Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

Contracts are only as good as their formation. In Virginia, a contract isn’t enforceable unless it was formed with all the required legal elements and without factors that undermine its validity. This guide explains 20 common contract formation and validity disputes from lack of mutual assent and duress to fraud, mistakes, and more in plain English. Our goal is to help individuals and small business owners in Alexandria, VA, understand how contracts can fail before a breach ever happens. Each section provides a client-friendly explanation, a real-world example, key Virginia case law, and a quick takeaway. If you’re signing or enforcing a contract, knowing these concepts will empower you to avoid pitfalls and recognize when a contract may be void or voidable. Let’s dive in.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Lack of Mutual Assent (No Meeting of the Minds)

Chapter 2: Indefinite or Uncertain Terms

Chapter 3: Illusory Promises

Chapter 4: Lack of Consideration

Chapter 5: Duress (Coercion)

Chapter 6: Undue Influence

Chapter 7: Fraudulent Inducement

Chapter 8: Misrepresentation (Innocent or Negligent)

Chapter 9: Mutual Mistake

Chapter 10: Unilateral Mistake

Chapter 11: Unconscionability (Contracts of Adhesion)

Chapter 12: Illegality and Public Policy

Chapter 13: Statute of Frauds (Writing Requirement)

Chapter 14: Lack of Capacity – Minors

Chapter 15: Lack of Capacity – Mental Incompetence

Chapter 16: Lack of Capacity – Intoxication

Chapter 17: Lack of Authority (Agency Issues)

Chapter 18: Fraud in the Execution (Fraud in the Factum)

Chapter 19: Preliminary Negotiations vs. Binding Contract

Chapter 20: Void vs. Voidable Contracts and Ratification

References

Introduction

Contracts are the lifeblood of business deals and personal agreements. But not every agreement that appears to be a contract will hold up in court. In Virginia (as in most jurisdictions), a valid contract requires several key ingredients: offer, acceptance, mutual assent, consideration, capacity, and legality. If any of these ingredients are missing – or if certain harmful factors are present – the contract may be void (having no legal effect) or voidable (able to be canceled by one of the parties).

Formation and validity disputes arise when someone challenges a contract by saying, “This contract isn’t enforceable because something was wrong at the start.” Perhaps the parties never truly agreed on the same thing, or one party was misled or forced. Maybe one side lacked legal capacity, or the agreement was for an illegal purpose. These disputes often appear as defenses in breach of contract cases – for example, if you get sued for breach, you might argue that no valid contract existed to begin with. For individuals and small businesses, understanding these issues is crucial. It can help you avoid entering contracts that won’t hold up, and it can provide an “exit ramp” if you’ve been pulled into a bad deal.

In this series of chapters, we cover 20 types of contract formation or validity disputes common in Virginia. Each chapter breaks down the legal concept in client-friendly terms, provides a hypothetical scenario to illustrate the issue, cites Virginia law or cases (with Bluebook citations) that highlight how courts handle that issue, and ends with a takeaway. While we maintain a professional tone, we’ve avoided dense legalese to make these concepts approachable. Whether you’re a small business owner reviewing a contract or an individual wondering if an agreement you signed is enforceable, this guide will shed light on what can make or break a contract’s validity.

Let’s start at the beginning – with the most fundamental requirement of any contract: a “meeting of the minds.”

Chapter 1: Lack of Mutual Assent (No Meeting of the Minds)

Explanation (The Concept): A contract requires a true “meeting of the minds” – both parties must agree to the same terms at the same time. In plain language, if the parties did not actually agree on the key terms of the deal, there is no mutual assent, and thus no valid contract. Virginia courts use an objective standard to determine assent: they look at each party’s outward expressions (words, actions) to decide if a reasonable person would think an agreement was reached. Secret intentions or misunderstandings that aren’t communicated generally don’t count. As the famous Virginia case, Lucy v. Zehmer, taught, one party can’t claim “I was only joking” if their words and conduct reasonably led the other to believe the deal was serious. On the flip side, if it’s clear that the parties were talking about different things or never settled an essential term, a court may find no contract was ever formed.

Real-World Example: Imagine two small businesses in Alexandria negotiating over the sale of “100 chairs.” One business (the buyer) thinks they’re buying 100 office chairs for $5,000. The other business (the seller) believes the buyer is offering $5,000 for 100 dining chairs. They exchange emails and say “deal” – but each is thinking of a different product. When the truck arrives, the buyer is shocked to see dining chairs. Here, there was no true meeting of the minds on the fundamental subject of the sale. Each party misunderstood the terms of the agreement, so no valid contract was formed. If taken to court, a judge would likely find that mutual assent was lacking due to the latent ambiguity (hidden confusion) about what “chairs” meant.

Virginia Case Law: In Phillips v. Mazyck, the Virginia Supreme Court reaffirmed that “mutuality of assent – a meeting of the minds – is an essential element of all contracts”. If one party knows or should know that the other is mistaken about a deal, there is no true agreement. Similarly, the Virginia Court of Appeals noted that when parties intend to later sign a formal contract, there’s a strong presumption no binding deal exists until that happens. The key takeaway from the case law is this: courts will not enforce a supposed contract if the evidence shows the parties were talking past each other on critical terms or never intended to be bound at that stage.

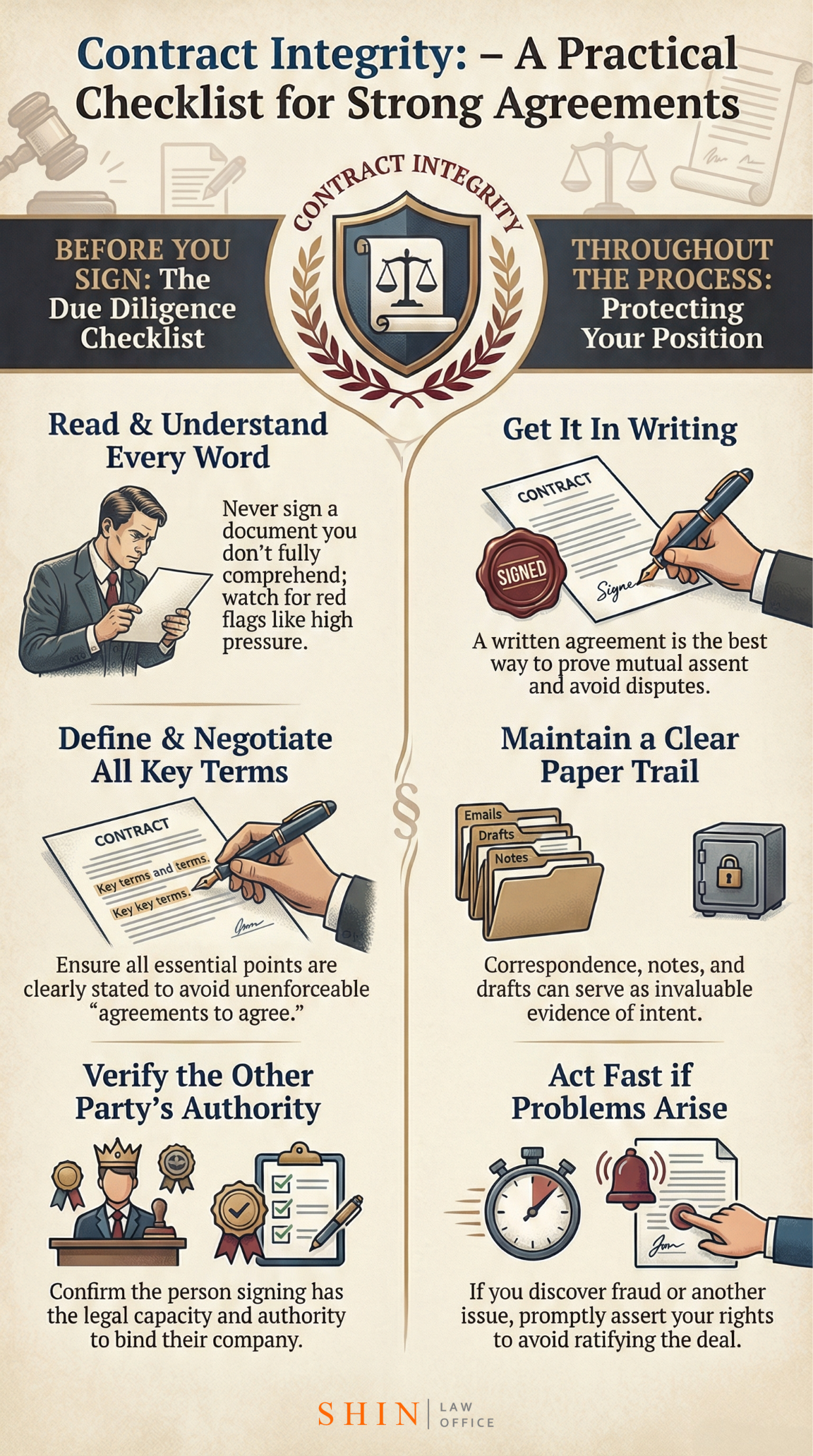

Takeaway: If both parties aren’t on the same page about a material term, no contract exists. Always confirm the key terms (who, what, how much, when) to ensure a real agreement – and get it in writing to avoid later “meeting of the minds” disputes.

