Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

Tysons Corner, Virginia, is undergoing a dramatic transformation from a suburban commercial hub to a high-density urban center. This growth has spurred complex land use and zoning challenges, pitting real estate developers eager to build against local residents concerned about traffic, livability, and fair process. Virginia’s legal framework – from comprehensive planning to recent court battles over standing to sue local government decisions plays a pivotal role in how these disputes unfold. While ongoing development projects promise economic benefits, they also highlight the need to balance ambitious redevelopment with community interests. Ultimately, Tysons’ success story will depend on collaborative planning and legal clarity to ensure growth is both sustainable and inclusive.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Tysons Corner’s Transformation and Tensions

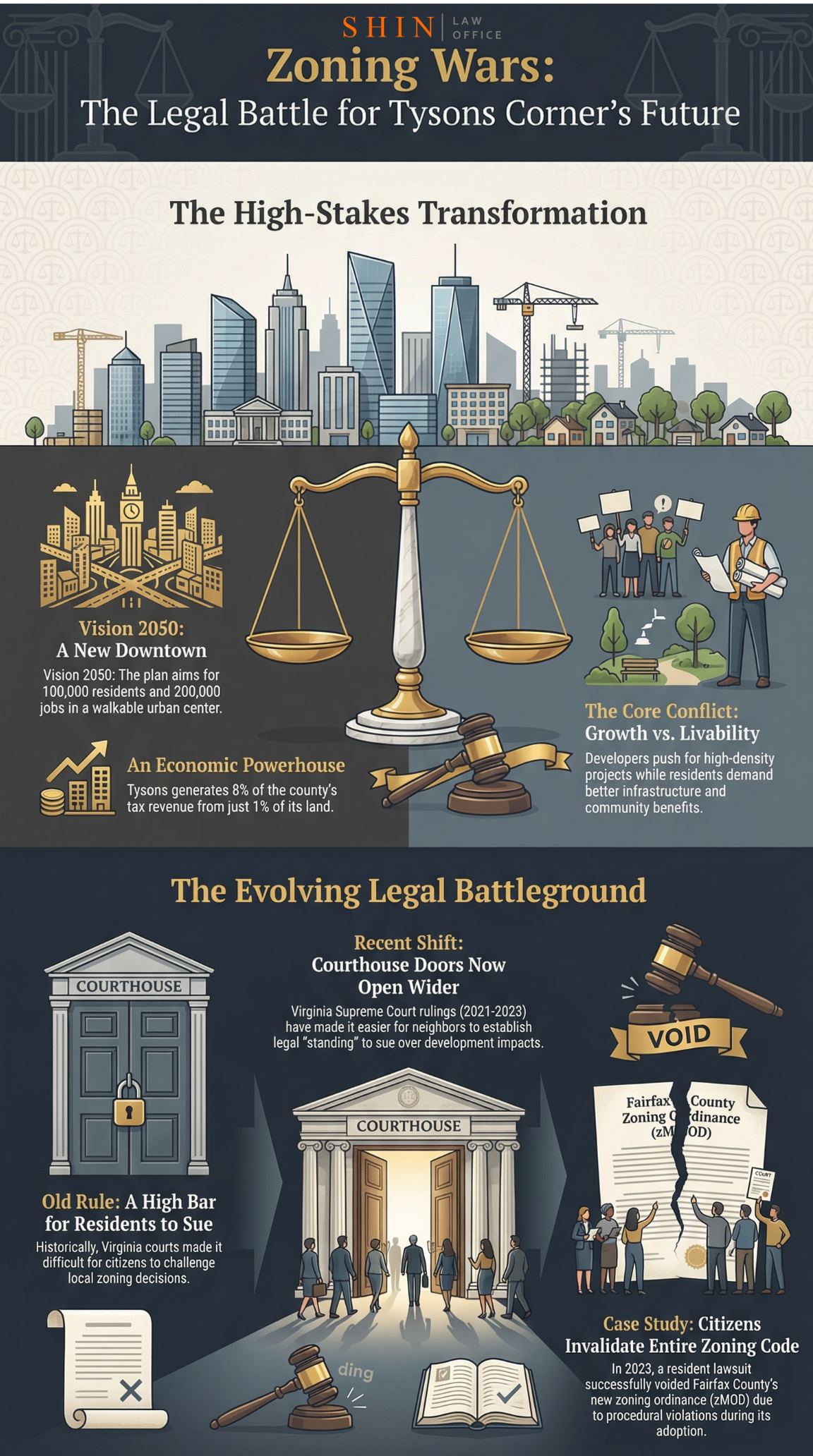

On a summer evening in Tysons Corner, a group of homeowners gathers at a community center to study site plans for a proposed high-rise. Across town, a developer’s team enthusiastically touts the same project’s benefits at a public meeting. This scene encapsulates the central tension in Tysons Corner: a fast-evolving urban skyline rising from what was once a highway-bound suburban retail zone, and a community coming to grips with the pace and impact of this change. Tysons Corner – an unincorporated area in Fairfax County, VA, just outside Washington, D.C. – has been aggressively reinventing itself under a 2010 Comprehensive Plan that encourages dense, transit-oriented development. In fact, that plan enabled “thousands of new multifamily housing units” to be built or approved in what had been a traditionally low-density, affluent suburban jurisdiction – “a rare accomplishment in the United States”. The vision is to transform Tysons from a sprawling “edge city” of parking lots and office parks into a walkable urban center with a mix of offices, apartments, shopping, and entertainment. By 2050, the goal is to house 100,000 residents and 200,000 jobs in Tysons, creating a vibrant “live-work-play” community on par with a true downtown.

This ambitious growth trajectory has made Tysons an economic powerhouse for the region, but it also places enormous strain on local infrastructure and quality of life. Tysons already generates about 8% of Fairfax County’s tax revenue from just 1% of its land area, and it’s home to major employers (Fortune 500 companies like Capital One and Hilton) and two of the nation’s largest shopping malls. One in five Fairfax County jobs is based in Tysons, underscoring why county officials and developers are so invested in its success. With the 2014 opening of Metro’s Silver Line stations in Tysons, developers see an opportunity for new high-rises around transit, and county leaders see a chance to channel growth into an urban center rather than further sprawl.

