Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

Families in Tysons Corner, Virginia, an affluent community known for its high-net-worth households, often face complex legal challenges in divorce and custody matters. Virginia’s family laws provide a framework for equitably dividing substantial assets, determining child custody under the “best interests” standard, setting fair support obligations, and encouraging mediation to reduce conflict. This guide offers an in-depth look at high-net-worth divorces, child custody, support disputes, and mediation in Virginia, with empathy for the human side of these issues and references to recent 2023–2025 Virginia laws and cases for context.

This article is designed as an authoritative yet compassionate legal resource for high-net-worth families in Tysons Corner, navigating divorce, custody, support, and mediation. It addresses equitable distribution of complex assets custody decisions under the best interests standard, evolving child support laws, and mediation as a practical path forward under Virginia law.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: The High Stakes of High Net Worth Divorce

Scenario: Imagine a Tysons Corner couple, both successful professionals, deciding to end their marriage. Between them, they have a family business, multiple properties, and substantial investments. Both spouses worry: who will get what, and will it be fair? This scenario is common in high-net-worth divorces. Emotions run high, and the stakes – both financial and personal – are enormous.

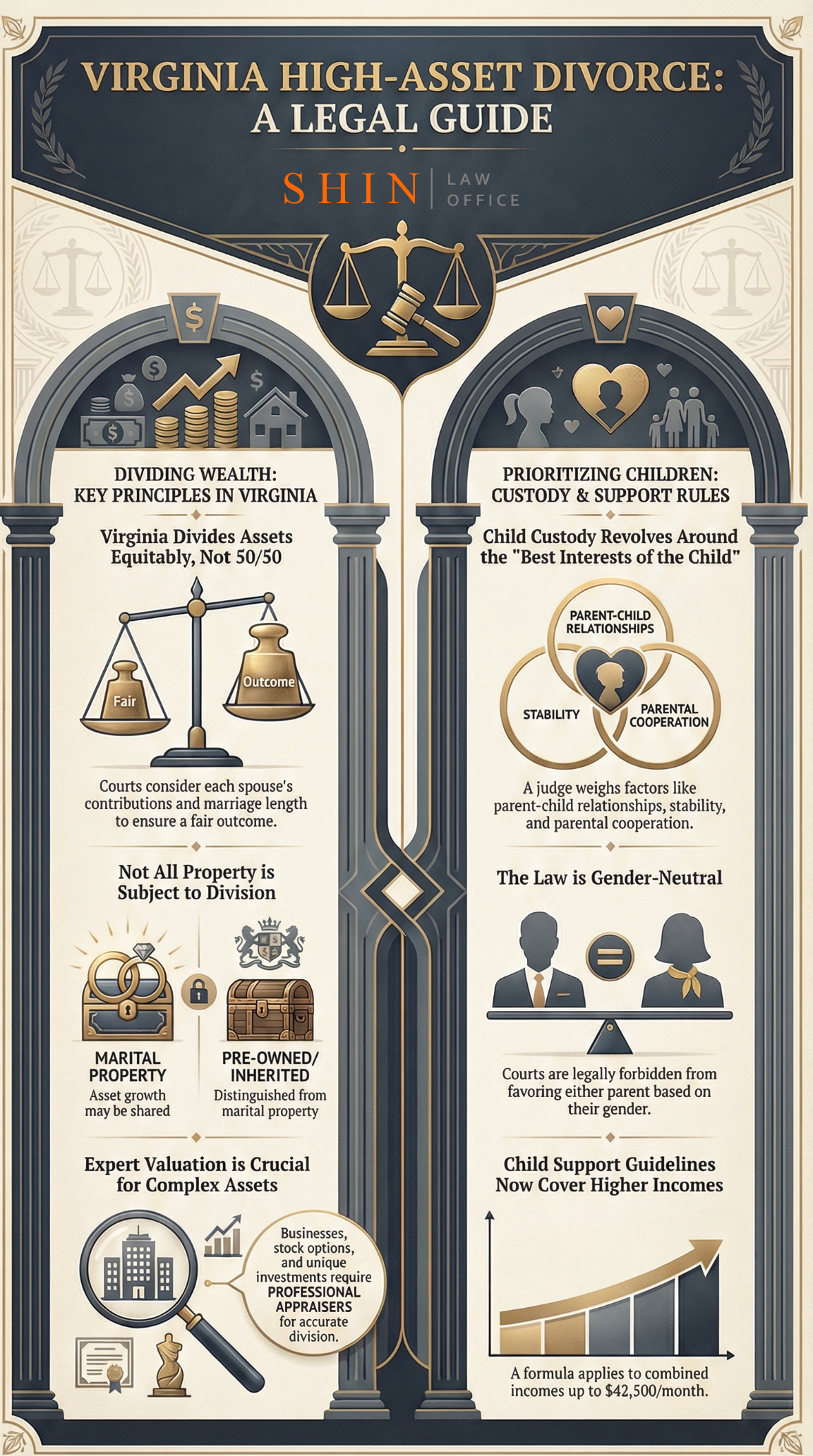

Equitable Distribution (Not 50/50): Virginia is an equitable distribution state, meaning marital assets are divided fairly rather than equally. Unlike in some states where a 50/50 split is the rule, Virginia courts consider a range of factors to decide what is fair, such as how and when assets were acquired, each spouse’s contributions (including non-financial contributions like homemaking), the length of the marriage, and even the tax implications of property division. In other words, just because an asset is in one spouse’s name doesn’t mean the other spouse has no claim, and a higher-earning spouse isn’t automatically entitled to a greater share. The goal is a result that is determined solely by the couple’s unique circumstances.

Marital vs. Separate Property: A critical step is determining what property is marital, separate, or hybrid. Marital property includes assets acquired during the marriage (income, homes, etc., except certain gifts or inheritances), and it’s subject to division. Separate property includes assets one owned before marriage or received individually as a gift or inheritance, and it generally remains that person’s property. Virginia law also recognizes “hybrid” property – assets that are part marital and part separate. For example, a house bought by one spouse before marriage could become a hybrid if marital funds (like joint earnings) were used to pay the mortgage or improve the home. In high net worth situations, this distinction can become a major battleground: Did one spouse’s premarital trust fund contribute to a joint investment account? Did an inheritance get commingled into the couple’s finances? These questions can significantly affect “who gets what,” and Virginia courts will examine the source of funds and any increases in value during the marriage.