Chapter 2: Indefinite or Uncertain Terms

Explanation: A contract must be reasonably definite and certain in its terms for a court to enforce it. If an agreement is so vague or incomplete that the court cannot figure out what was promised, it may be deemed unenforceable. In Virginia, an agreement that leaves critical points unspecified – like “We’ll agree on the price later” or “Services to be determined as we go” – might fail for indefiniteness. The logic is simple: if the parties themselves haven’t decided on the essential terms, there’s no way a court can enforce the “contract” because it’s unclear what to enforce. Virginia courts have held that, for example, an agreement for services must specify the nature and scope of the work, the key details of performance, and the compensation – otherwise it’s too indefinite to be a binding contract. While minor details can be left open or resolved by reasonable interpretation, the material terms (like subject matter, price, quantity, duration, etc.) generally cannot be so uncertain that one can’t tell what each side has to do.

Real-World Example: A freelance web designer and a local restaurant owner in Alexandria sign a letter saying, “Web Designer will create a website for Restaurant. Price to be negotiated later. Launch date to be determined.” They both sign it in a rush, thinking they’ll work out the details later. This “agreement” is likely too indefinite to enforce. What exactly will the web designer do (how many pages, what features)? What will the restaurant pay? By when must the work be done? None of that is clear. If a dispute arises – say the restaurant owner hires someone else and the designer claims breach of contract – a court would struggle to enforce such vague terms. The lack of certainty regarding essential terms (scope of work, timing, price) meant there was never a concrete, enforceable contract.

Virginia Case Law: The Virginia Supreme Court in Reid v. Boyle noted that a contract won’t be enforced if the obligations are not reasonably certain and definite. Citing an older case, the court explained that an agreement for services must be specific about the nature and extent of the service, the person to whom it’s rendered, and the compensation, or it will not be enforced. Likewise, in Moorman v. Blackstock, Inc., 276 Va. 64 (2008), the Court found no binding contract where material terms were left open and the parties anticipated signing a formal contract later. The legal rule is that courts won’t write the contract for you – if you leave major terms too indefinite, the contract can fail.

Takeaway: Nail down the essentials. If a deal’s key terms are vague or “to be determined later,” the agreement may be unenforceable. For a solid contract, be clear and specific about the important terms (who does what, when, how, for how much).

Chapter 3: Illusory Promises

Explanation: An illusory promise is a statement that looks like a promise but really isn’t because it leaves performance to the whim of the “promisor.” In a valid contract, each party must be bound to do something. If one party’s promise is so open-ended or discretionary that it doesn’t actually obligate them to anything, the contract fails for lack of mutual obligation (and usually lack of consideration, which we’ll cover next). Common examples include agreements where one side says, “I’ll do X if I feel like it,” or “I might buy this from you, but I’m not sure.” These aren’t real promises – they’re illusory. Virginia law treats illusory promises as no promise at all. The classic sign of an illusory promise is one party retaining an unfettered right to cancel or perform at their sole discretion without any restriction. Since that party isn’t actually committing to anything, the “contract” has no mutuality – only one side is truly bound.

Real-World Example: A small catering company tells a local farmer, “I might purchase 100 pounds of tomatoes from you next season for $2/pound, if business is good.” The farmer says, “Okay.” The word “might” is a red flag – the catering company isn’t firmly agreeing to buy anything; it’s leaving the decision entirely up to its own future wish. This is an illusory promise. Even though price and quantity are mentioned, the caterer hasn’t actually promised to buy – they’ve only said they might. If, later, the farmer tries to enforce this “agreement” because the caterer bought tomatoes elsewhere, a court would likely find no binding contract. The catering company’s “promise” is illusory, meaning no mutual obligation existed.

Virginia Perspective: Virginia courts emphasize that a contract must impose obligations on both parties. For instance, if a contract says one party “may cancel at any time for any reason,” that party’s promise may be illusory because they aren’t really obligated to perform. The Virginia Business Litigation Blog explains that such contracts “give the appearance of an obligation but when interpreted strictly create no enforceable obligation”. One example given: telling someone “I might sell you my car for $5,000” – you’re not actually committing to sell, so the other person can’t enforce it. Virginia case law often overlaps illusory promises with lack of consideration: since the illusory promisor offers nothing of substance (they can back out at will), there’s essentially no consideration for the other party’s promise.

Takeaway: A one-sided “promise” is no promise at all. If one party can walk away at their sole discretion without consequence, the agreement isn’t binding. Ensure that both sides have some firm obligation; otherwise, you don’t have a true contract.

Chapter 4: Lack of Consideration

Explanation: Consideration is the price or value each party exchanges in a contract – it’s often described as the “bargained-for exchange.” In everyday terms, each party must give up something or promise something of value for a contract to be enforceable. If an agreement lacks consideration, it’s essentially a gift promise, not a contract. For example, if I promise to give you $100 with nothing expected in return, you can’t sue me for breach if I change my mind – there’s no consideration from your side. Virginia defines consideration as a benefit to the promisor or a detriment to the promisee; each party must incur a legal benefit or a detriment as the price of the promise. Common scenarios of no consideration include purely one-sided promises, past actions (actions taken before the promise was made), or obligations one party is already legally required to perform (pre-existing duties). Without consideration, a contract is void and unenforceable.

Real-World Example: An Alexandria entrepreneur says to her friend, “You’ve been a great help. I’ll pay you $5,000 at the end of the year.” The friend hasn’t promised or done anything in exchange – it’s just a generous promise. At year’s end, the entrepreneur decides not to pay. Can the friend enforce this promise? Probably not. There’s no consideration given by the friend – no reciprocal obligation or detriment. The $5,000 promise was essentially a proposed gift. In contract law, a naked promise to make a gift is not binding absent consideration. Now, if the friend had agreed to perform consulting work for $5,000, that would be different (then each side would have consideration). But as it stands, the entrepreneur’s promise is unenforceable because the friend didn’t bargain or provide anything in exchange.

Virginia Law: The Virginia Supreme Court in Smith v. Mountjoy, 280 Va. 46 (2010), stated that consideration is “the price bargained for and paid for a promise”. It can benefit one party or harm the other. In GSHH-Richmond, Inc. v. Imperial Assocs., 253 Va. 98 (1997), the court reiterated that if what appears to be a contract lacks consideration, it’s essentially a gift promise and not enforceable. One party doing all the giving and the other doing all the getting does not make a contract – both must contribute something (money, service, a forbearance of a right, etc.). Virginia courts will void gratuitous agreements. For example, if someone tries to enforce a promise where they gave nothing in return, the court will say there’s no contract because of lack of consideration.

Takeaway: No exchange = no contract. Ensure both parties provide something of value. A promise to give a gift or do something for nothing in return, while morally binding, is not legally binding in contract law.

Chapter 5: Duress (Coercion)

Explanation: Duress in contract law means one party was forced into the agreement by wrongful pressure or threats. If you sign a contract under duress, it’s not a product of your free will, so the contract is voidable (you can later avoid it). Virginia recognizes both physical duress (e.g., threats of violence) and economic duress (e.g., wrongful financial threats that leave no reasonable alternative) as grounds to void a contract. The essence of duress is that one side’s will is overborne – they only agreed because they were presented with a “gun to the head” (literal or metaphorical). Courts generally look for three elements: (1) one party involuntarily accepted the terms, (2) circumstances left no reasonable alternative, and (3) those circumstances were the result of the other party’s coercive acts. A common example of economic duress: one party deliberately withholds something they owe or threatens a breach unless the other side agrees to new terms (sometimes called a “hold-up”). If proven, duress makes the contract voidable by the victim, because true consent was lacking.