Yet, for local residents and neighboring communities, the rush of development brings palpable concerns. Longtime Northern Virginians remember Tysons Corner as a place of perpetual traffic jams on Routes 7 and 123; they worry that adding dozens of new high-rises will exacerbate congestion and strain public services. Newer residents drawn to Tysons for its emerging city vibe are also invested in its livability – they want walkable streets, parks, and schools to match the glossy new buildings. Thus, even as many welcome the convenience and amenities that redevelopment promises, they also ask tough questions: Will the new developments provide sufficient road improvements, transit options, and civic infrastructure (such as schools and parks) to support the influx of people? Are local leaders negotiating hard enough with developers to fund these improvements, or are projects being greenlit without adequate community benefits? And critically, how can ordinary citizens have a say in the transformation of their own backyard? These questions have led to numerous zoning disputes and public clashes in Tysons, reflecting a classic dynamic in booming communities – the push-and-pull between growth and preservation.

Tysons Corner’s very identity is at stake in these debates. Is it simply a corporate center to be built up as much as market forces allow, or a nascent community that should grow in a deliberate, people-friendly way? On one side, real estate developers argue that Tysons must densify to reach its potential as an urban hub, citing successes like The Boro, a new mixed-use district with apartments, offices, a Whole Foods, and a buzzy restaurant scene, all built near a Metro station. They point out that Tysons’ ongoing evolution is already bearing fruit: the area’s population has roughly 30,000 residents now – a 75% increase since 2010 – and that growth has attracted more retail and nightlife, slowly shedding Tysons’ old image as a 9-to-5 office park. On the other hand, community groups and neighboring town councils caution that, without careful oversight, Tysons’ redevelopment could create more problems than it solves. They highlight current pain points – traffic that still clogs major arteries, pedestrian-unfriendly roads, and a relative lack of “human-scale” street life – noting that Tysons remains only “somewhat walkable” by urban standards. As one observer quipped, building a walkable downtown in Tysons isn’t easy when “the place sprung up around highways”.

In this charged atmosphere, zoning and land-use decisions serve as the battleground for Tysons’ future. Every rezoning application for a taller building or denser project can become a proxy war between pro-growth advocates and wary residents. Public hearings overflow with passionate testimony both for and against development proposals. Sometimes disputes even spill into the courts. In short, Tysons Corner’s transformation has been accompanied by tension and conflict. Understanding how these disputes arise – and how Virginia’s laws mediate them – is key to making sense of what’s happening on the ground in Tysons. The following chapters explore the legal framework that governs land use in Tysons, the evolving rights of citizens and developers to challenge or defend zoning decisions, real examples of contentious projects, and how the community might strike a balance going forward. Tysons may well become a blueprint for other suburban areas eyeing urban redevelopment, but its path is proving anything but smooth.

Chapter 2: Land Use and Zoning Framework in Virginia

Tysons Corner’s redevelopment doesn’t occur in a vacuum – it operates within Virginia’s land use planning and zoning framework. This framework is the rulebook that determines how land can be used, how new development gets approved, and how the public can participate in shaping those outcomes. To understand zoning disputes in Tysons, one must first understand how the system is supposed to work in Virginia.

Planning and Zoning Basics: In Virginia, every locality (county, city, town) is required by state law to adopt a Comprehensive Plan as a guide for long-term land use and development (Va. Code Ann. § 15.2-2223). Fairfax County’s Comprehensive Plan sets broad development policy; in 2010, it was amended with a special Tysons Corner Urban Center section that reimagined Tysons as a dense urban core. This plan laid out targets for housing and jobs, urban design guidelines, and even specified which parts of Tysons should have the tallest buildings (generally near the Metro stations) and which areas should taper down to respect adjacent residential neighborhoods. The Tysons plan was groundbreaking, and its creation involved years of collaboration between stakeholders. A county-appointed Tysons Land Use Task Force (2005–2010) – consisting of local homeowners, business representatives, and transit advocates – spent thousands of hours gathering input and crafting recommendations. The result was a Comprehensive Plan amendment that the Board of Supervisors adopted in 2010, effectively rewriting the future of Tysons. Crucially, the task force’s mandate was to decide how Tysons would be redeveloped, “not whether” it would be – as the Task Force chairman, Clark Tyler, put it, stopping growth was “not realistic because it’s extremely valuable, privately owned land with by-right zoning”. In other words, development was coming one way or another, so the community’s best move was to shape it. This philosophy of proactive planning helped integrate community priorities (like buffering nearby single-family neighborhoods and requiring public amenities) into the plan.

Once a Comprehensive Plan is in place, implementation occurs through the zoning ordinance and individual zoning decisions. Virginia law empowers local governments to adopt zoning ordinances to regulate land use (e.g., dividing land into residential, commercial, and industrial zones, setting height and density limits, etc.). Fairfax County’s zoning ordinance specifies what can be built in Tysons and under what conditions. Notably, to realize the vision of the Tysons Comprehensive Plan, the county created new “Planned Tysons” zoning districts that allow high-density, mixed-use projects – but only if developers commit to certain contributions and design standards. In practice, most major developments in Tysons require a rezoning: the developer must apply to change the site’s zoning to a category that permits the desired height or mixed-use density. This is a legislative process involving public hearings, negotiation of proffers (voluntary developer commitments), and approval by the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors. Public participation is built into this process – state law mandates that rezonings and zoning amendments be advertised and subject to hearings at which citizens can comment (Va. Code Ann. § 15.2-2204). In Fairfax, the Planning Commission (an advisory body of appointed citizens) reviews each proposal first, often holding its own public hearing and making a recommendation. Then the Board of Supervisors holds another public hearing and makes the final decision. Residents, neighboring property owners, and local citizen associations often turn out en masse at these hearings if a project is controversial. For example, if a developer seeks to build a 30-story condo tower near a border with a single-family neighborhood, you can expect to hear concerns about traffic overflow, school capacity, and blocked views voiced by nearby homeowners at the hearing, while supporters might talk about new shopping or housing options the project brings. Elected officials have to weigh these inputs alongside technical staff reports and the Comprehensive Plan’s guidance.

Zoning Challenges in Tysons: Tysons Corner’s massive redevelopment has posed some unique zoning challenges. One is coordinating infrastructure with growth: the county’s plan conditions high-density development on improvements like new grid roads, expanded transit, and public facilities. Fairfax often uses proffers in Tysons to have developers help fund these. For instance, developers might proffer to build a new road segment, contribute to a new school or fire station, or set aside land for parks in exchange for project approval. Over the past decade, this approach has yielded results – about 34 acres of new parkland have been opened to the public in Tysons since 2010, and development proffers have delivered amenities such as Capital One Hall (a performing arts center) and new community spaces at The Boro. These proffered benefits are intended to mitigate the impact of development. However, ensuring that each project “pays its way” remains a point of contention. Fairfax County periodically updates the proffer formulas (for example, in 2024, the county slightly increased the per-square-foot contributions Tysons developers must pay toward public facilities) to keep pace with needs. Developers, naturally, resist excessive exactions that could make projects financially unfeasible, while residents press officials to extract more concessions to offset the effects of growth. It’s a delicate balancing act written into zoning negotiations.

