Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

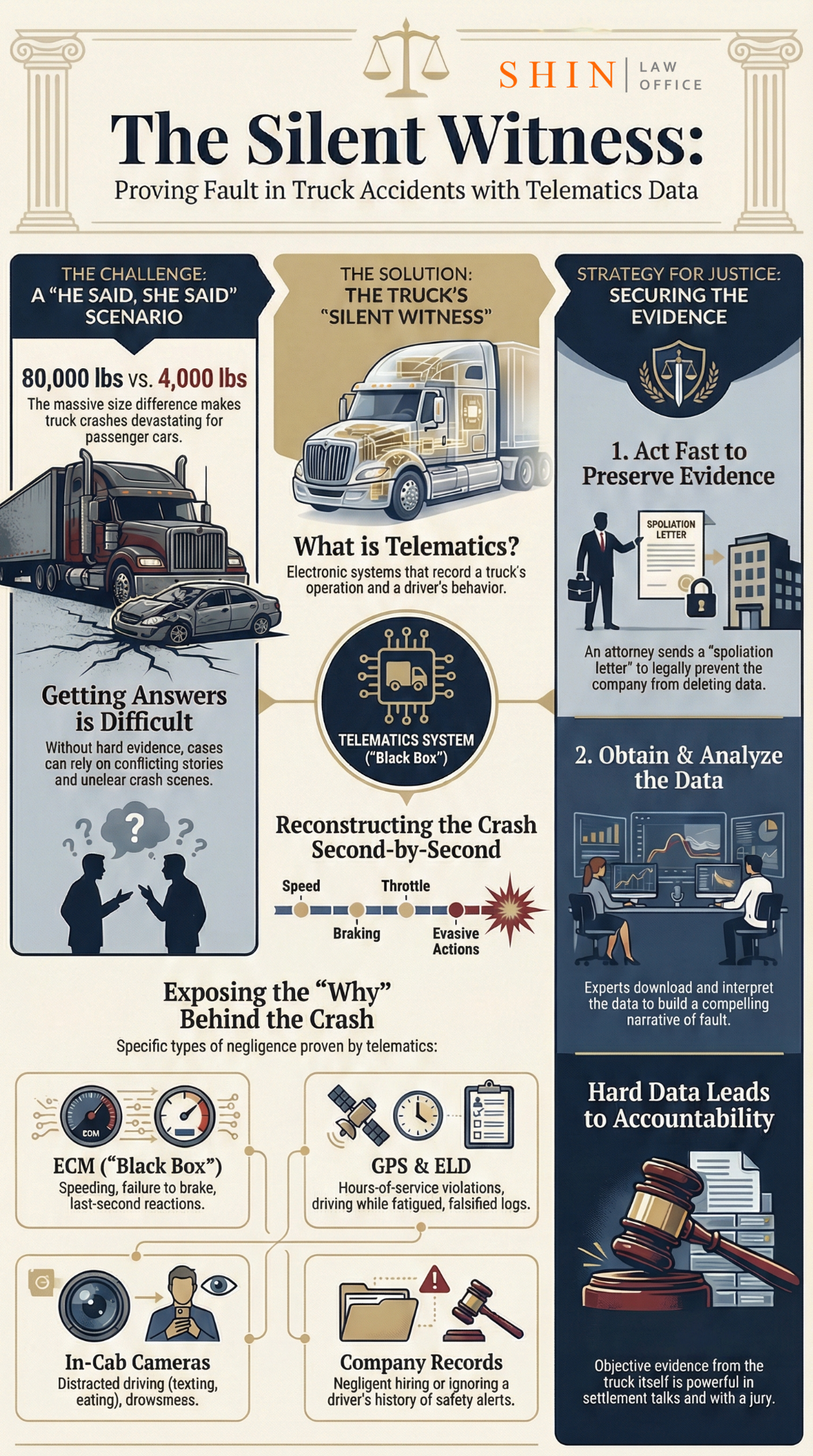

Telematics technology in modern 18-wheelers – including GPS trackers, electronic logging “black boxes,” and in-cab cameras – can provide crucial, objective evidence about a truck driver’s behavior before a crash. In a personal injury case involving a tractor-trailer collision, especially when the trucking company disputes liability, this data can be the key to proving that the truck driver (and their employer) were at fault. As a personal injury attorney, I have seen how telematics data can essentially put the jury “inside the cab,” revealing if the driver was speeding, distracted, or otherwise driving unsafely. Using this evidence, along with the driver’s history and the trucking company’s safety records, we can build a powerful case that not only tells what happened, but why it happened and who is responsible.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: The Devastating Reality of Truck Crashes and the Need for Answers

- Chapter 2: Telematics 101 – Black Boxes, GPS, and Cameras in Today’s Trucks

- Chapter 3: Reconstructing the Moments Before the Crash – What Was the Driver Doing?