Increases in Asset Value: Even separate property can have a marital component if it grows in value during the marriage due to marital contributions or efforts. Under Virginia law, if an asset like a business or real estate owned by one spouse before marriage increases in value thanks to the personal efforts of either spouse or the use of marital funds, that increase can be classified as marital property. For instance, if a spouse’s separate investment portfolio grew because the other spouse actively managed it, or if the value of a premarital home rose partly because marital earnings paid the mortgage, a portion of that growth may belong to the marital estate. Virginia’s statute explicitly says that an increase in separate property is marital property “only to the extent” that marital funds or a spouse’s significant personal effort caused the increase. The non-owning spouse must show a link between marital contributions and the increase; then the burden shifts to the owning spouse to prove that the growth was due to other factors (like market forces) rather than the marriage. In a 2023 case, Spaid v. Spaid, the Virginia Court of Appeals applied these rules to a family home, ultimately ruling that the increase in the home’s equity during the marriage was marital because it resulted from mortgage payments made with marital income and normal appreciation. The husband’s argument that the value rose “due to the economy” alone was rejected – he had to share that gain with his ex-wife in proportion to the marital investment in the property.

Valuing Complex Assets: High-net-worth divorces often involve assets far more complex than a house or a checking account. Couples may have business interests, stock portfolios, retirement accounts, investment properties, stock options, or even luxury items like art collections, yachts, or expensive jewelry. Accurately valuing these assets is a crucial, sometimes contentious, part of the process. Virginia courts will not simply “guess” at values – they rely on expert appraisers and forensic accountants to provide valuations. For example, if the couple owns a company, an expert may be brought in to assess the company’s revenue, profits, and future earning potential, and to determine how much of the business’s success is attributable to each spouse. In Northern Virginia (including Tysons Corner), it’s not uncommon to see teams of financial experts in a high-asset divorce, given the prevalence of family businesses and complex investment vehicles in this area.

Hidden Assets and Transparency: With large sums of money on the line, some spouses, unfortunately, try to hide assets or understate their value. This might involve underreporting income, shifting money to relatives or offshore accounts, or using complex methods such as cryptocurrencies to conceal wealth. Virginia courts take a very dim view of dishonesty in financial disclosures. If one spouse suspects the other is not being truthful, the court can compel extensive discovery of financial records, and forensic accountants can be hired to trace funds and uncover any “missing” money. Importantly, if a spouse is caught hiding assets or lying about finances, the judge has discretion to award a greater portion of the marital assets to the other spouse as a penalty for the deception. In other words, attempting to cheat can backfire badly. For anyone in a high net worth divorce, the best practice is to start gathering detailed financial documentation early – tax returns, bank statements, business records – to ensure all assets are accounted for. Virginia law’s emphasis on evidence means that well-documented claims (for example, proof that marital funds were used to increase an asset’s value) can significantly affect the outcome.

Spousal Support in High Asset Cases: Another major aspect of high net worth divorces is spousal support (alimony) – though we’ll discuss this in depth in Chapter 3, it’s worth noting here. In long marriages in which one spouse was the primary earner, and the other perhaps left a career to support the family, Virginia courts may award substantial, and even indefinite, spousal support. The standard of living established during the marriage is a key factor; a wealthy lifestyle during the marriage could lead to a correspondingly significant support award to the less wealthy spouse. High asset divorces often result in intense negotiation (or litigation) over alimony, because the amounts can be large and the duration long-term. Additionally, recent changes in tax law have removed the tax deduction for alimony payments (and the inclusion of alimony as taxable income for the recipient). Since 2019, payers can no longer deduct alimony, and recipients don’t pay tax on it – a change that has led to more strategic negotiations over the amount, as the tax advantage of paying alimony was eliminated. This is something high-net-worth individuals and their lawyers now factor into their support decisions.

Empathy and Professional Guidance: Going through a high-net-worth divorce in Tysons Corner can feel overwhelming. On top of the emotional toll of a marriage ending, there’s a maze of legal and financial issues to navigate. It’s important for spouses to surround themselves with a solid support team – experienced family law attorneys, and when needed, financial experts – who understand Virginia’s laws and the local Fairfax County court practices. While the process can be contentious, remember that the law is ultimately designed to reach a fair division of assets. With full financial transparency and proper guidance, both parties can reach a settlement that allows them to move forward securely. As one Northern Virginia divorce attorney aptly put it, a high net worth divorce “is not just about dividing assets but about securing your financial future”. Keeping that long-term perspective can help spouses focus on pragmatic solutions rather than on revenge or short-term victories.

Chapter 2: Child Custody: Best Interests of the Child

Scenario: Picture a divorcing couple in Tysons with two young children. Both parents are devoted to the kids but have very different ideas about custody. One parent’s job is demanding with long hours, while the other has more flexibility. They worry: how will a court decide who the kids live with, and how can they ensure the children don’t suffer? This is where Virginia’s child custody laws step in, guided by a single paramount concern: the best interests of the child.

Best Interests Standard: In Virginia, every custody and visitation decision revolves around the “best interests of the child” (Va. Code § 20-124.3). This means the judge will prioritize the child’s well-being above all else, setting aside what might be easiest or most convenient for the parents. To determine what arrangement best serves the child’s interests, Virginia law directs courts to consider a broad list of factors, providing a 360-degree view of the child’s life and needs. These factors include, for example:

- The child’s age and developmental needs. A toddler has different needs than a teenager, and the court will consider the child’s age, physical health, and emotional and mental development.

- Each parent’s mental and physical health. If one parent has health issues that might affect their ability to care for a young child (or conversely, if a parent is exceptionally capable and healthy), that matters.

- The relationship between the child and each parent. The court looks at the existing bond – who has been the primary caretaker, how each parent meets the child’s emotional and intellectual needs, and the level of involvement each parent has had in the child’s life. For instance, evidence of who takes the child to doctor’s appointments, helps with homework, or attends extracurricular activities can be influential.

- The role each parent has played and will continue to play. Past involvement is important, but so is the willingness to continue caring for the child. A parent who perhaps worked long hours during the marriage might need to show how they will make time for the child after divorce if they want primary custody.

- The child’s needs and important relationships. This includes not just material needs but emotional needs and relationships with siblings, friends, and extended family. Stability and continuity in schooling and community can be part of this analysis.

- Each parent’s willingness to support the child’s relationship with the other parent. Virginia courts strongly favor parents who foster an ongoing healthy relationship between the child and the other parent. If one parent has been actively undermining or refusing contact (without a good reason such as abuse), the court will weigh that negatively. This factor aims to ensure that a parent won’t attempt to “poison” the child against the other parent or unreasonably block visitation.

- Ability to cooperate. The court will consider how well the parents can communicate and make joint decisions about the child. High conflict between parents can influence arrangements – for example, joint custody (which requires cooperation) may not work if parents absolutely cannot get along. Conversely, parents who show they can set aside personal grievances for the child’s sake will be viewed favorably.

- The child’s preference (if of suitable age and maturity). There is no set age in Virginia at which a child’s preference automatically determines custody, but if the child is old enough and mature enough (often teens), the court can consider their wishes. The judge may speak with the child in chambers or consider testimony on this. However, the child’s preference is just one factor – it won’t control the outcome if the judge believes another arrangement is better for the child.

- History of abuse or violence. If there is any history of family abuse, child abuse, sexual violence, or the like by one parent, that is a critical factor. In fact, Virginia law says a court may disregard the friendly-parent factor (the one about supporting the child’s relationship with the other parent) if evidence shows a history of family abuse by that parent. The safety and well-being of the child come first.

