Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

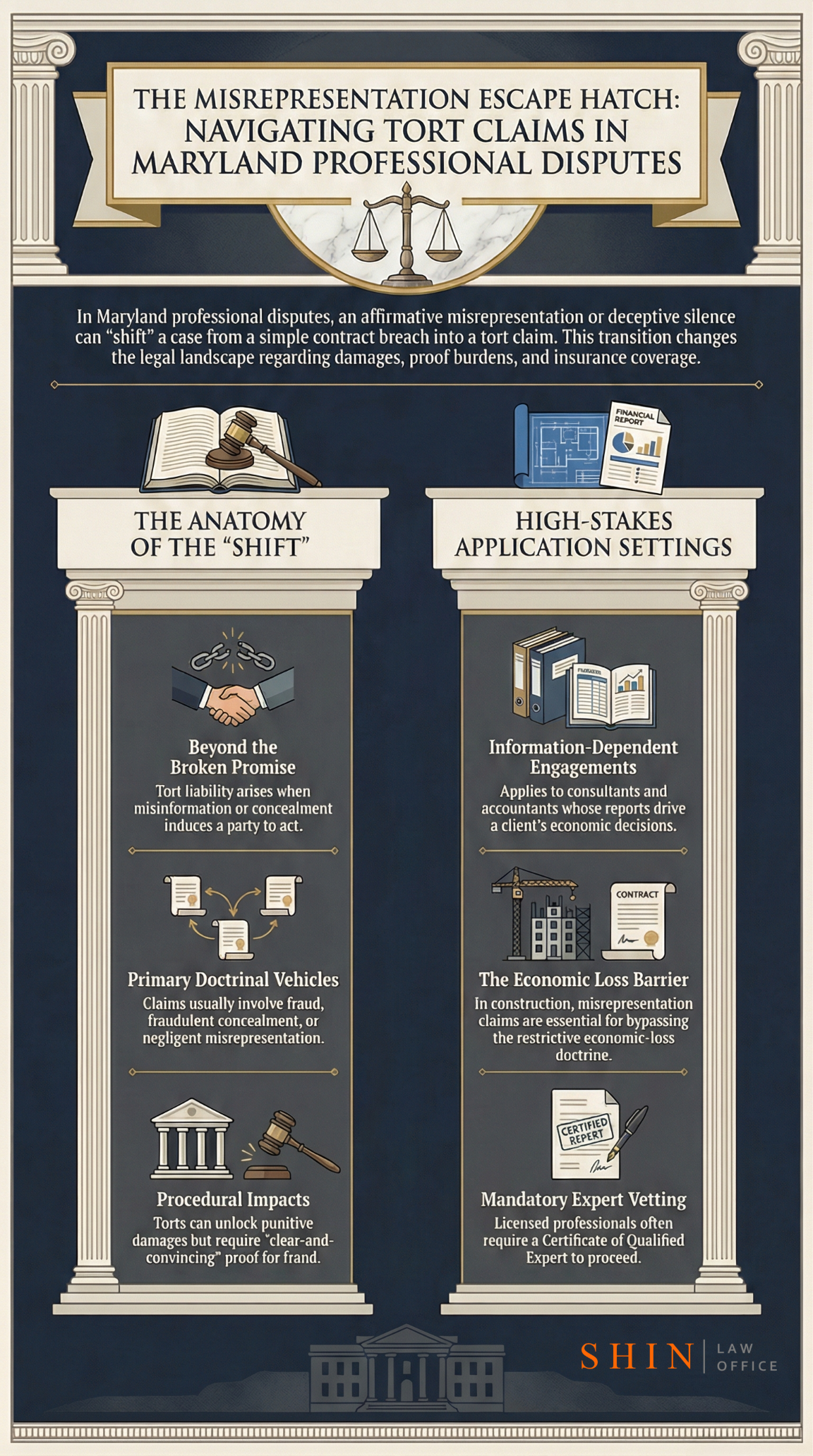

BLUF: In Maryland, a dispute that begins as a “broken promise” under a contract can shift into tort; sometimes dramatically, when one party’s affirmative misrepresentation, partial disclosure that becomes misleading, or knowing concealment/omission in the face of a duty to disclose creates (or evidences) a breach of an independent duty recognized in tort. The most common doctrinal vehicles are fraud (including fraudulent inducement), fraudulent concealment/non-disclosure where a duty to disclose exists, and negligent misrepresentation (often framed through the Restatement § 552 concept of information supplied for guidance). These tort theories can change leverage, available damages (including potential punitive damages for proven fraud), pleading burdens (clear-and-convincing proof for fraud), limitations defenses, insurance posture, and settlement dynamics.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Legal Framework

Chapter 2: Elements and proof

Chapter 3: When contractual breaches become torts

Chapter 4: Montgomery County specifics

Chapter 5: Practical guidance for consultants, contractors, and service providers

Chapter 6: Plaintiff and defense strategies

References

In my experience litigating and advising on professional services disputes, the practical inflection point is simple: Maryland courts do not permit plaintiffs to “tortify” every breach of contract, and they are wary of expanding negligence liability for pure economic loss absent a required nexus or exception. But when the conduct is not merely nonperformance—when it is misinformation, deceptive silence, or concealment that induces action—the analysis changes because the grievance is no longer just “you didn’t do what you promised”; it is also “you caused me to act (or refrain from acting) based on falsehoods.” Maryland’s high court has repeatedly emphasized that “not every duty assumed by contract” supports tort liability.