- Chapter 4: Uncovering Company Negligence – Did the Employer Ignore the Red Flags?

- Chapter 5: Strategy for Justice – Preserving Telematics Evidence and Proving Fault

- Chapter 6: Conclusion – Using Telematics to Empower Your Case and Find Accountability

- References

Chapter 1: The Devastating Reality of Truck Crashes and the Need for Answers

When a commercial truck crashes into a passenger vehicle, the consequences are often catastrophic. The sheer size and weight difference – an 80,000-pound tractor-trailer versus a 4,000-pound car – means occupants of the smaller vehicle can suffer life-altering injuries or worse. If you or a loved one has been hurt in such an accident, I understand that you are likely overwhelmed. In these moments of tragedy, victims and their families desperately want answers. You want to know what exactly happened, why it happened, and who should be held accountable for the pain and loss you’re enduring.

For decades, getting those answers in a truck accident case was extremely difficult. A crash scene might give clues – skid marks, vehicle damage, eyewitness accounts – but piecing together the truth of what a truck driver was doing in the moments before the crash often felt like solving a puzzle with missing pieces. As your attorney, I don’t want you to rely on the truck driver’s story alone, especially when that driver (and their employer) might be trying to avoid responsibility. Fortunately, today we have a game-changer: telematics data. Modern commercial trucks are no longer simple machines; they are essentially rolling data centers. Every major trucking company now equips its fleet with sophisticated telematics systems that record nearly every aspect of a truck’s operation. This means that hidden in the truck’s electronics is a silent witness to the crash – one that doesn’t forget and doesn’t lie.

I speak from experience. I am Anthony I. Shin, Esq., a personal injury attorney who has handled serious truck accident cases in Northern Virginia, including Fairfax County, Loudoun County, Prince William County, Arlington County, Clarke County, and Frederick County. I have seen firsthand how telematics evidence can reconstruct a crash, expose driver negligence, and hold trucking companies accountable when they might otherwise hide the truth. In one recent case, for example, a truck driver who rear-ended my client tried to blame her for the crash. Her memory was foggy from a head injury, and without concrete evidence, it could have devolved into a “he said, she said” scenario. But the truck’s black box data told a very clear story that contradicted the driver’s excuses. It essentially put the jury in the cab of the truck, showing exactly how fast the truck was going and how the driver failed to brake in time. That objective evidence proved who was really at fault.

The Bottom Line Up Front is this: telematics data isn’t just technical jargon – it’s often the key to getting you answers and justice. In the chapters that follow, I will explain what telematics systems are and what kind of information they capture. I’ll then discuss how we use that information to uncover what the truck driver was doing (or not doing) before the crash. We’ll also look at the trucking company’s role – did they ignore warning signs of a dangerous driver? – and how that can affect your case. Finally, I’ll walk you through the legal strategy we use to obtain and leverage this evidence, including quick action to preserve data and the use of experts to present a compelling story to the jury. My goal is that by the end, you’ll not only understand the process, but also feel empowered: you’ll see that even when the defense tries to dispute liability, there is a path to the truth and a way to hold the right people accountable.

Chapter 2: Telematics 101 – Black Boxes, GPS, and Cameras in Today’s Trucks

To understand how we get answers from inside the truck, you first need to know about the technology that most big rigs have onboard. “Telematics” is a broad term that covers the electronic systems trucking companies use to monitor and record data from their vehicles. Let’s break down the main components of a typical 18-wheeler’s telematics system:

- Engine Control Module (ECM) – The Truck’s “Black Box”: Much like an airplane’s black box, most commercial trucks have an event data recorder in the engine’s computer. The ECM continuously monitors the truck’s engine and performance. When a “critical event” occurs – such as a sudden deceleration, crash, or airbag deployment – the ECM automatically freezes data from the moments leading up to that event. This data usually includes the truck’s speed, acceleration or braking patterns, engine RPM, throttle position, and brake application status in the seconds before impact. In other words, the ECM can give a second-by-second timeline of exactly what the driver was doing with the truck’s controls before the crash. If the driver claims, “I hit the brakes as soon as I saw danger,” the black box might confirm or contradict that – for example, it might show that the throttle was at 100% and the brakes at 0% right up until the collision, proving the driver never actually braked at all. Or if the driver says “I wasn’t speeding,” the ECM data could reveal the engine’s RPMs corresponding to a much higher speed – proving the truck was going, say, 80 mph when the speed limit (and the driver’s story) said 65. This kind of hard data can cut through any self-serving stories and give us scientific evidence of the truck’s operation.

