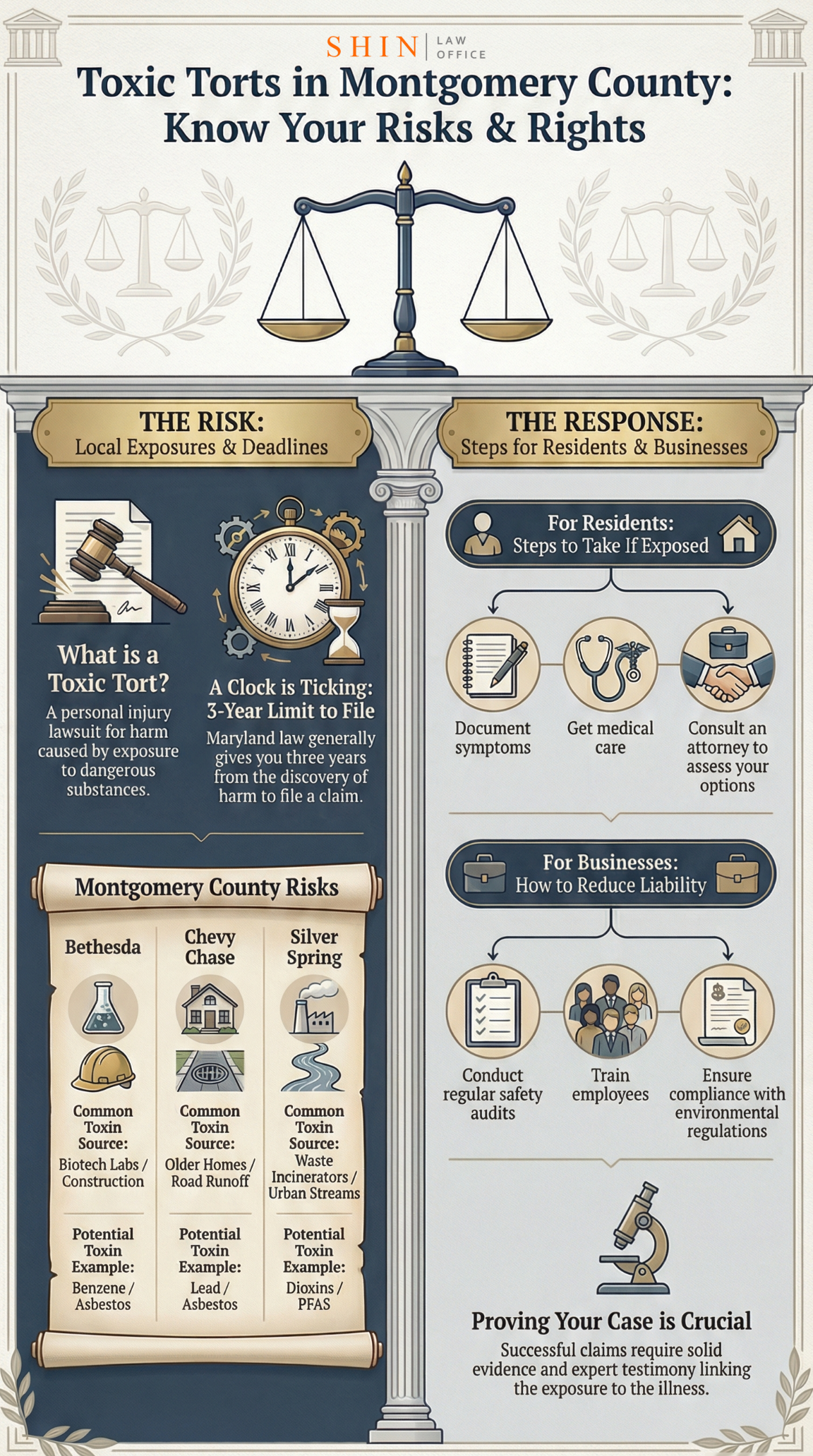

As Basil M. Al-Qaneh, Esq., I’ve spent years helping folks in Montgomery County deal with the fallout from toxic exposures. The bottom line is this: If you’ve been harmed by chemicals or pollutants in places like Bethesda, Chevy Chase, or Silver Spring, whether at home, work, or in your community, you may have grounds for a personal injury claim under Maryland law. These “toxic tort” cases can compensate you for medical bills, lost wages, and suffering, but you generally have three years from discovering the harm to file. Businesses and plants face risks too, like liability for spills or emissions that affect employees or neighbors. Always consult a professional early, as proving exposure and causation requires solid evidence.

Key Points on Toxic Tort Issues in Montgomery County

- Research suggests that toxic tort claims in areas like Bethesda, Chevy Chase, and Silver Spring often stem from environmental exposures such as contaminated water or air pollutants, potentially leading to health issues like respiratory problems or cancer, though proving causation requires expert evidence.

- The evidence points to businesses and residents facing shared risks from industrial activities and aging infrastructure, with Maryland’s three-year statute of limitations emphasizing the need for timely action in personal injury cases.

- Studies indicate that common toxins such as PFAS and dioxins pose ongoing concerns in suburban settings, but proactive prevention and legal recourse can mitigate their impacts on affected parties.

- It seems likely that consulting a local attorney early enhances outcomes, as settlements are common to avoid trials, though contributory negligence in Maryland could bar recovery if the plaintiff shares any fault.

- While not all exposures result in viable claims, community awareness and resources in Montgomery County support equitable resolutions, underscoring the importance of balanced perspectives on environmental health.