Real-World Example: A small manufacturing business in Northern Virginia desperately needs a piece of equipment to fulfill orders. The supplier, knowing this, says, “Unless you sign a new contract to pay 50% more, I won’t deliver the machine – and you’ll lose your clients.” Facing ruin, the business signs the new contract. This is a classic economic duress scenario. The manufacturer didn’t freely agree; they were effectively forced by an improper threat (the supplier’s breach of the original deal) and had no practical alternative (losing customers could be catastrophic). In court, the manufacturer could argue the higher-price contract is voidable due to duress. Virginia courts have noted that duress can be “the unlawful presentation of a choice between comparative evils” – like the loss of property or compliance with an unjust demand.

Virginia Case Law: Vick v. Siegel, 191 Va. 731 (1951) is a leading Virginia case on duress, stating: “To constitute duress, it is sufficient if the mind is constrained by the unlawful presentation of a choice between comparative evils”. In other words, if someone’s only options are to suffer a serious harm (e.g., financial ruin, loss of property) or to sign the contract, and that situation was unlawfully imposed by the other party, duress exists. Virginia courts require that the pressure be wrongful – using legitimate hard bargaining or legal rights is not duress, but using improper threats (like breach of duty, or threats of illegal acts) can be. The Berlik Law blog states that courts look for involuntary acceptance, the absence of alternatives, and the other party’s coercive acts. If those are proven, the contract can be voided by the victim of duress.

Takeaway: Contracts signed at gunpoint (literally or figuratively) won’t hold up. If you were forced to agree by wrongful threats or pressure and had no real choice, you may void the contract for duress. Conversely, when entering agreements, ensure the other side isn’t agreeing under undue pressure – it could later unravel the deal.

Chapter 6: Undue Influence

Explanation: Undue influence occurs when one party unfairly persuades another to enter a contract by abusing a relationship of trust, authority, or vulnerability. Unlike duress (which involves overt threats), undue influence is more subtle – it’s about psychological domination or excessive pressure in a confidential or dependent relationship. The classic scenario is when someone in a position of trust (a caregiver, a family member, a trusted advisor) uses that influence to get an individual to agree to a contract that isn’t in the influenced person’s best interest. Virginia courts have described undue influence as “a species of fraud” because it undermines the free will of the weaker party. The victim isn’t making a truly free decision; instead, their decision has been shaped by the other’s overpowering influence. Contracts (or gifts) produced by undue influence are voidable – meaning the influenced party (or their estate) can ask a court to rescind the agreement.

Real-World Example: An elderly store owner in Alexandria relies heavily on her nephew to manage her finances. The nephew suggests that the aunt sign a contract to sell the store to him at well below market value. He assures her it’s for the best, and due to her trust and dependence on him, she agrees, not fully understanding she’s giving up her business for a pittance. Here, there’s no threat or violence, but the relationship (nephew as trusted caretaker of her affairs) raises a red flag. If the aunt later realizes the unfairness, she could assert that the sale contract resulted from undue influence. The nephew exerted excessive persuasion, taking advantage of her trust and mental frailty, effectively substituting his will for hers. If proven in court (often by clear and convincing evidence), the contract could be voided as fundamentally unfair and not truly the aunt’s free and competent decision.

Virginia Law: Virginia courts require strong evidence of undue influence, particularly in wills and other gifts. However, the principle applies to contracts too. The law states that the influence must be “sufficient to destroy free agency… it must amount to coercion, practically duress”. In other words, the pressure exerted, combined with the vulnerable state of the influenced party, replaced that person’s free will with the will of the influencer. Certain relationships trigger closer scrutiny – for example, if a contract benefits a person who stood in a fiduciary or confidential relationship (like attorney-client, caregiver-dependent, or even close family in some cases), courts may presume undue influence if there are suspicious circumstances (like gross unfairness). One Virginia statute even allows attorney’s fees to a plaintiff who successfully rescinds a contract due to undue influence, underscoring how seriously it’s viewed. The bottom line in Virginia: if someone in a position of trust unfairly advantages themselves in a contract with the person relying on them, the courts are prepared to intervene.

Takeaway: Beware the contract signed under a cloud of influence. If a trusted person manipulated you into an agreement that you wouldn’t have made freely (especially if it’s one-sided in their favor), it may be voidable for undue influence. On the flip side, if you’re in a position of trust making a deal with a dependent person, ensure it’s fair and that they get independent advice – otherwise the contract could be overturned.

Chapter 7: Fraudulent Inducement

Explanation: Fraudulent inducement means one party was tricked into entering a contract by the other’s intentional lies or deception. Essentially, a deal was made, but only because one side relied on false information that the other side knowingly provided. In Virginia, to prove fraud (in a civil contract context), the deceived party must show: (1) a false representation of a material fact, (2) made intentionally or recklessly (knowing it’s false or not caring about the truth), (3) with an intent to mislead, (4) reliance by the victim that is reasonable, and (5) resulting damage. If these elements are met, the contract is voidable for fraud – the defrauded party can rescind (cancel) the contract and/or sue for damages. Fraud in the inducement differs from “fraud in the execution” (covered in Chapter 18) because, here, the person knows they are signing a contract but was lied to about a key aspect of what they are getting or giving. Virginia law does not take fraud lightly; it requires clear and convincing evidence, but if proven, it can impose remedies such as rescission, compensatory damages, and punitive damages.

Real-World Example: A small business is negotiating to buy a delivery truck based on the seller’s claim that “the engine is brand new and in perfect condition.” In reality, the seller knows the engine is 10 years old and has serious issues. The buyer, relying on this false statement, signs the purchase contract at a premium price. This is fraud in the inducement. The condition of the engine is a material fact – it’s central to the buyer’s decision and the truck’s value. The seller’s statement was knowingly false (they were aware of the true engine condition) and clearly made to induce the sale. The buyer reasonably relied on the seller’s representation (perhaps the buyer even asked specifically about the engine, and the seller lied). If the engine fails after purchase and the defect is discovered, the buyer can sue for fraud. They could ask a court to rescind the sale (return the truck and get their money back) or seek damages for the cost of repairs, loss of business, etc., caused by the fraudulent misrepresentation.

Virginia Case Law: Virginia courts have consistently held that fraud vitiates consent – a contract obtained by fraud is voidable at the option of the defrauded party. The Supreme Court of Virginia in cases like Evaluation Research Corp. v. Alequin, 247 Va. 143, 148 (1994), has spelled out the elements of fraud (as listed above) and stressed that the misrepresentation must be about a present or past material fact, not merely a promise of future action (unless, critically, the promisor had a present intent not to perform). In Abi-Najm v. Concord Condo., LLC, 280 Va. 350 (2010), the Court allowed a fraud claim by condo purchasers who were misled by the developer’s statements, reinforcing that a person can pursue fraud even when a contract exists, as long as the fraudulent statements are about present facts and not just contract promises. It’s also noteworthy that Virginia’s “source of duty” rule prevents turning every breach of contract into a fraud claim – the fraud has to arise from an independent, intentional falsehood, not just a broken promise. When true fraud is proven, Virginia courts may award punitive damages (capped at $350,000 by law) and even allow attorney’s fees in some cases of rescission.

Takeaway: Lies that induce a contract can unwind the contract. If someone intentionally misrepresented a critical fact and you signed the deal because of that lie, you have legal recourse – you can potentially void the contract and seek damages for fraud. Honesty in negotiations isn’t just ethical; it’s essential to form a binding contract that will hold up in court.

