Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

Commercial construction projects in Northern Virginia often end up in court over contract breaches, construction defects, code violations, or zoning conflicts. As an attorney practicing in Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, Arlington, Clarke, and Frederick counties, I’ve seen how disputes ranging from unpaid invoices to structural failures and zoning battles get resolved (or exacerbated) through litigation. This overview highlights common issues – contract disputes, soil and structural problems, faulty electrical/plumbing/alarm systems, construction defects, and land use zoning fights – with high-level reviews of notable cases and Virginia law. The takeaway: thorough contracts, code compliance, and proactive legal strategy are vital to protect your investment.(By Anthony I. Shin, Esq.)

Table of Contents

- Contract Disputes in Commercial Construction

- Soil and Structural Issues: Foundations to Failures

- Defective Workmanship: Electrical, Plumbing, and Alarm System Problems

- Construction Defect Litigation and Virginia’s Legal Barriers

- Zoning and Land Use Disputes

- Conclusion: Lessons for Builders and Owners

- References

Contract Disputes in Commercial Construction

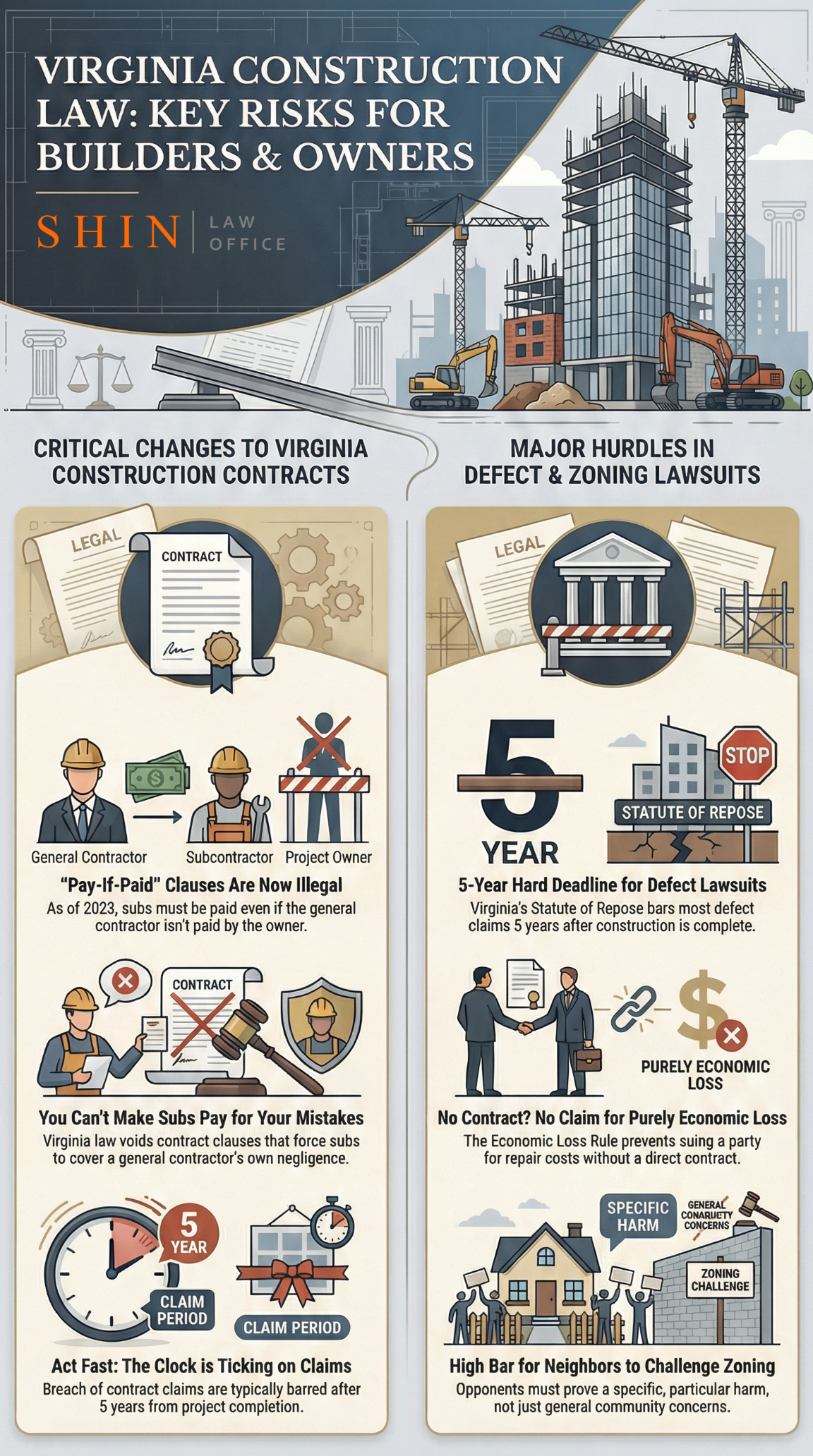

Construction contract disputes are a staple of litigation in Fairfax, Loudoun, and surrounding counties. I frequently handle cases where developers, general contractors, and subcontractors clash over payment, delays, or scope changes. In Virginia, a party’s failure to fulfill the terms of a construction contract (for example, a contractor not completing work, or an owner not paying on time) is a breach that can entitle the wronged party to expectation damages – essentially, the cost to put them in the position as if the contract had been performed. I’ve seen disputes over “pay-when-paid” clauses (the timing of payment from the owner to the GC to subs) and indemnification clauses (one party agreeing to cover the other’s liability). Notably, Virginia law has evolved on these issues in recent years:

- No Indemnity for Your Own Negligence: Virginia’s anti-indemnity statute (Va. Code § 11-4.1) makes it void to contractually require a subcontractor to indemnify (cover) a general contractor for the GC’s own negligence. In a recent Fairfax County case, Fortune-Johnson, Inc. v. QFS, LLC (2025), a general contractor was sued for defective construction (leaky balconies causing water damage) and tried to invoke broad indemnity clauses against its