Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

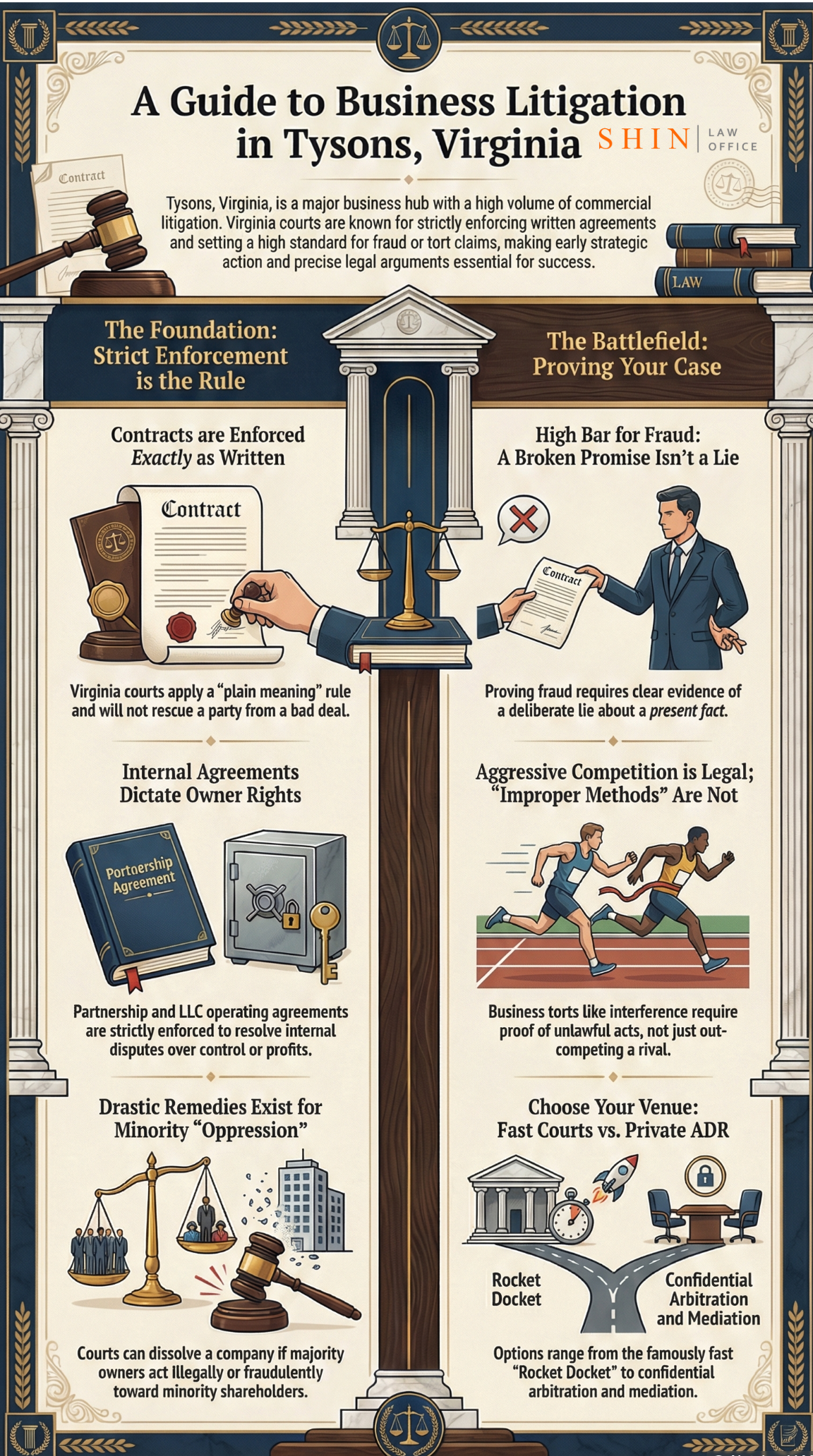

Tysons, Virginia – one of the nation’s largest business districts – is home to major corporate headquarters and a vibrant commercial sector. With this concentration of businesses comes a high volume of litigation over contracts, partnerships, and business torts. Virginia courts in this region are known for strictly enforcing contracts as written and for dismissing weak fraud or tort claims early if they lack specific factual support. Breach of contract is the most common dispute, often involving unmet payment obligations or scope disagreements. Partnership and shareholder conflicts in closely held companies are also frequent and can lead to claims of fiduciary duty breaches or even corporate dissolution. Importantly, Virginia law sets a high bar for alleging fraud; a broken promise is not fraud unless accompanied by a deliberate lie about a present fact. Business torts like tortious interference and business conspiracy require clear evidence of unlawful conduct or “improper methods,” beyond mere competition. Given Tysons’ fast-paced corporate environment, companies often seek efficient dispute resolution: the local courts (including the famously swift “Rocket Docket” in the Eastern District of Virginia) move cases quickly, and many businesses opt for arbitration or mediation to resolve issues privately and cost-effectively. In short, successful navigation of Tysons business disputes demands early strategic action, precise legal claims, and familiarity with Virginia’s corporate laws and precedents.

This article serves as a comprehensive authority resource on Virginia business litigation with a geographic focus on Tysons Corner and Fairfax County. It addresses contract enforcement standards, fiduciary duties, fraud thresholds, business tort limitations, and strategic dispute resolution options, including arbitration, mediation, and fast-paced court litigation.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Breach of Contract in Tysons Business Litigation

- Chapter 2: Partnership and Shareholder Disputes in Virginia

- Chapter 3: Commercial Fraud in Corporate Transactions

- Chapter 4: Business Torts in Virginia’s Commercial Sector

- Chapter 5: Dispute Resolution Strategies for Business Litigation

- References

Chapter 1: Breach of Contract in Tysons Business Litigation

Tysons’ businesses run on contracts – from vendor agreements to government subcontracts – and breaches of contract are the single most common catalyst for litigation in the area. Virginia law defines a breach of contract through four elements:

(1) the existence of a legally enforceable agreement,

(2) performance by the plaintiff,

(3) a failure to perform (breach) by the defendant, and

(4) resulting damages.

Courts in Virginia, including those in Fairfax County (where Tysons is located), enforce contracts exactly as written – judges will not add terms or obligations that the parties themselves did not include. This principle was underscored by the Virginia Supreme Court in Filak v. George (2004), which emphasized that courts must honor the parties’ agreement and refrain from rescuing anyone from a “bad bargain”.

Common Contract Disputes: In Tysons, most contract cases arise from ordinary business relationships that “did not play out” as expected. The most frequent trigger is nonpayment: one party delivers goods or services, and the other fails to pay as promised. For example, a Tysons IT contractor might complete a project for a client, but the client withholds payment, leading to a lawsuit. Even in seemingly straightforward nonpayment cases, Virginia courts will scrutinize the mechanics of the contract – invoicing terms, payment schedules, notice requirements – and will hold a plaintiff to any technical prerequisites for payment. A party that hasn’t followed contractual notice provisions (e.g., giving written notice of a payment dispute) might find its otherwise valid claim defeated on that technicality.