This “shift” matters most in three recurring settings in Montgomery County’s commercial docket:

First, information-dependent professional engagements (consultants, accountants, design professionals, brokers, technology vendors) where the client’s economic decisions turn on statements, reports, progress updates, certifications, and compliance representations. Maryland recognizes negligent misrepresentation with defined elements and compensates for pecuniary loss.

Second, construction and design disputes, where the economic-loss doctrine (or rule) is frequently invoked to confine parties to contract remedies—yet misrepresentation and concealment claims still appear when drawings, schedules, change conditions, and “status” statements are alleged to be false. Maryland’s treatment of economic loss in construction—including the network-of-contracts rationale and duty limits—frames what can realistically survive early motions.

Third, Montgomery County Business & Technology matters, where local trial-level opinions—though not precedent—often contain detailed reasoning on pleading sufficiency, duplicative tort counts, and reliance allegations. The Business & Technology Case Management Program’s published trial opinions are expressly not precedential, but they are informative about how judges may think through these issues in practice.

Finally, do not ignore procedural gatekeepers. For claims against certain licensed professionals (e.g., engineers, architects, land surveyors, landscape architects), Maryland’s certificate-of-qualified-expert statute may require early expert vetting, even when the claim is styled as a contract, if the gravamen is professional negligence.

Chapter 1: Legal framework

Maryland’s contract–tort boundary is best understood as a set of layered filters rather than a single bright-line rule. The first filter is conceptual: contract law enforces the parties’ bargained-for allocation of risk and remedies, while tort law enforces duties imposed by law (not merely by agreement). Maryland’s appellate decisions regularly warn that contract duties do not automatically convert into tort duties, which is why courts scrutinize whether the plaintiff is really alleging (a) nonperformance or (b) misconduct violating an independent tort duty.

Contract duties versus tort duties in Maryland

A foundational statement appears in decisions quoting the familiar proposition that “not every duty assumed by contract will sustain an action sounding in tort.” The logic is practical: if every disappointed expectation could be pleaded as negligence, contract limitations—liquidated damages, limitation-of-liability clauses, waivers of consequential damages, negotiated risk—would be undermined by tort remedies.

Maryland’s courts, therefore, look for something more than breach: misrepresentation, concealment, special relationships, statutory duties, or risks of physical harm. In economic-loss cases in particular, Maryland’s “intimate nexus” concept—satisfied by contractual privity or its equivalent—has been used to limit negligence exposure when the plaintiff’s injury is purely economic. This is the doctrinal bridge between “ordinary commercial disappointment” and “actionable negligence causing economic loss.”

Negligent misrepresentation and the Restatement § 552 idea

Maryland recognizes negligent misrepresentation as a tort with its own elements. Appellate opinions describe it as the traditional tort for negligent provision of information “for the guidance of others” in business transactions. Maryland decisions cite the classic formulation of negligent misrepresentation and treat pecuniary loss as compensable.

In professional information settings (accountants are the canonical example), Maryland has also addressed the scope of third-party liability. In the accountant-liability context, Maryland adopted a constrained approach (drawing from the three-part “Credit Alliance” style criteria), reflecting a policy concern about “liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class.”

Fraud, concealment, and false statements

Maryland’s law of fraud is stringent because of its consequences. Fraud must be proven by clear and convincing evidence, and the elements include false representation, scienter (knowledge of falsity or reckless indifference), intent to defraud, actual and justified reliance, and compensable damages.

Maryland also recognizes that fraud may be based not only on overt lies but on concealment or suppression of the truth—but “mere silence” is not actionable absent a duty to disclose. Where a party makes a partial or fragmentary disclosure that misleads because of incompleteness, the “legal situation is entirely changed,” and concealment theories may apply.

Maryland’s Consumer Protection Act provides an additional statutory framework where misrepresentation and knowing concealment are expressly included within “unfair, abusive, or deceptive trade practices,” including false or misleading statements, failure to state a material fact, and knowing concealment/suppression/omission of material fact with intent that a consumer rely. This statute sometimes functions as a parallel or alternative to common-law fraud theories in consumer-facing service disputes.

Economic loss doctrine in professional and construction disputes

Maryland uses the economic loss doctrine (often called the economic loss rule) to limit negligence claims seeking purely economic damages absent qualifying conditions (e.g., intimate nexus or physical injury/risk). Construction disputes illustrate the tension: judges recognize a “network of contracts” that allocates economic risk and often resist creating tort duties that would reallocate that risk (especially on public projects). Maryland’s high court applied the economic loss doctrine to bar certain contractor claims against design professionals on a government project, emphasizing contract-based risk allocation and declining to extend privity-equivalent duty analysis in that context.

Statutory overlays that matter in Montgomery County cases

Several Maryland statutes frequently shape strategy in “contract → tort” disputes even when the core wrong is misrepresentation:

Maryland’s three-year limitations statute for civil actions is the baseline.