subs. The Virginia Court of Appeals struck down those clauses, refusing to “blue pencil” or save any language that, on its face, made subs pay for the GC’s negligence. The court affirmed that any indemnity provision protecting an indemnitee from its own negligence is unenforceable under Virginia law. In plain terms, if you’re a contractor in Virginia, you cannot shift liability for your mistakes onto your subs by contract – that clause won’t hold up in court.

- “Pay-If-Paid” Clauses Banned: Historically, Virginia allowed “pay-if-paid” clauses, under which a subcontractor is paid only if the GC is paid by the owner (a harsh risk shift upheld in Galloway Corp. v. S.B. Ballard Const. Co., 250 Va. 493 (1995)). However, effective January 1, 2023, the General Assembly banned pay-if-paid clauses in both private and public construction contracts. Under Va. Code § 11-4.6, every construction contract must ensure payment to lower-tier contractors within a set time (60 days of finishing work, or 7 days after the higher-tier is paid, whichever is sooner). In my practice, I’ve had to revise standard contracts to comply with this new law, ensuring subcontractors on Fairfax or Prince William projects aren’t left holding the bag if an owner fails to pay.

- Timeliness and Statutes of Limitations: Construction contract claims are subject to Virginia’s statute of limitations (usually 5 years for written contracts). A vivid example was a case involving Virginia Tech (outside our region but illustrative): the general contractor settled a $3 million construction defect claim with the owner and then sued its subcontractors for indemnity. The Virginia Supreme Court ruled those claims were time-barred – the GC waited too long (over 5 years after project completion) to pursue the subs. As a result, the GC alone ate the $3 million loss. The lesson for Northern Virginia contractors is clear: do not delay in asserting your contract rights. If a project in, say, Loudoun or Arlington has gone south, you must file any breach of contract or indemnity claims within the statutory window, or risk losing them entirely.

In sum, contract disputes require careful navigation of Virginia’s laws. I always counsel clients to get everything in writing (change orders, schedule extensions, payment terms) and to be aware of clauses that might be void. Our courts will enforce clear contracts – but only to the extent they comply with statutes and public policy. When a dispute arises, the party with a well-documented project record and a prompt claim is in the strongest position.