Another common dispute involves the scope of work or services. In many Tysons-area consulting and development contracts, one side will claim that certain work was included in the contract while the other side claims it was outside the scope. Virginia applies the “plain meaning” rule for contract interpretation: if the contract language is clear, courts enforce it as written and do not consider external evidence. In Pocahontas Mining LLC v. CNX Gas Co. (Va. 2008), for instance, the Supreme Court of Virginia reaffirmed that unambiguous contract terms are conclusive. Thus, if a Tysons software vendor’s contract unambiguously defines deliverables, neither party can later argue for a different interpretation. Conversely, vague terms like “industry-standard performance” can become litigation flashpoints – courts will try to interpret them objectively, but will not rewrite them to save a party from a bad deal. The lesson for businesses is to draft scope and performance terms with precision at the outset.

Termination and Default: High-stakes conflicts often erupt around contract termination. Tysons companies sometimes terminate contracts (with suppliers, service providers, even partners) as soon as problems arise, in order to cut losses. However, Virginia courts strictly enforce contractual termination clauses that require written notice and a cure period before termination; those steps must be followed to effect a valid termination. In Countryside Orthopaedics, P.C. v. Peyton (Va. 2001), the Supreme Court made clear that a party who ended a contract without giving the contractually required notice and opportunity to cure was in the wrong, even though the other party had performance issues. Thus, a Tysons business that “fires” a vendor or partner on the spot, without adhering to the contract’s termination procedure, risks being found in breach itself. Courts in this region often see cases where one party terminated first and tried to justify it later – a “dangerous approach under Virginia law”.

Contract Litigation Environment in Northern Virginia: Because Tysons is a major corporate hub, the ripple effects of contract disputes can be severe – affecting government compliance, investor confidence, and operations. This urgency means parties here tend to escalate serious contract disagreements quickly, rather than tolerate prolonged uncertainty. The local courts are accustomed to fast-paced business litigation and expect parties to be well prepared, with clear contracts and evidence from the outset. Notably, Virginia’s statute of limitations for contract claims is five years for written contracts (and three years for oral contracts). For contracts governed by the Uniform Commercial Code (e.g. sale of goods), a four-year limitations period applies. Tysons companies should keep these deadlines in mind – waiting too long to sue on a broken contract can forever bar the claim (Virginia’s courts strictly enforce these filing deadlines).

Influence of Federal Contracts: A significant number of Tysons businesses are government contractors or work on interstate deals. These contracts often include arbitration clauses or are subject to federal law. For instance, many larger contracts invoke the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) for dispute resolution across state lines. As a result, even Virginia courts will enforce arbitration agreements under the FAA in appropriate cases. Moreover, disputes involving federal projects may be subject to the Federal Contract Disputes Act for claims against the government. In practice, a Tysons defense contractor with a dispute over a subcontract might end up in arbitration or before the Federal Board of Contract Appeals rather than the Fairfax Circuit Court. Awareness of these possibilities is key in formulating a strategy.

Key Takeaway: In Tysons and Northern Virginia, breach-of-contract cases hinge on the terms of the written contract and the parties’ adherence to them. Courts will enforce clear terms strictly – whether on payment, scope, or termination – and will not save a party from a poorly drafted agreement. Businesses should invest in careful contract drafting and document their performance and communications. Many costly lawsuits could be avoided or won by “disciplined performance documentation” and vigilance in following contract procedures. When in doubt, seeking legal advice early – before a contractual relationship deteriorates – can prevent a breach from escalating into full-blown litigation.

Chapter 2: Partnership and Shareholder Disputes in Virginia

Not all business fights pit company against company; many begin inside the business. Tysons hosts numerous closely held companies, startups, and professional firms where co-owners’ relationships can sour. Partnership disputes (and similar conflicts among LLC members or corporate shareholders) are among the most personal and challenging business cases. When trust breaks down between business partners in a Tysons venture – be it a two-partner tech startup or a family-owned government contracting firm – the fallout often leads to litigation. Common flashpoints include disagreements over control and decision-making, claims that one owner is being excluded or treated unfairly, fights over distribution of profits, or accusations that someone is diverting business opportunities for personal gain. Virginia courts approach these cases with structured analysis, focusing on legal rights and duties rather than emotions.

Fiduciary Duties of Partners and Corporate Officers: Under Virginia law, those in control of a business may owe fiduciary duties to each other or to the company. A fiduciary duty is a special obligation to act in another’s best interest, arising from a relationship of trust. In a traditional partnership, the Virginia Uniform Partnership Act provides that each partner owes duties of loyalty and good faith to the others. Specifically, Code of Virginia § 50-73.102 mandates that partners must account for any benefits and avoid dealing with the partnership adversely, essentially requiring honesty, fair dealing, and adherence to the law in partnership affairs. Partners cannot contract away certain core duties – for example, they cannot eliminate the right of a co-partner to access the partnership’s books or expect fair dealing. Likewise, corporate directors and officers in Virginia have fiduciary duties of loyalty and care towards the corporation and, indirectly, its shareholders. They must act in good faith and in the company’s best interests, avoiding self-dealing and conflicts of interest. Managing members of an LLC similarly owe duties to the company (and possibly to fellow members, depending on the operating agreement).

Importantly, Virginia law allows a business’s governing documents – such as partnership agreements, corporate bylaws, or LLC operating agreements – to define or even limit fiduciary duties to some extent. The Virginia Supreme Court in Flippo v. CSC Associates III, L.L.C. (2001) acknowledged that an LLC operating agreement can modify fiduciary obligations, and courts will enforce those terms as written. In practice, this means a well-drafted shareholders’ agreement or LLC operating agreement in a Tysons company might waive certain duties or outline specific procedures that partners must follow. For instance, the agreement could permit a partner to engage in outside businesses, which would otherwise be a breach of loyalty. Courts will generally uphold such provisions, as long as they don’t completely eliminate the essential fiduciary core (e.g., one cannot contract to allow outright fraud).

However, not every business relationship carries fiduciary duties. Ordinary commercial dealings do not automatically create fiduciaries. Simply co-owning a business or working closely together isn’t enough; there must be a special trust and reliance. Virginia courts “do not lightly impose fiduciary duties between sophisticated business actors”. For example, just because two companies in Tysons form a joint venture on a project does not mean they owe each other fiduciary loyalty – their duties might remain purely contractual. The law looks for one party to have power over the other’s interests, or a relationship akin to that of trustee and beneficiary, before imposing fiduciary duties. This principle was illustrated in Augusta Mutual Insurance Co. v. Mason (Va. 2007), where an insurance company sued its agent: the court held no independent fiduciary duty was breached because any duty “existed solely because of the contractual relationship” – in other words, it was a contract matter, not a special trust scenario.