Maryland recognizes tolling for fraudulent concealment: if knowledge of a cause of action is kept from a party by the fraud of an adverse party, accrual is deemed to occur when the fraud was discovered or should have been discovered with ordinary diligence.

For construction-related claims, Maryland’s statute of repose for improvements to real property can bar claims after defined periods, including provisions focused on architects, engineers, and contractors.

For malpractice claims against licensed professionals, Maryland requires a certificate of a qualified expert in many cases, with dismissal consequences and limited waiver/modification possibilities.

Table comparing key Maryland cases on contract versus tort, misrepresentation, and economic loss

| Case / authority | Court / year | Core doctrinal point (tort vs. contract / misrepresentation / economic loss) | Practice takeaway for consultants/contractors/providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesmer v. Md. Auto. Ins. Fund | Supreme Court of Maryland / 1999 | Reiterates that not every contract duty supports tort liability; distinguishes when contract-based duties do not become tort duties. | If the complaint is “you didn’t perform,” expect defense to frame the case as contract-only and attack tort counts as duplicative. |

| 100 Inv. Ltd. P’ship v. Columbia Town Ctr. Title Co. | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2013 | Uses Mesmer proposition; analyzes duties and remedies when negligence is tied to contract relationships. | Plead and prove what duty exists independent of contract terms; defense will argue contractual risk allocation governs. |

| Balfour Beatty v. Rummel Klepper & Kahl | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2017 | Applies economic loss doctrine in public construction; declines privity-equivalent extension; emphasizes construction’s contract network. | For design-professional claims, plaintiffs must identify a duty pathway that survives economic-loss limits; defendants should anchor in “network of contracts” rationale. |

| Walpert v. Katz | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2000 | Adopts constrained criteria for negligent misrepresentation duty to third parties in accountant context; addresses Restatement § 552 concepts and privity-equivalent reasoning. | If you publish or provide information for others’ guidance, your exposure depends on who you intended/understood would rely; draft reliance limits carefully. |

| Swinson v. Lords Landing | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2000 | States elements of negligent misrepresentation and focuses on duty and reliance. | Build (or attack) negligent misrep claims element-by-element; reliance and duty are early motion targets. |

| Hoffman v. Stamper (as applied/quoted) | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2005 | Confirms fraud’s clear-and-convincing standard and articulates elements. | Fraud pleading raises the plaintiff’s evidentiary bar; defense can use that to pressure early summary judgment. |

| Exxon Mobil v. Albright | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2013 | Reinforces reliance requirements and rejects attenuated third-party reliance theories in many circumstances. | Plaintiffs must show personal reliance (or a recognized exception); defendants should attack generalized “public reliance” theories. |

| Lubore v. RPM Assocs. (as quoted/applied) | Appellate Court of Maryland / 1996 | Explains that partial disclosure misleading by incompleteness can create actionable concealment; mere silence generally not actionable absent duty. | “Half-truths” are dangerous: progress updates and partial disclosures can create concealment liability. |

| Heavenly Days Crematorium v. Harris, Smariga | Supreme Court of Maryland / 2013 | Enforces certificate-of-qualified-expert requirements for claims against licensed engineers/employers; discusses waiver/modification. | Early certificate compliance is case-dispositive. Defense should evaluate immediate dismissal options; plaintiff must plan expert retention early. |

| Md. Code Ann., Com. Law § 13-301, § 13-408 | Statute | Defines deceptive practices (including false statements, omissions, knowing concealment) and authorizes private actions for injury/loss plus potential attorney’s fees. | In consumer-facing service disputes, statutory claims may amplify settlement leverage and fee exposure; confirm whether transaction qualifies as “consumer.” |

Chapter 2: Elements and proof

If a case is going to “shift” from contract to tort in Maryland, it will do so through proof—meaning (a) the plaintiff must be able to plead and later prove the elements of the tort, and (b) the plaintiff must survive the recurring early-motion attack: “this is just contract dressed up.” In this chapter, I lay out the elements and the evidence that usually matters most, with a professional-negligence lens.

Negligent misrepresentation: what plaintiffs must prove, and where they usually stumble

Maryland’s appellate cases articulate the elements for negligent misrepresentation in a five-part sequence: (1) the defendant owed a duty of care to the plaintiff and negligently asserted a false statement; (2) the defendant intended that the statement would be acted upon; (3) the defendant knew the plaintiff would probably rely on it and that reliance, if the statement were erroneous, would cause loss or injury; (4) the plaintiff justifiably relied and took action; and (5) the plaintiff suffered damages proximately caused by the negligence.

In professional services disputes, the duty element is often the sticking point due to Maryland’s economic-loss controls. The plaintiff often argues “intimate nexus” (contractual privity or equivalent) or a Restatement § 552-like “information supplied for guidance” theory; the defense argues the opposite: no privity-equivalent relationship, no limited class of intended reliance, and therefore no duty.

Evidence that tends to satisfy duty and intent-to-influence relies on the paper trail: proposals and SOWs, status reports, formal certifications, compliance representations, stamped plans, RFP/RFQ responses, bid documents, and communications showing the author understood the audience and purpose. In contrast, generalized marketing statements or puffery are easier to defend.