Soil and Structural Issues: Foundations to Failures

Problems with a building’s foundation, soil, or structural integrity can spawn lawsuits across Northern Virginia. In Loudoun and Prince William counties, where development has sprawled into areas with varying geology, I’ve handled cases stemming from unstable soils, erosion, and structural collapses. These “brick-and-mortar” failures often lead to fights over who is responsible – the site engineer, the builder, or perhaps a geotechnical issue beyond anyone’s control.

For example, I saw a case in Prince William’s rural outskirts (Catharpin) where improper grading and drainage led to severe erosion beneath the foundation of a custom commercial structure. The builder blamed “natural soil conditions,” while the owner argued the contractor ignored the engineered site plan – a classic dispute. Such cases often require dueling expert witnesses to determine whether the construction deviated from standards or whether an unforeseen soil condition was to blame. In Clarke County, even on smaller projects, I’ve seen how failing to address site conditions upfront can lead to litigation. One 2025 federal case out of Clarke (Legge v. Clarke County Zoning Dept.) arose from a landowner’s battle over a county decision related to his property’s development – underscoring that soil grading, stormwater management, and related zoning conditions can all intertwine in legal fights.

A high-profile Loudoun County example involved toxic mold from structural defects. In Meng v. Drees Co. (Loudoun Cir. Ct. 2009), a couple’s new $900,000 home developed leaky basement windows; water intrusion led to rampant mold growth, causing health problems for the family. A jury found the builder negligent for shoddy construction and initially awarded $4.75 million in damages – one of the largest mold verdicts in Virginia at the time. The judge later reduced it to about $1.4 million, citing lack of permanent injury, but let the negligence finding stand. The case highlights that structural breaches (e.g., failing to properly seal a foundation or install windows) can make a builder liable for the cascade of damage that follows. It also shows the limits: the court struck the homeowners’ fraud and Virginia Consumer Protection Act claims for insufficient evidence of intentional concealment, reminding us that not every construction problem equates to consumer fraud unless there’s proof that the builder knowingly misled the buyer.

In Fairfax County, many structural defect disputes involve commercial buildings – think of a parking garage deck collapse or a large tenant discovering that the steel beams don’t meet spec. These cases often center on whether the contractor met the standard of care and contract requirements. A recurring legal issue is the economic loss rule (discussed in more detail below): if a structural failure causes only economic loss (the cost to repair the building itself), Virginia law may limit the remedy to contract claims rather than tort. But if the failure causes personal injury or damage to other property, negligence claims may arise. For instance, if a poorly designed retaining wall in Arlington collapses and damages a neighboring property, the neighbor could sue for property damage in tort, since that harm is beyond the contract’s scope.

From a preventive standpoint, I advise clients to invest in soil studies and to adhere strictly to structural plans. It’s cheaper to shore up a weak foundation before construction than to litigate a building collapse after the fact. When disputes do occur, courts in our region will pore over the contracts: Who promised what about soil conditions? Was there a differing site conditions clause? Did the owner rely on the contractor’s expertise for structural design (potentially triggering professional negligence duties), or was it strictly the contractor following given plans? The answers determine liability. Ultimately, Northern Virginia cases teach that groundwork – literally and legally – is key: solid foundations and solid contracts are the best defense against lawsuits over structural and soil issues.

Defective Workmanship: Electrical, Plumbing, and Alarm System Problems

Not all construction defects are as dramatic as a cracked foundation – often it’s the hidden workmanship issues in electrical, mechanical, or life-safety systems that lead to conflict. I’ve handled numerous disputes in Loudoun, Fairfax, and Frederick County buildings where something behind the walls was done wrong. These cases include improper wiring, faulty plumbing that causes leaks, and alarm and sprinkler systems that don’t function when needed.

In Leesburg (Loudoun County) recently, I represented a commercial property buyer who discovered after closing that the building’s fire alarm system was non-compliant. The seller had failed to disclose serious life-safety defects: fire alarms weren’t connected to any monitoring station, the alarm communicators didn’t transmit signals, and there were no records of required annual inspections. The local Fire Marshal hit the new owner with violations that the previous owner had “conveniently” omitted from the sales documents. This situation quickly moved from a code-compliance headache to a legal claim – we filed suit alleging the seller’s breach of contract and fraud for failing to disclose the known alarm system issues. In Loudoun (and all of Virginia), sellers of commercial property generally aren’t under the same strict disclosure duties as residential sellers, so we had to base our case on specific contract representations and any evidence that the seller actively hid problems. We uncovered emails and old inspection reports showing the seller was aware of the alarm failures. That case settled with the seller paying most of the remediation cost to get the building up to code – a win that likely saved my client’s business, since a non-compliant building can’t legally be occupied.