All these factors (and a few others listed in the law, such as “any other factors the court deems necessary”) must be weighed by the judge in making a custody determination. The judge doesn’t give each factor a numeric score or equal weight – some factors may matter more in a particular case – but the court’s final custody order must reflect a consideration of all relevant factors. In fact, Virginia law requires judges to communicate the basis of their decision, either in writing or orally in court, and they typically will reference the key factors that led to their conclusion. For parents, this means that in any custody dispute, they should be prepared to present evidence and examples for each factor: demonstrate their positive involvement, their plan for the child’s care, their willingness to co-parent, etc.

No Automatic Preference for Either Parent: It is a common fear or misconception that courts favor mothers over fathers (or vice versa) in custody cases. In Virginia, the law explicitly forbids any gender-based presumption: “there shall be no presumption or inference of law in favor of either” parent. Mothers are not inherently assumed to be better caretakers, and fathers are not presumed to be less important – the court starts from a position of neutrality between the parents. The only preference is what’s best for the child. Additionally, Virginia courts aim to ensure the child has frequent and continuing contact with both parents when appropriate. In practical terms, this means that, absent issues such as abuse or neglect, the courts encourage shared parenting. Joint custody arrangements (whether legal, physical, or both) are common. Even when one parent is granted primary physical custody, the other parent will usually receive generous visitation because it’s presumed beneficial for children to have both parents actively involved in their lives.

Types of Custody: Virginia distinguishes between legal custody (decision-making authority over important matters such as education, medical care, and religious upbringing) and physical custody (where the child lives day-to-day). The court can award joint legal custody (both parents share major decisions) even if physical custody is primarily with one parent. Courts in Fairfax County, for example, often encourage joint legal custody so that both parents remain part of important decisions, unless there’s a compelling reason one parent should have sole decision-making power (e.g., inability to cooperate or domestic violence issues). Physical custody can be sole (one parent has primary residence and the other has visitation) or joint (the child splits time between homes). There is no one-size-fits-all: a schedule could be week-on/week-off, with one parent having weekends and holidays, or any number of creative arrangements – whatever fits the family’s circumstances and the child’s needs.

Modification of Custody Orders: Life isn’t static – kids grow, parents’ jobs change, people relocate. Virginia acknowledges that custody orders may need to be changed over time. However, once a final custody order is in place, a judge won’t modify it on a whim or just because one parent is unhappy with it. To modify custody or visitation, the requesting parent must show two things: (1) a material change in circumstances since the last order, and (2) that a modification would be in the child’s best interests. A “material change” could be practically anything significant: the child’s needs have changed (for example, a teenager might have different needs or express a preference), or a parent’s situation has changed (remarriage, move to a new location, new job schedule, rehabilitation from a past issue, etc.), or unfortunately something negative like a parent developing a substance problem or a household becoming unsafe. The idea is that courts want stability for children, so they won’t reopen a settled custody arrangement unless there’s been a real shift in the situation. If that threshold is met, the court conducts another best interests analysis to decide which new arrangement best serves the child.

To illustrate, consider a recent Virginia Court of Appeals case in 2024: Garrett v. Hanna. In that case, the father sought to change custody after the child’s mental health took a downturn and he alleged the mother was interfering with his relationship with the child. The court found there was a material change – notably, the child had developed serious emotional issues and the mother’s behavior (not fostering a good relationship with dad) was concerning. The trial court carefully reviewed all the statutory best-interest factors (found in § 20-124.3) and decided it would indeed be best for the child to live primarily with the father. The Court of Appeals upheld that decision, emphasizing that there was credible evidence of both the change in circumstances (the child’s declining mental health and the mother’s obstruction of visitation) and that the father could better meet the child’s needs in light of those developments. This case highlights a few things: Virginia courts will act if a child’s welfare is at stake, they require solid evidence (counselor’s reports, testimony, etc.), and they give a lot of deference to trial judges who weigh the best-interest factors – an appeals court won’t second-guess a custody decision if the trial judge applied the law correctly and had evidence to support it.

Co-Parenting and Parenting Plans: Many parents in Tysons Corner opt to work out a parenting plan either through negotiation or mediation (which we discuss in Chapter 4). A parenting plan is essentially a detailed agreement covering physical custody schedules, holiday rotations, decision-making protocols, travel, and other parenting rules. Virginia courts welcome reasonable agreements – if parents can agree on a plan they believe is best for their child, the court will usually approve it as a court order (as long as it is indeed in the child’s best interests). Having a say in crafting the plan can make both parents more comfortable and lead to a more cooperative co-parenting relationship post-divorce. Even if you can’t agree on everything, narrowing down the issues (say both agree neither will move out of the school district without consent, or both will use a shared calendar app for scheduling) can reduce conflict and show the court that you’re putting your child first.

Local Perspective: Tysons Corner is in Fairfax County, which has a well-respected family court system. Fairfax County judges are experienced with complex family situations common to this area – from international custody issues (with many diplomats and global professionals in the D.C. metro) to high-conflict custody battles. The court may appoint a Guardian ad Litem (GAL) for the child in contentious cases. A GAL is an attorney who represents the child’s interests and provides an independent recommendation to the court. In high net worth cases, sometimes GALs are brought in if the custody fight is particularly acrimonious or if there are allegations that require investigation from the child’s perspective. Additionally, Fairfax County offers coparenting classes and resources that judges might require or suggest for feuding parents to help them communicate better for the sake of the kids.

Bottom Line: In Virginia, the law aims to ensure that children of divorced or separated parents maintain healthy, supportive relationships with both mom and dad, whenever possible. Parents are encouraged to rise above their personal conflicts and focus on what their children need. As one custody statute puts it, the court’s procedures should “preserve the dignity and resources of family members” and encourage parents to share in the responsibilities of rearing their children. For parents in Tysons Corner, understanding the best-interests factors and demonstrating a cooperative, child-first mindset can not only improve their chances of a favorable outcome but also ease the emotional strain on their children during what is often a very difficult time.

Chapter 3: Child and Spousal Support Challenges

Financial matters are a major source of stress for families going through a breakup. In high net worth situations, child support and spousal support obligations can be significant – and disputes often arise over what is fair or necessary. Virginia has guidelines and laws for calculating support, but they have limits and exceptions, especially for higher-income families. In this chapter, we’ll break down how child support is determined (particularly for affluent families in Tysons) and how spousal support (alimony) works, including recent legal developments in Virginia that affect these obligations.

3.1. Child Support in High-Income Cases

How Child Support is Calculated: Virginia, like other states, uses child support guidelines – essentially a formula set by statute – to calculate the presumptive amount of support one parent pays the other for the children’s needs. The guideline takes into account both parents’ gross incomes, the number of children, and certain expenses (such as health insurance or daycare costs), and then allocates an amount to be paid for the children. For the average family, this formula is straightforward. However, for high-income families, the guidelines historically had an upper limit – they topped out at a certain combined monthly income, beyond which the formula didn’t directly apply, and courts had to use discretion. This is very relevant in Tysons Corner, where many families exceed the typical income brackets.