Another challenge is sequencing redevelopment without overwhelming existing infrastructure. The Tysons plan contemplated growth in phases out to 2050, but market forces don’t always proceed in an orderly fashion. For example, if too many office buildings go up before transit or road improvements are in place, traffic could temporarily worsen. The county’s implementation strategy tries to align approvals with infrastructure milestones (e.g. only allowing a certain amount of development until a new transit connection or roadway is built). Monitoring and enforcing these phased triggers can be complex and sometimes contentious – civic groups keep a close eye on whether the pace of construction is outstripping the promised infrastructure.

Zoning Administration and Enforcement: Not all land-use conflicts in Tysons involve massive rezonings; some arise from interpretations of existing zoning rules. Fairfax County has a Zoning Administrator who makes determinations on zoning compliance. These determinations (say, whether a particular use is allowed or whether a setback requirement applies) can be appealed to the Board of Zoning Appeals (BZA) by aggrieved parties. In Tysons, where most big projects are handled via rezoning, BZA disputes are less frequent, but they do occur (for instance, an appeal could be filed if someone believes a developer isn’t following their approved conditions, or if a neighbor disputes a staff decision allowing a certain use by-right). By state law, any person “aggrieved” by a BZA decision can appeal it to the circuit court within 30 days (Va. Code Ann. § 15.2-2314), which brings us to the crux of legal fights: Who is “aggrieved” enough to challenge a zoning decision in court? That question of standing – who has the right to sue – has become especially significant in recent Virginia land use disputes, and it is the topic of the next chapter.

Before moving on, it’s worth noting that the Dillon Rule in Virginia limits local government powers to those explicitly granted by the state. This means Fairfax County’s authority to manage Tysons’ growth (and to respond to community demands) is constrained by what the state legislature permits. For example, Virginia only recently (in the past decade) allowed localities to adopt certain mixed-use zoning tools and impact fees; likewise, state law changes in 2016 imposed strict limits on residential rezoning proffers, curbing what localities could ask of developers (though those rules were later relaxed in 2019). Such state-level rules form an often unseen backdrop to Tysons’ zoning battles – local officials must operate within a state-defined sandbox, even as citizens might call for things like rent control or binding traffic concurrency requirements that Virginia law doesn’t currently allow. This interplay between state law and local land-use controls sometimes frustrates residents and county leaders alike, prompting creative approaches (and occasional lobbying in Richmond for more flexibility).

In summary, Tysons Corner’s redevelopment is guided by a comprehensive plan and executed through case-by-case zoning decisions under Virginia’s legal framework. The process is designed to be transparent and participatory, but that doesn’t mean it’s devoid of conflict – if anything, the stakes in Tysons have made every step, from planning to permitting, a subject of intense debate. When those debates can’t be resolved through the normal planning process, they often escalate to legal battles, which we explore next.

Chapter 3: Legal Battles and Standing to Sue

When a controversial development is approved (or denied) in Tysons Corner, the fight often isn’t over. The venue simply shifts – from the hearing room to the courtroom. In land use disputes, lawsuits have become an extension of the political process, a last resort for those hoping to overturn decisions. But not just anyone can march into court to challenge a zoning decision. They must have standing, a legal stake in the matter, for the case to be heard. This chapter delves into the legal battles arising from zoning disputes and explains how Virginia’s standing-to-sue laws are evolving, determining who gets their day in court.

Imagine a scenario: The Fairfax County Board of Supervisors has just approved a rezoning for a new 20-story apartment tower in Tysons, over the objections of a nearby neighborhood that fears increased traffic on their local streets. The neighbors are furious – from their perspective, the county ignored their concerns. They consider suing to stop the project. Meanwhile, on another front, a developer whose project was denied by the Board believes the denial was unjust and considers suing the county to overturn the decision. In both cases, the threshold question is who has standing to sue and on what grounds. Standing is essentially the legal right to initiate a lawsuit, and it requires showing a particular harm from the decision at issue. Courts do not entertain generalized grievances – a plaintiff must demonstrate a concrete, personalized injury.

Standing for Neighbors and Community Groups: For citizens and community organizations opposing a development, Virginia’s standing doctrine historically set a high bar. In fact, Virginia jurisprudence on land use standing was relatively sparse and strict until about a decade ago. A key Virginia Supreme Court case, Friends of the Rappahannock v. Caroline County (2013), established a two-part test that became the standard: (1) the plaintiff must own or occupy real property within or near the affected site (proximity), and (2) the plaintiff must show a “particularized harm” to a personal or property right, different from that suffered by the public generally (distinct harm). If either prong was not met, the would-be challenger lacked standing. In Friends of the Rappahannock, for example – a case where neighbors objected to a proposed sand-and-gravel mining operation – the Supreme Court acknowledged the neighbors lived nearby but found their alleged concerns (noise, dust, effects on a child’s asthma, etc.) were too speculative and not specific enough to their properties, as opposed to general worries anyone might have. The court ruled those plaintiffs lacked standing and tossed out the challenge. Similarly, in other cases over the 2010s, Virginia courts often dismissed community lawsuits for failing to pinpoint a concrete injury. In one Fairfax County case, homeowners who opposed a zoning administrator’s decision were deemed not “aggrieved” because the decision merely set up a future approval step – no immediate harm was imposed, so they had no standing to appeal it. This strict approach made it “increasingly difficult for homeowners looking to fight nearby development in court,” as one legal commentator observed in 2015. Even when lawsuits failed, however, they could achieve one result: delays. Developers often complain that, win or lose, litigation by project opponents can add months or years and significant cost to a project’s timeline. This threat of costly delay gave community opponents some leverage, even if ultimate court victories were rare.