Chapter 8: Misrepresentation (Innocent or Negligent)

Explanation: Not every false statement is intentional fraud. Sometimes a contract is induced by a misrepresentation that the speaker believed to be true at the time, or perhaps they were careless in stating a fact that turned out false. These are often called innocent misrepresentation (falsehood without knowledge of its falsity) or negligent misrepresentation (falsehood due to lack of reasonable care). While the remedies may differ from intentional fraud, a material misrepresentation – even if made innocently – can be grounds to rescind (cancel) a contract in equity. In Virginia, there is no broad tort of negligent misrepresentation in most contract settings, but equity will allow rescission of a contract for an innocent or negligent misrepresentation of a material fact on which the other party relied. The key difference from fraud is intent: here, the person making the statement isn’t deliberately lying; rather, the statement is objectively false and materially important to the deal. The law deems it unfair to bind someone to a contract based on a significant misrepresentation, even if the misrepresentation was not deliberate.

Real-World Example: A homeowner agrees to sell a house, telling the buyer the roof is only 5 years old, believing it is true because a contractor once said so. In reality, the roof is 15 years old and near the end of its life. The homeowner wasn’t trying to deceive – they were mistaken. The buyer relies on this and enters the contract. This is an innocent misrepresentation of a material fact (roof age and condition are material to a home purchase). If the buyer discovers the truth before closing or shortly after, they could seek to rescind the purchase contract. Even though the seller didn’t lie on purpose, the buyer made the agreement under a false impression about a key element of the deal. Many courts (including Virginia’s equity courts) would allow rescission in such a case, restoring both parties to their pre-contract position. The buyer would get out of the contract (or get their money back if closed), and the seller would get the house back, because enforcing the contract would be unjust given the materially false premise.

Virginia Perspective: Virginia law has historically permitted rescission for material misrepresentation, even when made in good faith. An old Virginia case note (and subsequent cases following that principle) explains that a seller cannot avoid rescission by saying the misrepresentation was innocent – if it was material and induced the buyer to contract, equity may grant rescission. In practical terms, Virginia differentiates between actual fraud (with intent, which can give rise to damages and tort claims) and constructive or innocent misrepresentation (which typically gives rise to the equitable remedy of rescission, not damages for fraud). For instance, if you bought a business based on the seller’s wrong statement of last year’s profits (and the seller reasonably thought it was true, perhaps due to an accounting error), Virginia courts could allow you to cancel the contract because the basis of the bargain was materially misstated. However, you might not get damages unless you prove the seller was at least negligent or had a duty to know the truth. The Law Offices of SRIS explains that for innocent or negligent misrepresentation, rescission is often the main remedy – the goal is to put parties back where they started. You usually cannot get punitive damages without intentional fraud, but you don’t have to be stuck in a contract built on a significant mistake of fact.

Takeaway: A materially false statement, even if made in good faith, can render a contract void. Always double-check the important facts before you sign. If you entered an agreement based on a critical factual mistake (whether yours or the other side’s), you may be able to cancel the deal. Honesty and accuracy protect everyone – if you’re the one making representations, be sure of your facts to avoid later headaches.

Chapter 9: Mutual Mistake

Explanation: A mutual mistake occurs when both parties to a contract are mistaken about a fundamental fact that is central to the agreement. This is not just a minor misunderstanding – it’s a substantial error about something important, existing at the time of the contract, which goes to the very heart of the deal. When both parties share the same mistaken belief, the law may allow the contract to be rescinded because there was no true meeting of the minds regarding that essential fact. The rationale is that if both sides were wrong about a basic assumption, then what they thought they agreed upon doesn’t actually exist. Classic examples include both parties being mistaken about the identity or existence of the subject matter of the contract (e.g., unknowingly contracting for a painting that had already been destroyed). In Virginia, a mutual material mistake can justify rescission of the contract, so neither party is unfairly bound by an agreement based on a false premise.

Real-World Example: A buyer and seller contract for the sale of a specific antique violin for $10,000, believing it to be a rare Stradivarius. Both are acting under the assumption (and perhaps an old appraisal) that it’s authentic. After the sale, an expert reveals it’s just a replica worth $500. Here, both buyer and seller shared the same mistaken belief about a basic fact – the identity/value of the violin. This is a mutual mistake regarding a material aspect (the item’s authenticity). Enforcing the contract would saddle the buyer with a $500 violin for $10,000 and give the seller an unwarranted windfall. In equity, a Virginia court would likely permit rescission of the sale. The contract can be unwound because neither party got what they bargained for – the buyer didn’t get a real Stradivarius, and the seller (assuming they were genuinely mistaken too) didn’t intend to sell a mere replica. By canceling the contract, the court returns both parties to their pre-contract positions, which is the fair result when a mutual mistake undercuts the deal.

Virginia Case Law: Miller v. Reynolds, 216 Va. 852 (1976), is a classic Virginia case on mutual mistake. In that case, a parcel of land was sold under the mutual belief it could support a septic system for building a home. Both seller and buyers were mistaken – the land couldn’t actually be built on due to soil issues. The Virginia Supreme Court held that this was a mutual, material mistake going to the essence of the contract (the land’s suitability for a home) and ordered rescission. The Court stated that “the mistake was a mutual mistake, and a material one, affecting the substance of the contract. The equities of this case clearly require rescission.”. In short, both parties were mistaken about the nature of the sale (a buildable lot), so the contract was rescinded to avoid injustice. Virginia follows the general rule: if a mutual mistake concerns a basic assumption that materially affects the agreed performance, the contract may be voided at the request of the adversely affected party, as long as they didn’t bear the risk of that mistake (for example, via a contract clause assuming the risk). Equity aims to be fair: you shouldn’t be locked into a deal that neither of you truly understood.

Takeaway: When both parties are mistaken about a material fact, the contract can be voided. If you discover that both you and the other side shared a fundamental mistake about what you agreed on, consult an attorney – you may be able to rescind the contract. It’s a reminder to double-check critical facts (like condition, authenticity, zoning, etc.) before finalizing a deal.

Chapter 10: Unilateral Mistake

Explanation: A unilateral mistake is when one party to the contract is mistaken about a basic fact, and the other party is not mistaken. Generally, a unilateral mistake is not, by itself, grounds to void a contract – the law expects people to be careful in their agreements. However, there are important exceptions. If the non-mistaken party knew or had reason to know of the other’s mistake, and the mistake is about a material term, a court may grant relief (like rescission) to the mistaken party. It would be unfair for one party to snap up a deal knowing the other made a typo or a calculation error. Another scenario is if the mistake was a clear clerical error (such as a decimal point error in a bid) and enforcing the contract would be unconscionable, the court might allow it to be corrected or rescinded, especially if promptly noticed and causing no prejudice to the other side. The key factors are: the mistake is material; the mistake did not result from gross negligence; and the other party either knew about it or it would be unduly harsh to hold the mistaken party liable.

Real-World Example: A contractor submits a bid to build an office for $100,000, accidentally omitting a “1” and intending it to be $110,000. The client immediately recognizes this is significantly lower than other bids (around $110k) and promptly accepts the contract. Here, the contractor made a unilateral pricing error. If the client had reason to suspect a mistake (the price disparity) and tried to take advantage of it, a court could find it inequitable to enforce the $100,000 price. Especially if the contractor catches the error quickly and the project hasn’t substantially begun, a Virginia court might allow rescission or reformation of the contract due to the other party’s unilateral mistake, known (or obviously should have been known) to that party. On the other hand, if the mistake was more subtle and the client had no reason to know (and they relied on that price), courts are less forgiving – the contractor might be stuck with the bad deal. Each case is fact-specific.

Virginia Perspective: Virginia law, echoing general contract principles, holds that a unilateral mistake alone is usually not enough to void a contract. However, one party’s mistake can be remedied if the other party knew or should have known of the mistake at the time of contract formation. The Virginia Supreme Court in Phillips v. Mazyck noted that if one party knows or has reason to know that the other party is mistaken about the agreement, then there’s no true meeting of the minds. This effectively prevents someone from snapping up an offer they recognize as an obvious error (like a house listed for $50,000 that was supposed to be $500,000 – clearly too good to be true). Additionally, where a unilateral mistake is coupled with some inequitable conduct by the other side or is so severe that enforcing the contract would “shock the conscience,” Virginia courts may intervene. For instance, in bidding contexts (especially construction contracts), if a contractor promptly proves a clerical mistake in a bid and the owner hasn’t relied to their detriment, courts have occasionally allowed the contractor to withdraw the bid without penalty, recognizing the unilateral mistake in the interest of fairness. The bottom line is this: unilaterally terminating a contract is difficult, but possible if the above conditions are met.