- GPS Tracking and Speed Monitors: Almost all trucking fleets use GPS tracking devices. These record the truck’s location, route, and often its speed in real time. GPS data can help determine exactly where the crash occurred and the truck’s travel path. Importantly, many GPS-based systems also log speed over time. I’ve had cases where the GPS records showed a truck was consistently going 10-15 mph over the limit in the minutes leading up to the crash – invaluable evidence to demonstrate a pattern of speeding. Some systems will even flag events such as hard braking, sudden acceleration, or speeding, sending immediate alerts to the trucking company’s safety managers. For instance, if a driver slams on the brakes or takes a curve too fast, the system notes the time and magnitude of that event. All of this can be downloaded later to piece together how the driver was driving on that day.

- Electronic Logging Device (ELD): Federal regulations require commercial truck drivers to log their hours of service electronically now. The ELD is connected to the engine and automatically records when the truck is moving, for how long, and when it stops. The purpose of ELDs is to enforce hours-of-service rules (to prevent fatigued driving). But an ELD can also serve as evidence in a crash case: it can show whether the driver was operating beyond the legal hours (i.e., driving while dangerously fatigued), or whether they falsely logged off-duty while still driving. In one investigation, we compared a truck’s ELD data to the driver’s manual logs and found he had been on the road far longer than allowed – he was driving while logged as “Off Duty.” This not only showed the driver was likely fatigued at the time of the crash, but also that he was violating federal law, and the trucking company had failed to catch it. Evidence like that can even support claims of gross negligence, because it suggests a willful disregard for safety by both the driver and the company.

- In-Cab Camera Systems (Dashcams and Driver-Facing Cameras): Many modern trucks now have video recording systems. There may be a forward-facing dashcam that captures the road ahead, and often a driver-facing camera that watches the driver. These cameras are often part of advanced safety systems. They can be triggered by certain events (such as a hard brake or a collision) to save a video clip. Some systems are even “smart” cameras with AI: they actively monitor for signs of distracted driving or other unsafe behaviors. For example, an AI-equipped system can detect if a driver’s eyes are off the road or if the driver is holding a phone or eating. If it detects such behavior, it will immediately trigger an alert and record video of the incident. Trucking companies can be notified in real time when a driver is texting, not wearing a seatbelt, drowsy, eating, using a cellphone, speeding, or braking harshly, among other things. Imagine a scenario: a truck’s inward-facing camera records the driver looking down at his phone for 5 seconds right before he rear-ends someone. That video, if available, is powerful, direct evidence of distraction. In fact, there was a case in the U.K. where a truck driver was caught on his dashcam texting moments before a crash – the footage showed unequivocally that he was looking at his phone instead of the road, and he was later criminally prosecuted. A police investigator commented that it was “fortunate that the company had installed cameras… which allowed us to examine the driver’s actions”. For our civil injury case, a dashcam or in-cab video can be equally game-changing, showing the jury exactly what happened inside the cab.

- Additional Sensors and Alerts: Beyond these major components, trucks may have additional safety sensors, such as collision-avoidance systems, lane-departure warnings, and adaptive cruise control. These can also produce data (such as how many collision warnings went off that day, or whether the driver reacted to them). Some fleet systems create a “driver scorecard” aggregating all the data – factors like overspeed events, harsh braking, seatbelt use, etc. If we obtain those records, we might see that the company had been scoring that driver poorly on safety metrics for months but didn’t intervene.

In summary, today’s trucks carry a wealth of electronic information. This telematics data can provide a moment-by-moment account of the truck’s operation and the driver’s behavior. It is far more detailed and reliable than any eyewitness. I often call the truck’s black box or computer systems “the only witness that cannot lie,” because unlike humans, they don’t have faulty memories or incentives to cover up the truth. In the next chapter, we’ll see how we leverage this digital evidence to reconstruct what happened and answer the critical question: What was the truck driver doing (or failing to do) right before the crash?