Reliance is the second most frequent battleground. Plaintiffs must show they changed position as a result of the statement (e.g., proceeded with procurement, approved a change order, refrained from mitigation, released retainage, or waived inspection rights). Defendants often argue the plaintiff relied on its own due diligence, contractual risk allocation, or independent expert review.

Fraud: elements, burden of proof, and the reliance trap

Maryland requires fraud to be proven by clear and convincing evidence. The elements typically include: (1) false representation; (2) knowledge of falsity or reckless indifference; (3) intent to defraud; (4) reliance and right to rely; and (5) compensable injury.

In practice, a fraud claim changes the settlement posture because, if proven, it can support punitive damages in appropriate cases (subject to Maryland’s stringent “actual malice” standard). Maryland’s punitive-damages jurisprudence ties punitive damages to actual malice and distinguishes fraud from negligence-based misrepresentation (where punitive damages are generally not available).

The reliance trap is real. Maryland’s decisions emphasize that fraud ordinarily requires personal reliance by the plaintiff; attenuated “third-party reliance” theories are often rejected. Thus, plaintiffs must connect the defendant’s falsehood to their decision-making, not merely to a regulator’s, lender’s, or other intermediary’s decisions (absent a recognized exception).

Concealment and non-disclosure: when silence becomes actionable

Maryland recognizes fraud by concealment in limited circumstances. At baseline, “mere silence” is not actionable fraud without a duty to speak; but concealment can be actionable when the defendant’s conduct amounts to suppression of truth through misleading talk, acts, partial disclosures, or distraction from real facts.

For professionals and service providers, concealment exposure often arises in project communications: reporting that a deliverable is “on track” while withholding that a key assumption failed, disclosing a test result without revealing a known limitation, or describing compliance status while omitting a nonconformity. In litigation, the duty-to-disclose analysis often relies on relationship signals (fiduciary/confidential relationships, superior knowledge, partial disclosures, statutory duties, or situations where the defendant knows the other side is acting under a mistaken assumption that the defendant helped create).

Maryland also has a statutory “fraudulent concealment” tolling rule—separate from substantive concealment as a tort—that can affect limitations defenses: if the adverse party’s fraud kept the plaintiff from knowing the cause of action, accrual is deferred until discovery (actual or constructive).

Professional negligence: duty, standard of care, causation, and proof mechanics

Professional negligence is negligence with a professional standard-of-care overlay. In any negligence claim, duty, breach, causation, and damages remain the core structure. Maryland’s jurisprudence defines proximate cause as including both causation-in-fact and legal causation, and it frames foreseeability as part of legal causation analysis.

In cases against licensed design professionals and similar regulated “licensed professionals,” Maryland imposes a procedural proof-gatekeeping requirement: within defined parameters, plaintiffs must file a certificate from a qualified expert attesting that the licensed professional failed to meet an applicable standard of professional care, subject to waiver/modification in some circumstances. Failure can trigger dismissal without prejudice.

This matters in Montgomery County because it forces early expert engagement and narrows the tactical space for placeholder pleadings. Even if a plaintiff labels the count “breach of contract,” defendants may argue that the “gravamen” is negligent rendering of services within the license scope—thereby triggering certificate requirements. Maryland appellate decisions reflect that this statute can be litigated hard at the motion-to-dismiss stage.

Table comparing elements and proof burdens

| Claim theory | Core elements (Maryland) | Burden / special proof points | Typical evidence in consultant/contractor/provider disputes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negligent misrepresentation | Duty + negligent false statement; intent/knowledge of likely reliance; justifiable reliance; proximate damages. | Preponderance; duty especially contested for pure economic loss. | Engagement letter/SOW; representations in reports, submittals, status emails; reliance actions (approvals, payments, waivers). |

| Fraud / fraudulent misrepresentation (incl. fraudulent inducement) | False representation; scienter (knowledge/reckless indifference); intent to defraud; reliance/right to rely; damages. | Clear & convincing evidence. Reliance commonly attacked; punitive damages require stringent showings/actual malice framework. | Pre-contract communications; “capability” claims; concealment of conflicts; internal documents showing knowledge; proof plaintiff acted because of the lie. |

| Fraudulent concealment / non-disclosure (substantive tort) | A duty to disclose; concealment or partial disclosure; intent to defraud/deceive; reliance; damages. | Clear & convincing for fraud-based theories; duty-to-disclose is decisive. | Partial disclosures; omitted defect reports; withheld nonconformity; change-condition knowledge; meeting minutes where issues were intentionally not disclosed. |

| Professional negligence (regulated licensed professionals) | Negligence elements with professional standard of care; often requires expert framing. | Certificate of qualified expert may be required (CJP §§ 3-2C-01–02). | Expert certificate; licensing scope proof; standards (industry/custom, codes); causation on costs/delay/rework. |

| Maryland Consumer Protection Act (consumer-facing services) | Prohibited practice (false statement, omission, knowing concealment, etc.) + injury/loss as result; possible fee shifting if damages awarded. | Statutory; consumer-transaction scope often litigated; intent required for some subsections. | Advertising/representations; invoices; disclosures; proof consumer reliance and loss; attorney’s fees records if awarded. |

Chapter 3: When contractual breaches become torts

In commercial litigation, “when does breach become tort?” is less about labels and more about what duty is allegedly breached and how the injury happened. I approach the conversion question through three practical gates: (1) independent duty, (2) character of the wrongful conduct, and (3) the economic-loss constraint.

