Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

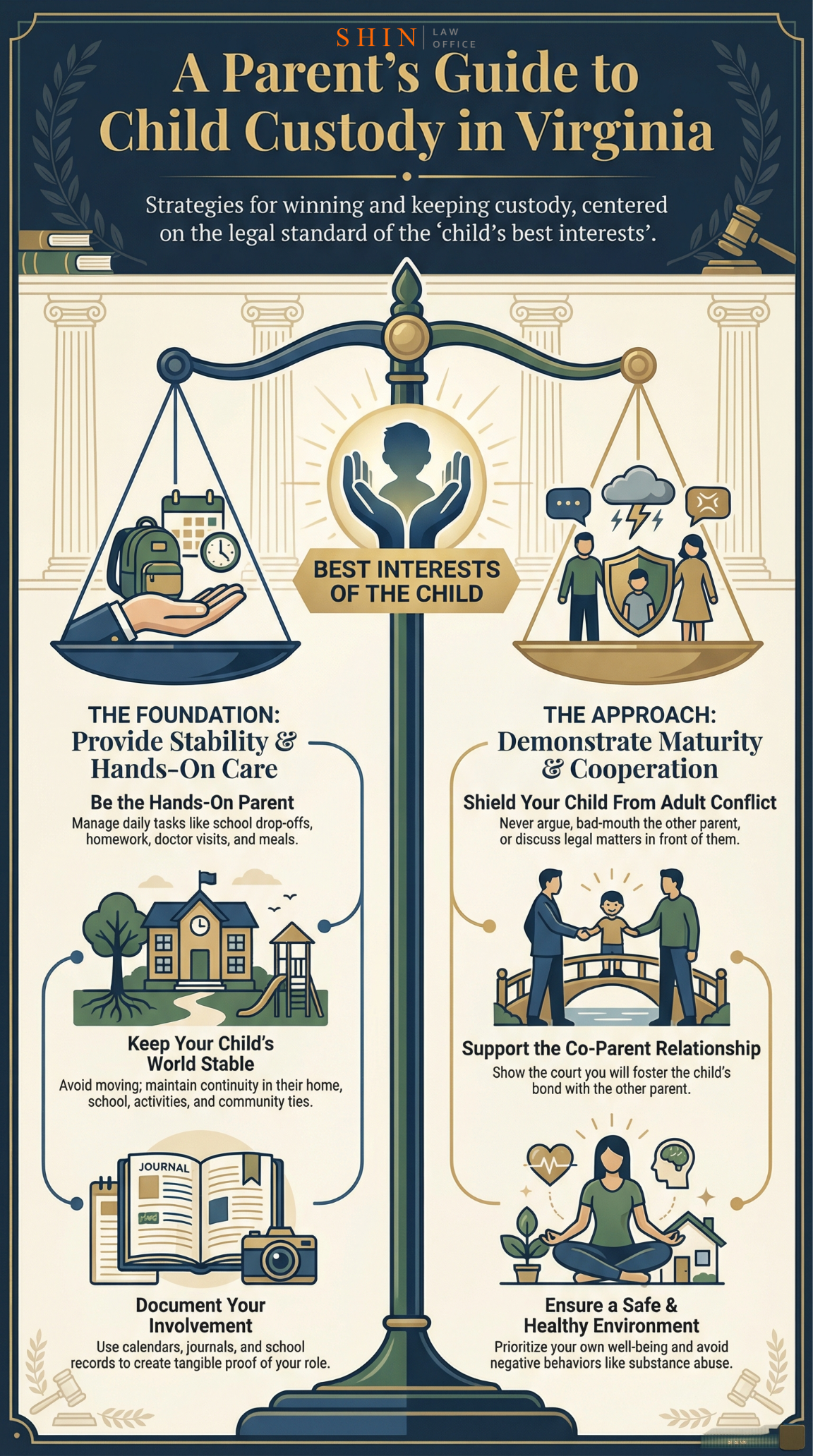

Divorcing parents in Northern Virginia must focus relentlessly on the “best interests” of their children to maximize their chances of retaining custody. In practice, this means providing stability, maintaining strong bonds, and demonstrating cooperative co-parenting at every step. Virginia law (Code § 20-124.3) sets out ten factors judges consider in custody decisions, ranging from each parent’s caregiving role to the child’s needs and any history of abuse.

The bottom line: Courts want to see which parent can offer the most stable, loving, conflict-free environment for the children. In this guide, I draw on my experience as a Northern Virginia family attorney to break down 20 effective strategies – from being the primary caregiver to avoiding toxic conflict – that have helped my clients in Fairfax, Loudoun, Arlington, Prince William, Clarke, and Frederick counties win and keep custody. Each chapter provides real-world insights (with hypothetical examples from places like Leesburg, Fairfax City, Arlington, Manassas, Berryville, and Winchester) and references Virginia law, local court practices, and key cases.

Whether you’re in bustling Fairfax or rural Clarke County, the principles remain the same: put your children first, and be the parent that the evidence shows is best for them. This comprehensive 20-chapter guide will help you do exactly that.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Virginia’s Custody Factors – Laying the legal groundwork (Code § 20-124.3) for what courts evaluate.

- Embracing the Primary Caregiver Role – Why day-to-day parenting duties give you an edge.

- Maintaining a Stable Home Environment – Providing consistency in residence and routine.

- Prioritizing Educational Continuity – Keeping kids in their current schools and activities.

- Avoiding Unnecessary Relocation – Staying put in Northern Virginia to preserve stability.

- Shielding Children from Conflict – Keeping adult disputes and stress away from the kids.

- Supporting the Co-Parent Relationship – How encouraging your child’s bond with the other parent helps your case.

- Leveraging Extended Family and Community Ties – Keeping kids connected with siblings, grandparents, and community.

- Staying Actively Involved in Your Child’s Life – Showing up for school, health, and extracurricular needs.

- Documenting Your Parenting Involvement – Using journals, calendars, and evidence to tell your story.

- Aligning Your Schedule with Your Child’s Needs – Balancing work and life to be there when it counts.

- Prioritizing Parental Fitness and Health – Caring for your mental and physical well-being.

- Avoiding Negative Habits and Behaviors – Steering clear of substance abuse, legal trouble, and online pitfalls.

- Ensuring a Safe, Abuse-Free Environment – Why any history of abuse can override all other factors.

- Respecting Court Orders and Procedures – Following local rules, temporary orders, and required parent education.

- Working with Guardians ad Litem and Evaluators – Cooperating with court-appointed advocates and experts.

- Utilizing Mediation and Settlement Opportunities – Showing reasonableness by negotiating where possible.

- Establishing a Favorable Status Quo – Managing separation so that the “current normal” favors your custody goals.

- Considering Your Child’s Voice – Handling an older child’s custodial preferences appropriately.

- Tailoring Your Case to Best Interest Factors – Proactively addressing each of Virginia’s custody factors in your strategy.

- References

Chapter 1: Understanding Virginia’s Custody Factors

I always begin by educating my clients on what Virginia law considers in custody cases, because you can’t craft a winning strategy without knowing the rules of the game. In Virginia, courts decide custody based on the “best interests of the child”, guided by ten specific factors listed in Code § 20-124.3. These factors include each parent’s age and health, the child’s developmental needs, the relationship of each parent with the child, the role each parent has played in the child’s upbringing, each parent’s willingness to support the child’s relationship with the other parent, the child’s preference (if old enough), any history of abuse, and other factors the court deems relevant. Importantly, Virginia law does not favor mothers over fathers (or vice versa) – there is no automatic presumption for either parent. Similarly, there’s no de jure presumption that the “primary caregiver” automatically wins custody – the court must consider the whole picture.

In Northern Virginia jurisdictions such as Fairfax and Loudoun, judges apply the same state-law criteria, but each court may have its own procedural nuances. For example, Fairfax County courts typically require parents to attend a parenting education seminar early in the process (a statewide mandate under Va. Code § 16.1-278.15) and often encourage mediation before a trial. Meanwhile, all courts (whether in Arlington, Prince William, or even smaller ones like Clarke and Frederick) will expect you to present evidence factor-by-factor. In practice, this means you should be ready to show the judge, for each of the § 20-124.3 factors, why living primarily with you serves your child’s best interests. I often prepare a checklist with clients addressing each factor – e.g., evidence of our positive involvement in the child’s life (factor 3), examples of how we have supported the child’s relationship with the other parent (factor 6), and so on.