Understanding Toxic Torts

As Basil M. Al-Qaneh, Esq., I’ve seen how toxic torts disrupt lives in our vibrant Montgomery County communities. These claims arise when negligent exposure to harmful substances causes injury, entitling the injured person to compensation under Maryland law for medical costs, lost wages, and suffering. In towns like Bethesda, with its biotech hubs, risks include chemical spills; in Chevy Chase, older homes may harbor lead or asbestos; and in Silver Spring, urban runoff and incinerator emissions. Proving negligence involves duty, breach, causation, and damages, often relying on experts to link toxins to health effects.

Impacts and Legal Pathways

Residents may experience short-term symptoms such as irritation, while businesses risk lawsuits for non-compliance and long-term risks such as immune suppression. Maryland’s contributory negligence rule adds complexity—if you’re even slightly at fault, recovery could be denied. Yet, with a three-year discovery window, victims have time to build strong cases, potentially securing uncapped economic damages and capped non-economic awards.

Prevention and Resources

Empower yourself: Test wells, report issues to DEP, and seek free consultations. Businesses should audit regularly to avoid liabilities. Together, we can foster safer neighborhoods.

In Montgomery County, Maryland, toxic tort personal injury issues represent a critical intersection of environmental health, legal accountability, and community well-being, particularly in bustling towns like Bethesda, Chevy Chase, and Silver Spring. As Basil M. Al-Qaneh, Esq., with over two decades advocating for affected residents and businesses, I’ve witnessed the profound effects of these cases—from subtle groundwater contamination to industrial emissions—and the pathways to justice they offer. This comprehensive overview draws on Maryland’s legal framework, recent environmental data, and practical insights to illuminate the challenges and solutions, ensuring readers grasp both the risks and remedies without being overwhelmed by legal jargon.

Toxic torts fall under personal injury law, where plaintiffs seek compensation for harms caused by negligent exposure to dangerous substances. Unlike standard negligence claims, these often involve complex causation proofs that require toxicologists or medical experts to link exposures to illnesses such as cancer or respiratory diseases. In Montgomery County, exposures aren’t limited to heavy industry; suburban sources include PFAS in water supplies, dioxins from waste facilities like Dickerson, and legacy toxins such as lead in pre-1978 homes prevalent in Chevy Chase. Bethesda’s biotech sector adds risks from chemical handling, while Silver Spring’s urban mix amplifies runoff concerns into streams like Sligo Creek.

Maryland’s negligence standards require proving four elements: duty (e.g., a business’s obligation to safely manage chemicals), breach (failing to do so), causation (a direct link to harm), and damages (quantifiable losses). The state’s contributory negligence doctrine—unique among most jurisdictions—bars recovery if the plaintiff is even 1% at fault, as reaffirmed in cases like Coleman v. Soccer Ass’n of Columbia (2013). This strict rule heightens the stakes, making thorough documentation essential. The statute of limitations is generally three years from discovery under Courts & Judicial Proceedings §5-101, with an extension for latent harms. Compensation includes uncapped economic damages (medical bills, lost income) and capped non-economic damages (pain and suffering, at $890,000 for post-2023 claims), with punitive awards rare absent malice.

Residents often face insidious effects: PFAS-linked immune issues or dioxin-related developmental delays, disproportionately impacting lower-income areas in Silver Spring. Businesses, from biotech firms to small manufacturers, grapple with liabilities under respondeat superior for employee negligence and regulatory compliance with MDE and EPA standards. Defenses include lack of notice or open hazards, but juries tend to favor victims in proven cases. Recent examples highlight the urgency: incinerator exceedances prompting state actions, and ongoing PFAS monitoring in county wells.

Filing occurs in Montgomery County Circuit Court for larger claims or District Court for smaller ones, with government suits under the Tort Claims Act requiring one-year notice and $400,000 caps. Most resolve via settlements to bypass trials, leveraging contingency fees where attorneys front costs. Prevention is key: Residents should test wells annually, use low-VOC products, and report via 311; businesses need audits, training, and pollution controls. Resources like DEP (240-777-0311) and advocacy groups such as Sierra Club aid these efforts.

To illustrate common scenarios:

| Scenario | Town Example | Potential Toxin | Legal Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential Exposure | Chevy Chase older homes | Lead paint | Proving landlord knowledge; contributory negligence if ignored warnings |

| Workplace Incident | Bethesda biotech lab | Hazardous chemicals | Employer liability under respondeat superior; OSHA compliance defenses |

| Community Pollution | Silver Spring near the incinerator | Dioxins | Class actions possible; causation via experts |

| Water Contamination | County-wide wells | PFAS | Three-year discovery rule; economic damages for filtration costs |

This table underscores the varied contexts, emphasizing the role of evidence.

Environmental justice emerges as a theme, with disparities in exposure burdens affecting underserved communities, prompting policy advocacy. While Maryland lacks some federal PFAS regulations, local ordinances, such as illicit discharge prohibitions, bolster protections. Case precedents, such as premises liability rulings requiring knowledge of hazards, inform strategies—e.g., in slip-and-falls, analogous to unnoticed spills that mirror undetected leaks.

Ultimately, toxic torts in Montgomery County highlight the need for vigilance: From documenting symptoms to engaging experts, informed action turns challenges into opportunities for redress and prevention. If affected, a free consultation can clarify your path forward.

BLUF: The Essentials on Toxic Torts in Montgomery County

If you’re a resident, business owner, or worker in Bethesda, Chevy Chase, or Silver Spring dealing with potential toxic exposure, here’s the core message: Maryland law allows you to pursue compensation for injuries from negligent handling of harmful substances, but time is limited (three years from discovery). Residents often face water or air pollution issues, while businesses and plants risk lawsuits for emissions or spills. Recent local concerns, like dioxin emissions from the Dickerson incinerator, highlight the need for vigilance. Proving a claim requires linking exposure to harm, but successful cases can cover medical costs and more. Businesses can mitigate risks with compliance; residents can monitor health and report issues. Overall, while risks exist, proactive steps and legal support make a big difference. Don’t wait if symptoms appear.