Chapter 3: Reconstructing the Moments Before the Crash – What Was the Driver Doing?

One of the most important questions for any accident victim is: “What was the truck driver doing just before the crash?” Was he paying attention to the road, or was he distracted by something? Was he driving responsibly, or was he speeding, tailgating, or driving erratically? Thanks to telematics, we can often answer these questions with a high degree of certainty. We essentially use the truck’s own data to reconstruct the driver’s actions and the vehicle’s movements in those crucial seconds (or minutes) leading up to the collision.

Let me break down how we do this, using the various telematics components discussed:

- Speeding and Braking Patterns: We gather data on the truck’s speed over time from the ECM and GPS. If the crash was a rear-end collision, for example, a key question is whether the truck driver was going too fast or failed to slow down in time. Telematics data can show if the truck was speeding immediately before the crash. It can also show exactly when the driver applied the brakes and how hard. In one case I handled, the truck’s black box revealed a “hard brake event” only half a second before impact. In practical terms, that meant the driver wasn’t paying attention until it was too late – a responsible driver who was keeping a proper lookout would have started braking much sooner when traffic stopped ahead. That single data point completely undercut the defense’s argument that “the accident was unavoidable”; instead, it proved the crash happened because the driver was not keeping a safe distance and only reacted at the last instant. We’ve also had cases where the data showed no braking at all before the collision, which often indicates the driver never saw the danger in time, likely due to distraction or fatigue.

- Driver Inputs – Throttle and Steering: The ECM data can reveal whether the driver tried to accelerate or turn just before the crash. For example, if the driver claims “I tried to swerve and avoid the collision,” the data might show a sharp steering input (if the truck has a steering angle sensor) or not. If there’s no sign of evasive action in the data, it suggests the driver either didn’t see the hazard or froze up. Similarly, throttle data tells us if the driver inexplicably hit the gas instead of the brake, or kept cruising without slowing. I once reviewed ECM data from a crash that showed the truck was at nearly full throttle until 1 second before impact – clearly disproving the driver’s claim that he had slowed down when traffic ahead stopped.

- Evidence of Distracted Driving: This is a big one. Distraction can come in many forms – texting, talking on the phone, eating, adjusting the GPS, or even just daydreaming and not watching the road. How can we prove a driver was distracted? Telematics helps in both direct and indirect ways. Direct evidence comes from in-cab cameras if available: footage might show the driver looking down at a cellphone or reaching for something. Not every truck has a driver-facing camera, but when they do, and we get the footage, it can be the smoking gun. For instance, as mentioned earlier, dashcam footage in a known case showed a truck driver was texting while driving just before a crash, and that objective video helped establish clear negligence. But even without video, telematics provides indirect evidence of distraction. If the data shows, for example, that the truck maintained highway speed and never decelerated until the moment of impact, it implies the driver wasn’t looking at the road (because a reasonably attentive driver would have seen traffic slowing or an obstacle and at least started to brake). Or consider a scenario reflected in the data: the driver was on cruise control and didn’t brake until a split-second before the crash – that often tells us he was “on autopilot” mentally, not actively monitoring the road. We might also see patterns like constant drifting and corrections if the truck has lane-departure sensors, suggesting the driver was possibly drowsy or distracted over time. Additionally, we often pair telematics data with cellphone records (obtained through legal discovery) to determine whether the driver was on a call or texting at the time of the crash. The combination of phone records and, say, a sudden absence of braking in the data can strongly point to distraction.

- Driver Fatigue and Hours-of-Service Violations: A distracted driver is dangerous, but a fatigued driver is, too. Long-haul truckers are required by law to take rest breaks and not exceed certain daily driving hours because driving while tired can be as impairing as drunk driving. If we suspect fatigue was a factor (for example, the crash happened late at night or the driver’s log shows a very long shift), we will scrutinize the ELD and log data. I recall a case where the ELD data proved the driver had been behind the wheel for far longer than federal law allows – he was effectively driving while exhausted. Shortly before the crash, he had been on duty for over 14 hours. The telematics evidence of this violation helped us argue that his fatigue led to slower reaction times and poor judgment. It also opened the door to punitive damages because it showed a willful violation of safety regulations. Furthermore, if the ELD shows falsification (such as the driver logging himself as “resting” when he was still driving), it not only damages the driver’s credibility but also points to the trucking company’s oversight failures. In a recent federal case in Virginia, victims of a crash sued the trucking company for negligent hiring/retention partly because the driver had a history of serious safety violations, including incidents likely tied to fatigue or poor driving habits. The court recognized that if a company hires or keeps a trucker with a known record of unsafe driving, and that driver then causes a crash, the company can be held liable for negligence in addition to the driver’s liability.