The Recent Expansion of Standing: In the last few years, the pendulum in Virginia has begun to swing toward a more permissive view of standing for neighbors. The Virginia Supreme Court has handed down a series of decisions (in 2021–2023) that make it easier for nearby landowners to challenge local land use approvals, opening the courthouse doors wider than before. These cases have broadened the interpretation of “particularized harm.” For instance, in Anders Larsen Trust v. Board of Supervisors of Fairfax County (2022), a group of homeowners challenged the county’s determination that a residential treatment center could operate by-right in their neighborhood. The Supreme Court found the neighbors did have standing, recognizing their allegations that the facility would bring increased traffic and lower their property values as valid particularized harms – far from speculative, given that their homes were immediately adjacent to the site. Likewise, in Seymour v. Roanoke County (2022), neighbors opposing a wildlife center’s expansion claimed it would increase traffic on their shared private road, posing safety hazards, noise, dust, and increased maintenance costs. The Court again ruled these alleged impacts could constitute the required specific injury, even though they resembled the type of concerns (traffic, noise) that had been dismissed in earlier cases. The difference was in the details – the Seymour neighbors shared an easement road, had already suffered some harm from increased use, and faced no mitigating conditions, so the Court found their situation sufficiently unique. Most recently, Morgan v. Board of Supervisors of Hanover County (2023) pushed the envelope further. In that case, residents challenged approvals for a massive Wegmans distribution center near their rural properties, citing worries about semi-truck traffic and light pollution. The Virginia Supreme Court found standing, effectively holding that traffic and even ambient light impacts could constitute particularized injuries when tied to a specific large project. Taken together, these decisions mark a notable shift: Virginia courts are now more inclined to let neighbors have their day in court, even when the impacts earlier might have been deemed “too general.” One legal analysis noted that this trend “increased litigation risk” for developers seeking rezonings and special permits, since neighbors can more readily challenge approvals in court. In Tysons Corner, where many projects abut existing communities or create area-wide impacts, this expanded standing doctrine empowers local residents to press legal challenges if they feel the county approved a project without adequately addressing its fallout. Developers and the county must be mindful that decisions can be second-guessed by judges if proper procedures and reasoned justifications aren’t followed.

That said, standing is only the first hurdle. Winning a land use lawsuit is another matter. Virginia courts generally defer to local legislative decisions (like rezonings) under the “fairly debatable” standard – meaning if the decision had any reasonable support, the court won’t overturn it. The typical remedy residents seek is a court order voiding the approval (or halting the project), not monetary damages. It’s rare for a court to flat-out block development in Virginia; more often, legal challenges might force a redo of the process or a modification. But there are exceptions. One high-profile example is the zMOD case in Fairfax County, which involved a procedural challenge with dramatic results. In 2021, Fairfax County’s Board of Supervisors adopted a comprehensive overhaul of its zoning ordinance (known as zMOD) in an entirely virtual meeting – it was early in the COVID-19 pandemic, and public gatherings were restricted. A group of residents (led by David Berry and others) sued, arguing that passing such sweeping changes via an online meeting violated the state’s open meetings law. In 2023, the Virginia Supreme Court agreed and invalidated Fairfax’s new zoning ordinance as “void ab initio” – essentially nullifying it from the start. The Court held that the Board’s electronic meeting violated the Virginia Freedom of Information Act (VFOIA) requirements in effect at the time, and it struck down zMOD in its entirety. This stunning decision briefly threw Fairfax’s development regulation into chaos (reverting rules back to the prior 1978 ordinance) and proved that citizen-plaintiffs could, on procedural grounds, topple even a major county initiative. The standing in that case was not heavily contested – as taxpayers and residents, the plaintiffs were found to have the right to challenge an alleged FOIA violation by their government. But the case underscores how procedural missteps (like inadequate notice or unlawful meetings) open local decisions to attack.

In response to the zMOD debacle, the Virginia General Assembly passed special legislation in 2023 that retroactively validated local decisions made during electronic meetings during the early pandemic. Fairfax County’s Board, armed with that new state law, moved to reinstate zMOD in mid-2024, claiming the law “retroactively” cured the FOIA issue. However, the same residents and their attorney argue that the legislature cannot simply reverse a final court judgment and breathe life back into an ordinance the Supreme Court declared void, calling it an unconstitutional breach of separation of powers. As of this writing, the legality of reinstating zMOD under the new law is likely to head into further litigation, demonstrating the ongoing tug-of-war between different arms of government and the public. This episode highlights that citizen lawsuits can influence not just individual projects but also the very rules of the game, prompting both judicial and legislative responses.

Developers in Court: Thus far we’ve focused on residents suing to stop development, but developers themselves also resort to legal action when they believe a project was unfairly denied or held up. In Virginia, it’s difficult for a developer to win a lawsuit overturning a legislative denial (because of that deferential “fairly debatable” standard), but there are avenues for relief, especially if a constitutional issue is at play. One path is to claim that a denial was so arbitrary or discriminatory as to violate rights, such as equal protection or fair housing laws. A vivid local example occurred just outside Tysons in the Town of Vienna: Sunrise Senior Living proposed an 82-unit assisted living facility in Vienna’s downtown, but the Town Council rejected the necessary rezoning in 2019 amid resident concerns about parking and density. Sunrise struck back with a $30 million lawsuit against the town, accusing officials of discrimination against seniors and disabled people under the Virginia Fair Housing Law, and arguing that its project met all the town’s planning guidelines. The lawsuit alleged the Council’s cited reasons (like parking shortages) were not backed by evidence and were “necessarily arbitrary and capricious”. In essence, Sunrise claimed the denial was unlawfully prejudiced and lacked a rational basis. Town officials vehemently denied any discrimination, maintaining that fair housing law didn’t apply as Sunrise suggested and that the Council had legitimate land-use reasons for its vote. The case put a spotlight on the legal protections (or lack thereof) for developers: while governments enjoy broad immunity for legislative zoning acts, there is a Virginia statute, Va. Code § 15.2-2208.1, that allows property owners to seek damages if a denial is proven “unconstitutional.” Such claims are hard to win – the developer must show no reasonable basis for the decision or an impermissible factor like discrimination. In Sunrise’s case, the Town moved to dismiss the lawsuit, and these kinds of suits often end in dismissal or settlement rather than a court ordering the rezoning approved. But merely filing a lawsuit can put pressure. At a minimum, it forces the local government to articulate a solid defense of its decision in court. And in some instances, it might lead to a negotiated compromise (for example, a revised project proposal) to avoid protracted litigation.

Appeals and Other Legal Tools: In addition to direct lawsuits, there are other legal avenues in zoning disputes. For administrative actions (such as site plan approval or a permit granted by county staff), aggrieved parties might seek a writ of mandamus or certiorari to challenge whether the action complied with the law. In Tysons, if a developer receives a contentious administrative approval (say, an interpretation allowing extra units), neighbors might appeal to the BZA or file in court if no other remedy exists. Virginia courts also recognize declaratory judgment suits for certain land use challenges – for example, a citizen might file a declaratory suit claiming a zoning amendment is void due to failure to follow procedure or inconsistency with the comprehensive plan. Indeed, claims of “inconsistency with the comprehensive plan” have been raised in some Virginia cases, but because comprehensive plans are generally advisory (except for specific requirements, such as Va. Code § 15.2-2232 for public facilities), such arguments face hurdles.