One key principle is that Virginia courts favor arrangements that ensure children have frequent and continuing contact with both parents, when appropriate. The law explicitly encourages parents to share in child-rearing responsibilities. From the start, present yourself as a cooperative, child-focused parent, not someone trying to cut out the other parent without good cause. In the chapters that follow, I’ll delve into specific strategies – each tied to these legal factors – that can make the difference in a close case. But remember, everything comes back to demonstrating best interests: show the court that you are the parent best able to meet your child’s needs, ensure their safety, and promote their well-being in every sense.

(Legal reference: Va. Code Ann. § 20-124.3 lists the best interest factors; Va. Code Ann. § 20-124.2 emphasizes no presumption favoring either parent and the policy of frequent contact with both parents. Key case: Brown v. Brown (Va. App. 1999) – reiterating that courts have broad discretion to determine best interests after considering all statutory factors.)

Chapter 2: Embracing the Primary Caregiver Role

Early in my practice, I handled a custody case in Leesburg (Loudoun County) where the father had been the family’s primary breadwinner and the mother the primary caregiver for their two young children. When divorce loomed, the mother’s day-to-day involvement with the kids became a pivotal advantage in court – she knew the pediatrician’s name, the kids’ favorite foods, their homework routines, all the little details. Courts do give significant weight to which parent has been the child’s primary caregiver, even though it’s not an automatic trump card. Virginia judges will ask: Who actually takes the kids to school? Who helps with homework, packs lunches, takes them to soccer practice, and tucks them in at night? The answers to those questions can strongly influence the outcome.

So, if you’re planning a divorce and want custody, strive to either maintain or assume the primary caregiver role well before any court hearing. This may require adjusting your work schedule or personal commitments to accommodate school drop-offs, attend parent-teacher conferences, and manage bedtime routines. I often advise clients in Fairfax or Arlington to start a journal of daily caregiving tasks – not only to remind themselves of all they do, but also to use as evidence if needed. For instance, in one Arlington case, my client (a father) kept a detailed calendar of every day he fed the kids, helped with virtual schooling, and took them to doctor appointments while the mother traveled for work. By trial, it was clear he had been acting as a true co-equal (if not primary) caregiver, which countered the mother’s claims that she was the only one who really knew the children’s needs.

Being the primary caregiver ties directly into at least two of Virginia’s statutory factors: “the role each parent has played and will play in the future in the upbringing and care of the child,” and “the relationship between each parent and the child, including the parent’s positive involvement in the child’s life and ability to meet the child’s needs.”. If you have historically done most of the hands-on care, highlight that involvement – through your testimony, witnesses (babysitters, teachers, neighbors who’ve observed you with the kids), and even photos or school records (e.g., who is listed as the emergency contact). If you haven’t been the primary caretaker historically (perhaps due to work or other circumstances), now is the time to step up. Courts recognize when a parent makes a good-faith effort to increase involvement. But be genuine – judges can tell the difference between someone who suddenly shows up at every dance practice for appearances and someone who is sincerely adapting their life to put the children first.

One caution: while being the primary caregiver is a significant advantage, Virginia courts will still consider all other factors. I’ve seen a case in Manassas (Prince William County) where the mother was clearly the primary caregiver, but due to concerns about her mental health (and evidence the children were doing poorly in her chaotic household), the father won primary custody. The lesson is to embrace the caregiver role while ensuring you meet the child’s needs effectively. If you’re overwhelmed, seek help (family, counselors, etc.) rather than neglecting the child’s needs. Being the primary caregiver only helps you if you’re doing a good job at it. Fortunately, the very fact that you are deeply involved usually means you understand your child’s needs well. So use that knowledge: when you get to court, be prepared to articulate specifics – e.g., “I ensure Emma takes her asthma medication daily and I’ve coordinated with her school nurse about it” or “I arranged Billy’s tutoring when he struggled with reading, and his grades have improved under my watch.” Show that you are not just present, but proactively attentive to your child’s well-being.

(Insight: Courts in Northern Virginia (like Loudoun and Fairfax) often find the primary caregiver has an “inside track” on custody, since that parent can point to countless examples of meeting the child’s daily needs. However, there is no automatic rule – judges must weigh all factors. It’s critical to pair your primary caregiver status with evidence of a healthy, supportive environment for the child.)

Chapter 3: Maintaining a Stable Home Environment

Not long ago, I had a case in Winchester (Frederick County) involving a divorcing couple who, during separation, shuffled their two kids between three different apartments in the span of a year. By the time we got to court, the judge was clearly concerned about the lack of stability. Virginia courts strongly value continuity and stability in a child’s home life. In fact, one Northern Virginia attorney’s guide aptly noted that “Courts strongly value continuity. The parent who remains in the home, maintains school placement, and preserves the child’s daily routine often begins with an advantage.”. I couldn’t agree more. If you can keep the children in their familiar environment – meaning the same house or at least the same community – throughout the divorce process, you’re scoring major points on the “stability” front.

So how do you use this to your advantage? First, avoid sudden moves or drastic household changes if possible. If you’re still in the marital home in Fairfax or Arlington, and you can safely stay there with the kids until the custody is resolved, do so. Leaving the home not only disrupts the children’s routine but can also inadvertently create a new “status quo” where the other parent is the one staying with them in the primary home (more on status quo in Chapter 18). I often counsel clients: unless there’s an unsafe situation, think twice before moving out and taking the kids to a new residence, or worse, leaving them behind. Judges notice which parent kept the children’s living situation stable during the tumult of separation.

Stability isn’t just about the physical dwelling – it’s also about daily routines and caregiving consistency. Maintaining the same bedtime, mealtime, and homework routines can reassure children and demonstrate to the court that you prioritize consistency. For example, if every morning you take your child to the Starbucks on King Street in Alexandria before school because that’s your ritual, keep that up. Continuity in those little rituals means a lot to kids. In a Loudoun County case, my client argued that, even after the other parent moved out, she maintained Saturday as “family pancakes day,” as it had been before, to give the children a sense that not everything was changing. We presented testimony and drawings the kids made about Pancake Day, which underscored her commitment to preserving normalcy.

Another aspect of a stable environment is financial and housing stability. While Virginia law doesn’t let a parent “buy” custody with a fancier home, the court will consider whether each parent can provide adequate housing. You don’t need a mansion in Great Falls to win custody, but you do need to show your living situation is appropriate for the children. This means having a separate bedroom for them if possible, or at least a safe, clean, and child-friendly space. I represented a father from Berryville (Clarke County) who lived in a modest two-bedroom rental; we took photos of the kids’ bedroom, decorated with their favorite posters, and of the backyard, where he set up a swing set. Those exhibits demonstrated that, even on a tight budget, he provided a stable, loving home. The judge in Berryville commented that the children seemed “very much at home” in both households – a positive for both sides – and that the father had done well to maintain stability despite the divorce.

Finally, minimize changes in caregivers. If your children are used to a certain daycare provider, relative, or babysitter, try to keep that consistent too. In one Fairfax case, the mother abruptly replaced the children’s longtime nanny simply because the nanny had originally been hired by the father’s side of the family. That change backfired; the court questioned why the mother disrupted a stable childcare arrangement out of personal resentment. It reflected poorly on her decision-making. The takeaway: judges don’t like to see children used as pawns or their routines upended unnecessarily. Show that you put the kids’ stability first, even when it might be inconvenient for you.

(Real-world tip: In many Northern Virginia courts, I’ve observed judges lean towards the parent who can demonstrate greater stability in living conditions and routine. For example, remaining in the family home in Arlington or keeping the children in the same Leesburg neighborhood can give you an edge. Stability equates to security for a child, and a secure child is more likely a happy child, which is ultimately what every judge wants to achieve.)