Minority Shareholder “Oppression” and Remedies: A recurring theme in internal disputes is the complaint by minority owners that the majority is running the business unfairly – e.g., withholding dividends, paying excessive salaries to insiders, excluding the minority from decision-making, or squeezing them out. While many states have explicit “oppression” statutes, Virginia addresses these situations through a judicial dissolution remedy. Under Code of Virginia § 13.1-747, a minority shareholder in a Virginia corporation can petition a court to dissolve the company if those in control have acted in a manner that is illegal, oppressive, or fraudulent toward the minority. Dissolution is a drastic remedy (essentially the “corporate death penalty”), but Virginia courts have not hesitated to use it when warranted. For example, in Colgate v. Disthene Group, Inc. (Cir. Ct. 2012), minority shareholders of a Virginia company proved that the majority engaged in a pattern of self-dealing and unfair conduct (cutting dividends, misusing corporate assets, etc.), and the court ordered the corporation dissolved to protect the minority’s rights. In another case, May v. R.A. Yancy Lumber Corp. (Va. 2019), the court blocked majority shareholders from circumventing a supermajority voting requirement for a major asset sale, emphasizing that statutory protections (like requiring a two-thirds vote for a sale, per Code § 13.1-724) cannot be sidestepped by bylaw maneuvers. These cases show that Virginia courts will intervene when the majority conduct “departs from standards of fair dealing” and violates the reasonable expectations of minority investors.

That said, minority owners should understand that Virginia law does not guarantee them a veto or a share of control absent an agreement. Courts will not second-guess legitimate business decisions by the majority simply because they disappoint the minority. As one practitioner puts it, “Virginia law does not automatically protect minority owners from business decisions they disagree with”. Judges look for actual breaches of legal duty – like a provable breach of fiduciary duty, a violation of the bylaws or statutes, or fraud – rather than general unfairness. In Simmons v. Miller (Va. 2001), for example, the Supreme Court held that claims by minority shareholders for diversion of company assets had to be brought as a derivative suit on behalf of the corporation, not as personal claims, because the injury was to the company. This “derivative vs. direct” distinction means that if the harm affects all shareholders (or the whole company), an individual cannot sue solely for personal relief. The practical result is that many intra-company disputes in Tysons end up framed either as derivative actions or as dissolution petitions, rather than personal damage claims by minority holders.

Litigating Internal Disputes: When partnership or shareholder disputes reach court in Virginia, the first thing judges examine is the governing documents – the partnership agreement, operating agreement, or corporate bylaws. These documents are essentially treated as contracts among the owners, and courts enforce them strictly. For instance, if an LLC’s operating agreement in Tysons specifies how members can be removed or how profits are allocated, the court will enforce those terms. Many internal fights fizzle out or are resolved once the clear language of an agreement is pointed out. It’s situations not covered or worsened by ambiguous terms that tend to lead to protracted litigation. Common allegations in lawsuits include: majority owners diverting opportunities or funds for themselves, denying a minority their rightful say or share, violating non-compete clauses, or deadlocking the company to the detriment of the business. If fiduciary duties apply (as they often do in closely held businesses), claims of breach of fiduciary duty are frequently added – e.g., accusing an officer of self-dealing or a partner of secretly starting a competing venture. Virginia courts do carefully evaluate these claims: they won’t infer wrongdoing just because one side feels mistreated; concrete evidence is required that the accused party exceeded their authority or violated a clear duty. As noted earlier, courts are wary of turning every business quarrel into a fiduciary case – they demand a showing of actual abuse of trust or violation of established obligations, not merely “hurt feelings or expectations”.

Resolutions and Example Outcomes: Many partnership disputes in Tysons are resolved through negotiated buyouts or settlements rather than full trials. Virginia law encourages alternative dispute resolution: a disgruntled partner might mediate a fair buyout at a fair price, or the company may restructure to separate warring factions. Indeed, lawyers often attempt mediation first, given that preserving some value (and relationships) is better than destroying the business through litigation. When a resolution can’t be reached, Virginia courts have broad powers to craft remedies: they can order an accounting of finances, appoint a custodian or receiver to manage the business temporarily, or in extreme cases, decree dissolution and supervise the winding up of the business (as in the Colgate case). In an LLC context, courts might allow a dissociated member to receive fair value for their interest if the operating agreement or Code § 13.1-1047 (LLC judicial dissolution) applies. The key for practitioners is to use these tools strategically. For example, the mere threat of a dissolution petition can bring a recalcitrant majority to the bargaining table, since dissolution could harm everyone.

Key Takeaway: Partnership, LLC, and shareholder disputes in Tysons demand both legal and interpersonal finesse. From a legal standpoint, know your rights and duties: consult the company’s governing documents and Virginia statutes (such as the Partnership Act or the Code of Virginia) to understand what each party can and cannot do. A partner who withholds information or usurps a business opportunity is likely breaching fiduciary duty, while a majority owner who freezes out a minority might trigger statutory remedies. From a practical standpoint, act early – small resentments can rapidly escalate to lawsuits when business fortunes decline. Document everything: internal communications, financial records, and official decisions should be maintained, as these often become evidence if allegations fly. Lastly, consider mediation or a negotiated separation; preserving the business’s value and the parties’ sanity can often be achieved through a buy-out or split, avoiding the high cost and uncertainty of court. Virginia judges, especially in Fairfax, appreciate when business owners make good-faith efforts to resolve their disputes – but if called upon, the courts will impose discipline and, when justified, hold wrongdoers accountable under the law.

Chapter 3: Commercial Fraud in Corporate Transactions

Allegations of fraud often surface in business litigation, but in Virginia, they face a much higher bar than breach of contract claims. It’s common for a disappointed businessperson to feel defrauded when a deal goes south – “They lied to me!” – but Virginia law maintains a clear line between a broken promise (contract breach) and actual fraud. In Tysons, where many high-stakes deals occur, understanding this distinction is critical. Courts in this jurisdiction are quick to dismiss fraud claims that are essentially dressed-up contract disputes or lack specific evidence of deceit. As one Northern Virginia litigator observes, “fraud is not a catchall for bad behavior or broken commitments” – it requires a deliberate lie about a present fact, proven by clear and convincing evidence.

What Constitutes Fraud: Under Virginia law, actual fraud consists of six elements that the plaintiff must prove by clear and convincing evidence (a higher burden than the usual preponderance of evidence in civil cases). These elements are:

- False Representation: The defendant made a false representation – a statement or act that was untrue.

- Material Fact: The misrepresentation was about a present, material fact (something concrete and current, not just opinion or future intent).

- Knowledge: The defendant knew the representation was false (or made it recklessly, not caring whether it was true).

- Intent to Mislead: The representation was made with the intent to mislead or deceive the plaintiff.

- Reliance: The plaintiff relied on that false representation, and such reliance was reasonable under the circumstances.

- Damage: The plaintiff suffered damage as a direct result of the reliance.

All six elements must be present for a fraud claim to succeed. If any element is missing – for instance, if the plaintiff cannot show they reasonably relied, or there were no damages – the fraud claim fails. This strict approach means that many times, what a businessperson perceives as “fraud” is not legally fraud. For example, if a Tysons vendor promises to deliver software by December but delivers in February, that delay might be a breach of contract, but it isn’t fraud unless the vendor lied at the outset about their ability or intention to meet the deadline.