It’s important to note that not every grievance is actionable. Many residents speak in opposition at hearings and are unhappy with the outcome, but unless they have a direct, tangible interest – such as living next door or experiencing a specific harm – they cannot sue. And even when they can, courts will not substitute their judgment for that of local officials unless a clear legal violation occurred. As one judge famously said, courts are not “super zoning boards.” However, the fear of litigation imposes discipline on the process: Fairfax County (and developers) often proactively address community concerns to avoid lawsuits. For example, they might scale down a project’s height next to a neighborhood or add traffic mitigations as conditions, thereby undercutting a potential plaintiff’s claim of particularized harm. In this way, the legal standard of standing indirectly encourages negotiated solutions – essentially, by giving community members a credible legal threat, it motivates all parties to find compromise before final decisions are made.

In summary, the landscape of who can sue over zoning in Virginia is shifting. While it used to strongly favor developers and local governments (with neighbors having a very limited role in court), recent court decisions have empowered residents to challenge land use approvals when they can articulate concrete impacts. Tysons Corner, with its rapid redevelopment, has already seen legal battles emblematic of this trend – from residents voiding a county-wide zoning overhaul on procedural grounds to developers alleging bias in the denial of projects. The next chapter will look at some of these specific disputes and ongoing development controversies in Tysons, illustrating how the principles discussed so far play out in practice.

Chapter 4: Development Projects and Community Challenges

Tysons Corner’s skyline today is dotted with construction cranes and gleaming new towers – visible signs of progress, but also flashpoints for community debate. In this chapter, we examine several ongoing development and redevelopment projects in Tysons and the zoning disputes surrounding them. From lawsuits between corporate neighbors to grassroots backlash against zoning changes, these stories show how the collision of big development plans and local interests has manifested on the ground. Each case study sheds light on a different facet of land use conflict in Tysons.

The zMOD Saga – Modernizing Zoning Amid Protest: Perhaps the most sweeping recent dispute isn’t about one project at all, but about the rules governing all projects. Fairfax County’s zMOD initiative (short for Zoning Ordinance Modernization) was a comprehensive rewrite of the county’s antiquated 1970s-era zoning code. Adopted in March 2021, zMOD was meant to simplify regulations and enable modern land uses – such as easier approval for accessory dwelling units, home-based businesses, and flexible mixed-use zones – changes that would, among other effects, help Tysons develop with greater urban mixed-use vibrancy. However, because zMOD was approved during a fully virtual Board of Supervisors meeting (due to COVID-19), a group of Fairfax residents challenged its validity. In 2023, as noted earlier, the Virginia Supreme Court agreed with the challengers that the process violated open meeting laws and threw out zMOD in its entirety. This victory for the residents (who hailed from various parts of Fairfax, not just Tysons) had immediate consequences: the county reverted to its previous zoning ordinance, causing significant uncertainty for pending Tysons projects designed under zMOD rules. County officials, deeply concerned, quickly sought a fix. The Virginia General Assembly passed a law attempting to retroactively bless any pandemic-era virtual approvals. Armed with that, the Fairfax Board announced plans to re-adopt zMOD in 2024 and essentially reinstate the modernized code by July 1, 2024. But the residents who fought zMOD in court cried foul, arguing that the legislature cannot simply overwrite a court decision or cure a violation post hoc – as their attorney put it, having lawmakers resurrect zMOD after the Supreme Court struck it down “represents a violation of the separation of powers”. They contend that the new state law cannot apply to zMOD, perhaps because the case was already finalized, and are poised to litigate the matter further. The outcome of this power struggle has significant implications for Tysons: zMOD includes many pro-development reforms (for example, more permissive rules for higher-density housing and mixed uses in certain districts) that advance the Tysons Comprehensive Plan’s goals. If zMOD is reinstated successfully, developers will have a friendlier rulebook, but if it remains void, some planned Tysons projects might need to be re-evaluated under older, more rigid rules. From a community perspective, the zMOD fight wasn’t so much about Tysons specifically as it was about transparency and trust – the plaintiffs felt the Board pushed through significant zoning changes without proper public participation (holding virtual hearings that some people found hard to access or follow). That sentiment resonates in Tysons, where community members often stress the importance of being heard in zoning decisions. The zMOD saga is a cautionary tale: even well-intentioned reforms can backfire if the public feels sidelined. In Fairfax County, there is now heightened awareness that process matters – major land-use changes must be handled with the utmost openness, or they risk being invalidated and losing public legitimacy.

Developer vs. Developer: The Capital One Density Dispute: Tysons isn’t just a story of residents versus developers; sometimes it’s developers versus each other. A notable example dates back to the early days of Tysons’ transformation. In 2010, Fairfax County’s new plan upended previous development limits by allowing “landowners near the Metro to apply for unlimited density” in their projects. This was a radical policy designed to encourage maximum use of the land closest to the four new Metro stations. But it inadvertently sparked a feud between two major landowners: Capital One and CityLine Partners. Capital One owns a 26-acre campus in Tysons (around the McLean Metro station), where it envisioned a massive expansion including offices, residences, a hotel, and retail – a 4.4 million square foot mixed-use mini-city (which today features the Capital One headquarters tower, the tallest building in the D.C. region). Next door, CityLine Partners controls the adjoining tract (the former WestGate office park) and also planned a huge redevelopment (over 8 million square feet). Before the 2010 plan, these parties had a private agreement to share whatever limited development rights were available, to ensure neither would overwhelm local roads. But once the county opened the floodgates with unlimited density, Capital One wanted to throw out that old agreement and grab its fair share of the now much larger pie. CityLine, however, insisted the prior deal still bound Capital One to coordinate and possibly cap its development. In July 2011, this conflict hit the courts: Capital One sued CityLine (and a smaller adjacent owner) seeking a declaratory judgment that the old agreement was void given the “very substantial changes” in county policy. Capital One argued that clinging to the outdated formula would “prejudice [its] ability to plan, develop and construct” its project, effectively limiting what it could build. CityLine was taken aback – an executive VP said he was “surprised” by the lawsuit and unsure “why they’re doing it” – but clearly the stakes were high. If Capital One were forced to share its new Metro-proximity density, it might lose the opportunity to maximize its site. Industry watchers noted that this dispute could set a precedent affecting other Tysons landowners and any past covenants they may have. Fairfax County officials, for their part, stayed neutral but expressed hope that such private squabbles wouldn’t “slow the transformation of Tysons” or undermine cooperation on needed public improvements. In the end, this battle was resolved out of the limelight (likely settled privately), as both developments proceeded. But it highlights an interesting dimension of Tysons’ redevelopment: the complex interplay of private agreements and public policy, and how a dramatic change in zoning law (unlimited density incentives) can scramble prior expectations. It’s a reminder that zoning disputes aren’t always about stopping development – sometimes they’re about who gets to develop how much. When the rules of the game change, even allies can turn into litigants in pursuit of prime development rights.