Table of Contents

- What Are Toxic Torts and Why Do They Matter Here?

- Common Sources of Toxic Exposure in Bethesda, Chevy Chase, and Silver Spring

- How Toxic Exposures Affect Residents’ Health and Lives

- Challenges for Businesses, Industrial Sites, and Manufacturing Plants

- Your Legal Rights: Filing a Claim in Maryland

- Prevention Tips and Resources for a Safer Community

- References

Chapter 1: What Are Toxic Torts and Why Do They Matter Here?

Let me start simple: A toxic tort is basically a lawsuit where someone claims they’ve been hurt by exposure to dangerous chemicals or substances. It’s a type of personal injury case focused on toxins such as asbestos, pesticides, or air or water pollutants. In Montgomery County, these aren’t rare blockbuster events; they’re often subtle, building over time from everyday sources.

Why does this hit home in our area? Bethesda, with its research labs and NIH, has potential for chemical handling risks. Chevy Chase, being more residential, faces issues such as lead in older homes or runoff from nearby roads. Silver Spring deals with urban runoff into streams like Sligo Creek, which can carry contaminants. Unlike industrial-heavy areas, our county’s risks stem from biotech, waste management, and aging infrastructure. For example, groundwater contamination from septic leaks or old storage tanks affects wells in suburban spots.

From my cases, I’ve seen how these exposures lead to real suffering, respiratory problems, skin issues, or worse, like cancer links. Businesses aren’t immune; a manufacturing plant might face claims if emissions drift to nearby homes. Maryland law treats these seriously, requiring proof of negligence (like failing to contain a spill) and causation (linking the toxin to your illness). It’s empathetic to victims, but fair to defendants who follow rules.

To illustrate common toxins, here’s a table based on local reports:

| Toxin | Common Sources in Montgomery County | Potential Health Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Dioxins/Furans | Waste incinerators (e.g., Dickerson facility) | Cancer risk, immune issues |

| PFAS (“Forever Chemicals”) | Contaminated water, industrial runoff | Reproductive problems, high cholesterol |

| Asbestos | Older buildings in Bethesda/Silver Spring | Lung diseases like mesothelioma |

| Lead | Paint in pre-1978 homes in Chevy Chase | Neurological damage, especially in kids |

| Benzene | Chemical labs or fuel leaks | Blood disorders, leukemia |

This table draws from environmental data, showing why awareness is key in our towns.

Chapter 2: Common Sources of Toxic Exposure in Bethesda, Chevy Chase, and Silver Spring

Diving deeper, let’s look at where these risks pop up in our specific towns. Bethesda’s biotech and research scene may reveal that labs handling chemicals can lead to accidental exposures for workers or nearby residents if safety lapses occur. I’ve handled claims where lab waste wasn’t properly disposed of, resulting in seepage into groundwater.

In Chevy Chase, it’s more about residential hazards: Older homes might have asbestos insulation or lead pipes, especially near busy roads like Connecticut Avenue, where vehicle emissions contribute to pollution. Stream pollution from erosion carries sediments and chemicals into backyards.

Silver Spring has a mix—urban development means more construction dust with potential toxins, plus proximity to the Dickerson incinerator, which recently exceeded dioxin limits. Industrial sites here are lighter, like small electronics manufacturing, but they handle solvents that could spill. Overall, county-wide issues like well contamination affect 15-25% of private wells with bacterial or chemical contamination, per studies.

For businesses: Manufacturing plants in or near Silver Spring (e.g., electronics assembly) risk volatile organic compounds (VOCs) releases. Industrial ops must comply with EPA rules, but slips happen.

Here’s another table on local hotspots:

| Town | Key Exposure Sources | Examples from Reports |

|---|---|---|

| Bethesda | Biotech labs, construction | Chemical handling at NIH; potential spills |

| Chevy Chase | Residential runoff, old infrastructure | Lead paint; road pollutants into wells |

| Silver Spring | Urban streams, waste proximity | Sligo Creek erosion; incinerator emissions |

These aren’t alarmist—they’re based on county environmental reports and emphasize prevention.

Chapter 3: How Toxic Exposures Affect Residents’ Health and Lives

- Research suggests that prolonged exposure to pollutants like PFAS and dioxins in areas such as Bethesda and Silver Spring may elevate risks for immune system weakening, potentially increasing vulnerability to infections and certain cancers, though individual outcomes vary based on exposure levels and personal health factors.

- Evidence leans toward links between air pollutants, including fine particulates and ozone, and heightened asthma episodes or heart-related issues in denser urban-suburban zones like Silver Spring, with children and the elderly appearing more susceptible.

- Studies indicate that lead exposure in older homes, common in Chevy Chase, could contribute to developmental delays in children, while asbestos in aging buildings raises concerns for long-term lung conditions, emphasizing the need for proactive testing.

- It seems likely that cumulative effects from multiple sources—such as water contaminants and indoor air toxins—exacerbate mental health stresses, including anxiety from health uncertainties, particularly in communities with limited access to resources.

- While not all exposures lead to severe illness, local data highlights disparities, with lower-income areas in Silver Spring showing higher rates of pollution-related health visits, underscoring environmental equity issues.

Overview of Common Health Effects

As a personal injury attorney in Montgomery County, I’ve witnessed how toxins quietly disrupt daily lives. Residents in Bethesda might encounter PFAS in drinking water, linked to hormonal imbalances and reduced immune function, making everyday activities like family outings more challenging due to fatigue or frequent illnesses. In Silver Spring, air quality alerts for ozone can trigger immediate symptoms like coughing or shortness of breath, especially during summer heat waves. Chevy Chase’s older housing stock often harbors lead or asbestos, where even minor renovations could release particles causing skin irritation or long-term worries about cancer risks.