Present Fact vs. Future Promise – The Station #2 Rule: Virginia draws a crucial distinction: a misrepresentation of present fact can be fraud, but an unfulfilled promise or statement about future events is typically not. The Supreme Court of Virginia made this clear in Station #2, LLC v. Lynch (2010). In that case, a landlord’s promise to do certain renovations was broken, and the tenant sued for fraud. The Court held that failing to carry out a promise is not fraud unless there was an intention not to perform at the time the promise was made. In legal terms, a promise made with a present intention not to fulfill it (sometimes called promissory fraud) can qualify as fraud, but simply failing to perform is not enough. Thus, to turn a contract claim into a fraud claim, a Tysons plaintiff must uncover evidence like internal emails or statements indicating the other side never intended to do what they promised. Absent such evidence, courts will treat it as a contract matter only. This principle was reinforced again in Abi-Najm v. Concord Condominium, LLC (Va. 2010), where condo buyers alleged the developer’s sales promises were false – the court emphasized that fraudulent intent must exist at the time of the representation; optimistic projections or plans that later don’t pan out are not fraud.

Constructive Fraud and Negligent Misrepresentation: Virginia also recognizes constructive fraud, a false representation made innocently or negligently that deceives someone. The difference is that for constructive fraud, the defendant may not have evil intent; however, all other elements, including misrepresentation of a fact and reasonable reliance, still apply. Courts are equally stringent with constructive fraud claims. In Mortarino v. Consultant Engineering Services, Inc. (1996), the Virginia Supreme Court rejected a fraud claim that lacked specific factual support, signaling that broad allegations or misunderstandings don’t amount to fraud. More pointedly, Abi-Najm (2010) also clarified that statements that are merely “hopeful predictions or contractual expectations” cannot form the basis of even constructive fraud. In practice, that means if a Tysons CEO innocently overstates next year’s expected sales in negotiations, and the deal later disappoints, the other side likely cannot claim fraud – puffery or optimistic projections are generally not actionable.

Remedies and Risks in Fraud Cases: Successfully proving fraud in a business transaction carries potent advantages for the plaintiff. Unlike a simple contract breach, fraud can open the door to punitive damages (to punish the wrongdoer) and tarnish the defendant’s reputation. Virginia law caps punitive damages at $350,000 by statute, but even the threat of them adds pressure to the case. Moreover, a fraud finding implies moral wrongdoing – something businesses usually want to avoid at trial for reputational reasons. In Tysons, where companies value their standing in the business community, an adjudicated finding of fraud can be very damaging. It’s worth noting too that certain fraudulent acts can lead to criminal liability. Virginia’s criminal code makes it a felony to obtain money or property by false pretenses (Code of Virginia § 18.2-178), to issue bad checks (§ 18.2-181), or to embezzle funds (§ 18.2-111). In a scenario where, say, a Tysons investment adviser lies to a client about how funds will be used, they might be sued civilly for fraud and also prosecuted for securities fraud or embezzlement. While civil and criminal cases are separate, the possibility of criminal charges often looms in the background of serious fraud disputes (and can heavily influence settlement discussions).

Examples: To illustrate, consider a Tysons-based tech firm that is negotiating a joint venture. If one side secretly knows its technology cannot meet the specifications but promises otherwise to clinch the deal, and later evidence (like internal memos) shows they knew of the shortfall, this could constitute fraud – a knowing lie about a present fact (the tech’s capability). The deceived partner could sue for rescission of the contract and damages, possibly even punitive damages for the willful deception. Conversely, if that tech simply underperforms due to unforeseen issues, it’s likely only a contract issue. Another example: A seller of a business in Tysons provides the buyer with falsified financial statements. The buyer relies on them and overpays. This is classic fraud – misrepresentation of current fact (the financials) with intent to induce reliance. The buyer could seek damages for the difference in value and possibly punitive damages, and the seller might even face criminal investigation for fraud.

Limitations and Strategy: Virginia imposes a relatively short statute of limitations on fraud – generally 2 years from when the fraud is discovered or should have been discovered (with an absolute cutoff of 1 year from discovery in certain cases). A business that suspects it was defrauded must act promptly. In practice, in Tysons, many fraud disputes are accompanied by breach-of-contract claims. Plaintiffs often plead both to cover their bases. However, judges often require the fraud claim to stand on its own legs (independent of the contract) – this is related to Virginia’s “source of duty” rule, which prevents turning contract duties into tort claims. In other words, if the only wrong is not doing what the contract says, you can’t sue in tort (fraud) unless there was an independent duty (like the duty not to lie outside the contract). For instance, if a contract says nothing about a certain risk and one party conceals it, that might violate a common law duty to disclose material facts in some contexts (like fiduciary relationships), but in an arm’s-length deal, caveat emptor (buyer beware) often applies.

For legal practitioners and stakeholders, the takeaway is twofold: (1) Don’t automatically allege fraud in every broken deal – in Virginia, you need a smoking gun of deceit to survive in court. And (2) if you are alleging fraud, plead it with particularity and marshal evidence early. Courts in this area will likely dismiss vague fraud claims at the pleading stage or on summary judgment if they lack concrete facts. On the flip side, if you’re defending a Tysons business accused of fraud, one effective strategy is to argue that the complaint really sounds in contract and lacks the specific misrepresentation needed for fraud. Often, defense counsel will file a demurrer (motion to dismiss), pointing out that the plaintiff has not identified any specific false representation of a present fact. Given Virginia’s case law (e.g., Station #2, Abi-Najm, Mortarino), courts frequently agree and narrow the case by dropping the fraud count.

Key Takeaway: Honesty is paramount, but not every broken promise is a lie. Tysons companies should ensure their marketing and negotiation statements are accurate and not overhyped to avoid later claims of misrepresentation. At the same time, they should perform due diligence – trust but verify – when entering deals, because if something seems too good to be true, Virginia law expects the buyer to be somewhat cautious. When fraud does occur – true, deliberate cheating – Virginia courts will provide a remedy, and even potentially punitive damages, to the wronged party. But absent clear evidence of deceit, a dispute will likely be confined to contract law. This rigorous approach ultimately protects businesses in Tysons by discouraging frivolous fraud allegations and focusing on real, provable dishonesty.

Chapter 4: Business Torts in Virginia’s Commercial Sector

Beyond contracts and fraud, business torts make up the bulk of common business litigation in Tysons. “Business torts” refer to wrongful acts, outside of breach of contract, that cause economic harm to a business or its interests. Virginia law recognizes several such torts – including tortious interference with contracts or business expectancies, business conspiracy, misappropriation of trade secrets, breaches of fiduciary duty (in certain contexts), and commercial defamation, among others. These claims often arise when competitive pressures or internal strife lead someone to cross legal lines (e.g., poaching a competitor’s clients using improper means, or two ex-employees colluding to harm their old company). However, Virginia courts approach business torts with caution, frequently weeding out claims that are speculative or that effectively duplicate contract matters. In Northern Virginia especially, judges are alert to plaintiffs potentially wielding tort claims as weapons to gain leverage in what is essentially a business competition issue.