Neighborhood Pushback at Tysons’ Edges: While much of Tysons’ growth has occurred in its core, largely insulated from single-family residential areas, the periphery of Tysons directly borders established neighborhoods (in Vienna, McLean, and Falls Church). These transition areas often become hotspots of contention, as residents fear the spillover effects of Tysons’ high density. A case in point is the Town of Vienna, which sits adjacent to Tysons’ southwest. Vienna has a small-town character by design – in fact, in 2020 its residents defeated a major rezoning initiative (Maple Avenue Corridor plan) that would have allowed taller mixed-use buildings in town. Town residents have been particularly wary of Tysons encroachment and cut-through traffic. The Sunrise assisted-living case discussed earlier was emblematic: Vienna’s Council cited parking and scale concerns in denying the project, reflecting the town’s cautious stance on density that even resembles Tysons-style development. Over in McLean (north of Tysons), a recent proposal to redevelop a shopping center into a mixed-use complex drew “pushback from nearby residents who say the project extends the business district into their residential area.” Residents and even the local county supervisor voiced reservations about suddenly placing a big commercial/residential project on the border of a quiet neighborhood, fearing it would alter community character and traffic patterns. In response, planners tweaked zoning proposals to soften those transitions – for example, by tapering building heights and requiring buffers. These edge disputes underscore a key challenge: Where does “Tysons urban” end and “suburban neighborhood” begin? The Tysons plan tries to address this with graduated intensity (highest near Metro, lower towards edges), but map lines can only do so much. As Tysons grows, coordination with adjacent jurisdictions (like Vienna) and neighborhoods is crucial. Fairfax County has, at times, had to defend its Tysons rezoning decisions in court from suits by those neighboring jurisdictions – though none very high-profile to date, it remains a possibility if, say, Vienna believed a Tysons project’s traffic impact wasn’t properly mitigated. More commonly, however, the county works diplomatically, adjusting plans or adding traffic calming measures at borders to keep relations smooth.

Infrastructure Strains and Community Demands: A recurring theme in Tysons zoning disputes is infrastructure: roads, transit, schools, and parks. Community advocates in and around Tysons often support redevelopment but insist that infrastructure must keep pace. For instance, the sheer volume of new housing has raised questions about school capacity – Fairfax County Public Schools are planning a new elementary school in Tysons and expansions elsewhere to accommodate growth. If those plans falter or funding lags, you can bet land use approvals will face resistance on the grounds that schools are overcrowded. Transportation is perhaps the hottest button. Even with four Metro stops now serving Tysons, the area’s internal street network is still developing. Tysons was built around car travel, and changing that DNA is a work in progress. The county’s goal is a grid of smaller urban streets to disperse traffic, but many of those grid connections rely on redevelopment to occur. As a result, traffic congestion remains a top concern. Residents frequently cite it in hearings, and it’s been leveraged in court arguments as well – recall that the Anders Larsen and Morgan cases hinged on traffic and road impacts being recognized as harms. In Tysons, developers usually must conduct traffic impact analyses and fund improvements (like intersection upgrades or contributions to transit projects) as part of rezoning approvals. Yet, during peak hours, Route 7 and Route 123 still grind along, testing everyone’s patience. Fairfax County has initiated studies on enhanced bus transit through Tysons and safer pedestrian crossings, but these are in various stages of implementation. Community groups, such as the McLean Citizens Association and Coalition for Smarter Growth, have at times applied pressure by testifying or even threatening legal action if they feel new developments are outpacing transportation solutions. One notable success on the community side has been the inclusion of robust bike and pedestrian plans for Tysons – developers now regularly incorporate bike lanes, trails, and better sidewalks in their site designs, something that might not have happened without persistent local advocacy for a less car-dependent Tysons.

Affordable Housing and Social Equity Issues: While not a “dispute” in the legal sense, a subtle tension underlying Tysons’ redevelopment is who benefits from growth. Fairfax County has set requirements for affordable/workforce housing in Tysons projects (for example, roughly 20% of new residential units must be set aside for moderate-income households). This policy has generally been embraced, and some developers even exceed the minimums, but community activists keep a watchful eye. They argue that with Tysons aiming for tens of thousands of new homes, it must also welcome families across income levels, not just the well-to-do. If, hypothetically, the county were to consider loosening those affordable housing requirements, that could trigger public pushback. Conversely, if a developer proposed a project perceived as excluding certain groups (like luxury condos with no affordable units), it might face a colder reception at hearings. Fairfax County’s commitment to housing equity has thus far prevented major strife on this front, yet the issue did surface indirectly in the Sunrise lawsuit – Sunrise claimed discrimination when their senior housing was denied, essentially arguing that community resistance to the facility was rooted in bias against a type of residents (elderly or disabled). Vienna officials strongly refuted that, but it shed a light on how social considerations intermingle with zoning decisions. As Tysons grows, ensuring it is developed as an inclusive community is part of the balancing act officials must perform, or else they risk lawsuits of a different nature (civil rights-based claims).

From these examples – county-wide zoning reform battles, inter-developer legal wrangling, neighborhood edge fights, infrastructure debates, and social equity concerns – it’s clear that Tysons Corner’s redevelopment is not without controversy. Each project or policy can become a microcosm of the larger growth dialogue. Yet, notable is how many projects do ultimately move forward. Despite the noise, many disputes are resolved via compromise: plans get tweaked, proffers get beefed up, and timing is adjusted. The legal challenges, while high-profile, have so far resulted in only temporary setbacks (even the zMOD voiding is likely to be resolved with either reinstatement or a quick re-adoption via proper procedure). Tysons in 2026 is undeniably forging ahead – construction continues on new high-rises, and the area is gradually maturing into the envisioned urban center. But the process has been, and will likely remain, iterative and sometimes contentious.