Vulnerable Populations and Disparities

Certain groups bear a heavier burden. Children exposed to lead may face learning difficulties, as seen in cases I’ve handled where school performance dropped noticeably. Elderly residents with pre-existing conditions, common in our suburban towns, report worsened asthma from particulate matter drifting from nearby roads or facilities. Data from Maryland health reports show urban-suburban mixes like ours experience more emergency visits for respiratory issues, with racial and economic disparities amplifying the impact—lower-income neighborhoods in Silver Spring, for instance, report higher asthma rates tied to proximity to pollution sources.

Emotional and Financial Toll

Beyond physical symptoms, the uncertainty breeds stress. Families I’ve represented describe sleepless nights worrying about well contamination leading to gastrointestinal woes, or the financial strain of medical bills. Compensation can help cover treatments, but the emotional weight lingers, affecting work productivity and family dynamics. Proactive steps, like home testing, offer some peace, but broader community action is essential to mitigate these hidden threats.

| Common Toxin | Primary Exposure Route | Short-Term Symptoms | Potential Long-Term Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS | Drinking water, seafood | Nausea, fatigue | Cancer (kidney, testicular), immune suppression, reproductive issues |

| Dioxins | Air emissions from incinerators | Headaches, irritation | Cancer, developmental delays, hormonal disruptions |

| Lead | Paint in older homes, pipes | Abdominal pain, irritability | Neurological damage, learning disabilities in children |

| Asbestos | Building materials in renovations | Coughing, chest tightness | Lung cancer, mesothelioma, asbestosis |

Understanding the Mechanisms of Harm

Toxic exposures operate through various pathways—inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact—leading to a cascade of biological responses. For instance, PFAS, often dubbed “forever chemicals” due to their persistence in the environment and body, bioaccumulate over time. In Bethesda, testing has revealed drinking water levels ranging from 26.94 to 48.35 parts per trillion (ppt) across multiple compounds, surpassing health-based thresholds suggested by experts like those at Harvard, who recommend limits as low as 1 ppt for certain PFAS to minimize risks. These chemicals interfere with endocrine functions, potentially causing reproductive issues such as decreased fertility or complications in pregnancy, and weakening the immune system, which studies suggest may heighten susceptibility to infections like COVID-19 or exacerbate their severity. Chronic exposure has also been associated with elevated cholesterol, liver damage, and cancers including kidney and testicular varieties, as noted in EPA summaries of peer-reviewed research.

Airborne pollutants present another layer of risk. The Dickerson incinerator, a key waste management facility serving Montgomery County, recently exceeded state limits for dioxins and furans by about 83% in one boiler, releasing these highly toxic substances that can cause cancer, reproductive problems, and immunological disorders. While the issue was addressed through repairs, the potential for prolonged undetected emissions raises alarms for residents downwind, including those in Silver Spring and Bethesda. Short-term effects might include throat irritation or headaches, but long-term, dioxins are linked to developmental delays in children and hormonal disruptions, compounding risks in areas already facing urban air challenges.

Lead, prevalent in pre-1978 homes dotting Chevy Chase’s residential neighborhoods, targets the nervous system. Ingestion through chipped paint or contaminated dust can lead to immediate symptoms like abdominal pain or irritability, but the real concern is cumulative: It impairs cognitive development in kids, potentially lowering IQ and causing behavioral issues, as evidenced by Maryland health data showing neurological impacts in exposed populations. Asbestos, found in older building materials across the county, poses inhalation risks during disturbances like renovations. It causes asbestosis—a scarring of the lungs leading to chronic shortness of breath—and increases odds of lung cancer or mesothelioma, a rare but aggressive cancer of the chest lining, with risks amplified by smoking.

Indoor air quality adds to the burden, with mold and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from paints and cleaners contributing to respiratory irritation and allergies. Montgomery County’s Department of Environmental Protection emphasizes that homes can harbor more pollution than outdoor urban air, exacerbating conditions like asthma. Gas stoves, common in many households, release nitrogen dioxide levels exceeding EPA outdoor standards in 63% of tested DC and Montgomery County homes, linking to increased asthma attacks and throat discomfort.

Local Data and Disparities in Health Outcomes

Montgomery County’s health landscape reflects these exposures. The 2025 Community Health Needs Assessment by the Montgomery County Hospital Collaborative identifies heart disease, cancer, mental health issues, and respiratory conditions as leading concerns, often tied to environmental factors. Age-adjusted mortality rates show disparities: Non-Hispanic Black residents face rates 1.2 times higher than White counterparts, with unintentional injuries and infections prominent, potentially aggravated by pollution. In Silver Spring, denser urban settings correlate with higher asthma prevalence; over 60,000 adults county-wide suffer, per Maryland Asthma Control Program data, with particulate matter from traffic and incinerators worsening symptoms like wheezing and reduced lung function.

Bethesda’s proximity to biotech labs and research facilities introduces unique risks, such as potential chemical spills that can cause acute burns or dizziness, while chronic exposures mirror broader countywide trends in cancer risk. Chevy Chase, with its historic homes, sees elevated lead-related concerns, contributing to childhood developmental issues. Climate change amplifies these, with increased heat waves projected to spike 95-plus degree days by 1,400% by 2100 if emissions aren’t curbed, heightening respiratory and cardiovascular strains.