Takeaway: Your mistake, generally your loss – unless the other side knew or exploited it. Always double-check your contract terms and calculations. If you realize you made a big mistake in an agreement, act immediately. You may have a shot at relief if the error is fundamental and the other party hasn’t been misled to their harm – especially if they suspected or should’ve suspected the mistake. But unilateral mistakes are uphill in contract law, so diligence up front is your best bet.

Chapter 11: Unconscionability (Contracts of Adhesion)

Explanation: Unconscionability is a doctrine that allows courts to refuse to enforce contracts (or specific terms) that are extremely one-sided and fundamentally unfair at the time of signing. It’s often described as an absence of meaningful choice for one party, combined with terms that unduly favor the other. There are two aspects: procedural unconscionability (the process was unfair – e.g., fine print, no negotiation, disparity in bargaining power, or deceptive tactics) and substantive unconscionability (the terms themselves are outrageously unfair or oppressive). In Virginia, a classic setting for unconscionability is the contract of adhesion – a pre-printed, take-it-or-leave-it contract prepared by a stronger party and presented to the weaker party with no real opportunity to negotiate (think consumer contracts with giant corporations). Not all adhesion contracts are unconscionable, but if a term “shocks the conscience” – so extreme that no person in their right mind would agree and no fair person would impose it – a Virginia court can strike it or void the contract. Unconscionability is a high bar – it’s reserved for egregious cases, not just a bad deal or a tough bargain.

Real-World Example: A struggling small business needs a short-term loan. A lender offers a one-page contract at a very high interest rate. Desperate, the owner signs without a lawyer. Hidden in the fine print is a clause stating that if a single payment is late, the interest rate jumps to 200% annually and the lender can take immediate ownership of the business’s assets. This term is exploitative. The business owner had limited bargaining power (urgently in need of funds) and likely didn’t understand the draconian penalty clause. The 200% interest and immediate asset seizure is the kind of term a court might find substantively unconscionable – “no man in his senses and not under delusion would make, and no fair man would accept” such a deal. If the lender tried to enforce that clause, a Virginia court could refuse, noting how shocking and one-sided it is. The court might void that clause or even the whole contract, especially given the take-it-or-leave-it nature and the borrower’s lack of choices.

Virginia Law: Virginia courts, in Smyth Bros.-McCleary-McClellan Co. v. Beresford, famously defined an unconscionable contract as one “that no man in his senses and not under a delusion would make on the one hand, and that no fair man would accept on the other”. The inequality must be so gross as to “shock the conscience”. In practice, Virginia has voided or stricken terms – for example, in consumer transactions or leases – where one side had all the leverage and imposed harsh terms that the signer likely didn’t understand. A recent trend is scrutinizing arbitration clauses or liability waivers buried in contracts that strip away fundamental rights, though Virginia courts will enforce such clauses unless they are truly unconscionable. Another hallmark is extreme pricing in certain contexts (though merely a high price usually isn’t enough unless coupled with trickery or no choice). It’s worth noting that Virginia’s public policy: contracts against public policy or illegal (Chapter 12) are different, but an unconscionable contract often also violates public policy by its oppressiveness. Also, as of 2021, Virginia has specific laws voiding non-compete agreements for low-wage workers – that’s legislative recognition of unconscionability in a specific context (though framed as public policy). In general, unconscionability in Virginia requires a combination of factors: a vastly superior bargaining power, an absence of meaningful choice, and oppressive, lopsided terms at the time of signing. It’s a safety valve to prevent enforcement of “contracts” that look more like exploitation than a meeting of equals.

Takeaway: Courts won’t enforce a deal that is egregiously unfair. If you’re handed a “take-it-or-leave-it” contract with outrageous terms, that contract (or its worst parts) might not hold up. Still, don’t count on courts saving you from a bad bargain – unconscionability is for extreme cases. Always read contracts (even the fine print) and negotiate what you can. If a term seems crazy-unfair, it probably is – and you should think twice before signing, or seek legal advice.

Chapter 12: Illegality and Public Policy

Explanation: A contract that involves doing something illegal or that violates public policy is void from the start – it’s as if the contract never existed in the eyes of the law. Courts simply won’t enforce an agreement to do something unlawful or against the well-established public interest. Illegality can be obvious (e.g., a contract to buy illegal drugs, or to hire someone to break the law) or sometimes more subtle (e.g., a contract that violates a licensing requirement or a usury law). Public policy violations include agreements that aren’t crimes but would harm the public interest, such as overly broad non-compete agreements (in some cases), contracts that obstruct justice, or contracts that involve immoral acts. In Virginia, any contract made in violation of a statute is void – no one can sue on it. For example, Virginia has a statute capping interest rates; a loan contract charging above the legal interest limit (usury) is void and unenforceable. Similarly, if a business is required to have a license (say a contractor’s license) and doesn’t, contracts it enters for that unlicensed work might be unenforceable. The idea is the law won’t recognize private agreements that flout the law or certain societal principles.

Real-World Example: A catering company in Alexandria secretly agrees to pay a rival $10,000 to not bid on a lucrative city contract (a classic bid-rigging arrangement). They even put it in writing, calling it a “consulting agreement.” This contract is illegal and against public policy (it constitutes commercial bribery and undermines the competitive bidding process). If the rival took the $10,000 and the catering company then sued to enforce any aspect of that “agreement” (for example, if the rival still bid on the project in breach of its promise), the case would be dismissed. A court will not enforce a contract that is anti-competitive or unlawful. Likewise, if two parties contract to do something that requires a government permit and they don’t obtain it, or to do something that violates zoning or safety laws, those contracts are void. Another example: a contract to waive one’s right to workers’ compensation in advance (against public policy in many states), or an employment contract to work in violation of labor laws. These won’t be upheld.

Virginia Law: Virginia is clear that contracts for an illegal purpose are void ab initio (from the outset). Illegal = void, period. For instance, Virginia Code § 6.2-303 sets maximum interest rates; any contract charging above that rate is void for the excess interest (and possibly void in full). The Berlik Law blog puts it succinctly: “A void contract is considered a nullity and has no legal effect. A contract made in violation of a Virginia statute, for example, would be illegal and therefore void”. They give the specific example that a contract calling for usurious interest is void. Another area is public policy: Virginia has, through case law, voided certain contracts that, say, unreasonably restrain trade (overly broad non-compete agreements can be struck down, though that’s usually analyzed under specific non-compete doctrine rather than general illegality – but it’s a cousin of public policy reasoning). Virginia also won’t enforce contracts that interfere with the administration of justice (like paying a witness to disappear). Additionally, any contract to commit a crime or a tort is obviously void. It’s worth noting that if a contract can be performed in a lawful way but one party intends an illegal use, that doesn’t necessarily void the contract unless the other party knew (for example, selling a knife isn’t void even if the buyer intends something bad, but selling something specifically for an illegal purpose is different). Ultimately, a party cannot go to court to seek help with an agreement that the law condemns – the court will leave the parties where it finds them (often quoting, “No court will lend its aid to a man who founds his cause of action upon an immoral or illegal act.”).

Takeaway: If the contract’s object or effect is illegal, it’s DOA – dead on arrival. You can’t enforce a contract to do something unlawful or seriously against the public interest. For small businesses, ensure your agreements comply with laws (licensing, regulations, etc.). For individuals, remember that a shady deal (no matter how good on paper) isn’t a deal at all in court. When in doubt, ask “Does this agreement violate any law or public policy?” – if yes, walk away (and possibly notify the authorities if appropriate).

Chapter 13: Statute of Frauds (Writing Requirement)

Explanation: The Statute of Frauds is a legal doctrine that requires certain types of contracts to be in writing and signed to be enforceable. The purpose is to prevent fraud and misunderstandings in significant transactions by ensuring there’s written evidence of the agreement. In Virginia (as in other states), the Statute of Frauds typically covers contracts such as: (1) contracts for the sale of land or real estate, (2) contracts that cannot be performed within one year, (3) promises to pay someone else’s debt (surety agreements), (4) agreements made upon consideration of marriage (like prenuptial agreements), (5) contracts for the sale of goods priced at $500 or more (under the UCC, with exceptions), and a few others specified by statute (for example, a promise by an executor to pay estate debts out of their own pocket). If a contract falls under the Statute of Frauds and isn’t in writing, it’s not necessarily void, but it is unenforceable – meaning if one party refuses to perform, the other can’t win in court (the defense is “Statute of Frauds – no written agreement”). The writing doesn’t have to be a formal contract; a signed memo, email, or a combination of writings can suffice, as long as it reasonably identifies the parties, subject matter, and essential terms.