Chapter 4: Prioritizing Educational Continuity

If there’s one thing Northern Virginia parents know, it’s how important our local schools are – whether it’s a public school in Fairfax County, a private academy in McLean, or even a tight-knit elementary in Berryville. Judges know it too. Maintaining continuity in a child’s education is a powerful custody strategy. Uprooting a child from their school without a compelling reason can be viewed as disruptive to their best interests. In fact, continuity of schooling and community is often wrapped into the “needs of the child” factor in Virginia law, which considers the child’s relationships with peers and involvement in their community.

In my Loudoun County case mentioned earlier, one reason the mother prevailed was that she planned to remain in the same school pyramid so the children wouldn’t have to change schools, whereas the father was considering moving them to a different district. The judge explicitly noted the benefit of the children remaining at Leesburg Elementary with their friends during a difficult time. Similarly, I handled a case in Fairfax City where both parents lived within the Fairfax High School district, but the father’s proposed visitation schedule would have had the kids shuttling to another county during the week (due to his temporary residence with relatives). We argued – and the court agreed – that the mother’s plan, which kept the children sleeping in their own beds on school nights and attending their same extracurriculars at Fairfax High, was more stable for their education.

So how can you leverage educational stability? First, try to remain in your child’s current school district or zone. If you anticipate divorce, think twice about any plans to move to a new county or even a different part of the same county if it means a school change. I’ve seen a parent in Prince William County (Manassas area) delay a planned move to another state until the custody matter was resolved, specifically to avoid giving the impression she was removing the children from their schools. It paid off – by showing that commitment, she secured primary custody and later arranged the move with court approval (with careful planning to minimize disruption).

Second, highlight your involvement in the child’s education to demonstrate continuity. Are you the parent who helps with homework every night? Do you meet with teachers, attend school concerts, volunteer for the PTA or school events? Document it and be prepared to discuss it. A parent who is deeply engaged in the child’s schooling demonstrates not only continuity but also the ability to meet the child’s intellectual and developmental needs (factors 3 and 4 in the law). I often submit as evidence items such as copies of signed report cards, emails between the parent and teachers, or photos from the school science fair where my client was present. In one Arlington case, my client kept a log of every time she communicated with her son’s school counselor about his progress; that log helped show the judge how invested she was in keeping him on track academically.

Third, consider the child’s extracurricular activities and friendships, which extend beyond school life. Northern Virginia kids tend to be very involved – whether it’s soccer in Ashburn, debate club in Falls Church, or Scouts in Winchester. Keeping those activities consistent matters. If one parent’s custody plan would force the child to quit travel soccer or drop out of band because of logistical conflicts, while the other parent’s plan allows the child to continue unabated, the court will likely favor the latter. I recall a case in Herndon where the judge was swayed by the fact that the mother’s custody proposal let the middle-school daughter keep attending her advanced math tutoring and Girl Scouts meetings, whereas the father’s long-distance move would have made that impossible.

Sometimes, achieving educational continuity might require creative solutions. For example, both parents could agree to keep the child at the same private school and split the tuition, or one parent could agree to handle all transportation so the child can stay at their school even if the parent lives slightly outside the zone. Showing flexibility and willingness to cooperate for the child’s educational benefit will reflect positively on you. I’ve brokered agreements where a parent promised to drive 45 minutes each morning just to keep the kids at Clarke County High School through the end of the year – that level of commitment impressed the court as putting the kids first.

In summary, courts in our area place a premium on not rocking the boat academically. A divorce is already disruptive; if you can be the parent who minimizes disruption in school life, you’re aligning yourself with the child’s best interests. Emphasize that with you, the child will wake up in the same bed, catch the same school bus, see the same teachers and friends, and stick to their usual after-school routine, despite the divorce. That’s a compelling narrative to a judge. After all, a child who is able to focus on learning and friends – rather than adjusting to a new school or routine – is more likely to thrive during the upheaval of a family split.

(Practice pointer: Judges frequently mention the value of keeping children in the same school and community during custody cases. Stability in education and peer relationships is part of the child’s overall needs. One local guide notes that the parent who “maintains school placement” often gains an advantage. In short, if you can credibly tell a Loudoun or Fairfax judge, “Your Honor, under my care nothing in Johnny’s school life will change,” you’re scoring big in the best-interests analysis.)

Chapter 5: Avoiding Unnecessary Relocation

One of the most common pieces of advice I give to parents in Northern Virginia is “stay put if you can.” This region is transient, with many families moving in and out for jobs (think government or military). But if you are aiming for custody, relocating out of the area – or even far enough to disrupt the other parent’s access – can seriously jeopardize your case. Virginia courts have made it increasingly hard for a custodial parent to relocate a child over the other parent’s objection. As a result, a parent who signals plans to move away may be viewed as putting their own interests above the child’s need for stability and relationship with both parents.

I had a case in Fairfax where the mother wanted to move with the children to North Carolina to be closer to her extended family. The father adamantly opposed it. I represented the father, and we successfully argued that the relocation was not in the children’s best interests. We cited how the move would remove the kids from their father’s daily life and how they were thriving in their current Fairfax community. The judge referenced the principle that “the test is whether relocation is in the child’s best interests, not the parent’s.” Indeed, Virginia law requires that a relocating parent prove the move will benefit the child, not just themselves. That’s a high bar. In practice, this means unless you have a clear, child-centered reason – like a move that brings the child closer to important extended family who help care for them, or perhaps access to a special education resource – relocation can be a tough sell.

For parents planning a divorce, the strategic move is: don’t move out of Northern Virginia (or even out of your county) while custody is being determined, unless absolutely necessary. If you anticipate relocating eventually, it’s often wiser to secure custody under the status quo first and then seek court permission later, rather than moving preemptively and risking losing custody. In one Arlington case, my client (the mother) had a job offer in Texas. We decided she would turn it down and stay through the custody trial; she won primary custody in Arlington, largely because she was the stabilizing parent. A year later, we petitioned for relocation with a detailed plan and evidence of the child’s best interests (including proximity to maternal grandparents in Texas and enrollment at a top school there). That was a separate uphill battle, but we had a much better chance since she already had custody. By contrast, I observed another case in which a father moved to California during his divorce proceedings. By the time of trial, the mother had de facto primary care in Virginia, and the court wasn’t about to uproot the child to the West Coast to live with a parent who’d effectively withdrawn.

Now, sometimes relocation is unavoidable. Perhaps you have military orders or a job transfer that you cannot refuse. In such cases, tread carefully and build the strongest possible case that the move benefits the child. This includes specifics: show the court exactly what life will look like in the new location. What school will the child attend? Is it as good as or better than the current one? Will you be near supportive family? How will you facilitate the child’s relationship with the other parent – e.g., paying for monthly flights, providing virtual visitation, summers back in Virginia, etc.? In a Clarke County case, a mother relocated to Atlanta for work. She put together a comprehensive “relocation plan” that impressed the judge: she had already lined up a house in a neighborhood with top-rated schools, secured a spot for the child in a gifted program, and proposed a visitation schedule that gave the father all summer and long school breaks, plus Skype calls three times a week. She even offered to pay travel costs. This level of preparation demonstrated to the court that she was considering the child’s welfare, not just her own wishes.

On the flip side, if you are the parent opposing a potential relocation by your ex, you should document how involved you are in your child’s life (the more involvement, the stronger your argument that a move would harm the relationship). Virginia courts look at how drastically the move would affect the non-custodial parent’s visitation and the current level of involvement. In one case in Loudoun County, I represented a father who was very active with his kids – coaching their Purcellville Little League and never missing a weekend. When the mother proposed moving the kids to Richmond, we emphasized that his relationship would be “substantially impaired” by the distance. The court agreed, warning that if she moved, she might lose custody to him. She ultimately stayed.