Electrical and plumbing problems similarly give rise to litigation, though often the damage is purely financial. For instance, if a contractor in Prince William County installed substandard wiring that later had to be completely redone, the owner might sue for the cost of repair and delay. One real example: a data center project in Loudoun had to replace miles of cable because the subcontractor used wire that didn’t meet fire-resistance specs. The owner’s claim was for the cost of replacement and lost profits due to the delay. In such cases, Virginia’s strict economic loss rule looms large – because the losses are economic (the cost to fix the defect and time lost) and not personal injury or other property damage, the owner typically must rely on breach of contract or warranty claims, not negligence. The Supreme Court of Virginia has long held that where defective work only undermines a consumer’s or project owner’s economic expectations, the remedy lies in contract, not tort. In the landmark Sensenbrenner case, homeowners sued an architect in tort for a design flaw that damaged their own house and pool; the Court tossed the claim, calling those losses “disappointed economic expectations” properly addressed by contract law. What this means on a practical level: if a building’s plumbing is installed wrong and only the building itself (or its value) is harmed, you usually can’t sue the plumber for negligence. You’d pursue breach of contract (if in privity) or perhaps a warranty or building code claim. However, if that faulty plumbing floods a neighbor’s store or causes someone to slip and get hurt, now you have damage beyond the contract’s scope – tort claims for property damage or personal injury could be viable.

Another issue I see is code violations and the role of Virginia’s Uniform Statewide Building Code. Local building departments (e.g. Fairfax County’s Land Development Services) can issue notices of violation or even stop-work orders if work isn’t to code. Those administrative actions can escalate into court if not resolved. For example, I had a case in Arlington where a commercial renovation passed final inspection, but later it emerged that an unlicensed electrician had performed much of the work, violating state law. The business owner faced expensive re-inspections and had to bring everything up to code with a licensed contractor. We pursued the original contractor for breach of contract and violation of the Virginia Consumer Protection Act (since they misrepresented that they’d use licensed trades). Code non-compliance often strengthens an owner’s hand in litigation, showing that the work was not just subpar but also illegal or unsafe. Judges in Northern Virginia are keenly aware that construction standards exist to protect the public, and a flagrant code violation by a contractor can even be seen as a per se breach of the duty of care.

Finally, alarm and sprinkler system cases deserve special mention because of the life-safety element. In one Fairfax County matter, a restaurant’s sprinkler system was mistakenly left inoperable after a renovation; a small kitchen fire turned into a major blaze when the sprinklers failed, causing extensive damage to adjacent units. The neighboring businesses sued the restaurant and the contractor. The litigation involved layers of insurance issues, but fundamentally, it hinged on who bore responsibility for the alarm/sprinkler failure. These cases often bring in multiple parties – the installer, the maintenance company, possibly the alarm monitoring service – each pointing fingers. My approach in such complex multi-party cases is to meticulously track contracts and inspection records: who was obligated to test the system? Was there a final acceptance by the owner or fire marshal? Did a monitoring company receive an alert? Answering these questions through documents can make or break the case. In the restaurant fire case, we proved the fire alarm monitoring company had never been reconnected after the construction, despite the contractor’s assurances. That evidence led to a settlement with the contractor’s insurer covering the neighbors’ damages.

Overall, defective workmanship cases in electrical, plumbing, and fire safety systems teach a crucial lesson: details matter. The specific contract terms (e.g. requiring licensed work, compliance with code, passing final inspections) give the roadmap for any lawsuit. And from the contractor’s perspective, following those details – and documenting that you did – is the best way to avoid seeing me on the other side of a courtroom.