Real-World Example: You verbally agree with a friend to purchase their house in Alexandria for $300,000. You shake hands and maybe even exchange a few texts, but never sign a formal contract or deed. Later, your friend gets a higher offer and refuses to honor your deal. Because this is a contract for the sale of real estate, the Statute of Frauds applies – Virginia law (and virtually every jurisdiction) requires a writing signed by the party to be charged (in this case, the seller) for a real estate contract. Your handshake and casual texts likely won’t meet the standard (especially if essential terms like the closing date aren’t clear, or the friend didn’t sign an agreement to sell). Thus, you cannot enforce the purchase – the friend can successfully assert the Statute of Frauds as a defense. Another example: You hire someone for two years of work on a handshake – if they walk away after a year, the second year isn’t enforceable absent a writing, because the contract couldn’t be performed within one year of its making. The Statute of Frauds would preclude an oral claim for a 2-year employment contract.

Virginia Law: Virginia’s Statute of Frauds is codified in Va. Code § 11-2 and other sections. For instance, Va. Code § 11-2 explicitly requires a signed writing for contracts for the sale of real estate and leases longer than a year. It also covers agreements not to be performed within a year, promises to answer for another’s debt, and so forth (these mirror the old English Statute of Frauds categories). If these agreements aren’t written, they’re unenforceable in court. The Virginia Business Litigation Blog notes, for example, that a neighbor’s alleged oral promise to sell his house for $500,000 would fall through if not written – you “can probably get out of the deal” if nothing was put in writing. It’s not that the contract doesn’t exist at all – it’s just that the courts won’t enforce it without the required writing. There are exceptions: courts sometimes enforce oral contracts in Statute of Frauds territory if there’s part performance (especially in real estate, where the buyer took possession and made improvements in reliance on the oral contract, and equity might enforce it to avoid fraud) or on other equitable grounds. But those are difficult and fact-specific avenues. The safest path is: if your contract needs to be in writing, get it in writing signed by the other party. In today’s world, that could include electronic writings under the E-Sign Act (an email with an e-signature can count). But don’t rely on handshake deals for anything the law requires to be written.

Takeaway: Some deals must be written, or you’re out of luck. Know when the law demands a writing – especially for real estate, long-term agreements, large goods sales, etc. For those, a verbal “deal” isn’t a done deal until paper (or electrons) are signed. When in doubt, put it in writing anyway; it’s just good practice to avoid memory lapses and disputes.

Chapter 14: Lack of Capacity – Minors

Explanation: Capacity refers to a person’s legal ability to enter a contract. Minors (in Virginia, those under 18) generally lack the capacity to be bound by a contract. The rule exists to protect young people from exploitation stemming from immaturity or limited experience. A contract made by a minor is typically voidable at the minor’s option. This means the minor can cancel the contract (disaffirm it) before or within a reasonable time after reaching 18, and they’ll usually need to return any goods received. The adult party, however, is bound – only the minor can void it, not the other way around. There are a few exceptions: contracts for “necessaries” (essential items such as food, shelter, clothing, and medical services) may be enforced against a minor to ensure that providers of necessaries are paid (though often only at a reasonable value, not an inflated price). Also, certain student loans or military enlistment contracts involving minors have special rules. But the general principle remains: minors are not stuck with their contracts if they don’t want to be, which is why businesses should be cautious when contracting with someone under 18.

Real-World Example: A 17-year-old high school student in Alexandria signs a year-long gym membership contract, agreeing to pay $50 per month. After two months, he decides he no longer wants it (perhaps he realized he needs the money for school supplies). He notifies the gym that he’s canceling. In this scenario, as a minor, the student has the right to disaffirm the contract. The gym cannot enforce the remaining payments because the contract is voidable by the minor. Typically, the minor should return any benefits if possible – in a gym context, he can’t “return” used gym time, but he could be liable for the two months he used (since those services were consumed). However, he won’t owe for the remaining term after disaffirmance. If the same contract were made after he turned 18, it would be fully binding. Also, if he kept using the gym past his 18th birthday without canceling, he might be seen as ratifying the contract (accepting it) as an adult and then would be on the hook.

Virginia Law: Virginia follows the common law rule on minors: contracts made by minors are voidable at the minor’s election (with the exception of necessaries and some statutory tweaks). As noted in a legal summary, contracts involving minors (under 18) are categorized as voidable – the minor can reject them, or they can ratify them upon reaching majority. If a minor misrepresents their age and the other party is duped, that can complicate matters, but generally, Virginia still allows disaffirmance (though some states are harsher on minors who lie about age). When a minor turns 18, if they want a previously signed contract to continue, they should explicitly ratify it or continue to accept benefits and perform obligations after 18; then it becomes binding. One should also note that Virginia allows minors who are emancipated (via court order or marriage, etc.) to have capacity as if an adult for contracts. But absent emancipation, the protective rule remains in effect. A minor who voids a contract usually must return whatever they obtained (if still in possession) to prevent unjust enrichment, and they can generally recover what they’ve paid or given, too. The bottom line is that businesses dealing with minors should ideally obtain a co-signature from a parent or guardian (who is fully liable), because the minor alone can walk away from many deals.

Takeaway: Those under 18 have an escape hatch from contracts. If you (or your teen) signed a contract while underage, you can often cancel it – but you must act in a timely manner (upon or shortly after turning 18) and return what you can. If you’re contracting with a minor, know that they can void the deal – so consider requiring a parent’s guarantee or waiting until they’re of age for significant agreements.

Chapter 15: Lack of Capacity – Mental Incompetence

Explanation: Contracts require that each party have the mental ability to understand what they’re doing. If someone is mentally incapacitated at the time of contracting – for example, due to a mental illness, cognitive impairment, or severe intellectual disability – the contract may be voidable or even void. The test is whether the person can comprehend the nature and consequences of the transaction and make a rational decision about it. If a court has formally adjudicated someone as incompetent and appointed a guardian/conservator, that person generally cannot make a binding contract (any contract is void). If no such adjudication exists, a contract made by a person who lacked mental capacity at the time (e.g., they were in a state of dementia or suffering from a condition that impaired judgment) is usually voidable by that person or their estate. They (or their guardian) would need to show they didn’t understand what they agreed to. Often, fairness requires restoring whatever was exchanged – similar to minors, they may have to return any benefits if possible. The idea is protecting those who cannot protect themselves, while being fair to the other side who may not have known of the incapacity.

Real-World Example: An elderly man with advanced Alzheimer’s disease is persuaded to sign a contract selling his house to a neighbor for far below market value. The man, in a confused state, doesn’t really grasp that he’s giving up his home. Here, the elderly man lacked the mental capacity to contract – he couldn’t understand the nature and effect of the sale. That contract is voidable (and likely void if a court would find his mental capacity was essentially nonexistent). His family or legal representative could go to court, present medical evidence of his condition, and seek to rescind the sale contract. The neighbor would have to return the house title, and any money paid by the neighbor would be returned. Virginia law requires a person have enough reason to understand the transaction; clearly, in this scenario, the standard wasn’t met. Another example might be a person in a manic episode of bipolar disorder who signs an impulsive, onerous contract – that might be voidable if they can show they weren’t in a lucid state to consent.

Virginia Law: Virginia case law (e.g., Bailey v. Bailey, 54 Va. App. 209 (2009)) states that to have capacity, a person must be able to understand the nature and consequences of the transaction and to act rationally in relation to it. The existence of a mental impairment alone isn’t enough; it must be shown that, because of that impairment, the person could not comprehend what they were doing at the time of contracting. If that’s proven, the contract can be voided. Virginia also recognizes the concept of lucid intervals: a person with a mental illness may have periods of clarity during which they understand; a contract signed in a lucid interval can be valid even if the person was incompetent at other times. Importantly, intoxication (to be discussed next) is a temporary form of incapacity, but chronic substance abuse leading to impairment might fall here too. Contracts made by someone under a guardianship (meaning a court already found them incapacitated) are generally void, period. Otherwise, it’s voidable with proof. Equity will typically require restoration of the status quo: if the incompetent person received something tangible, it should be returned if possible (to avoid unjust enrichment). But if someone knowingly took advantage of a mentally impaired person, courts can also fashion equitable remedies to discourage such exploitation.