It’s worth noting a recent Virginia Court of Appeals case, Brandon v. Coffey (2023), which clarified that for initial custody decisions, a judge doesn’t have to make a separate finding that out-of-state placement is in the child’s best interest so long as all best-interest factors are considered. In other words, if at the initial custody trial one parent already lives out of state, the court applies the standard best-interest test without a separate “relocation” analysis. However, if a relocation comes up after an initial order (in a modification context), courts do scrutinize it closely. The practical takeaway for initial cases is: even if you already live outside Virginia (say, one parent stayed in Winchester and the other moved to Maryland during separation), the court can still award custody to the out-of-state parent – but only if overall best interests favor that parent. The in-state parent might argue the move is inherently not in the child’s interest, but Brandon says there’s no extra hurdle at that stage beyond the regular factors. Of course, one of those regular factors is the impact on the child’s relationship with each parent, which inherently covers the distance issue.

In summary, if you want to retain custody in Northern Virginia, think carefully before relocating. Generally, staying local strengthens your case by preserving the child’s community ties and the other parent’s access. Judges see a parent who stays as prioritizing the child’s stability. If you must move, plan it as if you’re presenting a business proposal to an investor – except here the “investor” is the judge, and the “business” is your child’s life. Every detail counts, and the focus must be on the child’s gains, not yours.

(Case law highlight: Virginia courts often side with the non-relocating parent, absent a clear benefit to the child. In Cloutier v. Queen (Va. App. 2001), a mother’s request to move the child was denied; the court noted that the father was deeply involved daily and the current environment was positive. The evidence showed the children were doing well socially and academically with their father present, so the court wouldn’t risk harming that bond. The lesson from cases like Cloutier is that relocation will likely be blocked if it undermines a thriving parent-child relationship. Conversely, any relocation argument must convincingly show the child will be better off, not just equally okay.)

Chapter 6: Shielding Children from Conflict

In the midst of a divorce, emotions run high – anger, frustration, grief. It’s easy (and human) for those feelings to spill over. But one of the cardinal rules of custody battles is this: Do not drag your children into adult conflicts. Judges are acutely aware of the damage that parental conflict can do to kids, and if they suspect you’re exposing the child to fights or bad-mouthing, it can hurt your custody case. Virginia’s best-interest factors explicitly include “the propensity of each parent to actively support the child’s contact and relationship with the other parent,” which covers not only facilitating visits but also avoiding poisoning the well with conflict. Additionally, judges consider each parent’s willingness and ability to cooperate for the child’s sake. If you’re fighting in front of the kids, you’re basically proving that you’re not putting their emotional well-being first.

I often use a real-world example: In a Fairfax case, two parents would routinely exchange heated insults at pickup and drop-off while their 8-year-old son stood right there. By the time I got involved, that child was having anxiety attacks every Sunday night before transitions. We worked hard to change my client’s behavior – I coached him to keep exchanges brief and calm, even if the other parent tried to provoke him. In court, the mother tried to claim the father was “uncooperative,” but we brought in the child’s therapist who testified that once the father stopped engaging in arguments at exchanges, the boy’s anxiety symptoms improved. The judge took note that the father made an effort to shield the child from conflict, which aligned with being the more child-centric parent.

Never argue, shout, or discuss litigation details in front of your children. This includes on the phone if they might overhear, or within the home where kids might be listening behind doors. In the age of technology, it also means don’t text or email vicious diatribes that your savvy teenager might stumble upon. I had a case in Arlington where a teen inadvertently read his dad’s court papers left on the kitchen table, which included nasty allegations about the mom. It was devastating for the child and infuriated the judge – the father was deemed careless with the child’s emotional safety.

Another form of conflict exposure is using the child as a messenger or spy. For example, telling your child “ask your mom why she’s ruining our family” or interrogating the child about the other parent’s personal life is a huge no-no. Not only can kids say things in court (through a guardian ad litem or evaluator) about this behavior, but it’s also often evident in their demeanor. A child caught in the middle might become withdrawn, act out, or parrot adult phrases. Judges (and GALs) are trained to spot signs of parental influence or stress from conflict.

Virginia judges appreciate parents who take the high road. As a strategy, demonstrate that you are the parent who promotes a calm, loving environment, free from adult drama. Specifically, this can mean agreeing to a structured communication method with your ex (such as a parenting app or email) to reduce direct confrontation. It might mean suggesting curbside pickup or meeting at a neutral location in Manassas or Leesburg to reduce the risk of arguments. In one Winchester case, the parents agreed to do exchanges at the parking lot of the Winchester police station – not because anyone was violent, but simply because both felt they’d “behave” better in public. It worked; they were civil, knowing officers were nearby, and over time, they improved their communication.

Importantly, never involve your children in choosing sides. Even if your teenager has opinions (covered more in Chapter 19 on children’s voice), you should never explicitly or implicitly pressure them to favor you. I often tell clients: Assume everything you say or do in front of your kids will be replayed in a courtroom. If the thought of a judge hearing you scream, “Your dad’s a deadbeat!” at your child makes you cringe, then don’t do it. Better yet, imagine a video of that moment being played – because sometimes, indeed, there are recordings. (Yes, in a few cases I’ve seen, older kids have recorded parental tirades on their phones.)

On the positive side, make your home a refuge from the divorce. Let your children be kids. Continue normal routines and reassure them that both parents love them. If they bring up the other parent, speak neutrally or kindly. This can be hard, I know. One client in Fairfax City was furious at how her ex cheated on her, but she practiced saying neutral phrases like “Daddy loves you” when the kids asked why Daddy wasn’t around. She vented plenty in our private meetings and therapy, but she never let the kids see her hatred. The reward? A psychologist evaluator in the case reported that she found Mom was doing an excellent job insulating the children from adult issues, whereas Dad had made a few snide comments that the kids repeated. The court ultimately gave Mom primary physical custody, in part because she was better at “fostering a positive emotional environment” for the children.

The bottom line: Courts favor the parent who keeps conflict away from the children. If you have a lapse and something happens – say a shouting match that the kids witness – it’s not game over, but you should address it. Perhaps apologize to the children in an age-appropriate way (“Mom and Dad are sorry you heard us argue. We’re going to try to do better.”) and then do better. If there’s evidence of ongoing conflict exposure, a judge could even order you to take a co-parenting class or therapy. Better to pre-empt that: show that you are proactively managing conflict. Sometimes I even advise clients to voluntarily enroll in a co-parenting or anger management course and bring the completion certificate to court to demonstrate their commitment to improvement.

(Evidence in action: Virginia law’s Factor 6 stresses a parent’s support for the child’s relationship with the other parent. Courts view negatively any behavior like bad-mouthing or involving the child in disputes. A Richmond-area firm’s blog noted that attempts to alienate or undermine the other parent – such as speaking poorly about them or blocking visits – are major red flags to judges. In practice, I’ve seen judges in Loudoun and Prince William “flip” custody when one parent chronically exposes the kids to conflict and denies visitation without cause. They would rather place the child with the parent who shields them from the battle, underscoring how vital it is to keep your war with your ex away from the kids.)

Chapter 7: Supporting the Co-Parent Relationship

This chapter’s advice often surprises clients at first: One of the best ways to demonstrate you’re the right parent is to respect and nurture your child’s relationship with their other parent. In other words, even as you’re fighting for custody, you must show the court that you understand the child benefits from having both parents in their life. This can feel counterintuitive – you’re divorcing for a reason, and you probably have plenty of grievances against your ex. But Virginia law explicitly looks at each parent’s “propensity… to actively support the child’s contact and relationship with the other parent.” If the judge thinks you would shut out the other parent or poison the child’s mind against them, that’s a serious strike against you. Conversely, being cooperative and positive about the other parent can tilt things in your favor.

Let me share a story from Leesburg (Loudoun County). I represented a father who was very bitter about how his marriage ended. The mother had had an affair, and he was, understandably, angry. In our early meetings I noticed he would call her nasty names (never in front of the kids, thankfully). I told him: “You have every right to be upset, but save it for therapy or our private talks. In front of your daughter – and in front of the judge – you need to be the bigger person who still recognizes Mom is important to your child.” He took that to heart. When he testified, he made a point of saying things like “She’s a good mother in many ways” and “I want our daughter to have a great relationship with her mom, absolutely.” I could see the judge’s demeanor soften because he came across as reasonable and child-focused. Meanwhile, the mother couldn’t resist throwing in jabs like “He’s never been around anyway,” and she looked petty by comparison. We won primary custody for the father. After the hearing, the judge specifically commended the father for his “mature approach” to co-parenting and noted that he appeared more likely to facilitate the child’s relationship with both sides of the family.