Recently, Virginia updated its child support guidelines for the first time in over a decade. As of July 1, 2025, the guidelines now explicitly cover combined gross monthly incomes up to $42,500. This is an increase from the previous cap of $35,000 per month. What does this mean? It means that many high-earning Northern Virginia families who used to be “off the chart” are now on the chart. For example, a couple with a combined income of $40,000 per month (about $480,000 per year) will now receive a presumptive support number from the guideline table, whereas before the law change, the judge would have had to exercise broad discretion because the old chart capped at $35k. This change brings more predictability – parents making between $35,000 and $42,500 a month combined no longer have to rely solely on a judge’s subjective judgment; the law provides a clearer formula. In communities like Tysons, McLean, or Great Falls, where combined incomes frequently fall in that range or above, this update is significant.

For families above the $42,500/month threshold, the law doesn’t leave you hanging. The new statute provides guidance for extrapolating beyond the cap: essentially, the court will take the maximum guideline amount of $42,500 and add a percentage of income above that figure. The percentage depends on the number of children. For one child, it’s about 2.6% of the income over $42,500; for two children, around 3.4%; and it increases up to a max of 5% for six children. This sliding scale ensures that child support continues to rise with very high incomes, but at a tempered rate so that it’s not purely proportional at extreme levels. The rationale is to avoid a windfall that far exceeds any reasonable needs of a child, while still reflecting that higher earners can and should contribute more to their children’s upbringing. For instance, if a Tysons couple has one child and makes $50,000 a month combined, the guideline would calculate support as the guideline amount for $42,500 (roughly $3,306 for one child) plus 2.6% of the extra $7,500, which is about $195, for a total of ~$3,501 per month. This method scales upward in a controlled way.

Broad Definition of Income: One aspect that can catch people off guard is what counts as “income” for child support. Virginia’s definition of “gross income” for support purposes is very broad – it includes “all income from all sources” (Va. Code § 20-108.2(C)). Obviously, regular wages, salaries, and bonuses count, but it doesn’t stop there. It includes things like commissions, investment income (dividends, interest, capital gains), rental income, pension payouts, Social Security benefits, and more. It even includes one-time or irregular income, such as lottery winnings, prizes, gifts, etc., unless a specific statute excludes it. To illustrate, a 2022 case in Virginia (Williams v. Sykes-Williams) underscored the point when a $52,000 cash gift given to one parent (to help with legal fees) was deemed income for support calculations. More recently, in 2025, the Court of Appeals decided Herbert v. Joubert, which addressed a very modern issue – COVID-era Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans. In that case, both parents had taken out PPP loans for their businesses and later had them forgiven (meaning they didn’t have to pay them back). The question was: Should that forgiven loan money count as income for child support? The Court of Appeals said yes, it should. Once forgiven, those funds were effectively free money the parents could keep, so they were a financial resource available to them just like any other income. The court held that forgiven PPP loans fall squarely within Virginia’s broad income definition and must be included in support calculations – even though they were a one-time windfall tied to a unique situation (the pandemic). In reaching that conclusion, the court noted that Virginia law intentionally casts a wide net for what constitutes income, including even irregular payments such as gifts or prizes unless explicitly excluded.

What these examples mean for high net worth cases is that you have to consider all streams of money. If a parent regularly receives substantial stock options or perhaps a large annual bonus, those are part of the calculation. If a family’s income is mainly from a business they own, the profits of that business (after reasonable business expenses) count as income. One-time events – say one parent sells off valuable stock for a big gain or receives an inheritance – can also be considered in support, though inheritances themselves aren’t “income,” any interest or profit generated from them would be. With high incomes, it’s also common for courts to look at things like perquisites (company-paid cars, housing allowances) as part of the financial picture.

Adjustments and Deviations: The guideline amount is presumed to be the correct amount of child support, but it’s not an absolute rule. Virginia law allows either parent to argue for a deviation – a higher or lower amount than the guideline – if following the guideline would be unjust or inappropriate in a particular case. In high-income cases, a frequent issue is that the guideline number might be far above what is actually needed to cover a child’s reasonable expenses. For example, the basic needs of a child (food, clothing, shelter, education) might be met with a few thousand a month, and if the guideline says, say, $8,000/month, a judge might consider whether that exceeds the child’s needs. The law lists many factors for possible deviations, including: the child’s standard of living during the marriage (if the child lived a very affluent lifestyle, that can justify higher support to maintain it); the financial resources of each parent (if one parent has significantly more disposable income or assets, maybe they can pay more); any special needs of the child (such as medical conditions, learning disabilities requiring special schooling, etc.); and direct payments for the child’s benefit (for instance, if a parent pays tuition for private school or pays for the child’s health insurance or costly extracurricular activities). A court may deviate downward if the guideline would effectively give a “windfall” to the custodial parent that far exceeds the child’s needs. Conversely, it could deviate upward if, say, the child has a lavish lifestyle and extraordinary expenses that the guideline doesn’t fully account for, or if one parent’s wealth is so massive (think ultra-high net worth) that the guideline underestimates what could reasonably be provided for the child. The key is evidence – the parent requesting a deviation should be prepared to show why the guideline amount is not appropriate by detailing the child’s actual expenses or needs and the parents’ financial situations.

Child Support Enforcement and Modification: Once an order is in place, child support must be paid or the parent will face legal consequences (wage garnishment, contempt of court, etc.). Support typically continues until the child turns 18 (or finishes high school if 18 and still in school, up to age 19), although for a severely disabled child, support can continue into adulthood (and parents can voluntarily agree to support beyond 18 for college, though courts can’t mandate college support). If circumstances change – for example, a high-earning parent loses their job or conversely gets a big promotion, or the custody arrangement changes significantly (affecting who pays whom) – either parent can request a modification of child support. As with custody, they’d need to show a material change in circumstances. Notably, the 2025 update to the law itself (the guideline increase to a $42,500 cap) is considered a material change; so if your support order was entered before July 1, 2025, and your combined income was above the old cap, you might be eligible to revisit support under the new formula. This is something worth discussing with a lawyer if you’re in that boat, as it could mean a substantially different obligation now.

Empathetic Perspective: Discussing child support can be tense. The paying parent may worry the money isn’t actually going to the child, and the receiving parent may feel the amount isn’t enough or that they’re bearing more of the day-to-day costs. In high net worth scenarios, these conflicts sometimes amplify – e.g., debates over private school tuition, expensive summer programs, or the cost of a nanny. It’s important to remember the intention: child support is for the child’s benefit. Virginia law wants children to continue to be supported as if their parents were still together, to the extent possible. For the parent writing the checks, it may help to detail how the funds contribute to the child’s life (housing, food, activities, college savings, etc.). For the parent receiving the support, maintaining transparency and communication about the child’s expenses can build trust and reduce resentment. The good news is that Northern Virginia has many resources – from online child support calculators to experienced mediators (see Chapter 4) – that can help parents reach a fair agreement without a bitter court fight. Many high-income parents in Tysons Corner choose to negotiate arrangements such as funding a trust for the child or agreeing to share certain big-ticket expenses (e.g., each parent paying 50% of private school tuition), which can be incorporated into the support order for clarity.

