Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

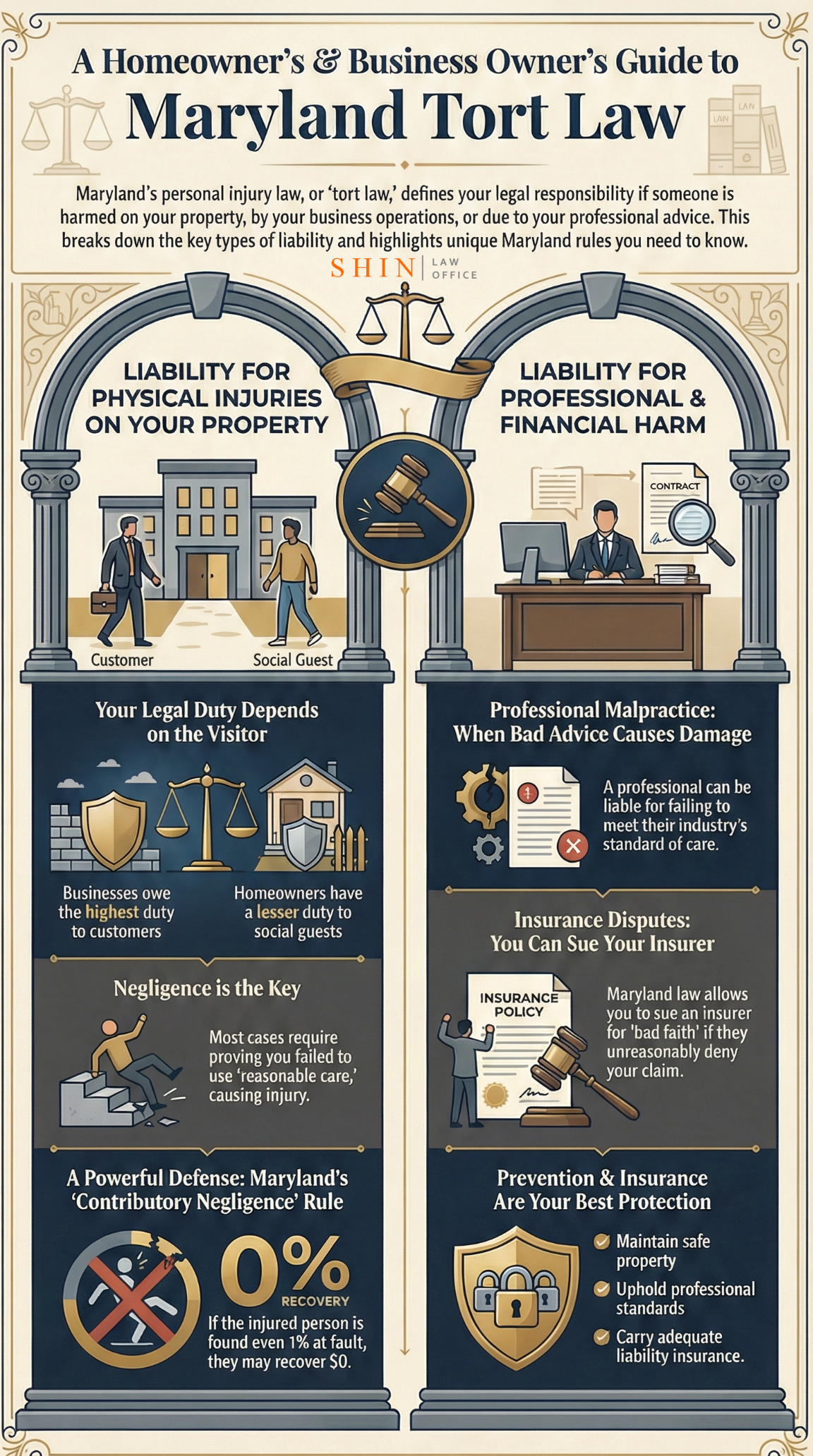

Lawsuits over accidents and injuries can happen to anyone – even homeowners and business owners here in Montgomery County. Everyday scenarios like a slip-and-fall at your home or a client suing for negligent professional advice are common examples of tort cases. As an attorney practicing in this community, I want to demystify how Maryland’s personal injury law works in these situations. In this blog, I’ll explain in plain English the key concepts – from a property owner’s duty to keep visitors safe, to a professional’s liability for bad advice, to insurance disputes when claims are denied – all with a local Montgomery County perspective. The goal is to give homeowners and business owners a clear understanding of their rights and risks under Maryland law, including unique rules like our “contributory negligence” doctrine (where if you are even 1% at fault, you might recover nothing). Let’s dive in, chapter by chapter, so you know what to expect and how to protect yourself.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction to Tort and Personal Injury Lawsuits

- Chapter 2: Premises Liability – Slip-and-Fall Injuries at Home

- Chapter 3: Premises Liability – Slip-and-Fall Injuries at Businesses

- Chapter 4: Professional Negligence and Malpractice

- Chapter 5: Insurance Litigation – Claim Denials and Coverage Disputes

- Chapter 6: Conclusion – Navigating the System and Protecting Your Rights

- References

Chapter 1: Introduction to Tort and Personal Injury Lawsuits

What is a tort? A tort is a wrongful act that causes harm to someone, for which the injured person can seek compensation in a civil lawsuit. “Personal injury” generally means an injury to your body, mind, or emotions. These cases are separate from any criminal charges – they’re about the injured person (plaintiff) suing the responsible party (defendant) for money damages. Common examples of tort cases include car accidents, slip-and-fall accidents, and medical malpractice. What many people don’t realize is that you don’t have to be a big company or a habitual wrongdoer to be involved in a tort case. Everyday Montgomery County residents and businesses can find themselves on either side of a lawsuit when accidents happen.

Negligence is the key: Most personal injury cases are based on negligence – essentially, someone’s failure to take reasonable care, resulting in harm to another. To win a negligence case in Maryland, the injured person must prove four elements: (1) the defendant owed a duty to the plaintiff, (2) the defendant breached that duty by not acting as a reasonably careful person would, (3) the breach caused an injury, and (4) the plaintiff suffered damages (actual harm). In plain terms, you have to show that the other person had an obligation to be careful, they failed at that, and that failure directly led to your injury. For example, drivers owe a duty to obey traffic laws and drive safely; if a driver runs a red light (breach of duty) and hits another car, causing injury, that driver can be liable for negligence.