- Other Unsafe Behaviors: Telematics can also capture behaviors such as hard cornering, failure to signal, or not wearing a seatbelt. These may be more minor details, but in some cases, they can contribute to the narrative of negligence. For example, if a truck took a turn too fast and tipped over onto your car, the accelerometer data or stability control data might show the exact g-forces and that the turn was taken at an excessive speed. Or if a truck driver ran a red light, the GPS and speed data might help prove he didn’t even attempt to slow for the intersection. Every piece of digital evidence helps fill in the timeline of what the driver did versus what a reasonably careful driver should have done.

Reconstructing the moments before a crash is like assembling a story from digital clues. By the time we finish analyzing the telematics, we often have a very clear picture of driver behavior: maybe it shows the driver was speeding, didn’t hit the brakes until the last instant, and was likely looking at his phone. Or it shows the driver had been on duty too long and was slow to react, drifting out of his lane. Whatever the specifics, this reconstruction is crucial. It turns a vague accident report (“vehicle A struck vehicle B”) into a compelling narrative of fault (“the truck driver, not paying attention and following too closely, failed to brake in time, causing the crash”). That narrative, backed by hard evidence, will resonate strongly with a jury.

Chapter 4: Uncovering Company Negligence – Did the Employer Ignore the Red Flags?

In truck accident cases, it’s not just the driver who may be at fault. The trucking company that employed the driver can also be held responsible, especially if it failed to act on warning signs or violated safety rules itself. As someone who has represented victims of trucking crashes, I always investigate the company’s role in the tragedy. Juries need to understand not only what the driver did wrong, but also whether the trucking company’s negligence contributed, for instance, by hiring an unqualified driver, not training them properly, or ignoring a pattern of dangerous behavior on the road.

Telematics data plays a big part in uncovering this broader picture of negligence. Here’s how we examine the company’s potential fault:

- Driver’s History of Unsafe Driving: One of the first questions I ask is, “Did this driver have a history of bad driving before this crash, and did the company know about it?” We request and review the driver’s employment file, training records, and any prior incident reports or telematics reports. Many trucking companies use their telematics systems to generate safety reports on drivers. If a driver has frequent alerts for hard braking, speeding, or distraction events, those should show up in the company’s records. We’ve seen situations where a driver had dozens of safety infractions recorded – like constant speeding violations or multiple instances of distracted driving captured on camera – yet the company kept sending them out on the road without extra training or discipline. If that’s the case, it may amount to negligent retention (the company’s failure to remove or retrain a risky driver). In a notable Virginia case, a truck driver who caused a serious crash had been fired from a previous job for “too many incidents” and safety violations documented in his record. The new employer (Western Express, Inc.) hired him anyway. After the crash, the victims sued not just for the driver’s negligence, but also claimed the company was negligent in hiring and retaining him, given his poor safety history. The court allowed those claims to go forward, recognizing that if proven, the company could indeed be held liable for putting such a driver behind the wheel of an 80,000-pound truck.

- Knowledge Through Technology – No “Ignorance” Excuse: With all the telematics tools available, trucking companies can monitor their drivers in real time. They can’t easily claim they had “no idea” a driver was being unsafe. For example, if a company has inward-facing cameras or an AI driver-monitoring system, they might receive instant notifications if a driver is caught on camera using a cellphone or failing to pay attention. Similarly, weekly or monthly telematics summaries might flag a driver based on metrics such as average speeding incidents per 100 miles. We often ask in depositions: “What do you do when you get an alert that your driver was speeding or driving distracted?” If the answer is “We talk to the driver” or “We have a coaching program”, we then dig into whether those steps were actually taken. If a company’s own system was flashing red flags about a driver and they essentially shrugged it off until a crash occurred, that is powerful evidence of the company’s negligence. It can support claims of negligent supervision or even willful disregard for safety. Juries tend to react strongly if we show, for instance, that the company received 10 separate alerts that their driver was using his phone behind the wheel in the month before the crash and yet did nothing – because that suggests the crash was not an isolated “accident” but a preventable disaster that the company failed to avert.