In the final chapter, we will discuss how Tysons Corner and communities like it can strive to balance the needs of development with residents’ concerns. The aim is to ensure that these zoning disputes lead to better outcomes – better projects, better plans – rather than becoming mere zero-sum fights. Tysons’ story is still being written, and the way these conflicts are managed will shape its trajectory for decades to come.

Chapter 5: Balancing Growth and Community Interests

Tysons Corner stands as a test case for how a community can reinvent itself through development while preserving a high quality of life for its residents. The stakes are enormous – get it right, and Tysons becomes a model “city of the future” in suburbia; get it wrong, and it could become an example of unbridled growth gone awry, or of opportunity squandered by paralysis. In this concluding chapter, we explore strategies for balancing real estate developers’ ambitions with local residents’ legitimate interests. We’ll look at how inclusive planning, strong partnerships, and perhaps some legal reforms can help turn zoning disputes from win-lose confrontations into win-win progress. The narrative of Tysons, at its best, is one of collaboration and compromise that leads to a dynamic yet livable urban community.

Community Engagement as a Cornerstone: One clear lesson from Tysons’ experience is the value of engaging stakeholders early and often. The 2005-2010 Tysons Land Use Task Force is frequently cited as a successful model of collaborative planning. By bringing together homeowners’ association leaders, environmental advocates, and major landowners in the same room, Fairfax County created a forum where concerns could be aired and understood, and creative solutions explored, long before formal hearings. Task force members, even those initially opposed to development, shifted from a stance of “no new growth” to one of mitigating the negative effects of growth, once they realized development was inevitable. They pushed for – and achieved – important safeguards in the plan (such as phased growth tied to infrastructure, height gradation near neighborhoods, and robust environmental standards). This doesn’t mean everyone got exactly what they wanted, but it built a sense of buy-in. Going forward, Tysons continues this approach through the recently established Tysons Community Alliance (TCA) – a non-profit improvement district that involves local businesses, residents, and government in guiding Tysons’ evolution. The TCA has been conducting extensive outreach, including community surveys on topics like transportation, parks, and housing, to “engage and elevate the voices of the broader Tysons community” in planning decisions. By institutionalizing a forum for dialogue, Tysons aims to ensure that adjustments to policies or new initiatives (such as future zoning amendments or public projects) reflect a consensus, or at least a compromise, among stakeholders. This proactive engagement can preempt many disputes – issues identified early can be resolved through plan changes or conditions, without resorting to lawsuits or eleventh-hour battles at public hearings. The more residents feel heard and see their input tangibly shape outcomes, the less likely they are to feel disenfranchised and head to court. For developers, participation in such forums can also be beneficial: it’s a chance to understand community priorities (say, a beloved green space that needs protection or a traffic shortcut that needs fixing) and incorporate those into their proposals, ultimately smoothing the path to approval. Regular communication builds trust. Even something as simple as a developer holding informal workshops with neighbors before submitting a rezoning application can turn a hostile crowd into a cooperative one by the time the public hearing arrives.

Transparency and Fair Process: Many conflicts are inflamed not just by the decision made, but by how it’s made. As we saw, the zMOD ordinance was struck down largely because citizens felt the process was too opaque or rushed under pandemic conditions. The remedy there is straightforward: adhere meticulously to open meeting laws, provide ample notice and accessible information, and when in doubt, go beyond the minimum requirements for public input. Fairfax County has learned from that incident – any future major change will likely involve extensive in-person outreach and perhaps hybrid participation options to maximize involvement. Additionally, clearly explaining the rationale for decisions can help. When the Board of Supervisors approves a contentious project, if they clearly state on record why – referencing how it meets the comp plan, how impacts are addressed, etc. – the public may not agree but can at least understand the reasoning. This also creates a solid record that can defend the decision in court if challenged (since judges look for evidence that the Board considered the relevant factors rather than arbitrarily disregarding them). On the flip side, if a project is denied, providing a detailed explanation (and tying it to legitimate land use objectives) can shield the county from developer lawsuits. In the Sunrise case, for instance, if the Vienna Town Council’s concerns about parking had been backed by a professional traffic study or clear findings, Sunrise’s claim of arbitrariness would be harder to argue. Consistent application of standards is another aspect – one cause of cynicism is when people perceive that a developer received special treatment or that the rules were bent. Maintaining consistency (or transparently justifying any deviations) helps build credibility that the system isn’t “rigged” in anyone’s favor.

Creative Problem-Solving: Balancing growth and community often requires thinking outside the box. Tysons has benefited from some creative solutions born out of dispute. For example, to address traffic concerns, developers and the county have embraced Transportation Demand Management (TDM) programs – committing to initiatives such as shuttles, transit subsidies for residents, and staggered work schedules in office leases – to reduce car trips. This was a direct response to community pressure to prevent new buildings from gridlocking roads. In some cases, when residents protested the loss of trees or open space, the solution was to incorporate public parks and plazas within new developments (the Arbor Row development, for instance, included new park space that helped alleviate community concerns). Another innovative tool has been phased approvals: the county might approve a large project but require it to be built in phases with check-ins. After the first phase, there might be a reevaluation of traffic or school impacts before later phases can proceed. This gave neighbors assurance that impacts wouldn’t run away unchecked. For developers, although it’s less certainty upfront, it provides a chance to prove that the project can coexist with the community, earning trust for future phases. Mediation and facilitated negotiations have also been employed. In a few high-tension cases outside Tysons, local governments have convened mediation between developers and community representatives to see if they can find common ground (for instance, agreeing to reduce one building’s height or to fund a community project as a concession). Bringing that tactic to Tysons disputes could be fruitful, especially where lawsuits are threatened – a mediated settlement can often produce a better outcome than a court win/lose scenario.

Legal Standing and Recourse – A Balanced Approach: The trend of expanding standing rights to citizens is double-edged. On one hand, it promotes accountability and gives communities a voice in court when they genuinely suffer harm. On the other, too lenient a standard could invite a flood of litigation that bogs down development in costly delays (which can also drive up housing costs, etc.). Virginia’s courts seem to be seeking a balance: they are allowing more claims to be heard, but they still scrutinize whether those claims have merit. From a policy perspective, the state legislature could help by clarifying certain aspects – for example, defining more concretely what counts as “aggrievement” in land use cases to reduce uncertainty. However, given the evolving case law, it might be wiser to let the judiciary adjust the doctrine gradually. Another possible reform often discussed is providing alternative dispute resolution venues for land use fights – perhaps a specialized land court or tribunal that can more quickly handle these challenges, or required arbitration for some disputes. That could make the process faster and less adversarial than a full lawsuit. As it stands, the prospect of a lawsuit is an important check in Tysons’ development process, but all parties likely agree that the court should be a last resort. Strengthening avenues for residents to be heard before final decisions (as mentioned, through engagement) is ultimately the best way to reduce the need for lawsuits.