Real-world scenarios: You might be thinking this only applies to car crashes or big lawsuits, but it can be much closer to home. Imagine you invite a friend over to your house in Gaithersburg and they trip on a broken step on your porch, breaking their ankle. Or perhaps you run a small business in Bethesda, and a customer slips on a wet floor in your store. In both cases, you could be facing a personal injury claim alleging negligence. Even professionals like lawyers or accountants can be sued if their mistakes cause a client financial harm (more on that in Chapter 4). And let’s not forget insurance – if your insurer refuses to cover an accident or pay a claim you believe is valid, that dispute can end up in court (Chapter 5 will cover insurance litigation).

Montgomery County context: As a lawyer who lives and works here, I see these cases filed regularly in our local courts. The Montgomery County Circuit Court in Rockville handles many personal injury lawsuits each year, from everyday slip-and-fall cases to complex malpractice suits. The community we live in – with bustling commercial areas in Silver Spring and Rockville, suburban neighborhoods, and busy roads – naturally experiences its share of accidents and disputes. Knowing a bit about Maryland law helps you understand your potential exposure. For instance, Maryland has a 3-year statute of limitations for most personal injury lawsuits (meaning you generally must file suit within three years of the injury). Also, Maryland follows something called “contributory negligence” (one of only a few states that do) – this rule says if the injured person was even slightly at fault for their own injury, they can be barred from any recovery. That’s a harsh rule (unlike the comparative negligence in most states, where you can still recover a reduced amount if you were partially at fault). The Maryland Court of Appeals (now called the Supreme Court of Maryland) has upheld this contributory negligence rule in cases like Coleman v. Soccer Ass’n of Columbia (2013), leaving any change to the legislature.

Insurance is your safety net: One comforting fact for homeowners and businesses is that insurance coverage often comes into play. If someone sues you because they got hurt on your property or due to your mistake, typically your liability insurance (homeowners insurance, commercial general liability policy, etc.) will defend the claim and pay any settlement or judgment up to the policy limits. Of course, as we’ll discuss later, insurers don’t always agree to pay – and that’s when legal disputes with the insurer arise. But generally, carrying adequate insurance is critical. It protects you and provides an attorney (hired by the insurer) to defend you in court. I always advise folks in Montgomery County communities like Bethesda, Rockville, and Germantown to review their insurance policies and make sure they have coverage for common risks (like injuries on their property or professional liability insurance if you provide services).

In summary, tort litigation isn’t something that only happens to “other people.” It’s part of life – accidents happen, misunderstandings with insurers happen, and sometimes lawsuits follow. The following chapters will break down specific areas (premises liability, professional malpractice, insurance disputes) in a way that I hope will be clear and useful, even if you’re not a lawyer.

Chapter 2: Premises Liability: Slip-and-Fall Injuries at Home

If you own a home in Montgomery County (perhaps in a neighborhood of Rockville, Bethesda, or Silver Spring), you probably take pride in making it a safe place for your family and guests. But what if someone still gets hurt on your property? Say a neighbor or delivery person slips on your icy driveway, or a friend’s child trips over a loose floorboard. You might be surprised (and a little scared) to learn you could be held legally responsible for their injuries under Maryland’s premises liability law.

Your duty as a homeowner: In Maryland, the duty you owe to someone on your property depends on their legal status – basically, why they are on your property. There are three main categories: invitees, licensees, and trespassers. An invitee is someone you invite for a mutual benefit (think of a plumber you hired or if you were running a yard sale open to the public). A licensee by invitation is typically a social guest – for example, a friend coming over for dinner. A trespasser is someone on your property without permission. The law assigns different duties of care to each:

- Invitees (highest duty): You must take active steps to ensure safety for invitees. That means regularly inspecting your property for hazards, fixing dangerous conditions, and warning them of any risks that aren’t obvious. If you hire a contractor to fix your cable and you know your front porch step is broken, you should fix it or at least warn them, and ideally put up a sign or barrier until it’s repaired. If you fail to do so and they get hurt, you could be liable.

- Licensees (social guests): For licensees, you must warn them of known dangers on your property and either fix those dangers or refrain from wantonly harming your guests. However, you don’t have to inspect for hidden problems before a guest arrives. In other words, if you know something could be hazardous (say, that rickety railing on your deck or a slippery spot on the kitchen floor), you should tell your guests or remedy it. But if there was a hidden bee’s nest in your backyard that you weren’t aware of, and a visitor gets stung and injured, you might not be held liable because you had no knowledge of that danger despite reasonable care.

- Trespassers (lowest duty): Generally, you owe no duty to a trespasser except not to willfully or wantonly injure them. You can’t set traps or intentionally harm someone, even if they’re on your land, without permission. (There are some nuances if, for example, young children trespass – the “attractive nuisance” doctrine – but that’s beyond our scope here).

So, if you’re a homeowner in Montgomery County and you invite friends over for a BBQ, you essentially are dealing with licensees by invitation. You should ensure any known hazards are addressed or at least alert your guests (“Watch your step on the patio, one of the stones is loose”). If Uncle Joe wanders off into your tool shed (where he wasn’t invited) and injures himself, your responsibility might be less because he possibly became a trespasser in that scenario. These distinctions can actually make or break a case – the law is less forgiving when an invitee (like a paying customer) is injured than when a social guest or trespasser is injured.

A typical “Caution: Wet Floor” sign – these warnings are crucial. As a property owner, you should alert visitors to known hazards (like a wet floor) to avoid liability.

Slip-and-fall scenarios at home: One of the most common types of home accidents that lead to lawsuits is the classic “slip-and-fall.” Perhaps a friend slips on a wet kitchen floor or trips over a loose rug. In evaluating your liability, courts will look at questions like: Did you know about the dangerous condition? Should you have known about it? Did you warn your guest? For instance, if you mopped the floor and forgot to tell your guest to be careful (and they slip), you had actual knowledge of the hazard and failed to warn – that could be negligence on your part. On the other hand, if a glass of water was spilled by another guest just moments before and you didn’t realize it yet, you might argue you had no opportunity to discover or fix the hazard.