Independent duty: separating “nonperformance” from “misconduct.”

Maryland’s baseline rule is that a breach of contract does not automatically constitute a tort. That baseline protects contract risk allocation, including negotiated limitations and remedies. Courts cite the settled principle that “not every duty assumed by contract will sustain an action sounding in tort,” and they watch for attempts to repackage a broken promise as negligence.

An “independent duty” can arise from several sources relevant to consultants, contractors, and service providers:

First, duties imposed by law on certain industries or roles. For example, Maryland’s treatment of negligent misrepresentation recognizes tort duties to provide information for others’ guidance, particularly when the provider understands the purpose and audience.

Second, duties created by special relationships—fiduciary or confidential relationships—where reliance may be differently analyzed and where nondisclosure obligations can be stronger. Maryland’s concealment jurisprudence repeatedly signals that “mere silence” is not enough, but that the analysis changes when a duty to speak exists or when a partial disclosure becomes misleading.

Third, statutory duties. In consumer-facing service disputes, the Maryland Consumer Protection Act expressly targets misrepresentation and knowing concealment in connection with the sale or performance of consumer services, thereby imposing statutory liability beyond contract.

Character of conduct: affirmative misrepresentation, half-truths, and interference with mitigation

In my practice, courts are more receptive to tort theories when the defendant’s conduct is affirmatively deceptive rather than merely incompetent. Maryland fraud cases describe the scienter requirement as actual knowledge or “reckless indifference” to truth, and they caution that negligence—even “gross” misjudgment—does not satisfy fraud’s knowledge element.

For concealment, Maryland’s language on partial disclosures is the key. If a party makes a statement that is incomplete and misleading, the law may treat it as actionable concealment. This is where professional disputes often “tortify”: (a) a contractor reports “substantial completion” while withholding known critical defects; (b) a consultant certifies that a system meets requirements while omitting a known exception; (c) a service provider reports that compliance is achieved while hiding a failed audit item. Maryland opinions repeatedly recognize that “suppression of the truth” can constitute fraud, and that half-truths can shift the analysis.

Fraud in the inducement is a particularly common pathway: the alleged lie occurs before the contract exists, so the plaintiff argues the tort arises from pre-contract deception rather than performance failure. Maryland decisions treat fraudulent inducement as a theory of committing fraud with the same essential elements.

But Maryland courts also caution against inferring fraudulent intent merely from breach. Where the “fraud” allegation is simply that a defendant promised future performance and later failed, courts look for additional evidence of intent not to perform at the time of the promise. Maryland appellate decisions discussing builder disputes illustrate the risk of drawing the fraud inference solely from nonperformance.

The economic loss doctrine as a gatekeeper

In many professional disputes, damages are purely economic: delay costs, rework costs, lost profits, lost business value, cost to correct defective design, wasted fees. Maryland’s economic loss doctrine is the defense’s primary tool to argue “contract-only.” The doctrine reflects judicial reluctance to extend tort liability for economic loss absent contractual privity (or privity-equivalent conditions) when there is no physical injury or risk of severe physical injury/death.

The construction context is illustrative. Maryland’s high court has acknowledged that jurisdictions are split, but it emphasized that construction is governed by a network of contracts that defines risks, duties, and remedies—supporting the argument that economic loss should remain in contract.

Still, misrepresentation claims can survive if structured correctly. Maryland’s negligent misrepresentation doctrine expressly contemplates economic loss (pecuniary damages), and cases recognize that personal physical injury is not required for negligent misrepresentation recovery.

Chapter 4: Montgomery County specifics

Montgomery County practice shapes how these theories are litigated, even though the underlying tort doctrines are statewide. In Montgomery County, the key practical overlays are (1) docket management through Differentiated Case Management (DCM) tracks, (2) the Maryland Business & Technology Case Management Program (BTCMP) presence and its published nonprecedential opinions, (3) ADR infrastructure, and (4) procedural gatekeeping statutes (certificates of qualified expert) that are often litigated early.

DCM: early classification and the tempo of litigation

The Circuit Court’s DCM system is designed to manage cases through early intervention, ongoing control, and tracking of assignments that drive scheduling and time standards. The Montgomery County Civil DCM Manual describes the plan’s goal as structured case management with meaningful pretrial events and sufficient preparation time.

In practice, the DCM track assignment affects how fast a tort-tinged contract case reaches key events: initial scheduling, early motions, expert deadlines, settlement conferences, and trial windows. For plaintiffs trying to transform a case into fraud or negligent misrepresentation, tempo matters because reliance and causation often require third-party discovery, expert modeling, and document-intensive reconstruction. For defendants, early track tempo can be an advantage: file a motion to dismiss or summary judgment before discovery expands.

Business & Technology cases: why they matter in Montgomery County

Maryland’s BTCMP is established under Maryland Rule 16-308 to enable circuit courts to handle business and technology matters in a coordinated and efficient way.