A table summarizing key health data from local sources:

| Health Condition | Prevalence in Montgomery County | Linked Exposures | Disparity Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Over 60,000 adults affected | Air particulates, ozone, NO2 from stoves | Higher in lower-income Silver Spring areas; Black youth at greater risk |

| Cancer (various) | Leading cause of death; kidney/testicular linked to PFAS | PFAS, dioxins, asbestos | Rates 1.2x higher in Black residents; environmental equity gaps |

| Heart Disease | Top mortality cause (97.9/100,000) | Particulates, air pollution | Aggravated in elderly; urban-suburban mix increases visits |

| Developmental Issues | Higher in exposed children | Lead, dioxins | Prevalent in older Chevy Chase homes; affects learning/IQ |

| Immune/ Reproductive | Emerging concerns from PFAS | Water contaminants | Bethesda water levels exceed advisories; potential COVID vulnerability |

Personal and Community Stories

From my practice, stories abound: A Silver Spring family suffered persistent stomach upsets from well contamination, eventually tracing it to nearby runoff; their claim secured funds for filtration and medical care, but the anxiety persisted. In Bethesda, a resident linked chronic fatigue to PFAS-tainted water, highlighting how such exposures erode quality of life. Mental health ties are evident—uncertainty fuels anxiety and depression, with county surveys noting social/environmental factors like pollution as key stressors. Financially, medical costs mount, often hitting underserved communities hardest, where access to testing or clean alternatives is limited.

Broader Implications and Calls for Action

These effects underscore environmental justice: Lower-income and minority areas in Silver Spring face compounded risks from incinerator emissions and urban runoff, per reports on disproportionate pollution burdens. While Maryland lacks strict PFAS regulations, emerging studies urge lower exposure limits to protect against cumulative harms. As an attorney, I advocate for vigilance—regular water testing, air quality monitoring, and legal recourse when negligence occurs. Community efforts, like those in the County’s Climate Action Plan, aim to reduce emissions, but individual actions matter too: Filter water, ventilate homes, and report concerns to DEP.

In essence, toxic exposures in our towns weave a complex web of health challenges, from immediate irritations to lifelong risks, demanding a collective response for healthier lives.

Chapter 4: Challenges for Businesses, Industrial Sites, and Manufacturing Plants

Shifting to the other side, businesses in our towns face tough spots. In Bethesda’s biotech corridor, firms like AstraZeneca handle chemicals but risk claims if protocols fail. Manufacturing plants near Silver Spring (e.g., electronics) face solvent exposures, which may lead to employee lawsuits.

Industrial sites must navigate Maryland’s strict regulations and fines for emissions exceeding limits, as in the incinerator case. Liability can bankrupt small ops if a spill affects residents. Defenses include showing compliance, but juries often side with victims.

- Research suggests that businesses in Montgomery County, such as biotech firms in Bethesda, may face heightened liability risks from chemical exposures if safety protocols lapse, potentially leading to employee or resident claims under Maryland’s negligence standards.

- Evidence leans toward industrial sites, like waste facilities near Silver Spring, encountering regulatory challenges with emissions and stormwater runoff, where exceedances could trigger fines or toxic tort suits, though compliance defenses often mitigate outcomes.

- It seems likely that manufacturing plants handling solvents or metals in areas like Silver Spring contribute to pollution concerns, including PFAS and heavy metals, amplifying health risks and legal exposure, but proactive measures can reduce vulnerabilities.

- Studies indicate that small operations may struggle with the financial burden of litigation or cleanup, while larger entities benefit from insurance and expert defenses, highlighting disparities in managing toxic tort threats.

- While not all operations result in claims, local data points to environmental justice issues in denser areas, underscoring the need for balanced approaches that consider community impacts without assuming universal fault.

Overview of Business Challenges

As Basil M. Al-Qaneh, Esq., I’ve represented both sides in these matters, and it’s clear that businesses in Montgomery County navigate a complex landscape of regulations and potential liabilities. In Bethesda’s biotech hubs, companies like those near NIH handle hazardous substances, increasing the risk of claims if spills or exposures occur. Silver Spring’s manufacturing and industrial zones deal with runoff pollutants, while Chevy Chase’s lighter commercial activities still face occasional issues from construction or older infrastructure.

Key Risks by Sector

Biotech firms often encounter toxic tort risks from antineoplastic drugs or chemicals, leading to health claims like skin issues or reproductive harm. Industrial sites must comply with stormwater permits to avoid fines for exceedances of metal or nutrient limits. Manufacturing plants face challenges with VOCs and heavy metals in emissions, potentially affecting nearby residents.

Legal and Financial Implications

Maryland law requires proving negligence, but juries may favor victims, making defenses like compliance crucial. Costs can escalate with expert witnesses and settlements, but insurance helps proactive companies.

| Sector | Primary Challenges | Potential Liabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Biotech | Chemical handling lapses | Employee exposure suits |

| Industrial | Emission exceedances | Fines and community claims |

| Manufacturing | Runoff pollution | Environmental cleanup orders |

Consult professionals to assess risks—prevention is key.

In my practice as a personal injury attorney in Montgomery County, Maryland, I’ve seen how businesses, industrial sites, and manufacturing plants grapple with the dual pressures of operational demands and potential toxic tort liabilities. These challenges are particularly acute in our key towns: Bethesda’s thriving biotech corridor, Chevy Chase’s residential-adjacent commercial activities, and Silver Spring’s mix of urban manufacturing and waste management proximity. While heavy industry isn’t as dominant here as in other parts of Maryland, the risks from chemical handling, emissions, and runoff are real and can lead to costly lawsuits if not managed carefully. This expanded chapter draws on local regulations, case examples, and environmental data to outline these hurdles, emphasizing that while liabilities exist, strong compliance and defenses often protect responsible operators.

Regulatory Framework and Compliance Burdens

Montgomery County’s environmental regulations create a stringent backdrop for businesses. The county’s Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS), enacted via Bill 16-21, require buildings over 25,000 square feet—including many industrial and manufacturing facilities to meet energy-efficiency thresholds, thereby indirectly impacting pollution control by reducing emissions from operations. Additionally, the Illicit Discharge Ordinance prohibits pollutants from entering waterways, with industrial sites required to monitor stormwater for toxins like heavy metals and nutrients. The Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permit mandates source identification and pollution prevention plans, linking stormwater runoff to specific water quality impacts. For biotech companies in Bethesda, federal guidelines from OSHA and NIOSH on hazardous drugs add layers, requiring controls for exposures that could cause skin rashes, reproductive issues, or cancers.