Maryland case law emphasizes the importance of the owner’s knowledge. In a well-known slip-and-fall case (which actually involved a store but the principle applies to homeowners too), the court found the defendant not liable because the injured person “failed to provide any evidence that the defendant had knowledge of the [hazard] prior to her injuries.” In plain English, you usually can’t be held liable for a hazard you had no reasonable way to know about in time to prevent the injury. The injured person must show that there was a dangerous condition and that you, as the owner, either knew or should have known about it and failed to do something. If the hazard just occurred (like that freshly spilled drink), the law might side with the homeowner.

Defenses you might have: If you do get sued by an injured visitor, you are not without defenses. Maryland’s contributory negligence rule (mentioned earlier) can be a powerful defense – if you can show the plaintiff (your guest) was even a little bit responsible for their own injury, they lose the case. For example, maybe your friend was running down your hallway in high heels despite you telling everyone to be careful, or they ignored a clear warning sign you posted. If a jury finds the injured party was even 1% negligent themselves, they recover $0 under contributory negligence. Another defense is assumption of risk: if the person knew of a danger and voluntarily exposed themselves to it, they can’t blame you. For instance, if you told your friend, “Don’t go onto the old deck, it’s not safe,” and they did so anyway and got hurt, you’d argue they assumed the risk.

Now, keep in mind these defenses and rules often lead to pretty tough outcomes, which is why many homeowner cases get settled out of court if there’s any doubt. It’s also why having homeowner’s insurance is so important. In most cases, if a guest is injured and makes a claim, your insurance will step in. Typically, the homeowner’s insurance company will assign an adjuster and a lawyer to handle the claim, investigate what happened, and if needed, defend you in a lawsuit. They might decide to settle (pay the injured person) if it’s clear you were at fault, or fight the case if they think you were not negligent or the claim is questionable.

Example: Let me give a hypothetical scenario that’s all too common in winter: You live in Silver Spring, and after a snowstorm, you shovel your driveway but miss a patch of ice on the front steps. Your neighbor comes by to drop off some cookies (so she’s a licensee/social guest). She slips on the icy step and injures her back. She ends up with medical bills and can’t work for a week. In this scenario, could you be liable? Possibly yes, because as a homeowner, you had a duty to exercise reasonable care to make areas safe for expected visitors. You knew or should have known that the steps could be icy after the snow. If you didn’t salt or fully clear the steps, a court could find you breached your duty. Your neighbor would still need to prove your breach caused her injury (which, in this case, is straightforward: she slipped on the hazard). If she hires a lawyer, they might file a claim with your homeowner’s insurer or sue you in the Montgomery County Circuit Court. Your best defense might be contributory negligence (“she wasn’t holding the handrail or wasn’t looking where she stepped”), but that can be a tough sell unless there’s clear evidence. More likely, your insurance would negotiate and perhaps settle the claim, paying her medical bills and maybe something for pain and suffering, rather than risk a trial where you might be found negligent.

Key takeaway: As a homeowner, you should always repair known hazards promptly and warn guests of any dangers. It not only shows good hospitality but also protects you legally. Most importantly, carry liability insurance – it’s usually part of your homeowner’s policy. In Montgomery County, where social gatherings are common, and winter brings ice, etc., these precautions are vital. Should an accident happen, remember that the injured person has to prove you were negligent and that this negligence led to their injury. If you truly did your best to maintain a safe home, you have a strong position. And if you are sued, involve your insurance company and consider consulting an attorney. The legal standards (like what constitutes “reasonable care” or whether the guest was partly at fault) can be complex, but that’s what lawyers and insurance adjusters deal with every day.

Next, we’ll move from the home to the business premises, where the property owner’s responsibilities are even higher in many ways.

Chapter 3: Premises Liability – Slip-and-Fall Injuries at Businesses

Owning or operating a business in Montgomery County – whether it’s a restaurant in Bethesda, a retail shop in Wheaton, or an office in Rockville – comes with many responsibilities. One that sometimes gets overlooked until an accident happens is the duty to keep the premises safe for customers and visitors. If someone slips, trips, or is otherwise injured at your business, you could face a personal injury claim under the same principle of premises liability, but the expectations of care are higher than for private homeowners.

The highest duty: invitees. Customers or clients who come onto a business property are typically classified as invitees (they are there for the business’s benefit, e.g., to shop or do business). Maryland law imposes the “highest duty of care” on property owners toward invitees. What does that mean in practice? As a business owner, you must actively inspect and maintain your property to discover hazards and fix them promptly. You also must warn invitees of any dangers that aren’t obvious. Essentially, you’re expected to be vigilant: have protocols for regular cleaning, safety inspections, repair of any unsafe conditions, and clear signage for any temporary hazards.

For example, think of a grocery store in Germantown. The store should have employees periodically walk the aisles looking for spills or obstacles. If a jar of sauce falls and shatters on the floor, the store should cordon off the area or put up a “Wet Floor” sign and clean it as soon as possible. If they ignore it and a shopper slips, the store will likely be liable for negligence because it failed to meet its duty. In fact, failing to clean up known spills or to post warning signs is a classic scenario that can lead to a store’s liability. One Maryland case noted that a store could be liable if its employees knew of a spill and didn’t clean it or warn customers – that’s a clear breach of duty.

What if the business didn’t know of the hazard? An important aspect in these cases is knowledge (actual or constructive) of the dangerous condition. If a customer slipped on something, to hold the business liable, the injured customer usually must show the business knew or should have known about the hazard in time to do something about it. Maryland courts have reinforced this idea. For instance, in Maans v. Giant of Maryland, LLC, a shopper fell on a wet floor in a grocery store. The court ruled in favor of the store because the customer “failed to provide evidence that the store had knowledge of the wet floor prior to her fall”. There was no proof of how long the spill had been there or that any employee had seen it. The lesson: a business is not an absolute insurer of safety – the plaintiff must prove the store was negligent, not just that an injury happened. If a hazard appeared moments before an accident and no employee could reasonably have known, the business might escape liability.