So, what are concrete ways to show your support for the other parent-child relationship?

- Facilitate visitation and contact: Be punctual and flexible with exchange times. If your ex requests a minor change (like switching weekends for a special event), consider agreeing. Keep a record if you like – I sometimes present a log of instances where my client accommodated the other parent. It shows the judge a pattern of cooperation. In Prince William County (Manassas), I’ve seen judges ask, “How do you handle changes in the schedule?” to gauge flexibility and reasonableness.

- Encourage communication: If your child is young, make sure they call or FaceTime the other parent during your time, especially on the other parent’s birthday or on special occasions. A parent who encourages those calls looks very good. If the child is older, at least don’t block their communication. In one Fairfax case, the teenage son testified (through a GAL) that his mom would take away his phone when he was at her house so he couldn’t text his dad. That move backfired badly – the court saw it as controlling and not supportive of the father-son bond.

- Speak positively (or at least neutrally) about the other parent. We touched on this in Chapter 6: avoid bad-mouthing. Take it a step further – find little ways to affirm the other parent’s role. For example, “Your mom is really good at helping you with math, why don’t you ask her to give you extra help on your homework?” or “I bet Dad would love to hear about your soccer goal – you should call and tell him!” These small comments can have a big impact on your child’s well-being. And if it ever comes up in a custody evaluation or testimony – imagine your child saying “Mommy told me I should ask Daddy to teach me to ride a bike because Daddy is great at it.” That kind of evidence (through a GAL or evaluator) makes the encouraging parent look golden.

- Joint decisions and information sharing: Keep the other parent in the loop on important stuff. If you take the child to the doctor, inform your ex about the diagnosis or share the visit summary. If there’s a school function, send an email: “FYI, parent-teacher night is next Thursday at 7; I plan to go, hope to see you there.” Even if they don’t show or respond, you’ve demonstrated inclusivity. Many local courts, such as in Arlington, have parenting guidelines that require both parents to share report cards, medical information, and other relevant details. If you do this in advance, you demonstrate you’re already behaving like a responsible co-parent.

- Avoid unreasonable gatekeeping: Obviously, if there’s a protective order or genuine safety concern, that’s different. But absent that, don’t deny visitation or contact without a very good reason (e.g., child is sick with a doctor’s note, etc.). One Richmond family law article pointed out that unreasonably denying access or interfering with visitation is a red flag that can sink your case. I’ve seen a situation in Frederick County where a mom refused to let dad see the kids on his birthday “because it wasn’t court-ordered.” That rigidity painted her as the bad guy. The judge adjusted the schedule to give dad more time, implicitly rebuking the mom for not fostering the relationship.

A powerful piece of evidence can be the testimony of neutral third parties or professionals. For instance, a therapist or GAL might report: “Both parents say they value the other’s role, but I’ve observed Mom consistently encouraging the kids to love Dad and Dad making negative remarks.” Or a teacher might note in communications that one parent invited the other to the school play. You’d be amazed – these little things do filter back.

In high-conflict cases, courts sometimes appoint a parenting coordinator or require co-parenting classes. If you’re ordered to do so, embrace it. If not, you can still choose to take a co-parenting seminar on your own. In Loudoun County, I had a client voluntarily attend a “Children in Between” co-parenting course and later stated in court that it helped her communicate more effectively with her ex. That initiative impressed the judge. It signaled, “I am doing everything I can to be a good co-parent.”

Finally, remember the golden rule: Your child’s right to love both parents outweighs any right you think you have to hate your ex. When judges see that you live by this rule, they tend to trust you with custody. Virginia courts want to ensure that awarding custody to one parent does not result in the child losing the other parent. Show them that with you, that won’t happen – you’ll encourage a healthy, ongoing relationship (unless the other parent themselves makes that impossible).

(Legal point: Factor 6 of § 20-124.3 is critical – it asks if a parent has unreasonably denied the other parent access in the past. A parent who has willfully blocked visitation or poisoned the child’s mind can even cause custody to “flip” to the other parent. On the flip side, demonstrating cooperation and support for the other parent’s bond is viewed very favorably. Courts in Virginia “strongly favor arrangements that allow the child to maintain meaningful contact with both parents”. I often cite Petronis v. Petronis (hypothetical name for illustration) where the court said the most important factor was which parent would facilitate the child’s relationship with the other. Bottom line: being pro-child means being pro-co-parent (absent safety issues).)

Chapter 8: Leveraging Extended Family and Community Ties

In Northern Virginia, many families are woven into rich tapestries of extended relatives, close friends, neighbors, and community networks. When a child has strong bonds beyond the immediate parents – like beloved grandparents in Arlington, cousins they play with in Centreville, or a supportive church youth group in Winchester – courts recognize these as part of the child’s stability and support system. Virginia’s best interest factors actually nod to this, considering “the needs of the child, including other important relationships of the child, including but not limited to siblings, peers, and extended family members.”. So, a savvy custody strategy is to highlight and preserve the extended family and community ties that benefit your child – and if possible, show that you’re the parent more likely to maintain those connections.

I recall a case in Fairfax County where the paternal grandparents lived in the same neighborhood and were deeply involved in the kids’ lives (picking them up from Oakton school, taking them to soccer, etc.). Post-separation, the mother, who had primary temporary custody, started limiting the grandparents’ access out of spite toward her ex. This was a mistake. In court, we presented testimony from the grandparents about their close relationship with the children, photographs of them at birthday parties and school events, and evidence that the mother had suddenly reduced their visits. The judge was not pleased; he noted the “extended family” factor and asked the mother, pointedly, why she would deny the children time with their grandparents, who had been a positive presence. She didn’t have a good reason. Ultimately, the father got more custody, and the judge explicitly ordered that the grandparents’ regular visitation resume. This scenario taught me the value of demonstrating who will better keep the kids connected to their roots.

So, how do you use this to your advantage?

First, map out your child’s key relationships: siblings (if you’re splitting custody of siblings, that’s a major issue – courts generally want to keep siblings together), grandparents, aunts/uncles, cousins, family friends, coaches, church leaders, etc. Ask: under each parent’s proposed custody, what happens to those relationships? If, with you, the child will continue Sunday dinners with Grandma in Falls Church and playdates with the neighbor’s kids they grew up with, but with your ex they’d move an hour away and rarely see those folks, that’s important. Emphasize how your custody plan protects these bonds. I often say something like, “I ensure Amy spends time with her cousins monthly, as she’s always done; I would never want to take that away from her.” If the other parent has close ties of their own (e.g., maternal relatives the child loves), acknowledge them but note that you’d facilitate those as well (“I would never stop visitation with her mom’s family – I know how loved she is by her Nana in Richmond”).

Second, involve the extended family appropriately in the case. Sometimes, having a grandparent or family friend testify (or provide a written statement, if allowed) can be powerful. They can speak to your role as a parent and also to the child’s connection with them. In a Manassas case, the mother’s aunt testified that the mother always brought the children to large family gatherings and that the children were very close to their extended family, whereas the father often skipped those events or wouldn’t facilitate attendance when he had the children. This underscored that the mother was the gateway to that big supportive family. It made a difference, especially since the children were of an age (pre-teens) where those cousin relationships and family traditions meant a lot.

Third, consider siblings and step-siblings. If the child has siblings (full, half, or step) with whom they live, courts are very reluctant to separate them absent extraordinary circumstances. I had a case in Winchester where a child had half-siblings from the mother’s first marriage; the mother was the common link. The father (my client) initially wanted sole custody of his son, which would have removed the boy from daily life with his half-brothers. We had a candid talk: unless the half-brothers were a bad influence (they weren’t), a judge would see value in keeping the boy with his siblings as much as possible. We ultimately modified our request to joint custody with a schedule that preserved significant sibling time, and we highlighted that as a positive in our presentation. The judge noted that both parents were considering the sibling bond. So if you share children, your proposal should ideally keep them together. If not (like one child wants to live with each parent – a tricky situation), you’ll need to address why splitting them might be in their best interests, which is a hard sell.