Montgomery County is prominent in BTCMP postings. The Maryland Courts BTCMP “Published Opinions” page lists numerous Circuit Court for Montgomery County decisions and makes clear that these trial court opinions are not precedent, even though they may carry analytical value.

This is directly relevant when evaluating how “contract” disputes evolve into tort claims in Montgomery County, because BTCMP disputes often involve:

- complex commercial engagements (consultants, technology vendors, financial services),

- information asymmetry and reliance dynamics,

- and high-stakes economic loss computations.

A concrete example appears in a Montgomery County BTCMP opinion addressing motions to dismiss misrepresentation counts: the court treated an “intentional misrepresentation” count as duplicative of a fraud count, but allowed a negligent misrepresentation count to proceed where facts and reliance were sufficiently pleaded.

That local trial-level reasoning tracks statewide doctrine: courts are skeptical of redundant tort counts but will let negligent misrepresentation proceed where the complaint plausibly pleads false statements, reliance, and damages within a duty framework.

ADR and mediation: practical effects on tort/contract pleadings

Montgomery County’s Circuit Court ADR program references mediation under Maryland Rule 17-208 and publishes court-designated mediator rates by track, indicating a structured system in which parties may be required to use court-designated mediators at set hourly rates based on case track.

This ADR structure has a subtle effect on pleading strategy: plaintiffs may plead tort claims (fraud, concealment) to enhance leverage going into mediation—especially where fee shifting (under consumer statutes) or punitive damages theories might be implicated—while defendants may move to narrow the case to contract to reduce perceived “exposure range.” The court’s mediation framework thus interacts with the substantive tort/contract boundary.

Certificate-of-qualified-expert gatekeeping in Montgomery County

For malpractice claims against licensed professionals, Maryland’s certificate-of-qualified-expert statute can be litigated early in any circuit court, including Montgomery County. The statute defines covered “claims” broadly to include actions against a licensed professional (or the entity through which the licensed professional performed services) based on alleged negligent acts/omissions in rendering professional services within the scope of the license.

Maryland’s high court has enforced this requirement in engineer malpractice cases, outlining dismissal consequences and limited waiver/modification options.

In Montgomery County construction/design disputes, this creates a front-loaded battleground. Plaintiffs must decide: do I allege professional negligence (triggering certificate requirements) or focus on misrepresentation/contract theories? Defendants, conversely, often evaluate whether a misrepresentation claim is “really” a professional negligence claim in disguise and whether a certificate-based dismissal motion is available.

Practical note on accessing Montgomery County trial reasoning

Montgomery County trial-level decisions are typically not precedential and not routinely published; when they are available on official sources, BTCMP postings are one of the most visible repositories. Maryland Courts explicitly notes that BTCMP opinions are not precedent, but they provide factual and legal analysis useful to judges and litigants.

Chapter 5: Practical guidance for consultants, contractors, and service providers

The goal for a sophisticated service provider operating in Maryland is not merely to “avoid negligence” in the abstract; it is to avoid the specific behaviors that courts treat as tort triggers: false statements, misleading partial disclosures, and concealment—especially when those statements induce reliance in economically significant decisions.

Risk management starts with the truthfulness architecture of the engagement

Because negligent misrepresentation and fraud theories often turn on “information supplied for guidance,” I treat the engagement as an information pipeline. Where does information originate? Who approves it? Who receives it? What qualifiers are attached? If a project manager’s weekly report is treated as “official,” it can become Exhibit A in a misrepresentation case.

Maryland’s negligent misrepresentation elements put reliance and intended influence at the center. Service providers should assume that formal communications can be treated as “intended to be acted upon,” particularly when the recipient’s next step is predictable (approve, pay, proceed, waive, accept).

For fraud and concealment, Maryland’s doctrine around half-truths is critical: if you say something partially, and the omission makes the statement misleading, courts may treat it as actionable concealment rather than harmless silence. This is why “carefully worded, technically true but misleading” updates are dangerous.

Contract drafting to reduce tort exposure without pretending it will eliminate it

No contract clause is a magic bullet against fraud, but robust drafting can reduce negligent misrepresentation and the appearance of reliance:

Integration clauses and allocation-of-risk provisions help reinforce that the parties intended contract to govern remedies, which aligns with the policy concern that contract duties should not automatically become tort duties.

Reliance disclaimers and “no third-party beneficiary/no third-party reliance” language are particularly important for consultants whose deliverables might be shared with lenders, investors, contractors, or regulators. Maryland’s third-party duty analysis in information-provider cases (e.g., the constrained approach articulated in accountant contexts) makes audience and intended reliance central. Use that: define the permitted reliance group and purpose; require written consent for reliance by others.

Limitation of liability and waiver of consequential damages still matter—especially because many “economic loss” items are consequential. But plaintiffs often plead tort to bypass those limits. The best defense is not a clause alone; it is making sure your project communications do not create the factual predicate for tort (false statements, concealment). Maryland’s warning that not every contract duty supports tort liability gives you doctrinal support, but facts can overwhelm doctrine.