However, businesses can’t play ostrich. They are expected to take reasonable measures to discover hazards. So even without direct evidence that “Manager Joe saw the spill and ignored it,” a customer can sometimes show constructive notice – e.g., the spill was on the floor for 20 minutes and employees should have discovered it if they were properly monitoring. If the business had poor inspection routines, that can be negligence even if they didn’t actually know of the specific spill. In one Maryland decision, the court suggested that if there’s no evidence of how long a hazard existed, the case might fail (like in Maans). But if the evidence shows the hazard was present long enough that it should have been found during regular checks, then the plaintiff can argue that the store breached its duty of care.

Common business hazards: Some typical causes of injuries in commercial settings include wet or oily floors, uneven pavement or torn carpeting, poor lighting, cluttered walkways, or failing to remove snow/ice from entrances. Montgomery County has commercial hubs with heavy foot traffic, so something as simple as a spilled drink in a busy Bethesda cafe can be a time bomb if not addressed. Another example: in winter, businesses are expected to clear snow and ice from their parking lots and sidewalks within a reasonable time after a storm. If you own a shop in Rockville and leave ice on your steps all day, a patron who slips could have a strong claim that you breached your duty by not tending to an obvious hazard.

Employee negligence becomes your negligence: Under the doctrine of respondeat superior, a business is responsible for the negligent acts of its employees while they’re performing their duties. So if your store clerk knew of a spill and chose to take a smoke break instead of cleaning it, you (the business) are on the hook for that negligence. It’s crucial to train your staff on safety protocols, e.g., immediately placing a caution sign, cleaning hazards, reporting and fixing maintenance issues, etc. Jurors in these cases often hear evidence about the business’s practices. A company with good safety policies that were followed might fend off a claim by showing they did all that was reasonable. Conversely, if the injured person’s attorney shows the business had no regular inspection routine or ignored prior complaints of the dangerous condition, that can greatly sway a case in the plaintiff’s favor.

Maryland’s contributory negligence in business cases: Just like for homeowners, a business can invoke contributory negligence as a defense. Perhaps the customer was not paying attention (say, looking at their phone) and walked right into an obvious hazard that any reasonable person would have seen (like a big orange cone and they still slipped near it). If a jury agrees the customer was even slightly negligent themselves, that bars recovery. However, in reality, businesses typically have a harder time shifting blame to customers unless there’s clear evidence of the patron’s foolish behavior. Businesses invite the public in, so they are expected to anticipate less-than-perfect behavior (we all know some shoppers push carts around without looking – stores still must try to keep aisles safe for everyone). Another defense is that the hazard was “open and obvious.” For example, if there’s a large, bright-yellow wet floor sign and the customer saw it but proceeded anyway, a court might say the danger was obvious, and the business may not be liable (or again, that the customer assumed the risk by proceeding).

Insurance and handling claims: If someone is injured at your business, usually your commercial general liability (CGL) insurance will handle the claim. As a business owner in Montgomery County, you likely have this insurance (often required for leases or by law). The process is similar to homeowners’ claims: the injured party might file an incident report or send a letter, your insurer investigates, and they may settle or defend the claim. Many slip-and-fall cases never reach trial because businesses (or rather their insurers) often settle if the evidence is against them. Trials are risky, and juries can be sympathetic to injured customers, awarding damages for medical bills, lost wages, and pain and suffering. On the flip side, if the business (through its lawyers) believes they did nothing wrong or that the plaintiff is exaggerating, they might deny the claim and fight it in court. Montgomery County juries can be somewhat conservative on injury awards, but it really depends on the facts of the case.

Local example: Picture a Rockville supermarket on a rainy day. People track in water, so the floor by the entrance gets slick. A prudent store manager will have mats out, wet-floor caution signs, and maybe an employee periodically mopping or warning customers. If those precautions are taken and a customer still slips, the store has a strong argument that it exercised reasonable care. But if none of that was done and someone falls, it’s likely a breach of duty. In fact, one case in Maryland held that failure to post a warning sign for a known wet floor could be evidence of negligence.

To tie it together, premises liability for businesses is about vigilance and prevention. As I often counsel small business clients, make safety a routine. A lawsuit can be costly (and bad for reputation). It’s far cheaper to fix that broken step, install proper lighting in the hallway, or retrain staff to clean spills immediately than to pay for someone’s injury and legal fees later. And always notify your insurer quickly if an accident occurs – delaying or trying to handle it quietly can backfire if the claim later grows into a lawsuit.

In the next chapter, we move away from physical accidents to another realm of liability that can catch people off guard: professional malpractice, where the “injury” might be a financial loss or a legal setback caused by someone you trusted for expert advice.

Chapter 4: Professional Negligence and Malpractice

Not all injuries are physical. Sometimes, the harm is financial or legal – for example, you lose a big chunk of money or a legal right because a professional you hired made a serious mistake. In such cases, you may be dealing with professional negligence, commonly known as malpractice. As an attorney, I’m particularly attuned to legal malpractice issues, but the concept extends to many professions: doctors, accountants, architects, real estate agents, and so on. Here in Montgomery County, we have many professionals and service providers. What happens if one of them negligently advises or represents someone and causes harm? Conversely, what if you are a professional (say, a lawyer in Rockville or a financial advisor in Bethesda) and a client accuses you of messing up? Let’s break down how these cases work under Maryland law.

What counts as malpractice? Generally, professional malpractice is when a professional fails to perform their duties to the standard of care expected of their profession, resulting in harm to their client. For example, legal malpractice might occur if a lawyer misses a critical filing deadline and their client’s case is thrown out as a result. Medical malpractice could be a doctor misdiagnosing an illness due to not following proper procedures, causing the patient injury. Accountant malpractice could be a CPA’s math error leading to a client’s massive tax penalty. The key is the concept of duty and breach: the professional owed a duty of care (by virtue of the professional relationship) and breached that duty by acting below the industry standard.