3.2. Spousal Support (Alimony) Disputes

While child support is driven by formulas and the principle of meeting children’s needs, spousal support in Virginia is a bit more discretionary and often fiercely debated in high-net-worth divorces. Spousal support (also called alimony or maintenance) is money paid by the higher-earning spouse to the lower- or non-earning spouse, aimed at allowing both parties to maintain a standard of living reasonably close to what they had during the marriage (at least in theory) or to support the recipient until they can become self-sufficient. In Tysons Corner’s high-income divorces, alimony can involve large sums and complicated considerations, so let’s break down how it works and what recent developments are important.

Factors for Awarding Spousal Support: Virginia law (Va. Code § 20-107.1) lays out numerous factors that courts must weigh in deciding whether to award spousal support, how much, and for how long. Some of the key factors include: the duration of the marriage, the monetary and non-monetary contributions of each party to the well-being of the family, the age and health of both parties, the standard of living established during the marriage, the earning capacity, job skills, and employability of both spouses, and the decisions regarding employment, education, and parenting made during the marriage (for example, a spouse who gave up a career to raise children). Also, marital misconduct (like adultery) can bar a spouse from receiving alimony except in rare cases of manifest injustice – Virginia is somewhat traditional in that regard – but assuming no disqualifying bad behavior, the decision comes down to those multifaceted factors.

In high net worth cases, let’s consider what this means. Imagine a couple married for 20+ years in Tysons, where one spouse was a senior executive and the other was a stay-at-home parent or worked part-time. The long-term marriage and the affluent lifestyle (a nice home, vacations, a country club, etc.) would weigh in favor of a significant spousal support award to avoid a drastic change in the supported spouse’s life. The contributions factor recognizes that being a homemaker and primary caregiver is as important as earning a paycheck – Virginia law explicitly values non-monetary contributions. So, a spouse who managed the household and indirectly supported the breadwinner’s career is entitled to have that sacrifice considered. The earning capacity factor is crucial: if one spouse has a much higher income or earning potential (perhaps they’re a tech entrepreneur or a surgeon) and the other has outdated skills or sacrificed career advancement, the latter’s need and the former’s ability to pay are evident.

Amount and Duration: There isn’t a formula for spousal support in Virginia like there is for child support (except for temporary support guidelines in very limited circumstances). Instead, judges use those factors to craft an award. In practice, for high-income couples, spousal support can be a very large monthly payment, sometimes several thousand dollars, even five figures per month, especially if needed to cover things like housing, insurance, and personal expenses at the marital standard of living. The duration of support can range from a few years (rehabilitative support to help the recipient obtain job training or education) to indefinite (permanent) support. In marriages that lasted 20 or 30 years, it’s not uncommon for Virginia courts to award indefinite support – meaning it continues until either the recipient dies, remarries, or the court orders a change. For example, in a divorce after a 30-year marriage where one spouse was a high-powered lawyer and the other left the workforce decades ago to raise children, a court might decide it’s equitable for the ex-lawyer to pay alimony indefinitely, because the other spouse may never be able to attain a similar standard of living or income on their own. That said, “indefinite” doesn’t always mean “until death” – it just means no fixed end date. The paying spouse can later ask the court to terminate or reduce support if circumstances change (more on that shortly).

It’s also worth noting that, in negotiating settlements, the parties might sometimes agree to a lump-sum buyout or a structured payout for a certain number of years, which provides certainty and a clean break. High-net-worth individuals sometimes prefer a lump-sum or property transfer (such as giving a larger share of investment assets) in lieu of a long-term alimony stream to avoid ongoing entanglement. Any such agreement can be approved by the court if both parties agree it is fair.

Retirement and Changing Circumstances: One hot-button issue in spousal support is the payor’s retirement. People naturally can’t work forever, and high earners often wish to retire at some point, but if they have a large alimony obligation, they might feel chained to their job. Virginia law was amended in recent years to acknowledge this concern: reaching full retirement age (as defined by Social Security) is considered a material change in circumstances for purposes of modifying spousal support. In other words, when a payor spouse hits retirement age, that milestone alone entitles them to at least get a hearing on adjusting support. The court still looks at the specifics – was the retirement actually taken, is it voluntary or forced, what are the financial impacts – but it can’t simply say “you must keep working to pay alimony.” In a 2024 appellate case, Baker v. Baker, the husband retired at 70 and sought to reduce his spousal support. The trial court initially refused, seemingly placing blame on him for not having saved enough for retirement and expecting him to continue earning as before. The Court of Appeals reversed that decision. The appellate court, citing the law and common sense, said that “planning and providing for retirement is not the responsibility of one spouse” and a court shouldn’t force someone of retirement age to keep working just to pay alimony absent evidence that the retirement is in bad faith. In fact, the panel in Baker noted that both spouses bear responsibility for their financial decisions over a long marriage, and it was wrong to make the husband solely accountable for the lack of retirement savings. They emphasized that each case depends on its facts, but there is no bright-line rule requiring a person to forgo retirement to meet support obligations. This was a reassuring development for older payors – you can retire, and the courts should reasonably adjust support if your income drops for a legitimate retirement. (On the flip side, if a much younger person “retires” extremely early just to avoid alimony, courts will likely view that as a voluntary impoverishment and not grant relief – each situation is judged on reasonableness and good faith.)

Besides retirement, other changes that can warrant modifying spousal support include a significant change in either party’s income (say the payor’s income dramatically declines, or the recipient starts earning a lot more), health issues, or changes in the recipient’s needs. One event that automatically terminates spousal support in Virginia (unless the divorce agreement says otherwise) is the recipient’s remarriage. Also, if the recipient cohabitates with another partner in a marriage-like relationship for a year or more, the payor can ask the court to terminate support, under Virginia law. These provisions prevent a supported ex-spouse from having someone new support them while still receiving alimony from the former spouse.

Spousal Support vs. Property Division: In some high-net-worth divorces, the interplay between asset distribution and alimony is an interesting aspect. For example, if one spouse gets a much bigger slice of the marital property (say, investment accounts or real estate) in the divorce, that spouse might not need as much (or any) spousal support. Alternatively, if the marital assets are mostly tied up in a business that one spouse will keep, the other spouse might get more support to balance things out. Virginia courts can award what’s called a “reservation” – the right of a spouse to seek spousal support in the future, even if none is awarded at the moment – which is sometimes used if, for instance, the spouse doesn’t need alimony now because they got plenty of assets, but those assets might run out. In high-net-worth cases, however, support is usually addressed more immediately and in a finite way because the resources are known.