Disclosure practice: “tell the whole truth or say nothing”

Given Maryland’s treatment of partial disclosures, I recommend a disciplined rule: when communicating about a sensitive issue (defect, failed test, schedule slip, compliance gap), either (a) provide a full, contextual disclosure with material qualifiers, or (b) explicitly state that the issue is under investigation and no conclusion is being communicated yet. This avoids half-truth exposure.

If you discover an error in previously provided information, remedial disclosure can reduce damages and reliance and strengthen defenses on causation. Maryland’s proximate-cause framework emphasizes both causation-in-fact and legal causation; intervening mitigation steps and corrective disclosures can matter.

Insurance alignment and documentation discipline

Misrepresentation and professional negligence claims can implicate different insurance towers (CGL vs. E&O/professional liability). While specific coverage depends on policy language, the strategic point is stable: the earlier you document and remediate issues, the easier it is to defend reliance and causation and to manage notice obligations.

In licensed-professional contexts, assume the certificate-of-qualified-expert statute will force expert scrutiny. Treat that as a risk-management cue: quality assurance, formal peer review, and deviation documentation are not just engineering best practice; they create defensible evidence when a certificate-backed negligence claim is filed.

Table of risk-mitigation steps mapped to the tort triggers

| Risk-mitigation step | Tort trigger addressed | Why it matters under Maryland doctrine |

|---|---|---|

| Define permitted reliance audience and purpose for reports/deliverables; prohibit third-party reliance without consent | Third-party duty and reliance expansion | Maryland’s duty analysis in information-provider cases turns on intended/known reliance and privity-equivalent limits. |

| Use “full-context” disclosures; avoid partial statements that omit key qualifiers | Concealment / half-truth liability | Maryland treats misleading partial disclosures as actionable concealment; mere silence differs from half-truths. |

| Maintain a contemporaneous decision log (assumptions, risks, client approvals) | Reliance and causation disputes | Helps prove what the client knew, what was approved, and whether reliance was justified. |

| Escalation protocol for discovered defects / nonconformities; documented corrective action | Fraud allegations and damages mitigation | Reduces scienter inference, supports lack-of-intent defenses, and narrows damages by enabling mitigation. |

| For licensed professionals, implement peer review and retain materials supporting standard-of-care compliance | Professional negligence + certificate exposure | A certificate-of-qualified-expert regime makes standard-of-care proof central and early. |

| Calibration of marketing claims; avoid unqualified “guarantees” inconsistent with actual capabilities | Fraudulent inducement allegations | Pre-contract statements can become inducement fraud theories; avoid overstatements that a jury can construe as factual representations. |

| Consumer-facing services: compliance review for CPA disclosures and advertising | Statutory deceptive practices | The CPA defines false statements, omissions, and knowing concealment as prohibited practices; fee exposure may follow. |

Chapter 6: Plaintiff and defense strategies

In Montgomery County commercial litigation, the real contest is not whether a plaintiff can cite the words “fraud” or “negligent misrepresentation”; it is whether the plaintiff can plead and prove duty, reliance, and loss within Maryland’s doctrinal boundaries—and whether the defense can cut tort away early to confine the case to contract remedies.

Plaintiff strategy: investigation and pleading that survives the “contract-only” attack

Plaintiffs should begin with an evidence-first investigation. Because negligent misrepresentation and fraud are statement-centered torts, the case lives or dies on identifying: (a) a specific statement or omission, (b) who said it, (c) when and why it was said, (d) what was false or misleading, and (e) the reliance decision it caused. Maryland decisions provide clear element lists for negligent misrepresentation and fraud, and plaintiffs should plead to those elements explicitly.

For fraud, the proof burden is higher—clear and convincing—and plaintiffs should plead facts that plausibly support scienter, not just nonperformance. Evidence of internal awareness, contradiction between internal reports and external statements, and repeated reassurances after discovering defects can help. Maryland decisions also caution against treating every broken promise as fraud; plaintiffs must show something beyond “he promised and failed.”

For concealment, plaintiffs must identify the duty-to-disclose pathway and explain why the omission was actionable (fiduciary relationship, partial disclosure, statutory duty, or other recognized duty source). Maryland’s half-truth doctrine is a strong tool where the defendant spoke but incompletely.

Plaintiffs must also confront the economic loss doctrine early. If damages are purely economic, the complaint should address duty explicitly—either through privity, privity-equivalent allegations, or an information-supplier duty theory that fits Maryland’s limits. Construction-related plaintiffs should be particularly careful, given Maryland’s treatment of economic loss in design-professional disputes on public projects.

If the defendant is a licensed professional and the core wrong is negligent professional services, plaintiffs must plan for certificate-of-qualified-expert obligations. Early expert engagement is non-negotiable in those cases; failure can lead to dismissal without prejudice and lost momentum.

Defense strategy: early narrowing through duty, duplication, reliance, and economic loss

Defense counsel’s first move is usually to reframe: “This is contract.” Maryland case law supports that not every assumption of duty in a contract creates a tort duty, and defendants can use that to challenge negligence counts as duplicative or legally insufficient.