Maryland law, like most states, requires a few elements for a malpractice claim. In the context of legal malpractice, our courts have said the client must prove (1) there was an attorney-client relationship (duty), (2) the attorney breached the applicable standard of care (negligence), and (3) that breach proximately caused an injury (typically a financial loss) to the client. So, essentially, “you were my lawyer, you handled things negligently, and I was harmed as a result.” Other professional cases follow a similar structure – e.g., a doctor-patient relationship, a breach of the medical standard of care, or causing injury.

One unique challenge in legal malpractice cases is proving a “case within a case.” To win, the client often has to prove not only that the lawyer messed up, but that if the lawyer hadn’t messed up, the outcome would have been better for the client. In other words, you have to prove two things: your lawyer was negligent and that their negligence cost you a victory or a benefit in the underlying matter. For instance, if your lawyer failed to file a lawsuit before the statute of limitations and your case got dismissed, you’d need to show that the underlying case was a winner (had the lawyer filed in time, you likely would have won or gotten a settlement). This can be complicated and often requires expert testimony – you might need another attorney to serve as an expert witness to testify about what a competent lawyer should have done and to evaluate the merits of the underlying case.

Maryland’s privity rule – who can sue for malpractice: Maryland generally follows a strict privity rule for legal malpractice, meaning only the client (or someone directly in privity of contract with the professional) can sue for negligence. Our state’s highest court reaffirmed this in a 2024 case, Bennett v. Gentile. In that case, a woman tried to sue her mother’s estate planning attorney, claiming negligence in drafting a trust (and she wasn’t the direct client, her mother was). The Maryland Supreme Court (formerly Court of Appeals) declined to expand liability to non-clients, sticking with the rule that third parties usually cannot sue someone else’s lawyer for malpractice. There is a narrow exception: if the client’s clear intent was to benefit a third party (common example: a will drafting intended to benefit an heir), then that third-party beneficiary might have a claim. But those are rare and hard to prove. The takeaway is, if you’re the harmed party but not the direct client, Maryland courts will likely not allow a malpractice suit. This concept might apply similarly to other professions – typically, you need to be the one who had the professional relationship. (For instance, if you rely on someone else’s accountant’s statement and lose money, you often can’t sue the accountant for negligence unless certain conditions are met.)

Statute of limitations and discovery: Professional malpractice cases often involve a discovery rule. Maryland’s statute of limitations for civil cases is generally 3 years, but in many malpractice situations, you might not know right away that the professional messed up. Maryland follows a “discovery” rule, meaning the clock starts when you knew or reasonably should have known of the wrongdoing. For example, if your lawyer made an error in 2022 but you only discovered it when a judge dismissed your case in 2024, the three-year clock might start in 2024 when you learned of the error. However, these timing issues can be tricky; if you wait too long after suspecting something’s wrong, you could be barred. In legal malpractice, often the client realizes the issue either when a case is lost or when a new lawyer reviews the file and informs them of the mistake. Maryland, being a “notice” state, means that as soon as you have notice of possible malpractice, the clock is ticking.

Expert witnesses and proof: In professional negligence cases, you almost always need an expert witness to establish what the standard of care was and how it was breached. For instance, in a legal malpractice trial, both sides might bring in experienced attorneys as experts – one to say “No reasonable attorney would have done what the defendant did,” and the other to possibly argue the opposite. In medical cases, you need a doctor to testify about what a competent practitioner would have done under the circumstances. Maryland law actually requires a Certificate of Qualified Expert early in a medical malpractice case – essentially a doctor signing off that the claim has merit.

Real-life example (legal malpractice): Imagine a scenario in Montgomery County: A small business owner in Gaithersburg hires an attorney to file a lawsuit over a contract dispute. The attorney misses the filing deadline (perhaps mis-calendared the date), and the case gets dismissed as time-barred. The business owner loses the chance to recover $100,000. Here, the business owner can sue the attorney for malpractice. In the lawsuit, the owner will have to show the attorney had a duty (easy – there was an attorney-client relationship), the attorney breached the duty by failing to act as a reasonably careful lawyer (missing a clear deadline is pretty clearly a breach of the standard of care), and this caused damage – the lost $100,000 claim. The tricky part is proving that the underlying claim was worth $100,000 and was winnable. Essentially, the owner now has to prove that original contract case within the malpractice case to show the value of what was lost. If the owner would likely have lost that contract case anyway (even if timely filed), then the malpractice claim fails because the negligence didn’t cause a recoverable loss. So you often end up re-trying the original case in the malpractice trial, which makes these cases complex and often expensive.

Professional liability for other fields: While I’ve focused on legal malpractice for illustration (since I’m writing as an attorney), similar principles apply to other professions:

- Medical Malpractice: A patient must show the doctor deviated from the medical standard of care (usually through another doctor’s testimony) and that this caused injury. Maryland has specific procedures and even caps on non-economic damages for medical malpractice cases.

- Accountants/Financial Advisors: Suppose an accountant’s miscalculation leads to IRS penalties for a client, or a financial advisor’s negligence causes investment losses. The client can sue to recover those financial losses as damages, under a theory that a competent professional wouldn’t have made such an error.

- Contractors/Architects/Engineers: If a construction professional’s negligence leads to a building defect or collapse causing economic loss or injury, they could face tort claims (though sometimes these get into contract law issues, which can limit tort claims due to economic loss doctrines – beyond our scope, but worth noting).

Defenses in professional cases: Professionals often have multiple defenses. They might argue they did meet the standard of care and that the outcome was not their fault (for example, “Even a competent lawyer could have lost that case – the client’s position was weak regardless”). They may also argue that the client’s own actions contributed, e.g., in an accounting case, the client may have given the accountant incorrect information. Also, as mentioned, the statute of limitations or lack of privity can be a defense (if someone not entitled to sue tries to sue, or if too much time has passed). Another interesting aspect: professionals sometimes say “an error in judgment is not negligence,” especially doctors. If there were two medically accepted approaches to a situation and the doctor chose one that turned out poorly, that’s not negligence as long as it was an acceptable approach. For lawyers, losing a case doesn’t automatically mean malpractice if the lawyer otherwise did everything reasonably well – you can do everything right and still lose a case (judges and juries can be unpredictable). The question is whether the lawyer’s methods were within the standard of a reasonably competent attorney.