Construction Defect Litigation and Virginia’s Legal Barriers

When construction defects do result in lawsuits, Virginia law imposes some unique barriers and defenses that any owner or builder should know. Practicing in Northern Virginia, I always walk clients through these legal doctrines that can make or break a defect case:

- Statute of Repose (5-Year Cutoff): Virginia has one of the stricter statutes of repose for construction-related claims. Under Va. Code § 8.01-250, no action for injury to property (or person) arising from the defective condition of an improvement to real property may be brought more than five years after the construction was done. In plain English, if a building was substantially completed in 2016, any lawsuit for construction defects causing damage has to be filed by 2021, or it’s barred – regardless of when the issue was discovered. This caught many people by surprise because five years is not very long in the life of a building (defects often surface later). The Supreme Court of Virginia underscored the firmness of this rule in Potter v. BFK, Inc. (2021), a case I followed closely. There, a piece of equipment (a stone hopper in a silo) failed after 8 years, causing a fatal accident. The installer argued the claim was barred by the 5-year repose. The plaintiff countered that the hopper was “equipment” (an exception in the statute) rather than an ordinary building part. The Supreme Court agreed with the plaintiff, laying out factors to distinguish equipment from ordinary building materials and allowing the suit to proceed. The Potter case is technical, but its message is clear: the 5-year repose is a brick wall for claims unless you fit within a narrow exception (such as suing a manufacturer of equipment or if the defendant remained in control of the property). For owners in Fairfax or Loudoun, this means you can’t assume you have a decade or more to hold builders accountable – the clock is ticking from the end of construction. And for builders, it means after five years, you gain a significant shield against old claims (though keep in mind, it doesn’t protect you if you stay involved with the property, e.g., as a property manager or if you fraudulently concealed a defect).

- Economic Loss Rule & Lack of Privity: I touched on this earlier – Virginia’s economic loss rule generally prevents plaintiffs from recovering purely economic damages in tort absent contractual privity. In construction defect litigation, this often means that a property owner can’t sue a subcontractor or design professional for negligence if they don’t have a direct contract, unless the defect caused personal injury or property damage to other property. For example, a tenant in Arlington who suffers only economic losses (like lost profits because their store’s roof leaks) typically can’t sue the architect in tort if they have no contract – they’d need to rely on the landlord or someone in privity to pursue the claim. There are some workarounds: Virginia Code § 8.01-223 does allow negligence suits without privity for property damage or personal injury (removing the old privity bar in those scenarios). But it explicitly does not create a cause of action for economic loss. In practice, I explain to clients: if a defect merely requires you to spend money to repair your building, it’s a contract case (or a warranty claim, or perhaps a consumer protection claim if deception is involved). If it injures someone or wrecks other property, it can be a tort case. Understanding this boundary is critical in developing a legal strategy for defect cases.

- Warranty and Consumer Protection Claims: Many commercial construction contracts include express warranties (e.g., a one-year workmanship warranty), and Virginia law also imposes implied warranties in some contexts (for instance, the seller of a new home gives an implied structural warranty under Va. Code § 55.1-357). In the commercial realm, implied warranties are often disclaimed in contracts. But I’ve seen owners get traction by invoking consumer protection laws if a contractor engaged in misrepresentation or fraud. The Virginia Consumer Protection Act (VCPA) can apply to construction services when there’s deception, and it allows for treble damages and attorney’s fees in some cases. In the Loudoun mold case (Meng v. Drees), the homeowners alleged VCPA violations and the jury initially awarded on that basis, but the judge set it aside – perhaps finding no sufficient evidence of a misleading transaction (VCPA usually targets misrepresentations in the sale or lease of goods/services). Nonetheless, in my practice, if a contractor lied about something material (say, claiming a building was “up to code” when it was not), I consider a VCPA count as a pressure tactic. It’s not applicable in every commercial context (especially if both parties are businesses of equal bargaining power), but it’s part of the arsenal.