Tortious Interference with Contract: One of the most commonly alleged business torts in Tysons is tortious interference, often in the context of employee departures or competitive business moves. Tortious interference occurs when a third party intentionally disrupts an existing contractual relationship causing one party to breach the contract. For example, if Company A in Tysons has a contract with a client, and Company B intentionally induces that client to break the contract and switch to Company B, A might sue B for tortious interference. Under Virginia law, as set forth in Chaves v. Johnson (1985), the elements of tortious interference with contract are:

- A valid, enforceable contract exists between the plaintiff and a third party.

- The defendant knew about this contract.

- The defendant intentionally caused one party to breach or terminate the contract.

- The defendant employed improper methods in causing the interference.

- Resulting damage to the plaintiff.

Notably, it’s not enough that the third party knew of the contract and acted intentionally; improper methods are the crux. Virginia strongly protects and encourages fair competition. So, a competitor can lawfully woo customers or hire at-will employees, as long as they do so lawfully. As the Supreme Court explained in Duggin v. Adams (1987), “competition, even aggressive competition, is not improper.” Improper methods include illegal or independently tortious acts or unethical conduct that violates established standards of trade or profession. Classic examples of improper methods are: inducing breach through fraud or misrepresentation, using confidential information or trade secrets obtained unlawfully, threatening litigation or other unlawful acts, or violating a restrictive covenant. Simply offering a better deal or a higher salary to someone under contract is not tortious interference in Virginia.

In practice, many tortious interference claims in Tysons follow a pattern: a key employee leaves Company A for Company B, and a bunch of clients follow. Company A alleges interference, claiming Company B (and the employee) solicited those clients in violation of non-solicitation agreements or misused A’s client lists (which might be trade secrets). Virginia courts will dissect such cases to see if the “improper method” element is truly met. If the employee simply announced their new job and clients chose to move, that’s competition. But if the employee took a confidential client database or started soliciting clients before leaving (breaching a fiduciary duty or contract), that could be improper. In Lewis-Gale Medical Center, LLC v. Alldredge (2011), for instance, the Supreme Court emphasized the need to balance lawful competition with the policing of improper conduct, indicating that normal competitive behavior (even if it causes a contract to end) is not actionable without an illicit element.

Tortious Interference with Business Expectancy: A related but distinct tort involves interference with business expectancy – essentially a probable future economic relationship (like a near-certain sales deal or the likelihood of contract renewal) rather than an existing contract. These claims face an even higher hurdle because Virginia law is skeptical of protecting “expectancies,” which by nature are uncertain. The plaintiff must show a reasonable probability of a business opportunity (not just a hope or a speculative chance) and, again, that the defendant intentionally interfered through improper methods. In Commercial Business Systems, Inc. v. Halifax Corp. (1997), the court underscored that a plaintiff must demonstrate a probability of future economic benefit, not a mere possibility, to have a cognizable expectancy. For example, if a Tysons firm was on the verge of winning a contract renewal and a competitor sabotaged its chances by spreading false rumors, that could be interference with business expectancy – but if the chances of winning were speculative, the claim fails. The elements mirror those for contract interference, including requiring an improper method and resulting damage. The bottom line is that Virginia courts tightly cabin these torts to avoid stifling healthy market competition: merely out-competing someone for a piece of business is not unlawful unless done with egregious tactics (like defamation, bribery, or theft of trade secrets).

Statutory Business Conspiracy: Virginia has a unique and powerful business tort in its business conspiracy statute, Code §§ 18.2-499 and 18.2-500. Although codified in the criminal code (18.2 means Title 18.2 Crimes), it provides a civil cause of action for treble damages and attorney’s fees when two or more persons combine to willfully and maliciously injure another in their business. This civil conspiracy claim (sometimes called the business conspiracy or statutory conspiracy) is frequently tacked onto complaints in Tysons business disputes because of the allure of treble damages. However, courts treat it “with extreme caution”. To prevail, a plaintiff must prove four elements:

- A combination or agreement between two or more separate persons;

- Legal malice – meaning the defendants acted intentionally, purposefully, and without lawful justification (not necessarily ill-will, but a conscious unlawful purpose to harm);

- An underlying unlawful act or tort that the conspirators committed (conspiracy is not independent – there must be a wrongful act like fraud, theft, etc., done in concert);

- Resulting business damage to the plaintiff.

Critically, the Virginia Supreme Court in Almy v. Grisham (2007) affirmed that a conspiracy claim cannot stand without an actionable underlying tort or illegal act – the agreement to harm alone isn’t enough. This often leads to conspiracy counts being dismissed if the primary tort (say, fraud or interference) is dismissed or not proven. Another common hurdle is the “intracorporate immunity” doctrine: a corporation cannot conspire with itself through its own employees acting within the scope of their employment. In Fox v. Deese (1987), the Court held that employees of the same entity, acting in their official capacities, constitute a single entity and are incapable of conspiring with each other. For Tysons companies, this means you generally can’t sue a group of your own officers or a parent and subsidiary for conspiracy, since they’re legally one “person” in this context. You need at least two distinct actors. For example, two rival companies colluding to drive a third out of business could be a conspiracy, but a CEO and CFO of the same company scheming to harm a minority shareholder likely cannot (instead, that’s addressed as a breach of fiduciary duty or oppression issue).

Virginia courts, particularly in Fairfax, often scrutinize conspiracy claims early because of their potency (triple damages) and potential for abuse. Judges expect detailed allegations – who agreed with whom, when and where, and what exact unlawful act was committed. General claims that “the defendants conspired to harm our business” without specifics won’t survive. In practice, if a Tysons business alleges that two competitors conspired to poach its employees and clients, it must pinpoint specific meetings or communications and unlawful acts (like theft of trade secrets or defamation) that furthered the scheme. Without that, the claim likely will be dismissed. Simmons v. Miller (2001) further explained the malice element: the plaintiff must show the conspirators acted with “legal malice,” meaning intentionally and without any legal justification or excuse, with the aim of causing harm. Normal competitive behavior – such as undercutting a competitor’s price or enforcing one’s contract rights – is not malicious or conspiratorial if done with lawful justification. Thus, many conspiracy claims fail because what the plaintiff sees as a “plot” is often just business as usual (albeit aggressive business). Overall, while the business conspiracy statute is a powerful tool (and Tysons litigators do deploy it, given the high stakes in some corporate feuds), it is a double-edged sword: using it without strong factual basis can backfire, undermining the case’s credibility.