Insurance for professionals: Most professionals carry professional liability insurance (malpractice insurance). Lawyers in Maryland aren’t required by law to have it, but many do. Doctors and hospitals certainly do. If you are a professional and get sued, your malpractice insurer typically hires a defense attorney to represent you. From the claimant’s side, if you sue a professional, often it’s the insurance that will ultimately pay any settlement or judgment (up to policy limits), not the individual out-of-pocket – although trust me, no professional likes to be sued; it’s stressful and can harm their reputation.

A quick local note: Montgomery County has many highly regarded professionals, but mistakes can happen anywhere. We have had legal malpractice cases in our courts, and medical malpractice cases are also often filed (though those frequently end up in Baltimore City or other venues depending on where the hospital is, etc.). If you believe you’ve been a victim of professional malpractice, it’s wise to consult an attorney who understands that field – these cases can be tough and require expert analysis. Conversely, if you are a professional worried about liability, take heart that as long as you act within accepted standards and document your work carefully, you’re largely protected. Also, building good client relationships helps – some disputes arise simply from poor communication rather than actual negligence.

Now, let’s turn to a different but related battleground: insurance disputes. This is about when your own insurance company doesn’t live up to what you see as its end of the bargain. We’ll explore what Maryland law says about insurers denying claims or delaying payment, and what recourse policyholders have.

Chapter 5: Insurance Litigation – Claim Denials and Coverage Disputes

We pay our insurance premiums faithfully, hoping we never actually need to make a claim. But when something bad happens – a car accident, a house fire, a lawsuit against us – we expect our insurer to be there to cover the loss or defend us. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always go smoothly. Insurance litigation refers to legal disputes between policyholders and insurance companies, often over denied claims, policy interpretations, or the insurer’s failure to defend/indemnify in a lawsuit. These disputes are quite common in Maryland courts. In Montgomery County, I’ve seen homeowners fighting insurers over storm damage claims, businesses clashing with insurers over coverage for lawsuits, and drivers suing over unpaid accident benefits. Let’s unpack what your rights and remedies are in these situations.

When can you sue your insurance company? Typically, if an insurer refuses to pay a claim that you believe is covered, or if they refuse to defend you in a lawsuit (when you have liability coverage that should provide a legal defense), you may end up in litigation. The legal claims can include breach of contract (the insurance policy is a contract, and you assert they breached it by not honoring coverage) and, in some cases, “bad faith” handling of the claim. Maryland has historically been conservative about allowing tort lawsuits against insurance companies for claim handling, but there are some important provisions to know.

- First-party claims (your own losses): In 2007, Maryland created a statutory cause of action for first-party insurance bad faith. This is sometimes called the “First Party Bad Faith Law,” and is codified in Md. Code, Courts & Judicial Proceedings § 3-1701 and Insurance Article § 27-1001. It basically says if your insurer fails to act in good faith in denying or handling your first-party claim (like a homeowner’s property damage claim or your own auto collision claim), you can file a complaint with the Maryland Insurance Administration (MIA) and eventually sue for remedies beyond the contract amount. However, Maryland’s version of this law is a bit toothless compared to some states – it limits the recovery to the amount due under the policy plus possibly your attorney’s fees, costs, and interest. It does not, for example, award punitive damages or the full range of your economic loss beyond policy limits. This has led some to call our bad faith law “weak”. In practice, if your house insurance wrongfully denies a claim for, say, $50,000 in damages, even if you prove bad faith, you usually can’t get more than that $50,000 (plus maybe legal expenses). The rationale was to impose a penalty (paying your fees) for clear bad faith, while not opening the floodgates to huge tort verdicts.

- Third-party claims (liability coverage): This is when someone sues you and you expect your liability insurer (like auto liability or homeowners liability) to defend you and pay any judgment (up to the policy limits). Here, Maryland recognizes a common law duty of insurers to act in good faith and settle claims within policy limits when it’s reasonable to do so. If they unreasonably refuse to settle and you get hit with a judgment above your policy limits, you can sue the insurer for the excess – that’s a classic bad faith failure to settle claim. Our Court of Appeals recognized this tort in cases like State Farm v. White (1967) and Maryland Auto. Ins. Fund v. Mesmer (1999). The idea is, that because the insurer has control of the defense and settlement decisions, it owes a fiduciary duty to look out for the insured’s interests and not just its own pocket. If the insurer, in “bad faith,” gambles and refuses to settle a claim that could have been settled within the $100,000 policy, and a jury then awards $300,000, the insurer can be liable to pay that extra $200,000 because it breached its duty. Maryland uses a good-faith standard – basically, did the insurer make an informed, honest, and diligent decision about settlement? If not, they’re on the hook for the consequences.

However, if an insurer simply denies coverage outright (saying “this claim isn’t covered under the policy”), Maryland law historically treated that as a contract matter, not a tort. An important case, Mesmer v. Maryland Auto. Ins. Fund, drew a line: if the insurer denies it has a duty to defend or indemnify you at all, then your remedy if they’re wrong is breach of contract – you typically can’t sue for tort damages (like emotional distress or punitive) in that scenario. You’d get whatever the contract said you should have gotten (like reimbursement of the legal costs you incurred because they refused to defend, etc.). Only when the insurer undertakes the defense and then fails to settle within limits does the tort duty kick in.

Practical impact: Suppose you own a small business in Rockville and you get sued by a customer for an injury at your shop. You have a $500,000 liability policy. The customer’s injuries are severe and they offer to settle for $500k (within your limits). If your insurer unreasonably refuses and the case goes to trial and the verdict is $1 million, you (the insured) could be personally on the hook for the extra $500k – a nightmare scenario. In that case, you would then likely sue your insurer for bad faith, to make them cover that $500k excess because they failed to protect you when they could have. Those cases are relatively rare (insurers usually settle if there’s a serious risk of excess judgment), but they do happen. The measure of damages in Maryland for that is basically the excess amount plus possibly interest – it’s essentially making the insured whole as if the policy had no limit.