- Insurance Coverage Battles: A behind-the-scenes but important aspect of construction defect lawsuits is insurance – specifically, whether the contractor’s commercial general liability (CGL) policy covers the defect. Virginia, for a long time, had a rule that ordinary defective workmanship is not an “occurrence” under a standard CGL policy (meaning the insurer could deny coverage for the repair costs). This is more of an insurance law point than a construction law point, but it affects settlement dynamics. A recent Fourth Circuit case (2022) opened the door slightly by finding coverage where a subcontractor’s defective work caused damage (mold) to other parts of the project. The law here is evolving, but as an attorney, I always assess whether an insurance company will fund the defense or the payout – it often dictates how hard a party will fight.

In Northern Virginia’s courts, judges are cognizant of these legal boundaries. A Fairfax judge once candidly said in a bench trial I had: “I can’t give you what the law doesn’t allow, no matter how sympathetic the situation.” He was referring to an owner who wanted to recover purely economic losses from a third-party engineer – something not allowed without privity. We had to pivot and focus on the breach-of-contract claims we had against the general contractor instead. The bottom line is that construction defect litigation here is a minefield of legal doctrines. Part of my job is guiding clients through that minefield – or better yet, structuring their contracts and responses beforehand to avoid the explosions altogether.

Zoning and Land Use Disputes

Disagreements over zoning, land use, and permits can be just as contentious as those over bricks and mortar. In urbanizing counties like Fairfax and Arlington, and even in more rural counties like Clarke and Frederick, the approval process for commercial buildings often triggers legal challenges. These range from developers suing local governments (or vice versa) to neighbors appealing variances and special use permits. I’ve been involved in a number of these fights, and a few key cases illustrate how they play out:

- Standing of Neighbors to Challenge Development: In Fairfax County, a notable case involved a group of homeowners opposing a zoning decision that allowed a storage facility to be built at a Girl Scout camp in Oakton. The Zoning Administrator had interpreted the zoning ordinance to permit the facility under a special exception, and the Board of Supervisors was inclined to approve it. Nearby residents were unhappy and appealed the Zoning Administrator’s determination to the BZA (Board of Zoning Appeals), which sided with the residents. But when the dispute hit the Fairfax Circuit Court, the judge threw out the BZA’s ruling on the grounds that the neighbors lacked standing in the first place. The court applied the Virginia Supreme Court’s two-part test from Friends of the Rappahannock v. Caroline County (2013) for standing in land use cases: (1) you must own or occupy property close by, and (2) you must show a particularized harm different from the general public. In the Girl Scout camp case, the court said the alleged harms were too speculative – since no actual construction had started, the neighbors couldn’t prove a specific injury yet. Essentially, until the project was approved and something tangible happened, the fear of increased traffic or noise was hypothetical. This case is a caution to community groups: Virginia courts set a high bar for neighbors to intervene in development decisions. Unless you can demonstrate a concrete, particular harm (like “this new building will block the light to my property or flood my yard”), your lawsuit might be dismissed before it ever reaches the merits.

- Challenging County Zoning Actions: Arlington County’s recent “Missing Middle” saga is a prime example of developers and citizens clashing over zoning policy. In 2023, Arlington adopted an Expanded Housing Option (EHO) ordinance – dubbed “Missing Middle” – allowing up to 6 housing units on lots previously zoned for single-family homes. A group of residents sued, claiming the County failed to follow proper procedures and that the upzoning harmed them. In September 2024, the Arlington Circuit Court invalidated the Missing Middle zoning amendment, delivering a win for the opponents. However, that victory was short-lived. On June 24, 2025, the Virginia Court of Appeals overturned the decision, not by declaring the ordinance good, but on procedural grounds. The appeal court found that certain parties (homeowners who had already obtained EHO permits) should have been allowed to intervene in the trial, meaning the lawsuit had to be restarted with those parties included. As of 2026, the Missing Middle battle continues, with further appeals likely. The Arlington case teaches that when it comes to broad zoning changes, litigation can turn on procedural nuances (such as necessary parties and intervention) as much as on the substance. It’s also a reminder that local Circuit Courts might buck a county’s actions, but the final say often rests with higher courts or the legislature. For attorneys like me, it’s fascinating to see traditional single-family zoning being tested in court, as it could set a precedent for other Northern Virginia counties considering ways to increase density.