- Hiring and Training Practices: We also examine whether the company followed proper hiring protocols. Trucking companies are required to ensure their drivers are qualified and safe to operate big rigs. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSRs) impose a duty on carriers to only employ drivers who, “by reason of training or experience, can safely operate the type of motor vehicle” they will drive. This means checking a driver’s background, driving record, and certifications. If our case finds that the company ignored a poor driving record or a history of crashes when hiring the driver, that’s a breach of their duty. Additionally, we check if the driver was properly trained on the use of safety systems and company policies (for example, did the company have a policy against cell phone use while driving, and was the driver trained on it?). If not, that’s another mark against the company’s safety management.

- Hours of Service and Fatigue Management: Trucking companies must also ensure their drivers follow hours-of-service rules. If telematics or log data show that the driver was driving excessive hours or regularly violating the sleep/rest rules, we’ll ask: Did the company allow or even encourage this? Some companies, under pressure to deliver loads on time, create an environment where drivers feel they must push beyond legal limits. If we find emails or Qualcomm messages pressuring a driver to keep going, or if a company’s dispatch schedules virtually required breaking the rules, that’s evidence of systemic negligence. Moreover, the company is supposed to audit its drivers’ ELD logs periodically. If a driver repeatedly logged more hours than allowed or had unexplained gaps, and the company never addressed them, that can bolster a negligent supervision claim.

- Vehicle Maintenance and Telematics: Although this chapter focuses on the company’s knowledge of the driver’s behavior, it’s worth noting that telematics also records data about the truck’s performance that can implicate the company. For example, if the truck’s data shows chronic maintenance issues (maybe the brake sensor triggered alarms multiple times in weeks prior, indicating brake problems, but the company didn’t fix them), and then a brake failure contributed to the crash – that’s evidence of poor fleet maintenance. In one case, our inspection found that the truck’s brakes were practically worn out, and the telematics had logged several fault codes about brake pressure. The company had signed off on pre-trip inspections, saying everything was fine when it wasn’t. This turned a simple accident case into a story of corporate recklessness before the jury, highlighting that the company put a dangerous truck on the road. (I mention this because it often goes hand-in-hand with driver error – a safe company culture requires both safe drivers and safe vehicles.)

Ultimately, by “getting inside the cab” through telematics and company records, we often uncover a narrative that the trucking company either knew or should have known that this crash was likely to happen. Maybe they knew they had a habitually reckless driver and kept him on. Or they knew (or should have known) he was violating hours-of-service and turned a blind eye. Or they failed to enforce their own safety policies. This kind of evidence can be vital not only for securing compensation for you but also for potentially obtaining punitive damages if the conduct was egregious. More importantly to many victims, it’s about justice and prevention – holding the company accountable sends a message that safety cannot be ignored. If you’re suffering from a truck crash injury, you deserve to know if it resulted from a larger pattern of negligence, not just one driver’s bad day. Telematics helps us shine a light on that bigger picture.

Chapter 5: Strategy for Justice – Preserving Telematics Evidence and Proving Fault

Having all this technology and data available is wonderful, but it means nothing if we can’t obtain and preserve the evidence for your case. One of the biggest challenges in a truck accident investigation is ensuring that the crucial telematics data and recordings are not lost or erased. Unlike human memories, digital data can disappear – sometimes by accident, sometimes deliberately. In this chapter, I’ll outline the strategies I use to secure this evidence and how we deploy it to prove fault and persuade the jury.

- Acting Fast: The “Spoliation Letter” – The moment you hire me (or any truck accident attorney worth their salt), we will take immediate legal steps to preserve evidence. Trucking companies are only required by federal law to keep certain records (like ELD logs) for a limited time – often six months – and the truck’s black box data can be overwritten or lost if the truck gets repaired or put back into service. In fact, some critical ECM data might only be stored until it’s overwritten by new data, which could happen in a matter of weeks if the truck continues to operate. Trucking companies are very aware of this; many have rapid-response teams on standby for serious accidents, and one thing those teams do is secure the truck (and its data) for the company’s benefit. To counter this, we immediately send a legal notice, known as a spoliation letter. This letter formally instructs the trucking company to preserve all evidence related to the crash – including the truck’s ECM/black box data, the ELD logs, GPS data, dispatch communications, and any dashcam or in-cab camera footage. The spoliation letter puts them on notice that they must not delete or destroy this information. Once they receive that letter, they are legally obligated to keep everything. If they were to still “lose” or erase data after that, a court can sanction them severely. In fact, if a company were to destroy telematics data after being told to preserve it, I can ask the court to issue sanctions or even instruct the jury to infer that the destroyed evidence would have been unfavorable to the defense. This adverse inference can essentially tell the jury, “We don’t know exactly what the data would have shown, but you can assume it was so bad for the company that they decided to make it disappear.” Needless to say, no trucking company wants to be in that position, so a well-crafted spoliation letter is often very effective at protecting the evidence we need.