Takeaway: Capacity matters – you need a sound mind to make a binding contract. If you or a loved one didn’t understand what was being signed due to mental incapacity, that agreement can likely be undone. This is why it’s crucial to involve caregivers or attorneys when elderly or disabled individuals enter into contracts. And for businesses, dealing fairly and carefully in such situations isn’t just ethical – it protects your contract from being invalidated later.

Chapter 16: Lack of Capacity – Intoxication

Explanation: Can you get out of a contract because you were drunk or high when you agreed? The answer is: possibly, but it’s not easy. Voluntary intoxication is a form of temporary incapacity. The law doesn’t allow people to routinely escape their contracts by claiming they had a few too many – otherwise, chaos would ensue. However, if a person was so extremely intoxicated that they could not understand the nature of the transaction or the obligations it entailed, then they lacked capacity at that moment, and the contract could be voidable by them once they sobered up. The intoxication must be so severe that the person’s mental state is comparable to mental incompetence. If the other party purposely caused or encouraged the intoxication to obtain the contract (say, getting someone drunk to sign a contract), courts are more inclined to void it as a sort of fraud or duress scenario. Generally, the intoxicated person would need to disaffirm the contract promptly upon regaining sobriety and return any consideration they received. If they delay or act as if they accept the contract while sober, they may be deemed to have ratified it.

Real-World Example: After celebrating a big promotion, a man in Arlington has way too much to drink. In his inebriated state, he meets someone who offers to sell an “amazing” investment – a set of rare coins – for $50,000. The man, not comprehending what he’s doing, scribbles his signature on a purchase agreement. The next morning, he realizes what happened. If the evidence shows he was extremely intoxicated and truly did not understand the deal’s nature or that he was obligating himself to pay $50,000, he can likely void that contract. Virginia law (and general contract law) would consider whether he had the capacity to understand the transaction. He’d need to act quickly to disaffirm (and certainly not accept the coins or make payments once sober). On the flip side, if he was merely “buzzed” and just exercised poor judgment, the contract stands. The threshold is high – essentially, he must have been incapable of reasonable judgment at the time. It helps if there’s evidence, say witnesses who saw he was blackout drunk, or receipts of an enormous bar tab, etc. If the seller knew he was in a position of weakness and took advantage, a court won’t enforce that unfair deal.

Virginia Perspective: Virginia recognizes that intoxication can deprive a person of capacity. The Berlik Law blog explicitly gives the example: “if you were drunk when you agreed to enter into a contract, you may be able to get out of it by showing that you lacked the capacity to incur contractual duties at the time you signed”. This suggests that Virginia courts would void a contract if the party was so intoxicated that they didn’t understand what they were doing. However, Virginia courts are cautious – being “drunk” is not a get-out-of-contract-free card unless it truly reaches the level of incapacitation. The burden is on the intoxicated person to prove their incapacity. Typically, they must show they were so far gone that they could not comprehend the contract’s nature, and the other party either knew or should have known of their condition. Also, Virginia, like other states, expects a person who wakes up from that state to promptly repudiate the contract if they intend to – any significant delay or benefit-taking might be seen as affirming it while sober. This area overlaps with equity: courts don’t favor exploitative contracts (as in the coin-seller example).

Takeaway: “In vino veritas” doesn’t apply to contracts – a blackout drunk promise isn’t binding. But claiming intoxication is a narrow defense: it only works if you were so impaired you essentially had no idea what you were doing. The safe bet is not to sign important documents under the influence. If you did and regret it, act immediately to void the deal and offer to return the item. Don’t expect sympathy if it was just a case of “liquid courage” and next-day buyer’s remorse; the law only protects those who were truly incapable at the time of agreement.

Chapter 17: Lack of Authority (Agency Issues)

Explanation: Sometimes, disputes arise not over the terms of a contract, but over who is bound by it. In business, one person (an agent) may sign a contract on behalf of another (the principal, such as a company). The issue of authority is crucial: if the signer lacked authority to bind the principal, the contract might not be enforceable against the principal. Conversely, the signer might be personally liable if they lacked authority and the other party relied on the signature. There are different types of authority: actual authority (express or implied permission given by the principal to the agent), and apparent authority (the principal’s actions lead a third party to reasonably believe the agent has authority). If someone signs a contract without any authority, and no reasonable appearance of authority, then there’s no valid agreement with the purported principal – essentially, the “contract” might bind nobody (or just the unauthorized signer individually). This comes up often in small businesses – e.g., an employee or a business partner signs a big contract without permission. If your company’s name is on an agreement but the signer wasn’t authorized, you may argue the contract is not valid against the company.

Real-World Example: Jane is a junior employee at a Virginia LLC. Without the owner’s knowledge, she signs a contract with a supplier for a costly, long-term commitment on behalf of the company. Jane did not have the authority in her role to do that (say, her job is marketing, not procurement). When the owner learns of it, he’s shocked and states the company isn’t bound by that unauthorized contract. Here, if Jane truly lacked actual authority (the boss never gave such power), the question is whether the supplier reasonably thought she had authority – perhaps the supplier dealt with her before or she has a title that normally might involve contracts. If not, the contract might be void as to the company. The supplier could only enforce it against Jane personally (if at all). This is a lack-of-authority scenario. On the flip side, if Jane were the sales manager and normally entered into contracts, the supplier might argue that she had apparent authority (from her title or prior dealings) and thus the company should be bound. Courts would assess what a reasonable third party would believe about Jane’s authority. If it’s clear no reasonable person would think a “secretarial intern” (for example) could sign a major contract, then the company isn’t bound. So authority can make or break a contract’s enforceability.

Virginia Perspective: Virginia follows standard agency law principles. If an agent acts with actual or apparent authority, the principal is bound by the contract. If not, the principal is not bound. A leading Virginia case on apparent authority (often in the context of real estate or business contracts) would look at whether the principal cloaked the agent with some indicia of authority that misled the third party. The Binnall Law Group (Alexandria commercial litigation) explains that explicit authority may be proven by corporate bylaws or a board resolution, implied by job duties, and apparent authority by the principal’s manifestations to third parties. They give an example: a sales manager explicitly allowed to sign client contracts binds the firm, but an intern obviously does not. Virginia courts often hold that a person dealing with an agent is expected to verify the agent’s authority when the circumstances would prompt a prudent person to do so. For instance, in Wright v. Shortridge, 194 Va. 346 (1952), an interesting older case, the court refused to bind a homeowner to a contract signed by a neighbor purportedly on her behalf – the “agent” clearly had no authority. The rule: no authority, no contract (with the purported principal). However, if the principal later ratifies the unauthorized act (accepts the benefits or otherwise affirms it), then it’s as good as if authority existed from the start. Small business owners should be careful: if an unauthorized employee makes a deal you don’t want, object immediately and don’t accept any benefits from it. For the outsider contracting, it’s wise to get confirmation of the signer’s authority (like a corporate resolution or officer title). In sum, in Virginia as everywhere, the validity of contracts often hinges on whether the signer had the power to bind the entity they claimed to represent.

Takeaway: Ensure the signer has the authority to sign. If you’re a business, clearly delegate authority to sign deals (and tell your partners). If you’re contracting with a company, consider asking, “Are you authorized to sign this?” and note their title or get written confirmation. Lack of authority can torpedo a contract – or leave you chasing someone who might not have the resources (like an employee). In short, a contract signed by an unauthorized person is like a check signed by someone not on the account – it bounces.