- Inverse Condemnation and Government Liability: In some situations, a landowner claims that a government’s action (or inaction) effectively took or damaged their property – an inverse condemnation claim under Article I, § 11 of the Virginia Constitution. I handled a matter in Loudoun County where homeowners alleged that a county-approved stormwater management project redirected runoff and flooded their land, amounting to a taking without compensation. Inverse condemnation cases are complex and have special procedural requirements. For one, if you’re suing a county in Virginia, you generally must file a notice of claim within 6 months of the damage (per Va. Code § 15.2-1248) or risk dismissal. In the Loudoun case, an initial hurdle was whether the homeowners complied with that notice requirement – it’s an easy trap to miss. Substantively, the Court of Appeals (in a 2024 unpublished opinion) clarified that you don’t have to prove the government intended to take your property; if the government’s public project directly and substantially damaged your property, you can pursue a claim. The Loudoun homeowners in that case were allowed to proceed by alleging the county’s actions in altering a FEMA floodplain caused predictable damage to their land. In my view, inverse condemnation is a powerful but challenging remedy – powerful because it can get you damages where normally sovereign immunity would shield the government, but challenging because courts demand clear causation and significant harm (minor or speculative impacts won’t qualify as a “taking”). In Clarke and Frederick counties, which are more rural, I’ve seen inverse condemnation claims pop up with things like road expansions or quarry operations that affect nearby land. Each time, the fundamental question is: did the government’s project essentially appropriate a benefit from your property or impose a burden on it that should be compensated?

- Developers vs. Counties – Proffers and Permits: On the flip side, developers sometimes sue the county – for example, if a site plan or building permit is improperly denied or if onerous conditions (proffers) are imposed. These typically take the form of declaratory judgment actions or appeals under Virginia Code § 15.2-2285(F) (for challenging zoning decisions). In Fairfax County, I recall a case in which a developer contested the county’s interpretation of a proffer regarding road improvements, arguing it amounted to an unconstitutional taking of their money (an “exaction” issue). In that instance, the court sided with the county, deferring to the legislative nature of the proffer process. Generally, Virginia courts give local governments considerable deference in zoning unless there’s a clear violation of law or abuse of discretion. As an attorney for developers, I often counsel negotiation and compromise (e.g., amending a plan or seeking a variance) rather than litigation, because suing a county is an uphill battle. That said, there are times when litigation is necessary – such as when a county blatantly misinterprets its ordinances or acts in a way that unfairly singles out a property owner.

Bottom line on zoning disputes: These fights can drag on and become emotionally charged (communities versus developers, etc.), but the courts impose rigorous rules on standing, timeliness, and proof of harm. If you’re a business or developer in Northern Virginia, it pays to do things by the book: secure the proper permits, document your compliance, and engage with any community opposition early. And if you’re a neighbor worried about a project, you must act quickly and gather real evidence of how you’ll be uniquely harmed. As with construction disputes, much of my job in land use cases is managing expectations – sometimes the courtroom is the right venue to resolve a zoning issue, but other times the smarter play is a political or administrative solution (like lobbying the Board of Supervisors or tweaking a proposal to address concerns). When we do have to litigate, we lean on the record: meeting minutes, staff reports, traffic studies, expert testimony on impacts – these become the weapons in court. Northern Virginia judges are not swayed by mere NIMBYism; you need legal and factual heft to overturn a land use decision.

Conclusion: Lessons for Builders and Owners

Reflecting on all these cases and issues across Fairfax, Loudoun, Prince William, Arlington, Clarke, and Frederick counties, a few lessons stand out:

1. Get It in Writing (and Read What’s Written): Many disputes could be avoided or quickly resolved if the parties had clear, well-drafted contracts and adhered to them. Whether it’s a payment schedule, a change order process, or a warranty on workmanship – spell it out. Virginia courts will enforce contracts as written, but they won’t rescue you from a bad deal. And remember, some provisions are unenforceable by law (like indemnity for your own negligence or pay-if-paid terms after 2023). I advise reviewing contracts with counsel, especially for big projects, to ensure they comply with current Virginia law and adequately protect your interests.