Misappropriation of Trade Secrets: In Tysons’ technology and government contracting sectors, another common business tort issue is the theft or misuse of confidential business information. Virginia has adopted the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (VTSA), Code of Virginia §§ 59.1-336 to 59.1-343, which provides a civil cause of action for misappropriation of trade secrets. A “trade secret” is broadly defined as business or technical information (formula, program, method, customer list, etc.) that has independent economic value from not being generally known and that the owner reasonably protects. If, for example, a former employee of a Tysons software company downloads the company’s client database or proprietary code and brings it to a competitor, the company can sue under the VTSA. The Act allows for injunctive relief, damages for actual losses and unjust enrichment, and even punitive damages and attorneys’ fees if the misappropriation was willful and malicious. Trade secret litigation in Virginia often arises alongside breach-of-contract (non-disclosure or non-compete) and fiduciary-duty claims. Virginia courts will issue injunctions to prevent use of stolen trade secrets – a critical remedy if, say, a Tysons firm’s competitive edge (like a unique design or process) is at risk of being disclosed or used by a rival. One advantage of the VTSA is it displaces some common law claims; for instance, one cannot generally bring a common law claim for “conversion of confidential information” – you must proceed under the VTSA if it’s truly a trade secret matter. This is to provide a uniform and exclusive remedy in this area.

Breach of Fiduciary Duty as a Tort: As discussed in Chapter 2, breaches of fiduciary duty by corporate officers, directors, or partners can be framed as tortious conduct. Virginia law historically was somewhat unclear on whether “breach of fiduciary duty” is a standalone tort (some older cases suggested that if the duty arises solely from contract, it might not be a separate tort). However, when a true fiduciary relationship exists (such as an officer to a corporation), Virginia courts treat a breach of loyalty or care as a tort, with remedies including damages or equitable relief. For example, in Today Homes, Inc. v. Williams (2006), two corporate officers secretly took a corporate opportunity (a land development deal) for themselves; the court found they breached their fiduciary duty by diverting it and held them liable for the corporation’s lost profits. In Tysons, if a high-level executive starts a competing business on the side and siphons clients (without the company’s consent), that is a breach of fiduciary duty and the company can sue for damages (and likely get an injunction). The key is showing the person was a fiduciary and abused their position of trust for personal gain. Virginia also recognizes certain specific applications, like the “corporate opportunity doctrine”, which forbids officers from usurping an opportunity that rightfully belongs to the corporation.

Other Business Torts: Other torts occasionally arise, for instance, commercial defamation or business disparagement (when false statements harm a business’s reputation or earnings). A notable point in Virginia is that the statute of limitations for defamation is 1 year, which is shorter than for many other business claims, so defamation suits must be filed promptly. If a Tysons company is the victim of a competitor’s smear campaign (e.g., spreading false rumors that its product fails safety tests), it could sue for defamation and, potentially, under the business conspiracy statute if two or more actors coordinated the disparagement. Virginia also has an old cause of action for “insulting words” (Code § 8.01-45), though that’s rarely used in business contexts.

Key Takeaway: Business torts provide remedies for unfair and unlawful competition and internal misconduct, but Virginia courts require specific, provable misconduct – not just aggressive business moves – to be present. Tysons businesses dealing with competitor pressures should understand that vigorous competition is lawful and even encouraged: you can lawfully hire your competitor’s at-will employees, solicit their customers (if no contract prohibits it), and innovate to outdo them. It crosses into tort territory only if you cheat or attack the competition through illicit means – for example, by stealing trade secrets, lying about a competitor’s products, poaching employees in breach of non-compete agreements, or conspiring to corner a market through illegal tactics. Internally, officers and partners must remember their legal duties – self-enrichment at the company’s expense or secret deals will trigger liability. For legal practitioners in Tysons, the success of a business tort claim will hinge on gathering evidence of these improper methods: emails showing a conspiracy, forensic proof of data theft, testimony about false statements made to customers, etc. Conversely, defending against such claims often involves demonstrating the legitimacy of the defendant’s conduct (e.g., “Yes, we hired their salesperson, but we never told him to bring any confidential files or break any contract – we competed fairly”). Given Northern Virginia judges’ tendency to cut off overreaching claims early, a well-founded factual narrative is essential to either side. Ultimately, Virginia’s balanced approach to business torts aims to deter malicious business behavior without undermining the competitive drive that makes Tysons an economic powerhouse.

Chapter 5: Dispute Resolution Strategies for Business Litigation

Dispute resolution in Tysons’ business context often requires a strategic blend of litigation savvy and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) techniques. Because of the high stakes and fast pace of commerce in Northern Virginia, both business stakeholders and their attorneys place a premium on resolving disputes efficiently and favorably, while minimizing disruption. This chapter explores how business conflicts in Tysons are typically resolved – whether through the court system (litigation) or outside of it (arbitration, mediation, negotiation) – and the considerations that guide these choices. It also touches on recent trends, such as Virginia’s move toward specialized business courts, aimed at handling complex business cases more effectively.

Litigation in Virginia Courts – Fast and Focused: If a business dispute proceeds in court, Tysons companies have the advantage (or challenge) of litigating in one of the nation’s most efficient legal environments. The local federal court – the Eastern District of Virginia (Alexandria Division) – is famously known as the “Rocket Docket” for its speed, with cases often going to trial within 8–10 months of filing. Even the Virginia state courts in Fairfax County push cases along on a firm schedule, with proactive judges who discourage dilatory tactics. This means that a party suing or being sued in Tysons must prepare early and thoroughly – there is little time for dragging one’s feet. Initial pleadings need to be sharp, discovery (the evidence-gathering phase) is typically on a tight timeline, and courts enforce deadlines strictly. The upside is that a deserving plaintiff can get relief relatively quickly, and a baseless case can be disposed of without years of protracted litigation. The downside is that litigation can become intense and costly quickly, given the need to marshal evidence and brief complex issues promptly.

Virginia courts also employ procedures to streamline business cases. For instance, the Fairfax Circuit Court has a Differentiated Case Tracking Program that assigns cases to fast-track or complex tracks based on their nature and complexity. Recently, the Commonwealth has been piloting a Business and Complex Litigation Docket – a sort of specialized business court within the circuit courts – to handle complex corporate and commercial cases (such as corporate governance, mergers, trade secrets, etc.) more efficiently. Under a 2026 proposal, certain large cases (over $100,000 in controversy and meeting complexity criteria) could be transferred to this docket, overseen by judges with expertise in business law. The goal is to ensure such disputes get the attention and consistency they need. For Tysons litigants, this means your case might be handled by a judge well-versed in business issues, potentially leading to more predictable outcomes. While this program is new, it reflects Virginia’s recognition that complex business disputes sometimes need specialized management – much like Delaware’s renowned Chancery Court, albeit structured differently.

Arbitration – A Common Path in Tysons Contracts: Many Tysons businesses proactively choose arbitration as a dispute-resolution method in their contracts. Arbitration is a private process where disputes are decided by a neutral arbitrator (or panel) rather than a judge, typically in a confidential setting. Why choose arbitration? For one, it can be faster than court (though not always), and it allows the parties to select an arbitrator with expertise in the subject matter (say, a former construction law judge for a construction contract dispute). In the Tysons area, where deals often involve parties from different states or countries, arbitration provides a neutral forum and avoids any “home court” advantage. The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) and Virginia’s own Uniform Arbitration Act (Code § 8.01-581.01) both make written arbitration agreements “valid, enforceable and irrevocable” (save for standard contract defenses). In practice, this means if your Tysons business contract has an arbitration clause, Virginia courts will enforce it and compel arbitration, barring very limited exceptions. As noted earlier, many Northern Virginia contracts involve interstate commerce, so the FAA governs and federal courts will readily send disputes to arbitration.