Non-compliance can result in fines— for instance, the Dickerson incinerator near Silver Spring exceeded dioxin limits by 83%, leading to state-mandated repairs and potential liability if health impacts arise. Smaller manufacturing plants in Silver Spring face disproportionate burdens, as stormwater testing revealed exceedances of copper, lead, and zinc at facilities that handle metals, with average violations by hundreds of percent. PFAS contamination in local water and seafood further complicates matters, with levels in Montgomery County wells exceeding health advisories, potentially stemming from industrial runoff.

Sector-Specific Risks in Key Towns

In Bethesda, biotech firms like AstraZeneca or those near NIH handle antineoplastic drugs and chemicals, posing risks of occupational exposures. A 2015 FDA inspection at NIH’s facility highlighted contamination issues, halting production and underscoring how lapses can lead to tort claims for harm to workers or the community. Studies show these substances can cause infertility or organ toxicity, amplifying liability if protocols fail.

Chevy Chase, with its residential focus, sees fewer direct industrial challenges but risks from nearby construction or older sites with lead/asbestos. Businesses here might face secondary liabilities from runoff affecting wells, as county data indicates 15-25% contamination rates.

Silver Spring’s manufacturing and industrial landscape presents acute pollution challenges. Facilities handling electronics or metals contribute to stormwater laden with VOCs, heavy metals, and PFAS, as seen in reports of toxic releases totaling 94,000 pounds into Maryland waterways in 2020. Proximity to the Dickerson facility exacerbates air and water concerns, with dioxins linked to cancer risks. Environmental justice issues loom, as lower-income areas bear higher pollution burdens.

A table of sector risks based on local data:

| Town/Sector | Common Pollutants | Key Challenges | Example Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bethesda/Biotech | Hazardous drugs, chemicals | Exposure during handling | Worker health claims, contamination halts |

| Chevy Chase/Commercial | Lead, asbestos from infrastructure | Runoff from construction | Well contamination, resident suits |

| Silver Spring/Manufacturing | Heavy metals, PFAS, VOCs | Stormwater exceedances | Fines, community health risks |

| Industrial (County-wide) | Dioxins, nutrients | Emission limits | Regulatory violations, tort liabilities |

Legal Liabilities and Defenses

Under Maryland law, toxic torts require proving negligence—duty, breach, causation, damages. Businesses can be liable as property owners, employers, or manufacturers if exposures cause harm. Punitive damages are rare due to stringent standards shaped by appellate cases. In Montgomery County v. Complete Lawn Care (2019), the county challenged a pesticide ordinance, illustrating how local laws can conflict with state preemption, affecting business operations. Other cases, like Rios v. Montgomery County (2004), highlight tort claims act notices in exposure suits.

Defenses include demonstrating compliance with EPA, MDE, and county regs, or arguing lack of causation via experts. Juries often sympathize with victims, but settlements are common to avoid trials. Small ops risk bankruptcy from spills, while larger firms use insurance.

Mitigation Strategies and Best Practices

Proactive steps include regular audits, employee training, and pollution controls like BSCs for biotech. Businesses should maintain records for defenses, as in asbestos cases where historic data proved crucial. Community engagement addresses equity concerns, especially in Silver Spring.

Another table on mitigation:

| Strategy | Application | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Compliance Audits | Annual reviews of emissions/runoff | Reduces fines, strengthens defenses |

| Training Programs | Hazard handling for workers | Prevents exposures, lowers claims |

| Insurance Coverage | Tailored for toxic torts | Financial protection against suits |

| Tech Investments | Advanced filtration systems | Minimizes pollutants, aids sustainability |

From my experience, vigilant companies rarely face claims—focus on prevention for a safer, more sustainable operation.

Chapter 5: Your Legal Rights: Filing a Claim in Maryland

Under Maryland law, you can file a toxic tort claim if negligence caused your exposure. Statute: Three years from discovery (Courts & Judicial Proceedings §5-101). Prove duty, breach, causation, damages—experts help.

- Research suggests that under Maryland law, residents may pursue toxic tort claims based on negligence, with a three-year statute of limitations typically starting from the date of injury discovery, though exceptions exist for certain cases, such as wrongful death.

- Evidence leans toward requiring proof of four key elements—duty, breach, causation, and damages—to succeed in a claim, often necessitating expert testimony to link exposure to harm.

- Studies indicate that compensation can include economic losses like medical bills and lost wages, non-economic damages for pain and suffering (capped at $890,000 for claims arising after October 1, 2023), and rarely punitive damages if egregious conduct is proven.

- It seems likely that filing occurs in Circuit Court for claims over $30,000 or District Court for smaller amounts, with venue often in the county where the exposure happened, such as Montgomery County’s Rockville courthouse.

- While not all claims succeed, local data highlights the importance of timely action and thorough documentation, underscoring potential defenses such as lack of causation or noncompliance with regulations.

Overview of Legal Rights

As Basil M. Al-Qaneh, Esq., I’ve guided many Montgomery County residents through the maze of toxic tort claims, where proving negligence from exposures in places like Bethesda’s labs or Silver Spring’s streams is key. Maryland law empowers you to seek justice if harmful substances cause injury, but success hinges on solid evidence and timely filing. This chapter breaks down your rights, from claim elements to compensation, drawing on state statutes and real cases to empower everyday folks facing these challenges.

Statute of Limitations: Your Time Window

In Maryland, you generally have three years from discovering your injury to file a toxic tort claim, per Courts and Judicial Proceedings §5-101. This “discovery rule” is crucial for latent illnesses, like cancer from PFAS, where symptoms emerge years later. For wrongful death, it’s three years from death, with a 10-year cap for occupational exposures. Miss this deadline, and courts may bar your case—I’ve seen it happen, so act fast.

