impact – and keep records of those efforts. It not only helps your case (courts will ask “did you try to lessen the damage?”), it also puts you in a better position morally and financially.

- Seek Legal Advice Early: Okay, as a lawyer I’m biased here, but it’s true – consulting with an attorney early on can save you from missteps. Even a one-time consultation to understand your position can be valuable. I’ve had people come to me while a contract is deteriorating; by advising them on how to document matters or which notices to send, we strengthened their eventual case or even avoided a breach altogether by renegotiating terms. In Fairfax County, there are many resources and experienced attorneys (my door is always open) and many will do an initial consult to lay out options.

Conclusion: Contract disputes are never pleasant – they often involve a sense of betrayal or unfairness because someone didn’t honor their word. In Fairfax County’s vibrant economy, I’ve seen disputes of all shapes and sizes: homeowners vs. contractors, tech companies vs. suppliers, startup partners fighting over a buyout agreement, you name it. The good news is that the law provides a path to remedies, and the courts here are well-equipped to handle these cases efficiently and fairly. My approach, as outlined above, is to combine legal rigor (understanding the rules, case law, and procedures) with strategic and empathetic counsel (understanding your unique situation, the other side’s pressures, and finding a resolution that meets your needs). Sometimes that means being a tough litigator in court, other times a creative problem-solver at the negotiation table. Often, it’s both.

I hope this comprehensive guide has demystified the process and provided a clearer picture of how breaches of contract are addressed in our area. If you’re dealing with a potential breach, you don’t have to go it alone. As we’ve discussed, there are steps you can take and help you can seek. Remember: a breached contract is not the end of the road – with the right strategy, you can often either get what you were promised or be compensated for the loss. And perhaps most importantly, you can move forward, wiser and with your interests protected.

As an attorney and a community member in Northern Virginia, my ultimate goal is to help every client facing these issues.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

- Virginia Statutes & Regulations:

- Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-246 (2024). Personal actions based on contracts (statute of limitations for contracts: 5 years for written, 3 years for unwritten).

- Va. Code Ann. § 11-2 (2024). Statute of Frauds – writing required for certain contracts (e.g., real estate, agreements not performed within a year).

- Va. Code Ann. § 38.2-209 (2025). Award of insured’s attorney fees in certain cases. (Allows recovery of reasonable attorney fees if an insurer, not acting in good faith, denies coverage or payment to an insured.)

Virginia Case Law:

- Countryside Orthopaedics, P.C. v. Peyton, 261 Va. 142, 541 S.E.2d 279 (2001). (Strict enforcement of contract terms; termination without required notice/cure was wrongful).

- Filak v. George, 267 Va. 612, 594 S.E.2d 610 (2004). (Elements of breach of contract; courts enforce agreements as written and won’t rescue a party from a bad bargain).

- Horton v. Horton, 254 Va. 111, 487 S.E.2d 200 (1997). (First material breach doctrine in Virginia: a party who commits the first material breach cannot enforce the contract).

- Pocahontas Mining LLC v. CNX Gas Co., 276 Va. 346, 666 S.E.2d 527 (2008). (Plain meaning rule: unambiguous contract terms are enforced as written, without extrinsic evidence).

- Remy Holdings Int’l, LLC v. Fisher Auto Parts, Inc., No. 5:18-cv-00039, 2022 WL 3025782 (W.D. Va. Aug. 1, 2022). (Federal case applying Virginia law; affirmed first material breach rule and that continuing to perform after other’s breach doesn’t waive the defense).

- Bennett v. Sage Payment Solutions, Inc., 282 Va. 49, 710 S.E.2d 736 (2011). (Anticipatory repudiation must be clear, absolute, unequivocal to be actionable; reiterated high threshold for anticipatory breach).

Secondary Sources:

- Virginia Code § 8.01-581.01 (Uniform Arbitration Act, 1986). (Virginia law validates and enforces arbitration agreements, in line with federal policy).

- Fairfax GDC Mediation Program – Fairfax County General District Court provides mediation services for civil cases, reflecting Virginia’s support for alternative dispute resolution.