- Legal Discovery and Expert Analysis: After ensuring preservation, the next step is obtaining the data. We use the legal discovery process to request the truck’s telematics records. This can include formally asking for ECM download reports, ELD logs, GPS records, and any safety camera footage or alerts. Sometimes companies will comply and hand these over; other times, we need court orders or subpoenas, especially if some data is held by third parties (for example, some telematics info might be on a vendor’s cloud server). We also often demand the physical truck for inspection, when possible. I will bring in an accident reconstruction expert or a download technician to actually image the ECM (make a forensic copy of the black box data) and to verify everything. My team knows how to interpret the raw data, but having an expert engineer who can later testify is crucial. This expert can take the data – the speeds, brake applications, etc. – and create visuals for the jury, like charts or simulations. In one case, we used the black box data to create a computer animation of the truck’s approach to the collision, which powerfully showed the truck didn’t slow down at all until impact. The defense will have its own experts, of course, but when the data is on our side, it speaks louder than any opposing testimony.

- Overcoming Defense Tactics: It’s worth noting that the defense may sometimes dispute our interpretation of the data or try to exclude it. They might argue the data is incomplete, or the device wasn’t working correctly, or that a video is misleading without context. Part of my strategy is to preempt these arguments. We ensure the data was properly collected and preserved (chain of custody, etc.), and we often depose the company’s safety or telematics manager to confirm how the data was maintained. If there are gaps in the data, we ask why. For example, if the driver-facing camera “wasn’t recording” at the time of the crash, we will press for an explanation – did the driver cover it, was it disabled, or did the company conveniently not save that clip? A jury can find such explanations suspicious. In one federal case (unrelated to telematics, but illustrative), a court noted that if a key piece of evidence is missing, they examine whether there was a duty to preserve and a culpable mindset in its loss. If we suspect any foul play, we bring it up to the judge. But even without accusing anyone of intentional destruction, we make sure the jury hears about all available data. Digital evidence is considered objective, so jurors give it significant weight.

- Presenting the Evidence to a Jury: Once we have the telematics evidence, the final part of our strategy is using it effectively at trial (or in settlement negotiations). I always aim to translate the technical data into a compelling story. Instead of just throwing numbers at the jury, I’ll say something like: “The truck’s black box is like an unbiased witness that was riding along with the driver. Let’s hear what that witness has to say.” Then we show, for example, a timeline: 5 seconds before impact, the truck was at 65 mph, 4 seconds before – still 65, 3 seconds – 66 (perhaps even accelerating), 2 seconds finally brakes applied hard, 1 second – 45 mph, then collision. This timeline demonstrates visually that the driver had ample time but didn’t react until it was too late. If there’s a video, we will play the clip for the jury – nothing drives the point home more than seeing the driver’s eyes off the road or seeing the road view of a truck barreling forward without slowing. We complement this with any relevant company evidence: for instance, if the driver had prior safety violations, we might have a company safety officer on the stand admitting they knew about X number of incidents. By weaving the telematics data together with witness testimony and the plaintiff’s story, we create a full narrative: one that shows how the crash occurred and underscores the preventability of the tragedy. The goal is to leave no doubt in the jurors’ minds that this crash was not just bad luck or a minor mistake – it was the result of clear negligence by the driver and perhaps the company.

- Empowering Your Case, Even in Settlement: It’s worth noting that solid telematics evidence can often push the defense to settle and avoid trial. When we come to the negotiation table armed with printouts of the ECM data or video evidence of the driver’s behavior, the trucking company’s lawyers know that a jury would likely be swayed by that. I’ve had cases turn around entirely once we obtained the black box data – a trucking company that initially denied fault suddenly became very interested in discussing a fair settlement. In one situation, when confronted with the ECM report showing their driver had never hit the brakes, the defense essentially conceded liability, allowing us to focus on obtaining proper compensation for my client’s injuries without a protracted courtroom fight over fault.