Tax Considerations: As mentioned, the tax treatment of alimony changed due to federal law in 2019. Alimony payments are no longer tax-deductible by the payor nor considered taxable income to the recipient. This contrasts with pre-2019 divorces, where a high earner could deduct a $10k monthly alimony payment, and the recipient would have to pay taxes on $10k as income. Now, the payor gets no deduction, so the true cost of each dollar paid to them is higher, and the recipient doesn’t owe taxes, making each dollar received more valuable. This shift tends to push payors to seek lower amounts (since they can’t offset taxes), and recipients arguably need a bit less to net the same effect. In negotiating high-value alimony, attorneys in Tysons Corner are very attuned to this – sometimes structuring support as part of equitable distribution (which can have different tax implications) or otherwise adjusting the amounts to account for tax impact. It’s a complicated area where advice from both a lawyer and a tax professional is wise.

Emotions and Practicalities: Being asked to pay spousal support, especially indefinite support, can be a bitter pill for some – they may feel, “I worked hard for this money, why should I support my ex indefinitely?” On the other side, the recipient may feel, “I sacrificed my career to support you and our family, it’s only fair you help me now.” Both perspectives have merit, which is exactly why Virginia law tries to weigh everything and find a fair balance. In Tysons Corner’s high net divorces, often there’s room for creative solutions: maybe a larger upfront property award instead of long-term payments, or maybe an agreement to fund, say, an education program for the recipient to refresh their skills, combined with shorter-term support. Mediation (see next chapter) can be very useful here to tailor spousal support in a way both can live with.

A heartening note: the purpose of spousal support, at its core, is to prevent unfair economic consequences of divorce. If one spouse walks away very well-off and the other in poverty or a drastically reduced lifestyle, support is the tool to level the scales. Courts in Fairfax County and Virginia generally don’t want to impoverish anyone or unduly enrich anyone – they aim for fairness. By approaching the issue with a clear understanding of your finances and a focus on transition (how can both spouses be set on a path to financial stability?), you can often reach a spousal support arrangement that, while maybe not delightful, is acceptable. And remember, spousal support isn’t about punishing a spouse (even if emotions say “they caused the divorce!” – except in cases of adultery, fault generally doesn’t drive support decisions). It’s about acknowledging a partnership’s economic intertwinement and unwinding it as justly as possible.

Chapter 4: Mediation as a Path to Resolution

Not every family law battle needs to be fought in court. In fact, for many families in Tysons Corner, mediation offers a way to resolve divorce, custody, and support disputes with less acrimony, more privacy, and often lower cost. Given the high stakes and intensely personal issues at hand – your children, your home, your finances – it’s understandable to feel anxious or combative. But Virginia encourages families to consider mediation as an alternative to a courtroom showdown. In this chapter, we’ll explore what mediation is, how it works in Virginia family cases, and why it can be particularly beneficial (or, in some cases, not suitable) for high-net-worth and high-conflict situations.

What is Mediation? Mediation is a form of alternative dispute resolution in which a neutral third-party mediator helps spouses (or parents) communicate and reach a mutually acceptable agreement. The mediator doesn’t take sides or make decisions; instead, they facilitate discussion, help clarify issues, and suggest potential compromises. Mediation sessions are confidential – what is said in mediation generally can’t be used in court later, which helps people speak more freely. The goal is to arrive at a written settlement (for property division, support, custody, etc.) that both parties sign off on, which can then be presented to a judge and usually approved as a final order.

Voluntary vs. Court-Referred: In Virginia, mediation is not mandatory in divorce or custody cases. You cannot be forced to settle your case in mediation. However, judges have the authority to refer parties to a dispute resolution orientation session – basically an informational meeting about mediation. In fact, for custody and visitation matters, Virginia law (Va. Code § 20-124.4) says the court shall refer the parents to an orientation session with a certified mediator, unless there’s a history of family abuse that would make mediation inappropriate. This orientation is provided at no cost to the parties. The idea is to educate parents about what mediation is and its benefits, so they will choose to proceed with mediation. After the orientation, it’s up to the parties whether to proceed; the judge cannot order you to actually mediate – both sides have to agree to try it.

In practice, in Fairfax County courts, it’s common for judges early in the process to say, “Why don’t you all attend mediation orientation and see if you can work some of this out?” If both parties are open to it, they might then schedule a mediation. If an agreement is not reached by a certain time (often before the next court date), the case just continues on the litigation track. Essentially, mediation offers a chance to resolve issues sooner and with less rancor, but it runs in parallel with the court case if needed.

Why Consider Mediation? For high-net-worth families and those with children, mediation has several advantages:

- Empowerment and Control: In mediation, you (the spouses/parents) have the decision-making power, not a judge. You can craft creative solutions that a court might not impose. For instance, you might agree to keep a jointly owned property in the family trust for a few years before selling, or devise a unique custody schedule that suits your work commitments. Mediators can help brainstorm options. Many parents prefer to make their own decisions about their children rather than have a judge who barely knows the family make those decisions – mediation gives them that opportunity.

- Less Adversarial: By its nature, mediation is more cooperative and less confrontational than the court. Instead of “us vs. them” litigation, the mindset is “let’s solve this together.” This can significantly reduce emotional stress. It’s especially important when children are involved, because an adversarial court fight can deepen the conflict between parents, making co-parenting harder. Mediation sessions, on the other hand, encourage communication. Parents often find that, through mediation, they come to a better understanding of each other’s concerns, which can lay a foundation for better co-parenting post-divorce.

- Privacy: Court proceedings are public record. Anyone could theoretically sit in your trial or obtain the filings (unless sealed). High net worth individuals often value privacy – they don’t want sensitive financial details or embarrassing personal issues made public. Mediation, conversely, is private and confidential. What you disclose in mediation (your net worth, the fact that you have a medical condition, etc.) stays behind closed doors. If confidentiality is a priority (as it is for many Tysons Corner executives, public figures, or simply private families), mediation is a godsend. It allows you to negotiate things like the division of a business or support amounts without airing it in a public forum.

- Time and Cost Efficiency: A protracted court battle in a complex divorce can take months or even years and rack up huge legal fees. Mediation can be much faster – sometimes an agreement is reached in a matter of weeks after a few sessions. Even if you still use attorneys as advisors, the billable hours are typically far less than preparing for trial. One source notes that mediated divorces tend to save couples time and money compared to full litigation. And time saved is emotional energy saved too – moving on with life sooner is often better for everyone’s well-being.

- Tailored Outcomes: Mediators experienced in family law (and many in Northern Virginia are retired judges or seasoned attorneys themselves) can help craft detailed agreements that fit your family. Want to specify who claims the children for tax purposes each year? You can mediate that. Want to ensure a child with special needs has certain trusts or funds set aside? You can include that. Courts might not think of or have the time to incorporate all these nuances, but in mediation, you can address them.