Arbitration in the Tysons area often happens through organizations like the American Arbitration Association (AAA) or JAMS, with hearings sometimes taking place in Washington D.C. or Northern Virginia conference centers. Arbitration can be tailored – the parties can set rules on discovery, confidentiality, and timelines. Business executives often appreciate that ADR “allows dispute resolution strategies consistent with business objectives”, minimizing the time that key people are pulled away from their work and often achieving results more quickly and cheaply than court. Additionally, arbitration is private; unlike court filings, which are public, arbitration proceedings and awards can be kept confidential, an important factor if reputational concerns or trade secrets are involved. For example, a Tysons government contractor might prefer arbitration to avoid publicizing a dispute that could alert competitors or regulators.

However, arbitration isn’t always the best route. There are drawbacks: arbitration fees can be high (you pay the arbitrator by the hour, whereas judges are free), and there’s no automatic right to appeal an arbitrator’s decision (courts will only vacate an award for very severe issues like fraud or arbitrator misconduct). Moreover, if a party needs immediate court intervention – say, a temporary restraining order (TRO) to prevent the misuse of a trade secret or a breach of a non-compete – arbitration might be too slow or lack the power to enforce such immediate relief effectively. As one Tysons attorney notes, “where there is a need to obtain a TRO or preliminary injunction, to protect a strategic interest, … litigation is usually the best choice”. For instance, if a Tysons software firm discovers that a former employee is about to publicly release its proprietary code, going to a Virginia court for an injunction now is likely preferable to starting arbitration, which could take weeks to organize a hearing. Similarly, if a company wants to establish a legal precedent (perhaps to deter other potential litigants), only a court decision can do that – arbitration awards aren’t precedent for anyone but the parties involved.

Mediation and Negotiated Settlements: Alongside arbitration, mediation is widely used in Tysons to resolve business disputes. Mediation involves a neutral third-party mediator who facilitates settlement discussions between the disputing parties. It’s non-binding – the mediator doesn’t decide the case, but helps the parties find common ground. Many contracts in Northern Virginia include mediation clauses requiring the parties to attempt mediation before filing suit or arbitration. Even without a clause, judges often encourage or order mediation at some stage. The benefits of mediation are numerous: it’s confidential, it allows creative solutions (the parties can agree to business arrangements a court might not order), and it often preserves business relationships that might be destroyed in adversarial litigation. For example, two Tysons business partners parting ways might mediate a buy-out agreement that ends their venture amicably, rather than fighting in court and devaluing the business. Mediation can also be much quicker and cheaper than both litigation and arbitration. In a complex case, the parties might spend a day or two in mediation (for a few thousand dollars) and potentially settle, whereas a full trial could cost each side hundreds of thousands in legal fees.

Practically, in Tysons, there’s a strong culture of trying to settle disputes out of court if possible. Law firms here often tout their ability to handle trials and to negotiate favorable deals. A typical progression might be: a dispute arises, lawyers exchange letters or have a meeting to see if it can be resolved; if not, someone files a lawsuit (or demand for arbitration); then, after some initial discovery or court rulings that clarify the case, the parties engage in settlement talks or mediation. It’s not unusual that, even after filing, most cases settle before reaching trial. Business people usually prefer a certain outcome via settlement over the uncertainty of a trial – as long as the settlement is reasonable. The presence of experienced mediators (often retired judges or lawyers) in the DC metropolitan area means parties have access to skilled facilitators who understand the nuances of business conflicts.

Strategic Considerations: So how should a Tysons company decide between litigation, arbitration, mediation, etc.? Here are a few guiding points:

- Nature of Dispute: If it’s primarily a contractual payment dispute or a technical matter, arbitration might be fine. If it involves vital IP or an urgent need for injunctive relief, a court might be necessary (since arbitrators lack the power to enforce injunctions with the contempt powers of a court).

- Confidentiality: If keeping the matter out of the public eye is important (e.g., a dispute over a product defect that you don’t want customers to know), arbitration or mediation is preferable.

- Speed: Court in EDVA is extremely fast, sometimes faster than arbitration. But state court can be slower (though Fairfax is not too slow, often 12-18 months to trial). Arbitration scheduling depends on the arbitrator’s and parties’ calendars – it can be faster or slower, but you can at least choose a faster track by agreement.

- Costs: Mediation is relatively low cost and should almost always be attempted – its success rate is high enough that it’s worth trying in most business cases. Litigation and arbitration costs can be comparable, but arbitration has upfront costs (admin fees and arbitrator fees) that court does not. On the other hand, tighter discovery in arbitration might reduce legal fees compared to scorched-earth litigation discovery.

- Enforceability: Both court judgments and arbitration awards are enforceable, but arbitration awards require a court confirmation to become a judgment if the loser doesn’t pay voluntarily. Internationally, arbitration awards can be easier to enforce (thanks to treaties like the New York Convention) than court judgments. Tysons companies dealing with foreign partners often include arbitration clauses for this reason.

Increasingly, sophisticated businesses are using hybrid approaches: for example, including an escalation clause in contracts (negotiate first, then mediate, then arbitrate as last resort). Others carve out exceptions: an arbitration clause might say “except that either party may seek injunctive relief in court for misuse of intellectual property.” This ensures that urgent matters can go to court while everything else goes to arbitration.

One should also be aware of settlement techniques like offer of judgment or High/Low agreements. In Virginia state courts, a defendant can make a formal settlement offer; if the plaintiff rejects it and then fails to do better at trial, there can be cost-shifting consequences. Parties sometimes agree to a high/low range during jury deliberations (e.g., regardless of verdict, defendant will pay at least $X and at most $Y), which caps risk and ensures some recovery.

Finally, the personal aspect: Tysons is a big business community, but it can feel small in certain industries (contracting, tech, real estate). Maintaining a good reputation for fair dealing is a long-term business strategy. Engaging in scorched-earth litigation over every slight can backfire, as other companies may become wary of working with a known litigator. Many Tysons businesses quietly settle disputes and even include non-disparagement clauses to prevent conflicts from spilling into the business community. Alternative forums like the Tysons Chamber of Commerce sometimes provide informal dispute resolution or at least networking that can ease tensions.

Key Takeaway: The optimal path for resolving a business dispute in Tysons depends on context, but it’s crucial to evaluate all options early. Smart businesses draft dispute-resolution clauses into their contracts to suit their needs (for instance, requiring mediation, choosing arbitration for certain issues, or specifying the Fairfax courts for any litigation). When a dispute arises, consulting experienced counsel about forum strategy can save time and money. In some cases, litigation in Virginia’s efficient courts will be the right call – especially if you need a fast, enforceable judgment or an injunction. In others, a discreet ADR solution will protect relationships and secrets while yielding a business-oriented result. The good news is that Tysons companies have a full toolbox of dispute-resolution mechanisms at their disposal, and a legal environment that supports their use. The approach should be tailored to the dispute’s specifics and the company’s goals – whether it’s preserving a partnership, sending a message, or simply getting compensated for a loss with minimal fuss. Ultimately, an “accessible and useful” dispute resolution strategy is one that resolves the matter favorably and keeps the business moving forward despite the hiccup.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

- Virginia Statutes

Code of Virginia § 8.01-246 (2023) – Personal action for breach of contract (written contracts: 5-year limitation; unwritten: 3-year).