The second move is duty. For negligent misrepresentation, duty is a required element; where damages are purely economic, defendants can invoke economic loss doctrine constraints and argue that privity-equivalent allegations are missing. Maryland’s construction-economic-loss reasoning (network of contracts) is strong in contractor/design-professional disputes.

The third move is reliance. Fraud and negligent misrepresentation both require reliance, and Maryland’s decisions reinforce that fraud ordinarily requires personal reliance. Defendants should identify alternative causal explanations: independent due diligence, contractual risk assumptions, third-party expert review, or plaintiff’s decision-making based on factors unrelated to defendant statements.

The fourth move is to attack fraud scienter and duplication. Where fraud is pleaded as a dressed-up breach (promise of performance later unfulfilled), Maryland appellate decisions caution against inferring fraud solely from breach and often scrutinize whether the fraud count is duplicative. Montgomery County BTCMP reasoning shows this pattern: striking an intentional misrepresentation count as duplicative of fraud while allowing negligent misrepresentation where pled facts support it.

In licensed-professional cases, the certificate-of-qualified-expert statute is an early dispositive weapon. Defendants should evaluate whether the claim falls within the statute’s defined “claim” scope and whether dismissal is available for noncompliance.

Experts, damages, and settlement considerations

In most professional negligence and misrepresentation cases involving economic loss, experts are central for at least one of three reasons:

One, to establish standard of care (especially for licensed professionals where certificate regimes effectively presuppose expert engagement).

Two, to model causation and quantify delay, rework, lost profits, or diminution in value under Maryland’s proximate-cause framework.

Three, to evaluate reliance reasonableness and industry custom (e.g., whether reliance on a report was justified in context).

Settlement posture differs depending on whether tort survives. Fraud introduces reputational risk and punitive-damages potential (though difficult to prove), while negligent misrepresentation introduces economic-loss recovery even without physical injury. Defendants often prefer to settle after tort counts are narrowed; plaintiffs often prefer settlement before those motions are decided. Maryland’s case law on proof burdens—clear and convincing for fraud—can be used in negotiation to calibrate risk.

In Montgomery County specifically, early ADR referrals and track-based scheduling can put meaningful settlement pressure on parties before full discovery maturity. The court’s ADR structure and published mediator rate information reinforce that mediation is a routine feature, not an outlier.

Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

Access Funding, LLC v. Linton, 478 Md. 111 (2022).

Balfour Beatty Infrastructure, Inc. v. Rummel Klepper & Kahl, LLP, 451 Md. 600 (2017).

Commercial Law Article § 13-301, Maryland Code (defining unfair, abusive, or deceptive trade practices).

Commercial Law Article § 13-408, Maryland Code (private action; attorney’s fees).

Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article § 3-2C-01, Maryland Code (definitions; malpractice claims against licensed professionals).

Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article § 3-2C-02, Maryland Code (certificate of qualified expert; dismissal; waiver/modification).

Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article § 5-101, Maryland Code (three-year limitations).

Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article § 5-108, Maryland Code (statute of repose for improvements to real property).

Courts and Judicial Proceedings Article § 5-203, Maryland Code (fraudulent concealment tolling).

Circuit Court for Montgomery County. (2017). Civil Differentiated Case Management (DCM) Manual.

Circuit Court for Montgomery County. (n.d.). Understanding DCM tracks.

Circuit Court for Montgomery County. (n.d.). ADR (mediation) information, including track-based mediator rates and references to Maryland Rule 17-208.

Cochran v. Norkunas, 398 Md. 1 (2007).

Ellerin v. Fairfax Savings, F.S.B., 337 Md. 216 (1995) (reported citation; posting note).

Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Albright, 433 Md. 303 (2013).

Frazier v. Castle Ford, Ltd., 430 Md. 144 (2013) (punitive damages principles in fraud context).

Heavenly Days Crematorium, LLC v. Harris, Smariga & Assocs., Inc., 433 Md. 558 (2013).

Hoffman v. Stamper, 385 Md. 1 (2005).

Lubore v. RPM Associates, Inc., 109 Md. App. 312 (1996) (as applied/quoted in later opinions).

Maryland Courts. (2022). Maryland Appellate Court Opinions page—name change effective December 14, 2022; precedential value unaffected.

Maryland Courts. (2022). Press release on renaming appellate courts (effective Dec. 14, 2022).

Maryland Courts. (2022). MDEC update on appellate court name changes and case numbering.

Maryland Courts. (n.d.). Maryland Business and Technology Case Management Program (BTCMP).

Maryland Courts. (n.d.). BTCMP published opinions listing; trial opinions not precedent.

Maryland State Bar Association. (2025). Maryland Civil Pattern Jury Instructions (5th ed., 2025 Update): Table of contents (including concealment/non-disclosure and professional liability chapters).

Mesmer v. Maryland Automobile Insurance Fund, 353 Md. 241 (1999).

Montgomery County Business & Technology Case Management Program trial opinion. (2007). In the Circuit Court for Montgomery County, Maryland (addressing dismissal of duplicative misrepresentation count and pleading sufficiency for negligent misrepresentation).

Swinson v. Lords Landing Village Condominium, 360 Md. 462 (2000).

Walpert, Smullian & Blumenthal, P.A. v. Katz, 361 Md. 645 (2000).