2. Document Problems Early: If you’re an owner and see construction issues (leaks, cracks, code violations), don’t wait. Document them, notify the contractor in writing, and consider bringing in an independent inspector. Legally, prompt notice can bolster a breach-of-contract claim and may be required to trigger certain remedies. Plus, the 5-year statute of repose means the clock is ticking from day one. If you’re a contractor and a problem arises, own it and fix it if you can – or at least document why it’s not your fault. I’ve seen many cases turn on one party’s silence or inaction being construed against them.

3. Leverage Expert Advice: Construction and development disputes often hinge on technical details. Engage the right experts – engineers, architects, code specialists, or land use planners – to build your case or defense. In a mold case, a good environmental engineer can establish (or refute) the causation (or lack thereof) of health issues. In a zoning case, a traffic engineer’s report might be the evidence that shows a “particularized harm” or refutes one. In my practice, expert testimony has been the deciding factor in numerous trials.

4. Know the Law or Find a Lawyer Who Does: Virginia construction law is a mix of statutes and court-made doctrines that isn’t always intuitive. For instance, the economic loss rule will bar certain claims even if they feel “fair”. Sovereign immunity and standing can torpedo a lawsuit before it starts. And new laws (like the ban on pay-if-paid) can dramatically change rights and obligations mid-project. Whether you’re a developer, contractor, or property owner, having legal guidance from someone who knows this landscape is invaluable. I often function as both a sword and a shield – helping clients assert their rights forcefully when needed, while also navigating pitfalls and expensive dead ends in litigation.

5. Mitigate and Settle When Sensible: Lastly, not every dispute needs to end up in a court verdict. Especially in the commercial construction world, litigation is a tool, not an end in itself. I’ve negotiated settlements where a project gets finished correctly, an insurance company covers repairs, or a county grants a needed variance – all without protracted court battles. The cases discussed in this article are instructive, but keep in mind that they often represent worst-case scenarios where talks failed. My philosophy is to litigate strategically, only to the extent necessary to achieve the client’s goals. Sometimes, just filing a well-founded lawsuit (with documentation and expert support attached) brings the other side to the table.

Commercial construction is a high-stakes endeavor, and in Northern Virginia’s booming markets, it will likely remain fertile ground for lawsuits. But with careful planning, knowledgeable counsel, and a proactive approach to problems, you can greatly reduce the risk of finding yourself in the courtroom – or if you do end up there, ensure that you are well-armed to protect your investment.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

- Bean, Kinney & Korman. (2015, January 28). Fairfax Circuit Court Limits Homeowners’ Ability to Challenge Zoning Administrator. Real Estate, Land Use & Construction Law Blog.

- Fox & Moghul. (2025, May 15). Understanding the Economic Loss Rule and Privity of Contract in Virginia Construction Law. Fox & Moghul Blog.

- Hosh, K. A. (2009, March 13). Judge Cuts Award in Mold Case: Lack of Permanent Injury Cited; Couple to Get $1.4 Million. The Washington Post.

- KPM Law. (2021, September 7). Statute of Repose: A Recent Case. (Discussing Potter v. BFK, Inc., 2021 Va. LEXIS 87).

- ConsensusDocs. (2022, July 11). Newly Enacted Virginia Legislation Bans “Pay-If-Paid” Clauses in Construction Contracts. (Senate Bill 550, amending Va. Code §§ 2.2-4354, 11-4.6).

- Thomas, Thomas & Hafer LLP. (2026, January 5). Virginia eNotes: Fortune-Johnson, Inc. v. QFS, LLC. (Va. Ct. App. Feb. 25, 2025, enforcing Va. Code § 11-4.1 anti-indemnity clause).

- Shin, A. I. (2023). From Code Violation to Courtroom: When Life Safety Defects Turn Into Lawsuits in Leesburg, VA. Shin Law Office Blog.

- Shin, A. I. (2025). Haymarket Main Street Commercial Fit-Outs: Unapproved Materials and Spec Changes. Shin Law Office Blog.

- Virginia Lawyers Weekly. (2025, September 15). Legge v. Clarke County Zoning Department (Case No. 5:25-cv-00062, W.D. Va. Sept. 4, 2025).

- McGuireWoods LLP. (2025, June 25). Virginia Court of Appeals Overturns Arlington “Missing Middle” Decision. Client Alert (discussing Nordgren v. Arlington County).