Continuing the Vision – Flexibility and Commitment: Tysons Corner’s story is far from over. The Comprehensive Plan lays out a vision through 2050, but the world is changing – trends in remote work, for instance, are altering how much office space is truly needed. The plan may need updates (with public input) to remain realistic and relevant. Maintaining flexibility to adjust course, without abandoning the core vision, will be key. For example, if office demand remains weak, the county might pivot to allow more residential or even light industrial uses in some planned office areas – but that could alarm residents who fear different impacts. Handling such pivots will require careful community reassurance that the guiding principles (sustainability, livability) remain intact. Fairfax County officials often cite that Tysons will be a “work in progress” for decades, meaning they are open to incremental improvements and learning from experience. That kind of adaptive governance is crucial in balancing interests over the long haul. The commitment to public amenities and infrastructure must also remain unwavering. If at any point the community feels the county is selling out Tysons’ future (for instance, approving too many units without ensuring new schools or failing to secure promised road funds), the backlash will be fierce and justified. Thus far, the county has tied development approvals to an infrastructure funding plan, including significant contributions from developers, local tax districts, and state/federal funds. Continuing to transparently track and report on these improvements – basically, showing the community “we said we’d do X, and we have done/are doing X” – helps maintain goodwill.

Finding the Win-Win: The ideal outcome in Tysons’ zoning disputes is not a winner-takes-all scenario, but a solution that benefits both development and the community. Is that always achievable? Perhaps not always to the fullest extent each side would like, but many Tysons success stories have elements of win-win. Consider the Jones Branch Connector – a new road and bridge that now links two parts of Tysons across the Beltway. Developers of new buildings in that area contributed to its funding because it would give their tenants better access, while residents and commuters would benefit from reduced congestion. Or take the transformation of old parking lots into parks – developers may give up some buildable land to create a park, but that park increases the value of their adjacent buildings and makes the whole area more attractive (a boon to residents’ quality of life and the developer’s bottom line). When community benefits are packaged into development, everyone gains. The key is strong planning and negotiation to identify those opportunities. Even on the contentious issue of density, a win-win perspective can help: higher density near transit can actually reduce regional traffic (by promoting transit use and shorter commutes) and can take development pressure off suburban fringe areas. If pitched that way, even skeptics might see that focusing growth in Tysons could protect other neighborhoods and green spaces from sprawl – a broader benefit.

Finally, it’s worth remembering that developers and residents are not monolithic opposing camps. Many Tysons residents are young professionals or downsizers who moved because of the new developments – they welcome more restaurants, apartments, and shops. Likewise, some developers are Tysons residents or longtime landowners who care about community outcomes. There is overlap in the ultimate goal: a thriving Tysons Corner that offers a great place to live, work, and play. That shared vision can be the foundation for collaboration. As Providence District Supervisor Dalia Palchik (who represents Tysons) noted, improvements in Tysons – from transit to parks – are creating “the type of community that [people] want to call home”. If all parties keep that endgame in mind, disputes can be reframed from us-versus-them to a collective problem-solving exercise to reach that goal.

In conclusion, Tysons Corner’s journey of real estate development and zoning disputes teaches us that progress and preservation must go hand in hand. The land use battles – whether in hearing rooms or courtrooms – are not just fights over individual projects; they are negotiations over the soul and trajectory of the community. Through robust public engagement, transparent governance, legal empowerment tempered with responsibility, and an openness to compromise, Tysons is gradually finding its path. It’s a path where high-rises and single-family homes, new residents and long-timers, can coexist in a mutually beneficial balance. There will always be friction – change is hard – but Tysons Corner can remain compelling and relatable to both real estate developers (as a place where vision can be realized) and local residents (as a place they proudly call home). The cranes will keep climbing, and so, one hopes, will the trust and collaboration between all stakeholders. In the end, Tysons’ story may not be without controversy, but it can certainly have a positive, inclusive narrative – one where growth and community are not at odds, but in harmony.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

- O’Connell, J. (2011, July 10). Capital One and CityLine Partners enter legal dispute over Tysons Corner development rights. The Washington Post.Schneider, D. I. (2023, March 24). Supreme Court of Virginia invalidates Fairfax County Zoning Ordinance (Z-Mod). Holland & Knight Alert.FOX 5 DC Digital Team. (2024, June 12). Fairfax County residents challenge zoning rules amid legal dispute. FOX 5 News.Lloyd, T. P., Jr. (2025). The Virginia Supreme Court has made it easier for neighbors to challenge land use approvals – Here’s why it matters. Williams Mullen Legal Insight.Bean, Kinney & Korman. (2015, Jan 28). Fairfax Circuit Court limits homeowners’ ability to challenge Zoning Administrator. [Blog post].Montgomery, M. (2023, Nov 20). Tysons’ suburban-to-urban transformation still a work in progress. Axios.Moran, C. D. (2019, Aug 19). Vienna officials deny alleged discrimination in Sunrise lawsuit. Tysons Reporter.

Hamilton, E. (2020, Nov 3). How a Tysons task force built a road map for redevelopment. Greater Greater Washington.

Tysons Community Alliance. (2023, Aug 4). Latest market study reveals Tysons’ strong post-pandemic recovery led by residential growth [Press release].

Virginia Code Ann. § 15.2-2204 (2023). Advertisement of plans, ordinances, etc.; notice and hearing.

Virginia Code Ann. § 15.2-2208.1 (2023). Damages for unconstitutional grant or denial of permits or approvals by locality.

Friends of the Rappahannock v. Caroline County Board of Supervisors, 286 Va. 38, 743 S.E.2d 132 (2013).

Anders Larsen Trust v. Board of Supervisors of Fairfax County, 301 Va. 116, 871 S.E.2d 672 (2022).

Seymour v. Roanoke County Board of Supervisors, 301 Va. 156, 872 S.E.2d 169 (2022).

Morgan v. Board of Supervisors of Hanover County, 305 Va. 330, 883 S.E.2d 131 (2023).

Berry v. Board of Supervisors of Fairfax County, 303 Va. 208, 887 S.E.2d 328 (2023).