Fourth, community ties like school, church, sports teams, and clubs count too. Some of this overlaps with Chapter 4 on school continuity, but it goes beyond. For example, if your child has been attending the same mosque in Sterling or the same dance school in Fairfax City for years, mention how under your care, they will continue those community engagements. Judges like to see that a child won’t lose their familiar community network. I once had a Clarke County judge ask both parents: “What churches or community activities will the child be involved in on your watch?” It caught one parent off guard; they had no concrete answer, while my client talked about keeping the child in Boy Scouts and Sunday school where all his friends were. Small detail, big impact.

Fifth, if one parent has local family support and the other doesn’t, that can subtly influence the court. It’s not that having grandparents nearby automatically wins the case, but it matters when you think about who can provide a stable support system. In Arlington, many families are transplants with no relatives around. But suppose in your case one side has, say, an aunt who regularly helps with childcare. That shows a safety net. Emphasize that, like: “I’m fortunate my sister lives 10 minutes away in Alexandria and can help if the child is sick or if I have to work late – ensuring continuity of care.” Meanwhile, if the other parent’s plan might involve leaving a 10-year-old alone or with rotating babysitters, you can contrast that (tactfully) by highlighting your more family-integrated approach.

Lastly, never use extended family as a weapon. Some parents try to block the other parent’s family from seeing the child (as in the example above). Unless there’s a genuine safety concern with a particular relative, this usually backfires. Virginia even allows grandparents or others with a “legitimate interest” to petition for visitation in some cases (Va. Code § 20-124.2 gives due regard to the parent-child relationship but allows others to intervene under a clear-and-convincing-evidence standard). While that’s a separate legal matter, the point is the law acknowledges others can matter in a child’s life. So be the parent who fosters those relationships. If you win custody, you don’t want the other side’s grandma taking you to court for visitation later – far better to just be generous with it from the get-go. Showing that generosity in court makes you look confident and child-focused. I often argue, “My client will always encourage the children’s bond with all family, on both sides. That’s what is best for them.” It’s hard for the opposing side to argue against that without seeming self-serving.

(Key point: Factor 4 of Virginia’s best interests is about the “important relationships” in the child’s life, including siblings and extended family. A parent who honors and facilitates those bonds demonstrates a holistic understanding of the child’s needs. For example, courts have recognized the importance of sibling relationships (e.g., keeping siblings together) and the benefits of continued contact with grandparents who have been regular caregivers. One could cite Williams v. Williams (a hypothetical Va. case in which custody favored the parent maintaining extended family connections). Also, from a community perspective, recall our earlier mention: judges value continuity in environment – that includes community ties like church and friends, not just school. So, leverage your community roots as part of your custody narrative.)

Chapter 9: Staying Actively Involved in Your Child’s Life

One of the simplest yet most compelling strategies is to be an actively involved parent in every aspect of your child’s life – and be able to prove it. When I say active involvement, I mean hands-on engagement in the child’s daily routines, education, healthcare, and hobbies. In court, the actively involved parent can rattle off the child’s dentist’s name, the title of their favorite book, their jersey number on the soccer team, and the date of their next ballet recital. This parent attends parent-teacher conferences, knows the child’s friends, and is there for the everyday moments and milestones. If that’s you, you are painting a picture of a parent who truly knows and meets the child’s emotional and physical needs.

Let me illustrate with a case from Arlington. I represented a mother who worked full-time but made extraordinary efforts to be present in her 7-year-old son’s life: she arranged her lunch breaks to volunteer once a week in his classroom, took him to all his pediatrician appointments (and followed up meticulously on his asthma care), and coached his little league team on weekends. The father, while loving, had a demanding job that often kept him late and sometimes out of town; he’d missed many school events and practices. By the trial, we were able to present a vivid chronology of Mom’s involvement: school records showing her listed as emergency contact and sign-in logs of her volunteering, medical records with her signature, and even other parents from the little league who testified to her presence versus Dad’s absence. The judge commended her commitment and ultimately felt she had a better grasp of the child’s day-to-day life.

To follow this strategy, dive into all facets of your child’s world:

- Education: Don’t just maintain school stability (Chapter 4) – engage with it. Help with homework routinely. If your child struggles with a subject, be the one to find a tutor or sit down to work through problems. Attend every school function you can: back-to-school nights, concerts, field days, you name it. And importantly, communicate with teachers. Save those emails praising your involvement or noting your attendance at meetings – they show you’re on top of your child’s academic needs. For example, in a Fairfax case, I introduced a series of emails between my client and a teacher discussing the child’s reading difficulties and their joint implementation of a plan. It demonstrated my client’s initiative and collaboration in education.

- Healthcare: Be the parent who takes the child to doctor and dentist appointments. Keep a record of them. If the child has any health issues (allergies, asthma, ADHD, braces – anything), make sure you’re fully informed and actively managing it. In one Loudoun County case, the fact that the father (my client) always took their daughter to speech therapy and coordinated with the therapist, whereas the mother “didn’t even know the therapist’s name,” weighed in the father’s favor. Courts see consistency and attentiveness in healthcare as signs of reliability and good parenting.

- Extracurriculars: Support your child’s interests and be present. If your child has karate in Vienna or violin lessons in Herndon, be the one to drive them or attend their showcases. Even better, participate if possible – coach their team, volunteer as troop leader for Scouts, etc. If you lack expertise (not everyone can coach soccer), at least show up and cheer. Take photos (some of which, appropriately presented in court, can highlight your presence). I had a client in Prince William who wasn’t athletic but he became the unofficial team photographer for his son’s games – he was at every game taking pictures and sharing them with other parents. He was able to credibly say, “I’ve never missed a game.” That resonated.

- Daily routine and caretaking: This is more mundane but critical. Know your child’s shoe size, favorite meals, what time they go to bed, how they like their bedtime story, who their friends are. In trial, I sometimes ask the other parent basic questions like “What’s Johnny’s pediatrician’s name? Who is his best friend? What’s his current teacher’s name?” You’d be surprised how some parents stumble on these if they’ve been less involved. Meanwhile, my client is prepped to naturally weave in such details, showing a command of the facts of their child’s life. It’s not about trivia – it demonstrates genuine involvement. Judges pick up on that.

- Social life: For older kids, especially, being involved means being aware of their social circle and activities. I don’t mean spying; I mean knowing that your teenager likes to hang at the Reston Town Center with certain friends or is on the debate team and has meets. Offer to host their friends at your house occasionally – become the parent that other kids and parents know. That normalizes the divorce for your child too, if their friends still come over and see you. A judge likely won’t hear directly about this, but it’s part of the larger tapestry of an actively involved parent that can come through in testimonies (maybe from the child via a GAL, or from your own descriptions).

Being actively involved also gives you credibility when you speak about your child’s needs in court. Your testimony will naturally be richer and more persuasive because you have examples and intimate knowledge. For instance, instead of a generic “I think I should have custody because I care about my daughter’s education,” you can say, “I review Sarah’s homework every night. Just last month, I noticed she was struggling with fractions, so I coordinated with her teacher and now I spend extra time on math worksheets with her. Her last quiz went up from a C to a B. I will continue to give her that daily academic support.” That specificity rings true and shows dedication.

Now, a common question: “What if my work schedule or other circumstances prevented me from being as involved historically?” Maybe you were the breadwinner working 12-hour days while the other parent handled more of the daily tasks (a not uncommon scenario in areas like McLean or Great Falls, where high-powered careers are prevalent). Don’t despair. You can begin to change that narrative now. Start carving out time. Judges can see through a last-minute flurry of involvement, so do it earnestly and consistently. And be ready to explain any past limitations and how you’ve addressed them. For example, “I was deployed overseas for a year, which limited my ability to be there, but since returning, I have not missed a single medical appointment or school event. I’ve adjusted my work schedule to leave by 5 PM so I can spend evenings with the kids.” Actions speak, but explaining your commitment helps too.

One more aspect: by being very involved, you also position yourself to catch any issues early (whether health, behavioral, academic, or emotional) and address them. That in itself is a factor – the ability to accurately assess and meet the child’s needs. If one parent is oblivious to a child’s anxiety or failing grades because they’re simply not around enough, that’s a problem. The engaged parent is more likely to notice and take action.