Another common insurance dispute: denial of coverage. For instance, a homeowner’s insurer might deny a fire damage claim by citing an exclusion (like “we don’t cover intentional damage or certain water leaks,” etc.). Or an auto insurer might deny your PIP (personal injury protection) or uninsured motorist claim, arguing some fine print. In Maryland, if you think the denial is wrong, you can sue for breach of contract. Sometimes, you can also file a complaint with the MIA, which can investigate and even order the insurer to pay if it finds a violation of Maryland insurance regulations (the MIA is an administrative avenue that can be faster than court in some first-party disputes, and it’s actually a required step in many first-party bad faith claims under §27-1001 – you must give the MIA first crack at it).

Unfair claim practices: Maryland has an Unfair Claims Settlement Practices Act that lists things insurers shouldn’t do (such as refusing to pay without conducting a reasonable investigation or failing to attempt in good faith to settle when liability is reasonably clear, etc.). However, enforcement of that is typically through the Insurance Administration, not directly by private lawsuit (Maryland, unlike some states, doesn’t give you a direct claim for every unfair practice, except via the mechanisms mentioned).

Insurance company defenses: Insurers often defend by pointing to the exact language of the policy. Insurance policies are contracts with lots of conditions, exclusions, and definitions. A lot of insurance litigation boils down to interpreting what the policy covers. For example, after a hurricane, a big issue might be “was the damage from wind (covered) or flood (not covered)?” If flood is excluded, the insurer might deny saying the damage was due to flooding. These cases sometimes turn on expert opinions, but also on legal interpretation of the contract. Maryland follows the rules of contract interpretation – ambiguous policy language is typically construed against the insurer (because they wrote it), but clear language is enforced as written. So, an insurer might win a case by convincing the court “Look, the policy plainly excludes what happened here, so we don’t owe payment.”

Another defense is compliance with procedures: If a policyholder doesn’t follow the claim procedures (like failing to give prompt notice of a loss, or not cooperating in the investigation), the insurer might deny on that basis. Those fights can become part of litigation too – whether the insured really breached those duties and if that actually prejudiced the insurer.

Real-life example: Let’s say a Bethesda homeowner has a pipe burst, flooding the basement. They file a claim for water damage. The insurer delays and then denies, claiming the damage was due to “gradual seepage over time,” which might be excluded, rather than a sudden burst. The homeowner feels that’s wrong – it was a sudden incident – and also feels the insurer handled the claim poorly (maybe lost paperwork, took forever, etc.). The homeowner can file a complaint with the MIA alleging la ack of good faith. The MIA would review if the insurer had a reasonable basis. If the MIA finds bad faith, it can award the homeowner their damages up to the policy limit plus reasonable expenses and legal fees. If either party disagrees with MIA’s decision, they can appeal to the circuit court for a de novo trial. This process was designed to encourage resolution without full-blown court, but it’s an extra hoop to jump through.

Now, say the insurer simply denied coverage, period, and the homeowner had to pay out of pocket to fix their home. The homeowner can sue in court for breach of contract to recover those costs. If they win, they get what the policy should have paid. Can they get more? Under the statute, they might get attorney fees if they proved the denial was in bad faith. But generally, Maryland doesn’t allow punitive damages against insurers in these first-party cases (unless perhaps you found an independent tort like fraud).

Another scenario: A Gaithersburg driver has an auto policy with uninsured motorist (UM) coverage. They get hit by a hit-and-run driver and suffer injuries. Their own insurer lowballs or denies the UM claim (maybe alleging the injuries aren’t that serious or that coverage doesn’t apply for some reason). In Maryland, UM claims can be taken to court like a normal lawsuit against the insurer (or sometimes to arbitration if the policy requires it). It effectively becomes you suing your insurance company for the damages the uninsured driver caused. If the insurer doesn’t offer fair compensation, you can go to trial and have a jury decide the value, and then the insurer pays that (up to your UM limits). If the insurer acted egregiously (like no reasonable basis to deny), you might also pursue the bad faith route for fees.

From the insurer’s perspective: They argue that paying only what is contractually due is not bad faith if there was an honest dispute. Maryland’s bad faith law asks essentially: did the insurer lack a reasonable basis and act with knowledge or reckless disregard of that lack of basis? That’s a high bar to prove true “bad faith.” The majority of claim disputes are about contract interpretation or differing opinions on claim value, not malice on the part of the insurer. But for policyholders, it often feels like bad faith when you’re in the situation – you feel you’ve been paying premiums for peace of mind, and when you need help, the insurer isn’t helping.

Montgomery County angle: We have our local courts handle these cases, but sometimes insurance cases end up in federal court (if you and your insurer are citizens of different states and a lot of money is at stake, the insurer might “remove” the case to federal court in Greenbelt). Still, the law applied is Maryland state law. Locally, we see a fair share of disputes especially after major weather events (insurers denying certain property claims) or in complicated liability cases (like a question whether a certain business activity was covered by the policy).

As a policyholder, what can you do? Read your policies – know what’s covered and what isn’t. Document everything when you have a claim – keep emails, notes of calls, photos of damage. If an insurer denies a claim and you truly believe it’s wrong, consult an attorney who understands insurance law. Sometimes a strong letter from a lawyer can prompt an insurer to reevaluate. The Maryland Insurance Administration is also a resource – they even have an online complaint process. They can’t force an insurer to pay beyond policy terms, but they can pressure insurers on regulatory compliance.

To wrap up this chapter, remember: insurance is supposed to be a safety net, but disputes can arise. Maryland law gives you tools to challenge an insurer, albeit with some limitations. Don’t be afraid to advocate for yourself – insurers have plenty of lawyers, and sometimes you need one too to level the playing field.

Chapter 6: Conclusion – Navigating the System and Protecting Your Rights

We’ve covered a lot of ground: from someone slipping on your front steps in Montgomery County, to a client accusing a professional of bad advice, to wrangling with an insurance company over a denied claim. What should you, as a homeowner or business owner (and simply as a citizen), take away from all this? Here’s my BLUF again in different words: Be informed, be prepared, and don’t hesitate to seek help.