Elements of a Toxic Tort Claim

To win, prove negligence: (1) Duty—the defendant owed you reasonable care, like safely handling chemicals; (2) Breach—they failed, e.g., improper disposal; (3) Causation—link exposure to your harm via experts; (4) Damages—actual losses suffered. In Montgomery County, where biotech thrives, claims often involve proving exposure pathways, as in lead paint cases where circumstantial evidence suffices if “reasonably probable.”

Types of Compensation Available

Recover economic damages (medical costs, lost income) without cap, non-economic (pain, suffering) capped at $890,000 for post-2023 claims, and punitive if conduct was egregious—rare in toxics. In my cases, settlements often cover medical treatment and lost wages, but juries award more for severe impacts.

Where and How to File Your Claim

For claims over $30,000, file in Montgomery County Circuit Court (Rockville); under $5,000, District Court exclusive; $5,000-$30,000, either. Against government? Follow Tort Claims Act: notify within one year, cap at $400,000. Start with a complaint detailing facts and demands.

Role of Experts in Proving Your Case

Experts are vital: toxicologists link exposure to illness, doctors quantify harm. In Rowhouses v. Smith, circumstantial evidence sufficed in the absence of direct proof.

Common Defenses and How to Overcome Them

Defendants argue no causation, compliance, or contributory negligence (barring recovery if you’re 1% at fault). Strong evidence counters this.

Real-World Case Examples

In Pinner v. Pinner (2020), jurisdiction over exposures was key. Rowhouses eased causation proof. ExxonMobil v. Ford (2012) slashed damages, highlighting caps.

| Step | Description | Key Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Consult Attorney | Assess viability | Free initial meetings common |

| 2. Gather Evidence | Medical records, exposure proof | Document symptoms early |

| 3. File Claim | Within 3 years | Circuit Court for >$30K |

| 4. Discovery | Exchange info | Experts crucial |

| 5. Settlement/Trial | Negotiate or litigate | Most settle pre-trial |

| Damage Type | Examples | Caps/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | Medical bills, lost wages | No cap |

| Non-Economic | Pain, suffering | $890K for post-2023 |

| Punitive | Egregious conduct | Rare, no cap but strict standards |

Statute of Limitations in Depth

The three-year clock starts upon “discovery”—when you knew or should have known of the injury and its cause. For hidden harms like dioxin exposure, this extends time, but courts scrutinize “reasonable diligence.” Wrongful death: three years from death, or 10 from occupational exposure discovery. Tolling for minors until 18 in some cases. Against state entities? One-year notice under Tort Claims Act.

Proving the Elements

Duty often arises from foreseeable harm, like labs owing safe disposal. Breach: failing standards, e.g., incinerator exceedances. Causation: “Reasonably probable” via circumstantial evidence, as in lead cases. Damages: Quantifiable losses.

Compensation Breakdown

Economic: Unlimited, covering future care projections. Non-economic: Capped, escalating annually. Punitive: Requires “actual malice,” upheld rarely in toxics. Medical monitoring possible for at-risk.

Filing Logistics

Venue: Where exposure occurred or defendant resides—often Rockville Circuit for Montgomery. Complaint: Detail facts, theories (negligence, strict liability). Fees: Vary by court.

Experts’ Critical Role

Daubert-like standards ensure reliability; pediatricians, toxicologists testify on pathways.

Anticipating Defenses

Contributory negligence absolute bar; public duty for governments; statutes of repose. Overcome with evidence.

Notable Maryland Cases

Pinner: Jurisdiction in exposures. Rowhouses: Circumstantial causation. ExxonMobil: Reduced damages in contamination. Levitas: Expert on pathways.

These insights, from statutes to verdicts, equip you to pursue justice confidently.

Chapter 6: Prevention Tips and Resources for a Safer Community

- Research suggests that residents in Montgomery County can reduce toxic exposure risks by regularly testing private wells for contaminants like PFAS and lead, maintaining proper ventilation in homes, and using non-hazardous cleaning alternatives, potentially lowering health impacts from common household pollutants.

- Evidence leans toward businesses implementing comprehensive safety programs, including regular audits and employee training on chemical handling, to minimize liabilities and prevent incidents that could lead to toxic tort claims.

- Studies indicate that community reporting of pollution via channels like Montgomery County’s 311 service plays a key role in early detection and mitigation of environmental hazards, fostering safer neighborhoods.

- It seems likely that participating in local advocacy groups, such as Bethesda Green or Nature Forward, empowers residents and businesses to advocate for stronger environmental policies, though individual actions remain crucial for immediate risk reduction.

- While not all preventive measures guarantee complete safety, local data highlights the effectiveness of proper hazardous waste disposal programs in reducing groundwater contamination, underscoring the value of community-wide efforts.

Essential Prevention Strategies for Residents

Simple steps can make a big difference in avoiding toxic exposures at home. Start by testing your well water annually if you’re on private supply—Montgomery County offers resources through the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) for guidance. Use eco-friendly cleaners to cut down on volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and ensure good ventilation during painting or remodeling to minimize inhalation risks. Report any suspected pollution, like unusual odors or spills, promptly to 311 for quick response.

Business Best Practices to Mitigate Risks

For companies in areas like Bethesda’s biotech sector or Silver Spring’s manufacturing, focus on compliance with Maryland’s environmental regs. Conduct regular site audits, provide protective gear, and train staff on safe chemical handling. Implementing stormwater management plans can prevent runoff pollution, reducing potential claims from neighbors or employees.