In summary, the strategy for using telematics in a truck accident case boils down to: move quickly to preserve data, bring in the right experts to obtain and explain it, and seamlessly integrate the digital evidence into your case narrative. It’s a powerful combination of high-tech and legal savvy, all aimed at one thing – getting justice for you by revealing the truth of what happened.

Chapter 6: Conclusion – Using Telematics to Empower Your Case and Find Accountability

Truck accidents change lives in an instant. I have sat across the table from families who lost a breadwinner and from individuals who will never fully recover from their injuries. In those moments, hearing a trucking company’s defense lawyer say “We don’t believe it was our driver’s fault” can feel like a punch in the gut. But as we’ve explored, we are not helpless in the face of such denials. Telematics data empowers us to find the truth. It allows us to virtually climb into the cab of that 18-wheeler and see events through the eyes of an impartial digital witness.

By leveraging the truck’s black box, GPS records, electronic logs, and camera footage, we piece together a narrative that answers the vital questions: What was the driver doing? What was the driver not doing? And, could this crash have been avoided if proper care had been taken? Often, the answers to these questions reveal clear negligence – perhaps the driver was distracted and never even hit the brakes, or was exhausted after driving 14 hours straight, or was reckless from the start, speeding on a wet road. Just as important, telematics can uncover whether the company itself failed you: maybe they knew this driver had a problematic history, or they failed to maintain the truck’s safety, thereby putting everyone on the road in danger.

Standing up to trucking companies and their insurers can be daunting. They often have significant resources and will fight hard to avoid liability. But I find strength – and I hope you do too – in the knowledge that the data is on our side. Numbers don’t get intimidated, and videos don’t lie. When we present a case built on solid telematics evidence, we shift the power dynamic. It’s no longer just your word against the truck driver’s. It’s your word and the truck’s own data against the company’s excuses. And I can tell you, juries listen. In my experience, jurors care deeply about preventing future accidents. When they see that a truck’s black box or camera has captured dangerous behavior, they not only want to compensate the victim but also send a message to the trucking industry: do better, or face the consequences.

In closing, if you’ve been hurt in a collision with a large truck, I want you to know that the journey to justice is not one you need to take alone. As your attorney, I will use every tool at my disposal – especially the cutting-edge telematics technology – to get the proof we need. We will answer those pressing questions about what happened in that cab before the crash. We will hold the driver accountable for their actions (or inaction). And if the evidence shows the trucking company was negligent in hiring, training, or supervising that driver, we will hold them accountable too.

No piece of evidence can erase the pain of an injury or the loss of a loved one. But getting the truth can provide a sense of closure and validation. It can also ensure that you receive the financial compensation necessary to rebuild your life. Perhaps just as importantly, these cases push companies to improve safety – so that hopefully no other family has to go through what you are going through. Telematics data isn’t a magic bullet, but, as we’ve seen, it can certainly affect the outcome at trial and is often the deciding factor between a “he said, she said” stalemate and a clear victory for the injured. My promise to my clients is that I will leave no stone unturned and no byte of data unexplored in the pursuit of justice. By effectively getting “inside the cab” and uncovering the full story, we transform what might seem like an unwinnable case into a compelling fight for accountability – and together, we will strive to win that fight.

Principal Attorney | Shin Law Office

Call 571-445-6565 or book a consultation online today.

(This article is provided for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice. For advice on your specific situation, consult with a licensed Virginia attorney.)

References

- Byrne, R. E. (2025, December 12). How We Use Telematics Data to Win Truck Crash Cases. MartinWren, P.C. Blog.Hurston, N. (2022, March 7). Negligent hiring, retention claims survive motion to dismiss. Virginia Lawyers Weekly.Kinney, J. (2022, January 3). Truck Dash Cam Shows Distracted Driving Crash. GPS Trackit Blog.

Snellings Injury Law. (2026, January 22). Data Recorders Can Be the One Piece of Evidence That Make the Case. Snellings Law Blog.

Stolth, J. (2025, August 8). AI-Based Driver Behavior Monitoring System. Safe Fleet (Product page).

Paul v. Western Express, Inc., No. 6:20-cv-00051, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 50310 (W.D. Va. Mar. 21, 2022).