Chapter 18: Fraud in the Execution (Fraud in the Factum)

Explanation: Fraud in the execution (also known as fraud in the factum) occurs when a person is deceived about the nature of the document they are signing. In these cases, the signer doesn’t realize they’re entering a contract (or they think it’s a different contract than it actually is), due to the other party’s trickery. This is different from fraud in the inducement (Chapter 7), where the person knows they’re signing a contract but was misled about material facts. Fraud in the execution is more extreme: the person’s intent to contract is itself obtained through deception. Contracts obtained by fraud in the execution are usually considered void, not just voidable, because there was never any true consent to contract at all. Common scenarios: swapping out documents for signature, misrepresenting what a document is (“This is just a receipt” when it’s actually a contract), or forging someone’s signature. Since the person didn’t knowingly agree to the contract, it’s as if it never happened. However, proving fraud in the execution can be tricky, and third parties relying on the contract (who had no clue about the fraud) can complicate matters (like a bank that bought a promissory note that someone was tricked into signing – there are special rules there).

Real-World Example: A non-English-speaking individual is given a document to sign, which the other party describes as “an application form” for a service. In truth, it’s a guarantee agreement, making them liable for someone else’s debt. The individual signs, not understanding the document’s true nature. This is fraud in the execution. The signer did not intend to sign a guarantee; they thought they were signing something else entirely. Because they were misled about what they were signing, there was no actual consent to that guarantee contract. Under these circumstances, a court would treat the guarantee as void due to fraud in the factum – essentially, the “agreement” is null and void. Another example: someone shuffles papers and gets an elderly person to sign a “birthday card,” but one of the papers is actually a deed transferring their house. That deed is void for fraud in execution. The key element is that the victim never realized a contract (or that particular obligation) was being made.

Virginia Perspective: Virginia rarely uses the term “fraud in the factum” in everyday court opinions, but the concept exists. A contract requires a knowing assent – if someone is tricked into signing something without knowing it’s a contract, there’s no assent. A notable historical reference: Van Deusen v. Snead, 247 Va. 324 (1994), touches on duty to disclose in contexts that can verge on fraud in execution (though it’s more about misrepresentation). Generally, Virginia aligns with the rule found in many sources: fraud in the execution invalidates contractual obligations, rendering them unenforceable. The UpCounsel article we consulted confirms that if fraud in the factum is proven, the contract is considered void. Virginia’s Uniform Commercial Code (for negotiable instruments) explicitly recognizes fraud in the factum as a real defense that can void an instrument even against a holder in due course (UCC § 3-305). For ordinary contracts, the principle is the same: there was no true meeting of minds. The difficulty is evidentiary – the one alleging “I didn’t know what I was signing” must persuade the court that it wasn’t just a failure to read, but active deception preventing understanding. Virginia courts would distinguish between someone who did not read a contract (generally not an excuse) and someone who was deceived about what the document was (an excuse if proven). If accused of signing something, usually the law expects you to have read it; but if you were tricked about the very character of the document, that’s a different matter.

Takeaway: If you didn’t even know it was a contract, you didn’t consent. A signature obtained by sleight-of-hand or lies about the document’s nature is not binding. This is rare, but it does happen (especially to vulnerable people). Always be sure you know what you’re signing – ask, translate, read. If you realize you were misled into signing something you never intended to, seek legal counsel immediately. Such a document can be declared void. Remember: signing blindly is dangerous, but tricking someone into signing is downright fraud that strikes at the heart of contract law.

Chapter 19: Preliminary Negotiations vs. Binding Contract

Explanation: Not every agreement during negotiations is a binding contract. Often parties discuss and even agree on terms “in principle,” but intend to finalize them in a formal, written contract later. The question arises: when are parties actually bound, and when are their communications just part of ongoing negotiations or an “agreement to agree” in the future? A true contract requires intention to be bound now on agreed terms. If key terms remain open, or the parties explicitly state “subject to contract” or “we’ll sign a formal agreement,” there is generally no binding contract until that formal step is taken. However, if the parties reach an agreement on all material terms and demonstrate intent to be bound (even if a more detailed document is contemplated later), a contract can exist through email, term sheets, or handshakes. The waters can be muddy, which is why clear wording is important. An “agreement to agree” (like “we’ll negotiate a lease in the future”) is usually not enforceable because it’s too indefinite and shows the parties knew they hadn’t finished negotiating. In Virginia, as elsewhere, courts look at whether the parties intended to conclude a contract or merely to continue talks. Additionally, letters of intent or memoranda of understanding often state whether they are binding. Some parts may be binding (like confidentiality clauses) while the rest is not.

Real-World Example: Two businesses exchange a series of emails about a potential joint venture. They outline the basic terms: each will invest $50k, and they’ll split profits 50/50. The last email says, “Looks like we are in agreement. I’ll have our lawyers draft a formal contract for both of us to sign next month.” Before that formal contract is signed, one party backs out. Is there a binding contract from the emails? Probably not, because the explicit reference to drafting a formal contract indicates an intent not to be bound until that happens. The phrase “we are in agreement” sounds promising, but “we will sign a formal contract” creates a strong presumption that no contract exists yet. Under Virginia law, when parties clearly intend to execute a definitive contract at a later date, the courts presume no contract exists until the document is signed. Conversely, if those emails contained all essential terms and the parties’ conduct demonstrated they had commenced performance, a court might find a contract even without a formally signed document if it appeared the parties intended the emails to be binding.

Another scenario: A letter of intent (LOI) for the purchase of a business sets out the price and key terms but states, “This LOI is non-binding, intended only to outline terms for a definitive agreement to be executed.” That’s not a contract (except perhaps certain clauses, such as exclusivity, if stated as binding). If negotiations break down, neither party can enforce the LOI as a contract because it was designed to be a preliminary negotiation document.

Virginia Case Law: The Virginia Supreme Court in Moorman v. Blackstock, Inc., 276 Va. 64 (2008) and Phillips v. Mazyck (mentioned earlier) dealt with situations where parties were negotiating and one side claimed a contract existed before the final document. In Moorman, the Court emphasized that if parties contemplate a later formal contract, there’s a presumption that nothing is binding until that happens. “Overcoming such a presumption requires strong evidence” to show they intended to be bound earlier. The Court basically echoed the general rule: where parties intend to culminate their agreement with a signed contract, there is a strong presumption that no contract exists until that contract is signed. In another case, Highways v. 496 Elden St. LLC (Va. App. 2025), email exchanges on a settlement were argued to be a binding deal; the court looked at whether an “Agreement After Certificate” was expected to be signed and concluded that without the signature, no final settlement contract was reached. Essentially, Virginia courts will enforce a binding preliminary agreement if it’s clear that’s what both parties intended, but they won’t force someone to honor what was only meant as a draft or negotiation stage. Terms such as “subject to contract” or “we’ll formalize later” are usually decisive in establishing that no current contract exists. Meanwhile, if parties say “deal” and shake hands on all terms and start acting on it, Virginia would likely find a contract even if paperwork comes later.

Takeaway: Is it a deal or just a draft? Clarity is key. To avoid confusion, explicitly state your intent. If you don’t want to be bound until a formal contract is signed, say exactly that in your communications. If you think you have a binding agreement via emails or handshake, be aware the other side might not – the law will examine whether both intended to be bound. In short, don’t assume. Formalize important agreements in a signed contract, or if you’re in early stages, use phrases like “non-binding” to protect yourself. Preliminary negotiations are like dating – until you both say “I do” in the contract world, either can walk away.

Chapter 20: Void vs. Voidable Contracts and Ratification

Explanation: Throughout these chapters, we’ve mentioned that some contracts are “void” and others “voidable.” It’s important to distinguish between ratification (when a voidable contract is affirmed) and the concept of ratification. A void contract is one that is a nullity – it has no legal effect from the start. Neither party can enforce it. Examples: contracts for illegal purposes (Chapter 12) are void; there’s no scenario where they become valid. Similarly, a contract made by someone legally adjudicated insane is void. On the other hand, a voidable contract is valid until one party (the protected party, such as a minor or a fraud victim) chooses to void it. It’s enforceable if they agree, but they have the right to cancel. Examples: contracts induced by fraud, or with a minor, or under duress – these are voidable at the election of the wronged or protected party.

Ratification occurs when a party that could void a contract decides, instead, to accept it and be bound. For instance, a minor who turns 18 can ratify a contract (explicitly or by conduct like continuing to use a service) and then it’s fully binding, waiving their right to disaffirm. Similarly, a victim of fraud might ratify the contract after learning the truth (for example, by continuing to accept benefits or not challenging it) – then they lose the option to void later. Timing and knowledge are key: one can only ratify a voidable contract when they have full knowledge of the facts and, for minors, after obtaining capacity.