Code of Virginia § 8.01-247.1 (1995) – Defamation (libel, slander) 1-year limitation.

Code of Virginia § 8.01-581.01 (1986) – Validity of arbitration agreements (Uniform Arbitration Act).

Code of Virginia § 8.01-581.02 (1986) – Proceedings to compel or stay arbitration.

Code of Virginia § 8.01-38.1 (1987) – Punitive damages cap ($350,000).

Code of Virginia § 8.2-725 (1964) – UCC sale of goods contract, 4-year limitation period.

Code of Virginia §§ 18.2-178, -181, -111 (1950) – Crimes of false pretenses, bad checks, embezzlement (fraud-related).

Code of Virginia §§ 18.2-499, -500 (1968) – Business conspiracy statute (treble damages for willful, malicious injury to business).

Code of Virginia § 50-73.102 (1996) – Partnership duties of loyalty and care among partners.

Code of Virginia § 13.1-724 (1985) – Shareholder approval required for sale of substantially all corporate assets (2/3 vote, protecting minority).

Code of Virginia § 13.1-747 (1985) – Judicial dissolution of a corporation for illegal, oppressive or fraudulent acts by controllers.

Code of Virginia § 59.1-336 to -343 (1986) – Virginia Uniform Trade Secrets Act (civil remedies for misappropriation).Virginia Case Law

Abi-Najm v. Concord Condominium, LLC, 280 Va. 350, 699 S.E.2d 483 (2010) – Fraud must be based on present fact; false promises or predictions are not actionable as fraud.

Almy v. Grisham, 273 Va. 68, 639 S.E.2d 182 (2007) – Business conspiracy requires an underlying tort; conspiracy claim fails without an actionable wrong.

Augusta Mutual Ins. Co. v. Mason, 274 Va. 199, 645 S.E.2d 290 (2007) – Fiduciary duty exists only with special trust; no separate fiduciary tort if duty arises solely from contract.

Chaves v. Johnson, 230 Va. 112, 335 S.E.2d 97 (1985) – Defined elements of tortious interference with contract (valid contract, knowledge, intentional interference, improper methods, damage).

Commercial Business Systems, Inc. v. Halifax Corp., 253 Va. 292, 484 S.E.2d 892 (1997) – Tortious interference with business expectancy requires a probable future economic benefit, not mere hope.

Colgate v. Disthene Group, Inc., 82 Va. Cir. 169 (2011) (Cir. Ct. Buckingham Cty.) – Court ordered dissolution of corporation due to majority’s oppressive, fraudulent conduct toward minority.

Countryside Orthopaedics, P.C. v. Peyton, 261 Va. 142, 541 S.E.2d 279 (2001) – Contracts must be terminated per their terms; failure to follow contractual notice/cure procedure invalidated termination.

Duggin v. Adams, 234 Va. 221, 360 S.E.2d 832 (1987) – In tortious interference, competition is not an improper method; improper methods include violence, fraud, unethical conduct, etc..

Filak v. George, 267 Va. 612, 594 S.E.2d 610 (2004) – Defined breach of contract elements; established “source of duty” rule (no tort recovery for purely contractual duties).

Flippo v. CSC Associates III, L.L.C., 262 Va. 48, 547 S.E.2d 216 (2001) – LLC operating agreements can modify fiduciary duties; managers’ actions judged in light of business judgment rule if done in good faith for company’s benefit.

Fox v. Deese, 234 Va. 412, 362 S.E.2d 699 (1987) – Intracorporate immunity: a corporation and its agents acting within scope are one entity and cannot conspire with themselves.

Lewis-Gale Medical Center, LLC v. Alldredge, 282 Va. 141, 710 S.E.2d 716 (2011) – Reinforced that lawful competition is not tortious; interference claims require improper conduct (protected competition vs. improper acts).

May v. R.A. Yancy Lumber Corp., 297 Va. 1, 822 S.E.2d 358 (2019) – Majority shareholders’ attempt to bypass statutory requirement (supermajority vote for asset sale) by bylaw amendment was struck down; statute protects minority.

Mortarino v. Consultant Engineering Servs., Inc., 251 Va. 289, 467 S.E.2d 778 (1996) – Fraud claims require specific factual misrepresentation; courts reject fraud allegations that are merely breaches or lack detail.

Pocahontas Mining LLC v. CNX Gas Co., 276 Va. 346, 666 S.E.2d 527 (2008) – Virginia adheres to the plain meaning rule in contracts; unambiguous terms are enforced as written.

Simmons v. Miller, 261 Va. 561, 544 S.E.2d 666 (2001) – Defined legal malice for conspiracy (intentional act without lawful justification to harm); also held that fiduciary duty claims by shareholders for corporate injury must be brought derivatively.

Station #2, LLC v. Lynch, 280 Va. 166, 695 S.E.2d 537 (2010) – Fraud must involve misrepresentation of present fact, not unfulfilled promises; clarified promissory fraud standard (intent not to perform at time of promise required).

Today Homes, Inc. v. Williams, 272 Va. 462, 634 S.E.2d 737 (2006) – Corporate officers breached fiduciary duty by diverting a corporate opportunity; established that taking business opportunities for oneself violates duty of loyalty.Secondary Sources

Berlik, Lee E. (n.d.). Tysons Corner Information. BerlikLaw LLC. Retrieved January 17, 2026, from https://www.berliklaw.com/tysons-corner-information.html .

BerlikLaw (n.d.). Mediation and Arbitration. Retrieved January 17, 2026, from https://www.berliklaw.com/mediation-and-arbitration.html .

General Counsel, P.C. (2021). Minority Shareholder Protections (Blog article). Retrieved January 17, 2026, from https://generalcounsellaw.com/minority-shareholder-protections/ .

Price Benowitz LLP (n.d.). Virginia Partnership Disputes Lawyer – Laws Concerning Partnerships in Virginia. Retrieved January 17, 2026, from https://pricebenowitz.com/virginia-commercial-litigation-lawyer/business/partnership-disputes/ .

Shin, Anthony I. (2023). Ultimate Guide to Business Litigation in Northern Virginia. Shin Law Office (Blog). Retrieved January 17, 2026, from https://shinlawoffice.com/ultimate-guide-to-business-litigation-in-northern-virginia/ .

Simms, Jonathan (2017, June 15). Statutes of Limitations (Simms Firm Blog). Retrieved January 17, 2026, from http://simmsfirm.com/statute-of-limitations/ .

U.S. Office of Justice Programs (1993). Rocket Docket (NCJ 142176, R.H. Glover, Trial v.29, no.4). Summary retrieved from https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/rocket-docket .