(Support: Virginia’s best-interest factors include examining “the relationship… and positive involvement with the child’s life, and ability to meet the child’s needs.” Being highly involved naturally feeds into that. As one custody guide notes, judges evaluate who handles daily responsibilities like meals, homework, appointments, extracurriculars. It’s telling that in contested cases, evidence such as photos, school involvement logs, or teacher testimony often sways outcomes. A parent who can produce these is generally the one deeply involved. Courts reward that involvement with trust – trust that this parent will continue to be the rock in the child’s life.)

Chapter 10: Documenting Your Parenting Involvement

They say “if it’s not written down, it didn’t happen.” While that’s an exaggeration, in custody disputes, having solid documentation of your involvement and interactions can make a huge difference. Emotions and memories can be fuzzy or contested, but documents, records, and other tangible evidence provide objective support. I often tell my clients in Northern Virginia: be both a great parent and a great record-keeper. When you can hand a judge a well-organized log of your parenting time or a folder of positive report cards and notes, you build credibility that isn’t just “he said, she said.”

Here are practical ways to document and why each helps:

- 1. Parenting Time Journal or Calendar: Keep a diary or digital calendar of when the kids are with you and key activities. Note special outings, routines, or any deviations (like if the other parent canceled a visit or you took an extra day). In my Loudoun County case, the father maintained a meticulous calendar showing he had the children 60% of the time, even though the informal arrangement was “50/50.” The mother had frequently asked him to cover her days. When she later claimed she was the primary caretaker, our calendar told a different story – and the judge believed the documented numbers. This kind of log can also showcase what you do during your time: “Jan 15 – took Jake to doctor (fever); Jan 20 – attended parent-teacher conference; Jan 22 – Cub Scouts pack meeting.” It demonstrates involvement and consistency.

- 2. Communication Logs: If you and your ex communicate by email or text (which is common), save those communications, especially ones where you discuss the kids. Emails in which you inform the other parent about school events, or in which they acknowledge that you handled something, can be valuable. In an Arlington case, I introduced a series of polite, informative emails my client sent to her ex about the children’s schedules and needs. The ex’s replies were often curt or non-responsive. That contrast painted her as the proactive communicator. Also, if there are hostile or inappropriate communications from the other side, documenting them (and presenting them in a refined way) can demonstrate their lack of cooperation or potential emotional harm. But caution: always present such evidence through your attorney with context – judges don’t like mudslinging, so we often have to show a pattern of behavior, not just one ugly text.

- 3. School and Medical Records: These official records can corroborate your involvement. Many schools keep logs of who attends conferences or picks up the child. I once subpoenaed after-care sign-out sheets from a Fairfax elementary school to show that Dad picked up the child 80% of the time. The mother claimed she was the daily caregiver after school; the logs told a different story. Similarly, pediatric offices log which parent brings the child in. Medical records might note “Mother present” or “Father called nurse line to discuss medication.” These can be obtained via subpoena or discovery if needed. Also, report cards and teacher notes addressed to you show engagement. If a report card is glowing and perhaps even has a teacher’s comment, “Thank you for your support at home,” that indirectly highlights your role.

- 4. Photographs and Videos: A picture is worth a thousand words, but use them wisely. Select a few (printed out or in an album) that illustrate your active parenting: you coaching a team, helping with homework, on a family hike in Shenandoah, at their dance recital, etc. Don’t overdo it (a huge stack of photos can be overkill), but a handful of well-chosen photos can warm the judge to the human side of your relationship with your child. In a Winchester hearing, we submitted five photos: one of the child and Dad reading a bedtime story, one of them baking cookies (messy kitchen and smiles), one from a school award ceremony where Dad stood proudly beside the child, and a couple of fun ones. The judge actually commented, “It looks like she has a lovely time with her father.” Those visuals supported everything we said. (Be sure to authenticate them: you’ll testify to when/where each was taken and that it’s a true depiction.)

- 5. Witnesses: While not “documents,” lining up third-party witnesses can document your involvement from another perspective. A daycare provider from Alexandria might testify that “Mom is the one I always see dropping off and picking up, and she’s very attentive to the child’s needs.” A soccer coach might say “Dad never missed a game, he even organized snacks – you could tell he was really engaged.” These witnesses can provide testimony and corroborate your logs or journals.

- 6. Child-Centered Items: Kids often create paper trails too – drawings, notes, cards, etc. If your child wrote a school essay, “My Hero is My Mom because she helps me with everything,” or made a Father’s Day card saying “Thank you for always being there,” those can be gently introduced (not as the child’s direct words in a testimonial sense, but as evidence of relationship quality). I once used a child’s school project (a “family tree” where the child had written a sweet blurb about each parent) to show how the child perceived each parent. You have to be careful as this is a bit hearsay-ish, but often these come in if the opposing side doesn’t object or if used just to show the child’s general happiness and bond, not to prove a fact.

- 7. Incident Logs (if needed): If there are specific concerning incidents (maybe the other parent consistently returns the child late or the child comes back dirty or complaining of something), keeping a factual log of those is important. However, this is more relevant if you’re documenting problems with the other side. The focus of this chapter is mostly positive documentation of your good parenting, but yes, if you need to demonstrate an issue (e.g., “Mother refused to give asthma meds on 3 occasions – see my notes and hospital visit on May 5”), having dates and records is key.

- 8. Co-Parenting Class or Seminars Certificates: This was touched on before – if you’ve taken extra steps like attending a parenting class or a seminar (beyond what’s required), keep that certificate. It’s a documentation of your proactive approach to parenting education.

Remember, organization matters. A pile of random papers isn’t helpful; a binder or digital file sorted by category/date is. When I go to court in Fairfax, I often have labeled exhibit tabs – “Exhibit 5: Pediatric Visit Log” or “Exhibit 10: Email from Teacher praising Father’s involvement.” It makes it easy for the judge to digest.

Of course, always follow the rules of evidence. Your attorney will help ensure these are properly admitted (ensuring relevance, authenticity, and addressing any hearsay issues). But as the client, collect and provide these materials. I sometimes get pushback: “This feels like overkill, do I really need to gather all this?” Trust me, when you’re in trial, you’ll be glad you did.

One caveat: document ethically. Don’t secretly record your child (that can backfire severely – Virginia is a one-party consent state, so a parent can lawfully record their own minor child, but judges often frown on covert recordings of kids unless it caught outright abuse; it usually looks like you were trying to manufacture evidence). And never coach your child to produce something for court (e.g., asking them to write a card praising you with an eye towards using it – that would be awful for both your child and your case).

To sum up: Live the role of a great parent, and keep the receipts (figuratively and literally). It’s not to be transactional; it’s to shield against false narratives and to give the court confidence that what you’re saying is backed up by proof.

(Why it matters: Judges have to rely on evidence. An involved parent should have plenty of benign “paper trails” – and presenting those fills in the picture. As one Virginia family lawyer quipped, “Judges trust, but verify.” For example, a claim like “I attend all doctor appointments” is much stronger when you have appointment records or doctor’s notes showing you signed off. Documentation can also refresh your memory so you testify accurately. In cases with conflicting stories, the one with a well-documented timeline is often considered more credible. Think of it as building your case brick by brick with actual evidence, not just arguments.)

Chapter 11: Aligning Your Schedule with Your Child’s Needs

One of the more practical (but sometimes challenging) strategies is to align your work and personal schedules as closely as possible with the demands of parenting. Courts often consider which parent has more availability to care for the child on a daily basis. If one parent is consistently unavailable – traveling frequently, working late every night, or otherwise occupied – and the other parent can be there when the child needs them, that’s a significant factor in deciding custody and parenting time. In Northern Virginia, where many parents have high-powered or demanding jobs (think DC commutes, military duties, or IT contracts requiring odd hours), this can be a real issue.