1. Prevention is key: A bit of foresight can save you from lawsuits. Maintain your property safely – fix hazards, use those wet floor signs, shovel that snow. If you’re a professional, document your advice and double-check critical work (like deadlines or calculations). While you can’t prevent every accident or error, showing that you took reasonable care can not only reduce the chances of harm but also provide a strong defense if something does happen.

2. Insurance, insurance, insurance: I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to have the right insurance coverage. It’s not just about paying premiums – it’s about peace of mind and financial protection. For homeowners in places like Potomac or Chevy Chase, a homeowner’s policy is a must (and usually required by mortgage lenders). Make sure it includes personal liability coverage. For business owners in Rockville or Germantown, a general liability policy and perhaps professional liability coverage (if you provide professional services) are vital. Review your policies annually; life changes and business changes may require updates or riders. Also consider umbrella insurance if you have significant assets – it provides extra liability coverage beyond your base policies.

3. Know your rights (but also your limitations): If an incident occurs, know the basics of what to do. If you’re injured by someone’s negligence, you generally have three years to file a lawsuit in Maryland (there are exceptions, but that’s a good rule of thumb). Don’t wait until the last minute; evidence can fade. If you’re the one being sued or who caused an injury, notify your insurer immediately and let them handle it (that’s what you pay them for). Understand Maryland’s quirks like contributory negligence – it may affect how you approach a claim (for example, an injured person’s lawyer will be looking to defuse any allegation that their client was also negligent, because it’s all-or-nothing here). If you’re a plaintiff, be prepared for the defense to scrutinize your actions closely due to that rule.

4. Montgomery County specifics: Our county is a microcosm of many legal issues. We have dense urban areas, suburban neighborhoods, high-tech businesses, medical facilities, you name it. That means our courts see a variety of tort cases. The Montgomery County Circuit Court in Rockville is known for handling complex civil cases efficiently, but also note: if your claim is smaller (under $30,000), it might be in District Court, which is a different process (no juries, often quicker hearings). If you’re filing a lawsuit or get sued here, consider hiring an attorney familiar with the local courts – local rules and customs can subtly affect a case.

5. The value of legal counsel: I might be a bit biased as an attorney, but as the People’s Law Library notes, personal injury and tort cases are generally not ideal for self-representation. The laws can be complex, and the other side (be it an insurance company or a corporation) will almost certainly have legal representation. A consultation doesn’t mean you have to hire a lawyer on the spot, but it can clarify your options. Many personal injury lawyers work on contingency (meaning they only get paid out of a settlement or judgment), which can help plaintiffs who can’t afford hourly fees. On the defense side, if you have insurance, they’ll assign a lawyer to you; if not, investing in a lawyer is usually worth it when a lot is at stake.

6. References and resources: If you’re interested in more detail, Maryland has a People’s Law Library online (which I cited in this blog) that explains personal injury law basics in plain language, including defenses like contributory negligence. Reading up there can reinforce what we’ve discussed. Also, the Maryland Judiciary website can give you info on local courts, and the Insurance Administration site has guidance on filing complaints. I included some citations to actual Maryland cases (like Maans v. Giant for slip-and-fall, Bennett v. Gentile for legal malpractice privity, and the statutes for insurance claims) – not because you need to become a legal scholar, but to show that these principles are backed by real law in our state.

7. Don’t panic, but do act: Finding yourself in a legal dispute – whether you’re injured or being blamed – is stressful. I’ve sat across the desk from folks in Rockville who are sweating over a court summons, and from accident victims in Silver Spring who are hurt and frustrated that the insurance company won’t pay. The best advice I can give is: take a deep breath, and then take action. If you’re hurt, get medical treatment (also important for documentation). If you’re sued, make sure you respond in time (ignoring a lawsuit can lead to a default judgment against you). Lean on professionals to guide you – that could be an attorney, but also sometimes mediators or insurance adjusters can help resolve things without a court battle.

In closing, Montgomery County is a wonderful place to live and work, but it’s not immune to the everyday legal issues that arise everywhere. By understanding tort and personal injury litigation basics, you’re better equipped to handle those issues. Think of this knowledge as another form of insurance – something you have but hope you won’t need to use. And if you do need to use it, remember you’re not alone. As Basil M. Al-Qaneh, Esq., I’m here in the community alongside many other legal professionals, ready to help our neighbors navigate the twists and turns of the legal system. Stay safe, take care, and know that if life throws a legal curveball your way, you have the tools and support to handle it.

Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Maryland, Virginia, & DC attorney.)

References

- Maans v. Giant of Maryland, LLC, 161 Md. App. 620, 871 A.2d 627 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 2005) – (Premises liability case requiring proof that the owner had knowledge of a hazard).

- Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Goodman, 275 U.S. 66 (1927) – (An early contributory negligence case, illustrating the harsh all-or-nothing rule).

- Maryland Courts & Judicial Proceedings Article § 5-101 – (Statute of limitations of three years for civil actions).

- Coleman v. Soccer Ass’n of Columbia, 432 Md. 679, 69 A.3d 1149 (2013) – (Maryland Court of Appeals decision refusing to abolish contributory negligence, deferring to the legislature).

- Flaherty v. Weinberg, 303 Md. 116, 492 A.2d 618 (1985) – (Established the strict privity rule in legal malpractice; attorneys generally owe a duty only to their clients, not third parties).

- Bennett v. Gentile, 478 Md. 123, 273 A.3d 846 (2024) – (Maryland Supreme Court decision reaffirming strict privity in legal malpractice and the narrow third-party beneficiary exception).

- Mesmer v. Maryland Auto. Ins. Fund, 353 Md. 241, 725 A.2d 1053 (1999) – (Clarified that an insurer’s wrongful refusal to defend is a breach of contract, and recognized the tort of bad faith failure to settle within policy limits).

- Maryland Insurance Article § 27-1001 and Courts & Judicial Proceedings § 3-1701 – (Maryland’s first-party insurance claim bad faith statute, allowing recovery of expenses and fees for lack of good faith in claim handling).

- State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co. v. White, 248 Md. 324, 236 A.2d 269 (1967) – (Early case holding that an insurer may be liable for the excess verdict if it fails to settle a claim against its insured in bad faith).