Key Local Resources

Tap into Montgomery County’s DEP for water-quality testing kits and air-pollution reporting. Organizations like One Montgomery Green offer education on sustainability, while the Sierra Club provides advocacy tools. For hazardous waste, use the county’s collection programs to dispose safely.

In my years as a personal injury attorney in Montgomery County, Maryland, I’ve learned that prevention is the most powerful tool against toxic tort issues. While we’ve covered the risks and legal paths in previous chapters, Chapter 6 shifts focus to actionable steps and resources that empower residents, businesses, and communities in Bethesda, Chevy Chase, and Silver Spring to build a safer environment. Drawing on local environmental reports, health guidelines, and advocacy insights, this expanded chapter provides practical data-backed tips, emphasizing that while exposures can’t always be eliminated, proactive measures significantly reduce risks and liabilities.

Building a Prevention Mindset

Prevention starts with awareness. Montgomery County’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) stresses that everyday actions—like proper chemical storage and waste disposal—can prevent the subtle build-up of toxins that lead to health claims. For residents, this means avoiding hazardous products where possible; for businesses, it involves robust safety protocols to sidestep tort litigation. Maryland’s environmental framework, including the Water Quality Ordinance, supports these efforts by prohibiting unauthorized pollutant discharges and enforcing compliance through fines and corrections.

Resident-Focused Prevention Tips

Homeowners in our suburban towns face risks from aging infrastructure and urban runoff. Annual well testing is crucial, as 15-25% of private wells show contamination per county studies. Use non-toxic alternatives for cleaning: Baking soda and vinegar replace harsh chemicals, reducing VOC exposure that causes headaches and respiratory issues. Ventilate during renovations to avoid inhaling paint or solvent fumes, and fix leaks promptly to prevent mold. For lead in older Chevy Chase homes, test paint and pipes, especially if children are present.

In Silver Spring, monitor air quality via DEP’s real-time data and report emissions from nearby facilities. Participate in stream cleanups organized by groups like Friends of Sligo Creek to curb water pollution. Bethesda residents near labs should advocate for safe waste disposal through community forums.

A table of resident tips:

| Tip Category | Specific Actions | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Water Safety | Test wells yearly; filter if needed | Reduces PFAS/lead risks |

| Air Quality | Use low-VOC products; ventilate | Lowers respiratory issues |

| Waste Handling | Proper disposal via county programs | Prevents groundwater pollution |

| Home Maintenance | Fix leaks; test for mold/lead | Avoids chronic exposures |

Business and Industrial Prevention Strategies

Manufacturing plants and industrial sites must prioritize compliance to avoid claims. Develop safety programs with audits, training, and protective gear, as recommended by legal experts. In Silver Spring, stormwater permits require pollution-prevention plans to address metals and VOCs. Biotech firms in Bethesda should follow OSHA guidelines for hazardous drugs, using enclosed handling to prevent spills.

Insurance reviews and vendor contracts can mitigate financial risks. Community engagement, like partnering with local greens, builds goodwill and addresses equity in polluted areas.

Table of business strategies:

| Sector | Key Measures | Potential Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | Stormwater controls; audits | Fewer exceedances, lower fines |

| Biotech | Training; enclosed systems | Reduced worker exposures |

| Industrial | Emission monitoring | Compliance with NAAQS |

| All | Insurance; community outreach | Mitigated liabilities |

Community Resources and Advocacy

Montgomery DEP is central: Call 240-777-0311 for pollution reports or 240-777-6560 for hazardous waste. MDE handles state-level issues like air complaints at mdeair.complaints@maryland.gov.

Local groups: Bethesda Green fosters sustainability initiatives. Nature Forward (Chevy Chase) advocates for habitats. One Montgomery Green educates on green living. Sierra Club and Conservation Montgomery push policies.

Table of resources:

| Organization | Focus Area | Contact Info |

|---|---|---|

| Montgomery DEP | Pollution reporting, testing | 240-777-0311; montgomerycountymd.gov/dep |

| MDE | State regs, complaints | mde.maryland.gov; 410-537-3000 |

| Bethesda Green | Sustainability education | bethesdagreen.org |

| Nature Forward | Habitat protection | natureforward.org; 301-652-9188 |

| One Montgomery Green | Community outreach | onemontgomerygreen.org |

| Sierra Club MD | Advocacy | sierraclub.org/maryland |

Toward a Safer Future

Collective action amplifies impact. Grants like the Clean Water Montgomery fund restoration. By integrating these tips and resources, we can reduce exposures, echoing Maryland’s commitment to environmental health.

Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Maryland, Virginia, & DC attorney.)

References

- Maryland Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article §5-101 (Statute of Limitations for Personal Injury Claims).

- Maryland Environment Article §9-301 et seq. (Water Pollution Control).

- Case: Randy R. Pinner v. Mona H. Pinner (2020) – Involved a toxic tort action filed in Maryland, illustrating jurisdiction over out-of-state exposures.

- Case: Mona H. Pinner v. Randy R. Pinner (2019) – Highlighted filing of toxic tort suits in MD courts for asbestos-related injuries.

- Maryland Department of the Environment Reports on Dickerson Incinerator Emissions (2025) – Documented dioxin exceedances.

- University of Maryland Well Water Study (various counties, including Montgomery) – Found 15-25% contamination rates.

Key Citations

Maryland Environmental and Groundwater Contamination Lawyers

Baltimore Toxic Torts & Toxic Exposure Lawyer

Burning or burying? The safer path for Montgomery County’s waste

Waste incinerator emitted an excess of toxic pollutants

Dickerson incinerator operator violated allowable levels

Burn it or bury it: Montgomery County at a waste management crossroads

More PFAS Found in Maryland Water and Seafood – PEER.org

Waste incinerator emitted an excess of toxic pollutants, test shows – The Baltimore Banner

Indoor Air Quality, Montgomery County, MD Government

Your Guide to Air Quality – My Green Montgomery