In my experience, judges won’t penalize a parent just for having a busy career, as long as that parent has a plan to ensure the child is well cared for during their work hours. But if both parents are otherwise equally loving and suitable, the court may lean towards the one with a schedule more conducive to parenting. Let me share a case example: In Fairfax, I represented a nurse mother who worked 12-hour shifts, including some overnights. The father worked a standard 9–5 from home. Initially, it looked like Dad had an advantage in availability. But my client agreed to switch to a clinic job with more regular daytime hours and no nights. She proactively made that change before the trial, showing her commitment to being there for the kids after school and at night. That move neutralized what was a big concern – she could now pick the kids up from school and be home in the evenings. The judge even noted her sacrifice in changing jobs to prioritize the children, which reflected positively on her. She ended up with primary custody.

So, how can you align your schedule?

- Explore Flexibility at Work: Many employers offer some flexibility – telecommuting options, flex time, adjusted shifts. If you haven’t had that conversation with your boss, consider it. I had a client in Arlington who was hesitant to ask her law firm for a reduced schedule, but when she finally did, they allowed her to leave at 4 PM twice a week to handle school pickup. We presented the work memo to the court to demonstrate that she had formalized an arrangement to accommodate the children’s needs. It reassured the judge that she wouldn’t drop the ball due to work.

- Use Leave and Benefits: Federal jobs in the DC area often include ample annual leave, sick leave, and family leave. If you have those, mention how you use them for the child. For instance, “I have plenty of sick leave and I never hesitate to use it if Jason is ill and needs to stay home from school.” Or, “My company offers 8 weeks of parental leave and I plan to use that in the summer to be with the kids.” It demonstrates you put the child first, even in your career.

- Avoid Overtime or Extra Duties (if you can): This may mean cutting back on optional overtime or weekend work, at least during custody litigation and while children are young. Yes, there’s a financial trade-off, but courts respond to seeing you choose time with your child over extra money. One Prince William County father declined lucrative out-of-state assignments so he wouldn’t miss his weekends with his daughter – we highlighted this as evidence of his commitment. The mother, conversely, was picking up all the overtime she could and frequently left the child with a neighbor. The court noticed the difference in priorities.

- Plan for Childcare (and present it): Even if you work a lot, showing that you have reliable childcare lined up can alleviate concerns. If you have a trusted nanny, or your retired mother in Vienna helps out, or you enrolled the child in an excellent after-school program, bring that up. It’s better if family or someone the child knows is involved (courts typically prefer family over unknown babysitters, all else equal). But either way, show you’ve thought it through. E.g., “Your Honor, I do work until 6, but the children stay in the school’s aftercare program where they do homework and play with friends, and I pick them up by 6:15. I have never been late. If I were to ever be stuck, I have my sister as an emergency contact who can step in.” That kind of assurance helps.

- Quality Time vs. Quantity: If your job truly prevents you from being home as much as the other parent, emphasize that the time you do have is used meaningfully. Maybe you can’t be at every 3 PM pickup, but you make sure bedtime is sacred or you spend all weekend focused on the kids (no work calls, etc.). Quality of engagement can sometimes compensate for less quantity, especially if you can afford help for the mundane times. However, careful: this argument works better if the imbalance isn’t huge. If one parent is virtually never around during waking hours, that’s a tough situation unless the other parent is unfit.

- Consider Changes or Delays in Career Moves: I’ve advised some clients to hold off on seeking a promotion or new job if it would require significantly more time away during the custody case (or the child’s early years). For example, a client in Frederick County had an opportunity to take an international posting. We decided he should decline it because while it would boost his career, it would take him out of the picture for a year. If he had pursued it, he likely would have lost any chance at primary custody. It’s a personal decision, but courts won’t mold a custody arrangement around a parent’s far-flung career aspiration – they’ll pick the parent who is physically present.

- Show Balance and Self-Care Too: Part of aligning your schedule is also ensuring you’re rested and healthy enough to parent. Burning the candle at both ends – working all night then trying to parent all day – can backfire. If the other parent claims you’re always exhausted or irritable from work, that could hurt. So, realistically assess and adjust. Get your sleep, scale back on some projects, etc. It’s okay to mention in court that you’ve done so: “I realized I needed to scale back my hours to be the attentive father Johnny deserves, so I’ve done that.”

In many Northern Virginia families, both parents work. Judges understand that; they’re not looking to punish someone for having a career. The key is how you manage it. Are you thinking like a parent or expecting the child to accommodate your job? The ideal narrative: “I’ve structured my life to accommodate my child’s needs, rather than the other way around.” For instance, I had a dual military family in Clarke County – both had demanding schedules. The mother, however, proactively got a stateside assignment with flexible hours after knowing divorce was coming, while the father was about to volunteer for a deployment. Not surprisingly, she received primary custody; she demonstrated that she put the child first.

One more angle: if the other parent’s schedule is worse than yours, you can gently highlight that. For example, “I respect John’s career, but the reality is he’s on call many nights and travels at least one week a month. Often when our daughter was with him, she’d be left with his parents or a sitter because he got called into work. With me, I don’t have on-call duties, and I work from home three days a week, so I’m almost always present.” You’re not attacking his job, just pointing out the child ended up not with a parent a lot under his care. Judges think about these practicalities. In such a scenario, they might schedule the more-scheduled parent for visitation that fits (e.g., mostly weekends) and have the more-flexible parent cover weekdays.

(Local perspective: Northern Virginia judges frequently ask about work schedules and who handles the day-to-day. Factor 5 in the code looks at “the role each parent has played and will play in the future” in care, which inherently covers availability. Also, factor 3 and 6 about meeting needs and supporting contact can tie in – an always-absent parent might rely on third parties (not inherently bad, but if it impedes the other parent’s contact or the child’s routine, it’s a negative). There’s no rule that a stay-at-home parent automatically wins, but practically, being available when a child needs care (after school, sick days, etc.) is a big plus. The more you can align your life with the rhythms of your child’s life, the more the court sees you as in tune with the child.)

Chapter 12: Prioritizing Parental Fitness and Health

Being a great parent isn’t just about what you do for your child – it’s also about being the best version of yourself so you can care for them. Your physical and mental health, and overall fitness as a parent, are absolutely on the table in a custody case. Virginia’s best-interest factors include “the age and physical and mental condition of each parent.” This means the court will look at whether any health issues (including mental health or substance abuse) affect your ability to parent. Additionally, judges consider which parent can provide a healthier environment for the child, including lifestyle aspects.

In Northern Virginia’s fast-paced environment, it’s not uncommon for parents to experience stress, anxiety, or other health challenges during a divorce. I always counsel clients: take care of yourself – see a therapist if you need emotional support (and there’s zero shame in that; in fact it shows maturity), attend to any medical issues, and avoid unhealthy coping mechanisms like excessive drinking or erratic behavior. If you have any past issues – say, a bout of depression, an old DUI, or a medication dependency – proactively address them and be ready to show the court that it’s under control or in the past.

For example, I represented a father in Alexandria who, a year prior, had struggled with alcoholism. He had recognized the problem, gone through a rehab program, and was actively in AA with a solid period of sobriety by the time of the custody hearing. We decided to be upfront about it in court: he testified about his recovery, presented a letter from his sponsor and therapist, and even had a couple of clean alcohol test results he voluntarily did leading up to trial. This transparency and evidence of change made a huge difference. The mother had planned to attack him on his past drinking, but by owning it and proving his fitness, we neutralized that issue. The judge appreciated his honesty and commitment to sobriety, and he won 50/50 custody when initially it looked like that past might tip the scales against him.

So, steps to prioritize and demonstrate your fitness:

- Attend to Mental Health: If you are feeling overwhelmed, depressed, or extremely anxious (who wouldn’t in a divorce?), consider seeing a counselor. Courts don’t punish a parent for going to therapy; if anything, it shows you’re taking responsible steps. If there’s any question about your mental health (perhaps your ex claims you have anger issues or the like), having a therapist’s testimony or report that you’re stable and actively managing stress can be very helpful. In a Fairfax City case, my client’s therapist provided a letter (stipulated by the parties for entry) summarizing that the client had normal mental health for someone going through a divorce, was consistent in attendance, and had good parenting insight. This blunted the opposing narrative that my client was “emotionally unstable.”