When Mediation Might Not Work: Mediation is not a cure-all, and it’s not appropriate in every case. If there has been domestic violence or abuse, putting the victim in a room to negotiate with the abuser is generally not advisable (and in such cases, courts typically won’t push mediation). Likewise, if one party has a significant power imbalance over the other – maybe one spouse is extremely domineering or the other is too afraid to speak up – mediation could result in an unfair agreement, so caution is needed. In those situations, having attorneys advocate in court may be safer. Also, if one person is hiding assets or being dishonest, mediation can fail because it relies on transparent information exchange.

Additionally, both parties have to be somewhat willing to compromise. If either spouse is utterly entrenched (“I’ll never pay a dime of alimony” or “I want full custody and nothing less”), mediation can still help soften stances, but if it doesn’t, then litigation might be inevitable. Sometimes, couples will attempt mediation and realize that they’re too far apart on key issues – but even then, the process often isn’t wasted, because they might have at least narrowed the issues or understood each other’s positions better.

Mediation Process in Tysons Corner: If you choose mediation, you can hire a private mediator (many family law attorneys in the area offer mediation services, or you can use a mediation firm). The cost could be an hourly fee or flat fee per session. Alternatively, the court can refer you to court-connected mediation programs that may be low-cost or sliding-scale. The typical process begins with an orientation session (either court-referred or arranged by you) that explains the rules and has both parties sign a mediation agreement (which often includes confidentiality clauses). Then you have one or more sessions – nowadays, even Zoom mediations are common, which can be convenient if parties are in different locations or to reduce face-to-face tension.

During mediation, you can choose to have your lawyer present or not. Some mediations involve only the parties and the mediator, and each party consults their lawyer outside of sessions. In more complex cases, having lawyers in the room (or a virtual one) can be helpful for providing immediate legal counsel or reality checks before an agreement is inked. In high net worth cases, you might also involve neutral experts – for example, a CPA might join a session to explain tax implications of dividing stock options, or a child specialist might weigh in on a proposed custody schedule. Mediation is flexible that way.

If an agreement is reached, the mediator (or one of the lawyers) will typically draft a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or a full Property Settlement Agreement (PSA) detailing all the terms. Both parties would review and sign it, and then it could be submitted to the court for incorporation into the final divorce decree or custody order. At that point, it becomes binding and enforceable like any court order.

Benefits for High Net Worth and Family Cases: Given the complexity of high-net-worth divorces (as we saw in Chapters 1 and 3), mediation offers a safe space to discuss intricate financial arrangements. For example, if dividing a family business, the couple might agree in mediation to a specific valuation method or to retain shared ownership post-divorce with clear rules – something a court might be reluctant to order, but that parties can agree to. Mediation also keeps the family’s financial info private (no public court testimony about assets). For custody, parents can get very granular in mediation: they might create a unique schedule that fits around a parent’s frequent business travels or agree to use a co-parenting app for communication – details a judge wouldn’t dictate. Because Tysons Corner families often have demanding careers, mediation scheduling can be more flexible than court dates; you can meet on evenings or weekends if needed, rather than taking days off for court.

And consider the emotional side: divorce or custody fights can take a toll not just on the couple but on the children as well. Seeing parents embroiled in conflict is damaging for kids. Mediation, by reducing conflict, indirectly benefits children. Parents who mediate are more likely to maintain a civil relationship, which benefits co-parenting. They’ve practiced compromising and listening, which are key skills they will need as they continue to jointly raise their kids after the divorce. Virginia’s public policy is to encourage alternative dispute resolution for these reasons – it’s actually written into the custody code that “mediation shall be used as an alternative to litigation where appropriate”. Fairfax County even designates certain days where a retired judge mediator is available at the courthouse for settlement conferences, trying to resolve cases before trial.

Reality Check: While I’m a big proponent of mediation, let’s be candid – it requires good faith. You have to come to the table willing to disclose information honestly and consider compromise. If one spouse is secretly moving money or a parent is dead-set on “winning” custody to hurt the other parent, mediation will be hard. It’s not a sign of weakness to mediate; it doesn’t mean you’re giving in. In fact, reaching a fair agreement out of court often leaves both parties more satisfied than a court order, in which neither side gets exactly what they wanted. Mediation can also preserve relationships – important when, for instance, you will both be at your child’s graduation or wedding someday.

When Mediation Succeeds: To share a quick, anonymized example, a Tysons Corner couple had a high-net-worth divorce with young children. They started off barely able to speak to each other, hurt and angry. Through mediation, they gradually sorted out their finances – dividing their property and investments in a tax-efficient way – and even established a generous education trust for the children. On custody, they realized they both truly wanted the kids to be okay, and they crafted a schedule that accommodated the father’s frequent business trips and the mother’s preference for consistency on school nights. They also agreed to use a shared online calendar and to alternate spending major holidays with the kids. None of this was easy, but the mediator kept them focused on the future rather than past grievances. In the end, they avoided a trial, saved a lot on legal fees, and reached an agreement they could both live with. More importantly, they laid the groundwork for a respectful co-parenting relationship – something that benefits the whole family. This story is not uncommon; many families in Fairfax and the broader Northern Virginia area have found mediation to be a constructive way through an inherently difficult time.

Mediation Resources: If you’re considering mediation in Tysons Corner, there are many resources available. The Fairfax County Circuit Court offers a list of certified family mediators. Organizations like the Northern Virginia Mediation Service provide affordable mediation services. Many law firms (as we saw with Holcomb Law and others) have mediation as part of their practice. It might be helpful to attend the court’s orientation session or even an informational workshop on mediation to get more comfortable with the idea.

In summary, mediation is about finding common ground and reducing the collateral damage of family disputes. Virginia’s legal framework supports it, and the local legal culture in Tysons Corner – which is used to high-stakes cases – often treats mediation as a first step rather than a last resort. As one legal blog noted, judges may recommend that a couple mediate first before resorting to litigation, because a mediated divorce can save time, money, and emotional energy, and it keeps the power with the family rather than with the court. For many families, that recommendation is worth taking.

Chapter 5: Conclusion – Moving Forward for Tysons Corner Families

Family law issues like divorce, child custody, and support can be among the most challenging experiences a person will face. When a family from Tysons Corner – or anywhere – is in the midst of these legal battles, it can feel all-consuming. Yet, as we’ve explored, Virginia’s legal system provides tools and guidelines to achieve fair, well-being-focused resolutions.

For high-net-worth individuals in Tysons, a divorce doesn’t have to mean financial ruin or endless courtroom warfare. Understanding the concept of equitable distribution and the importance of documentation and expert valuation can lead to a property settlement that reflects each spouse’s contributions to the marriage. Yes, you may have to part with a significant share of your assets, but ideally in a way that allows both parties to maintain their lifestyles and feel their contributions have been acknowledged. With knowledgeable legal counsel, complex assets can be handled methodically – businesses appraised, retirement accounts divided by QDROs, trusts and tax implications managed. The key is to engage in the process with eyes open and a willingness to be transparent.

When it comes to children, Virginia law is firmly on the side of what helps the kids thrive. As a parent, you serve your children best (and actually strengthen your case in court) by showing a collaborative spirit and focusing on the children’s needs above all. The phrase “best interests of the child” is not just legal jargon – it’s a reminder that the littlest family members have the most at stake. If you approach custody discussions (whether in mediation or court) with a child-centric view – thinking about their routine, their emotional security, their relationships with both mom and dad – you’re already on the right track. Tysons Corner parents often have demanding careers, but the effort you put into co-parenting cooperatively post-divorce will pay dividends in your children’s happiness and adjustment. And remember, the law does not favor one parent over the other based on gender or traditional roles; today’s fathers often get joint or primary custody, and mothers are recognized for both their caregiving and professional roles. It truly comes down to parenting quality and circumstances, not stereotypes.

For those facing support disputes, know that Virginia’s approach is intended to be reasonable and fact-based. Child support in high-income cases is now more formula-driven up to a high threshold, which adds predictability. While writing a big check each month is never enjoyable, you can take solace in the fact that it’s based on concrete guidelines and aimed at giving your children comparable homes and opportunities in both households. For spousal support, it may feel like an obligation that extends your connection to an ex-spouse for years – but it’s also an acknowledgment of the partnership you had. Especially in long marriages, both spouses contribute in their own ways to the family’s success; spousal support is a way to continue sharing that success so no one person is unfairly left behind. Laws and recent cases in Virginia have trended towards fairness for both sides – allowing payors to retire when the time comes, and ensuring recipients aren’t left destitute due to sacrifices made for the family. With the advice of a seasoned family law attorney, you can negotiate or litigate support terms that make sense given your financial reality and future plans.

One overarching theme through all these topics is the benefit of communication and compromise. It might sound idealistic when you’re hurt or angry, but if you can find a way to talk – directly or through professionals – many solutions open up. Mediation, as we discussed, is one avenue to do that, and it has helped countless Virginia families reach durable agreements while preserving civility. It’s worth considering seriously; even high-conflict couples often find they can agree on practical matters when guided by a skilled mediator.

It’s also important to lean on support networks – not just legal and financial professionals, but also emotional support. Tysons Corner and the greater Fairfax area offer resources such as divorce support groups, counselors and therapists specializing in co-parenting, and financial planners who can assist with the transition to single life. High net worth individuals might feel a stigma about seeking help (“I’m a CEO, I handle big deals, why can’t I handle my own divorce?”), But divorce is not just a legal event; it’s a major life change. It’s okay to seek guidance in navigating it.

As you move forward, keep the long view in mind. The divorce or custody process, painful as it is, will eventually end. You will come out the other side. The relationships – you as co-parents, you with your children – will continue and can even improve once the legal battles are done. The financial puzzle will be sorted out – assets divided, support set – and you’ll have a clearer picture of your new reality, which you can then work with and plan around. Many people find that once the dust settles, they are relieved to have certainty and can focus on rebuilding or starting fresh. And if something truly isn’t working, the law provides mechanisms (appeals in rare cases, or modifications down the line) to adjust; you’re not without recourse if life throws new curveballs.

In closing, family law matters in Tysons Corner combine the universal challenges of divorce and parenting with some unique local twists – high incomes, professional lifestyles, valuable assets. But the principles and values underlying Virginia’s family laws – fairness, the child’s welfare, encouragement of agreement, and equitable solutions – provide a strong foundation for resolving these issues. By staying informed (as you’ve done by reading this article), being proactive, and treating the process and the other party with respect, you put yourself in the best position for a favorable and livable outcome. No one “wins” a divorce in an absolute sense, but you can emerge with your dignity intact, your finances orderly, and your family’s well-being protected.

Remember: You don’t have to go it alone. Consult with qualified Virginia family law attorneys early – their expertise, especially in high-net-worth and contested cases, is invaluable. They can advise you of your rights (for instance, what a fair split might look like, or how the latest case law applies to you) and responsibilities (like financial disclosure requirements, or not relocating children without permission). They can also be your voice in negotiations or court, which sometimes helps keep the personal tensions at bay.

Most importantly, keep your children (if you have them) at the heart of every decision. Court orders will eventually be just paper; parent-child relationships last a lifetime. Tysons Corner might be a bustling economic hub, but at home, every family faces the same fundamental needs: love, stability, and understanding. Virginia’s family laws, supported by recent case precedents, aim to address these needs through fair legal processes. With knowledge, empathy, and sound guidance, you can navigate the storm and find calmer waters for you and your family’s future.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

- Bean, C. L., & Paschke, L. (2025, October 23). Updated Virginia child support laws and the impact on high-income families. Bean, Kinney & Korman.

- Best Husband, G. A. (2025, February 21). 5 Things you should know about a high net worth divorce in Virginia. G. Best Husband Law, PLLC.

- Code of Virginia § 20-107.3 (2026). Court may decree as to property and debts of the parties. (Equitable distribution statute outlining marital, separate, and hybrid property definitions.)

- Code of Virginia § 20-109(E) (2023). Modification of spousal support upon retirement. (Provides that reaching full retirement age constitutes a material change in circumstances for support modification.)

- Code of Virginia § 20-124.3 (2026). Best interests of the child; visitation. (Lists the factors courts must consider in determining child custody.)

- Code of Virginia § 20-124.4 (2026). Mediation. (Requires courts to refer parties to a dispute resolution orientation session in custody/visitation cases, absent abuse.)

- Holcomb Law, P.C. (n.d.). Is mediation mandatory in Virginia?

- Hurston, N. (2024, April 3). Virginia court wrongly held husband responsible for retirement planning. The Daily Record – Maryland Family Law News.

- Garrett v. Hanna, No. 1276-23-3 (Va. Ct. App. Sept. 24, 2024). (Affirmed change of child custody to father; material change in circumstances and best interests of child)

- Herbert v. Joubert, No. 1847-22-4 (Va. Ct. App. Feb. 25, 2025). (Held that forgiven PPP loans count as income for child support)

- Spaid v. Spaid, 2023 Va. Ct. App. (Addressed classification of marital vs. separate property and increases in home value during marriage)

- Baker v. Baker, 2024 Va. Ct. App. (Reversed trial court; allowed spousal support reduction for retired husband, emphasizing shared retirement responsibility)

- Smith Strong, PLC. (2024). Virginia court upholds custody modification based on material change in circumstances. (Summary of Garrett v. Hanna, Va. Court of Appeals)

- Smith Strong, PLC. (2025). Forgiven PPP loans count as income for child support calculations, Virginia court holds. (Summary of Herbert v. Joubert, Va. Court of Appeals)

- General Counsel, P.C. (2023, Feb 2). Virginia Court of Appeals makes equitable distribution decision for family home. General Counsel Practical Counsel Blog.